The Real Reason We Haven't Been Back To The Moon

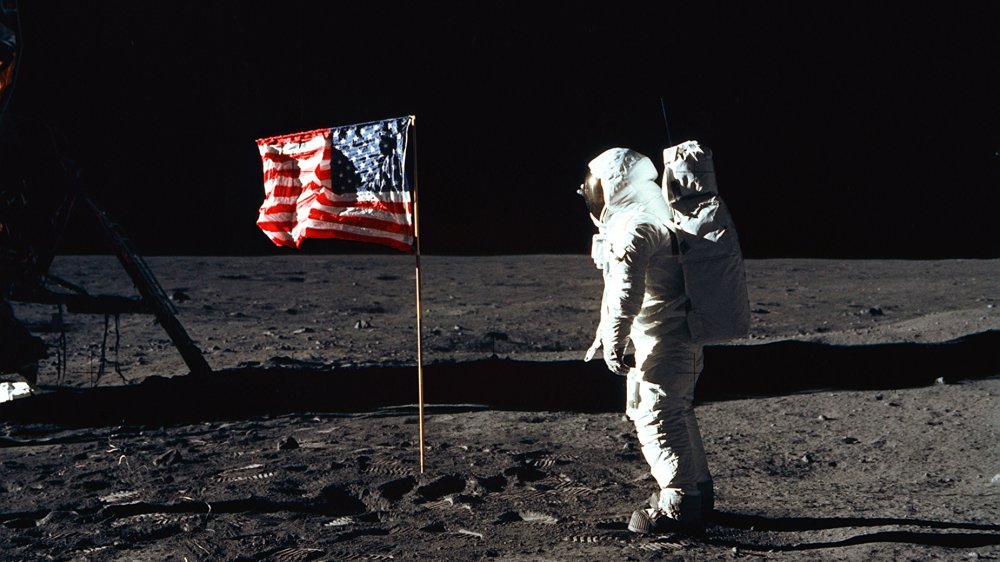

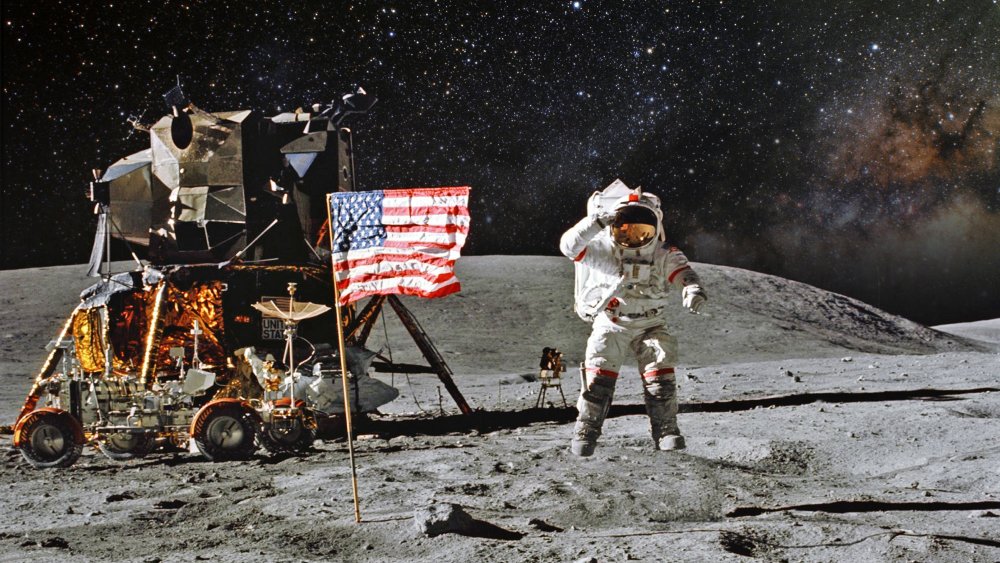

On July 20, 1969, one of the most momentous events in human history occurred: Men walked on the Moon. It was the culmination of more than a decade of scientific, engineering, and political work and represents one of our greatest achievements. Eventually the United States completed six Moon landings, bringing a total of 12 astronauts to the Moon's surface by 1972.

And then we stopped.

It will soon be five decades since a human being has walked on the Moon's surface. Contrary to countless science fiction stories, we don't have a Moon base. Contrary to a lot of optimistic opinions, we're not even very close to ever going back. Normally, the hardest part about getting from one place to another is the first time; after that, the logistical problems have been solved and the trip becomes easier and easier. For example, once Europeans figured out there was an enormous land mass between them and India, going to and from the Americas quickly became routine.

So how come that hasn't happened with the Moon? Although your first guesses are probably part of the explanation, there isn't just one real reason we haven't been back to the Moon. There's a whole matrix of reasons keeping us sadly Earth-bound.

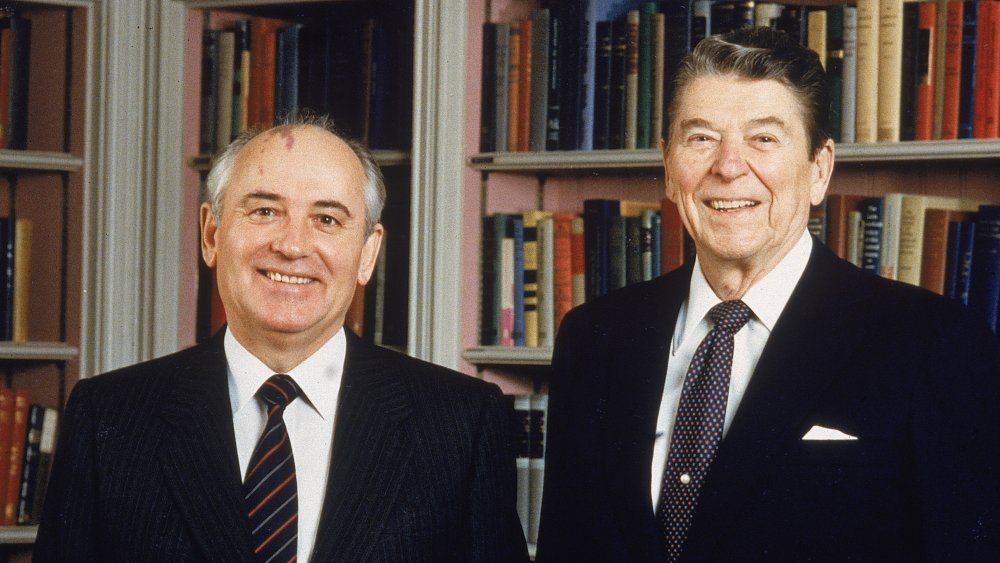

The Cold War ended

One of the key drivers of the USA's quest to land men on the Moon was a sense of competition with the Soviet Union. As Ars Technica reports, the Soviet Union poured money and expertise into their space program in the 1950s, and achieved several amazing fists. Sputnik was the first artificial satellite orbiting Earth in 1957, and in 1961 Soviet pilot Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to orbit the Earth. By the early 1960s, it seemed obvious that the Soviets were going to be the first nation to land someone on the Moon.

The Cold War was in full gear, and the potential technological and strategic advantages such a feat would give the Russians was a concern. President Kennedy said in 1962 "This is, whether we like it or not a race. Everything we do [in space] ought to be tied into getting to the Moon ahead of the Russians."

As noted by former NASA Chief Historian Roger Launius, the Space Race was really a proxy war between the United States and the Soviet Union. Instead of deploying tanks and troops on Earth, the two countries deployed scientists and engineers in an effort to claim the Moon as their own—if only symbolically. Those Cold War conditions no longer exist, and so far, no country has risen to the same rivalry with the USA as the Soviet Union had, removing a key reason we went to the Moon in the first place.

It's too politically risky

It took more than a decade to get us to the Moon the first time. It also took an incredible amount of money and effort, both mental and physical. And it could have gone wrong at any time—technology could have failed, astronauts could have died, or a new president could have simply canceled the project. The political risks were so high it's actually miraculous the project succeeded.

As Business Insider reports, those political risks have only gotten worse in the decades since our last visit to the Moon. Presidents have frequently suggested a return to the Moon, and NASA has come up with several plans to do so—but once the price tag shoots up and the challenges become clear, these plans are usually shifted to goals perceived as more practical.

That's the other problem: The benefits of going back to the Moon are largely theoretical. Scientific research is a key reason to go back—but there's no clear profit margin. A Moon base could be used as a refueling depot, but until there's a more practical reason to go to and from the Moon—or to use the Moon as a layover on our way somewhere else—the risks associated with such a project are frightening. Put simply, no politician wants to have their name associated with an expensive boondoggle, or a tragic disaster.

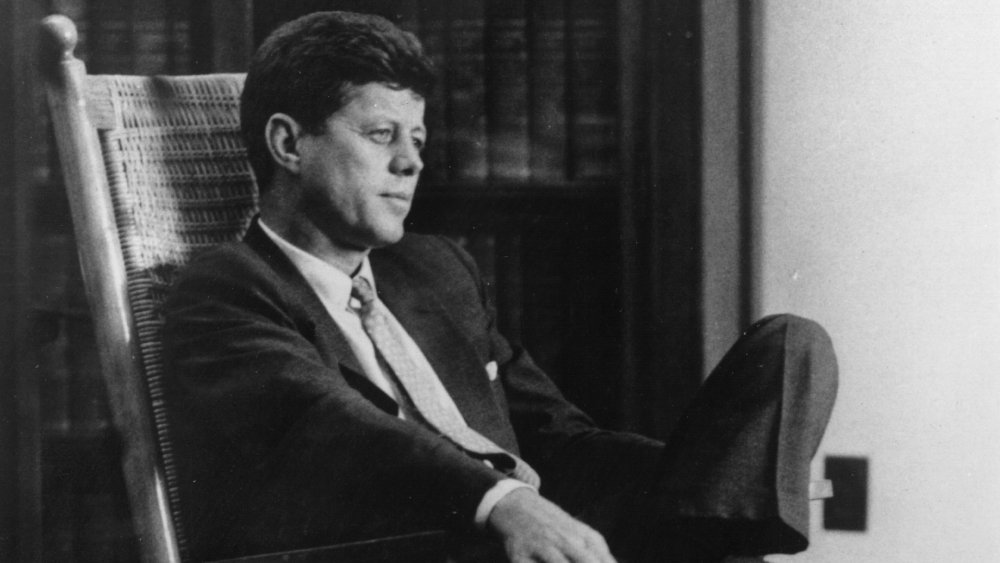

The original moon landing was a PR stunt

It's absolutely true that John F. Kennedy was the man who pushed for going to the Moon, citing the need to fight the Russians' efforts to dominate space. But the truth is a little less inspiring. Because part of the reason President Kennedy pushed so hard for the Space Program was his need for some good publicity after a series of political disasters had his administration reeling.

As CNET reports, Kennedy began his presidency convinced that a Moon landing would be far too expensive to seriously consider. Then he had a very bad, no good year in 1961. The Soviet Union made the USA look bad when they put Yuri Gagarin in orbit around the Earth. That made the USA look weak, and made the argument that we couldn't afford to go to the Moon look kind of silly.

Then Kennedy green-lit the Bay of Pigs Invasion. This was a disaster for Kennedy. It was so poorly organized and incompetently executed, it made Kennedy look really, really bad. It changed his attitude towards his military leaders and advisers, and it forced him to look for a way to change the conversation. Announcing a bold "Moonshot" mission was ideal. It made him look like a visionary leader and it made the USA look like a technological superpower. If you want us to go back to the Moon, we might need a new political disaster.

The moon landing wasn't designed for repetition

Landing on and strutting around the Moon in 1969 was an incredible feat. Sure, it cost a tremendous amount of money and effort, but you'd be forgiven for assuming that once we've achieved a goal like this, it must get easier to do.

Unfortunately, you're wrong—and that's one big reason we haven't been back since the end of the original Apollo Program in 1972. As noted by the MIT Technology Review, because the original Moon landing project was positioned as a "race" against the Soviets, the project wasn't designed for efficiency. Shortcuts were used wherever possible, and no one thought to build sustainable supply chains. The end result is a system where the equivalent of two or three jumbo jets' worth of technology and engineering is just burned up or thrown away, never to be used again.

In other words, the whole system of getting people to the Moon was never designed for repetition. It's actually amazing we ran 17 Apollo missions and got to the Moon six times using it. If we want to get serious about going back, we'll need to design a sustainable, efficient system for doing so. Don't hold your breath; in 2007 Google announced the X Prize, offering $20 million to the first non-governmental organization to complete a lunar landing. Since then only three crafts have landed on the Moon—all government projects, none crewed.

The original Apollo designs were barely safe

Since 1969 we've managed to put a total of twelve people on the Moon. That's incredible, but even more incredible is the fact that they all survived the trip. Put simply, getting to the Moon and back is incredibly dangerous, and the danger is exacerbated by the fact that Apollo craft design could be described as taking a "minimally-viable" approach to safety.

As Buzzfeed News reports, the frantic race to put men on the Moon led to a lot of corner-cutting in terms of the technology and engineering used. After the 1969 Moon landing, the sense of urgency that drove the project evaporated. We'd beaten the Soviet Union to the Moon, after all, and every subsequent Apollo mission seemed to underscore how little we got back out of these expensive and stress-inducing missions.

It all came to a head in 1970 when the Apollo 13 mission went horribly wrong. An explosion jettisoned the crew's oxygen supply and damaged the module, leading to a tense, frightening trip home in a crippled ship. While the astronauts returned safely, the incident underscored the fact that the Apollo spacecraft was, in the words of historian John Logsdon, being pushed "right up to the edge of its safe performance." Not long afterwards, President Nixon cut funding for the Moon landings and shifted NASA's focus to cheaper, safer projects: Skylab and the Space Shuttle.

We need better technology

Technology is always advancing, right? We managed to put together spacecraft that carried astronauts to the Moon and then got them home safe and sound in 1969. Surely the last five decades have seen some incredible advances in the technology needed for such a mission?

If you're talking about computers, the answer is yes. The computers on the Apollo lunar modules were incredibly basic compared to today's hardware. In fact, as Real Clear Science notes, the smartphone in your pocket is probably 100,000 times more powerful than the computer in the Apollo spacecraft. Heck, some calculators released in the 1980s were more powerful.

But computers are just part of the technology required to get people to and from the Moon—and their limited capabilities were by design, as they needed to be extremely efficient in order to use very little electricity. And as noted in Forbes, much of the hardware used in the Apollo missions remains state-of-the-art—and this technology was barely good enough to get us there and keep everyone alive back then. The lack of serious advances can be seen in how similar today's Space X launches are to the launches in the 1960s—not much has changed. And that's one huge barrier to going back to the Moon.

Presidents aren't patient

Legacy is always on politicians' minds. John F. Kennedy officially launched the mission to land on the Moon in 1962. By the time we actually accomplished it in 1969, he had been assassinated—but he would have been out of office even if he'd lived, thanks to term limits. Richard Nixon, who Kennedy had defeated in the 1960 election, was the man who got to bask in the publicity generated by the Moon landings.

That makes presidents hesitate. As Lifehacker notes, since it can take a decade—or more—to fund, design, build, and test something as complex as a Moon landing, any president that pushes for such a project is guaranteed to be out of office by the time it reaches fruition. In today's political climate where presidents are never not campaigning, that's intolerably long to wait. And incoming administrations—especially if they're of the opposing party—have a habit of canceling big projects put into motion by their predecessors precisely to deny them the credit.

In fact, Buzz Aldrin, the second man on the Moon, has argued pretty plainly that the only way we're getting back to the Moon is if both political parties in this country put aside their differences. "I believe it begins with a bi-partisan Congressional and Administration commitment to sustained leadership," the legendary astronaut said, and he's not wrong.

The Challenger and Columbia disasters

As Buzzfeed News notes, the Space Shuttle program was pushed forward in the 1970s because it would be cheaper than landing on the Moon—and safer. The Space Shuttle program might have been a step back from the incredible achievement of putting people on the Moon, but it kept humans in space and served an incredibly important purpose both in preserving the USA's position as a leader in space exploration and people's excitement about it.

When the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded on takeoff in 1986, it was a horrifying moment that chilled the entire nation. As Space notes, that event led to changes in how NASA worked and how the Space Shuttle program was used. It was scaled back, and some of the missions the Shuttle was performing were shifted back to older, more reliable technologies.

Then, in 2003, the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated when returning to Earth. As PBS reports, this second disaster had a much broader effect on the space program. President Bush and his administration question whether it was worth putting human lives in danger by putting them routinely into space. This new, more cautious attitude pretty much ended any chance of a serious effort to return to the Moon—such a mission suddenly seemed far too dangerous.

Making the moon pay is difficult

Like it or not, we're a capitalist society. Projects are pitched with a return on investment—and putting people on the Moon just doesn't offer any kind of profit. In fact, when you consider how much incredibly expensive technology winds up burning up and crashing into the ocean, never to be used again, it runs into negative numbers by a wide margin.

There are some possible ways the Moon could be made into a profit-making operation, which would attract investors and corporate money to the project. As noted by Space, the Moon is a rich source of helium-3, a rare—and finite—element that could one day be a tremendous source of power. And the Moon could also be set up as a stopover point for longer trips. For example, a manned mission to Mars could fly to the Moon, refuel, and have a much better chance of arriving safely on the Red Planet.

But for either of those scenarios to make sense, we'd need a permanent Moon base of some sort. According to Yahoo Finance, estimates on the cost to establish a "basic" sort of base run to the $100 billion range—and maintaining just four astronauts in such a base would cost $36 billion a year. And that's before setting up the equipment and infrastructure for mining or refueling operations. That means making any sort of profit is nearly impossible—and so enthusiasm for a return remains low.

New resources opening on Earth

One major reason that plans to return to the Moon have been put on hold is that the resources necessary for such a massive undertaking are needed much closer to home. In the Arctic, specifically.

As CNBC reports, climate change is quickly transforming one of the most inhospitable areas of the world, the Arctic Circle, into a rich source of new, resource-packed territory. It's estimated that oil and natural gas reserves worth as much as $35 trillion are waiting under the ice, and the USA is locked in a race with both Russia and China to secure as much of the area as possible. Much of the money and engineering brains that might be working towards a new moonshot are instead working on this problem instead.

The similarities between the challenge of building a base on the Moon and locking down the rights to the Arctic are so strong, in fact, that Wired reports that the race to control the Arctic is viewed as a dry run of sorts for the eventual race to control the Moon. There are already legal arguments forming that the way things are handled in the Arctic as it opens up should be a model for how disputes might be handled in the future on the Moon. But we won't get to the Moon until we sort out the much more pressing—and more local—issues here first.

The focus is on Mars

"Been there, done that" doesn't seem like it would be a viable political or scientific attitude, but it sums up the basic attitude of many when it comes to the Moon. In fact, many people in the government and in space-related agencies think we should be focusing on Mars as a priority.

As Scientific American reports, the House of Representatives' Committee on Science, Space, and Technology introduced a bill this year to make exploration of the red planet NASA's official stretch goal. Not only is Mars a much more valuable destination in terms of scientific research and expanding our understanding of the universe, it's also a goal that has captured the public's imagination.

That doesn't mean going back to the Moon is completely off the table, however. As The Atlantic reports, most experts agree that the only way we're going to get human beings to Mars reasonably safely is if we build a relay station of sorts on the Moon. Astronauts would travel from the Earth to the Moon, refuel and make other preparations, then launch from the Moon to Mars, simplifying the logistics of the trip. But that means that we're still not going back to the Moon until someone puts some serious money, talent, and other resources behind a trip to Mars.

The global pandemic is slowing things down

The global pandemic has blessed us with toilet paper shortages, mask requirements, and endless Zoom meetings. Now there's one more thing you can blame on the novel coronavirus: A lack of progress on going back to the Moon.

When NASA announced plans to get American astronauts back on the Moon by 2024, many thought it was overly optimistic—but even if the schedule slipped, it was an exciting development. As Reuters reports, the plan to go back to the Moon led to serious work on creating a next-generation rocket called the Space Launch System (SLS), along with a new crew module called the Orion. The program has hit some bumps—it's already $2 billion over budget—but it was scheduled to be tested for the first time this year.

But just like every other industry, the aerospace world has been hit by the global pandemic. NASA recently announced it would be forced to shut down two important facilities: The Michoud Assembly Facility and the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. The closures were necessary because employees there tested positive for the coronavirus. The shutdowns have had a big impact: NASA had to officially suspend the SLS program for the time being, dealing a serious blow to any chances of a return to the Moon.