The Untold Truth Of The Grand Ole Opry

While it's one of the most popular genres of music on the planet now, country music wasn't always such a big deal. In fact, a good amount of credit for its popularity and for Nashville, Tennessee, being forever associated with country music is due to the Grand Ole Opry, a live weekly radio show that's been on the air for nearly a century.

In the early days of radio, there wasn't a whole lot of programming just yet. Stations basically threw stuff at the wall to see what would stick, and the Opry was a surprise hit, soon being listened to by families all across America as they relaxed in front of the radio together.

Artists from Johnny Cash to Taylor Swift have gotten their big break on the Opry stage, and it remains one of the most popular radio programs in the country, even as radio has become a smaller part of the average American's life.

The Opry had humble beginnings

The Grand Ole Opry debuted on November 28, 1925, just a few short years into radio's life span as a commercial broadcasting endeavor, according to History. It was also one of the first shows broadcast by Nashville-based AM station WSM, which was founded just a month earlier in October 1925. Initially, the show didn't have any lofty goals of elevating country music. It was essentially meant to be a virtual barn dance, a popular pastime in rural areas all over America, not just the South.

In fact, the show's original name was "WSM Barn Dance", according to Mental Floss, a title meant to ape National Barn Dance, a popular show with a similar theme airing out of Chicago. It wasn't called the Grand Ole Opry until two years later, when early show announcer and eventual longtime producer George D. Hay dubbed it such while transitioning from an opera program WSM had been airing just before the show started. Yes, if you've ever wondered, it turns out "opry" is just a Southern colloquialism for the word "opera."

The show was a big hit right out of the gate, and it wasn't long before other stations began rebroadcasting the Opry across America. It soon became required Saturday-night listening, sort of like how people all had to tune in and watch TV shows at the same time or else they'd miss them. You know, back in the Dark Ages.

The Opry isn't just about country music

While it's tempting to assume that the Grand Ole Opry solely focuses on country music, that's not strictly the case. Throughout the decades, the Opry has also heavily featured country-adjacent genres like bluegrass, folk, Americana, and western music. Basically, if it was music anyone could make with simple instruments, the Grand Ole Opry was all about it.

Here's a thing you may not know about the show, though: It's not even all about music. The Opry has a long tradition of comedy performances and sketches between songs. This has even attracted people from outside of the country music world to appear on the Opry stage. For example, legendary comedian Carol Burnett once came on the show to trade quips with none other than Dolly Parton (who would later dabble in comedy herself) in a famous 1979 segment, according to Wide Open Country.

The Opry has even birthed some of its own comedy icons, such as Minnie Pearl (pictured above). A character created by Susan Ophelia Colley Cannon, Pearl was an exaggerated caricature of rural Southern culture, with a bizarre family life and little luck in her hunt for romance, according to Wide Open Country. The Minnie Pearl character ended up making it to lots of places other than the Opry, including numerous commercials, television performances, and even a very short-lived fried chicken franchise.

The Nashville sound

The Grand Ole Opry is a de facto institution in its hometown of Nashville, Tennessee. While the Opry has called a few different venues home, its most famous by far is Nashville's iconic Ryman Auditorium. It started life as a church called the Union Gospel Tabernacle, but the building's construction had such great acoustics that it eventually became used for all sorts of other events and changed into a full-time performance venue.

Since 1974, though, the show has been recorded in east Nashville at its own dedicated location, the Grand Ole Opry House, according to the Opry's own history. They didn't just stop there, either. The land surrounding the Opry House has been home to several other Opry-themed businesses as well. From the 1970s to the 1990s, a music-themed amusement park called Opryland USA operated there, as well as the associated (and still very popular) Opryland Hotel, meant to be a place for visiting musicians and tourists checking out the theme park to stay. After Opryland USA's closure, the land was repurposed to be a shopping mall known as Opry Mills.

In fact, during construction of Opry Mills in 1999, the Grand Ole Opry was unable to use the Opry House studio and, for three months, returned to the Ryman Auditorium for the first time in 25 years. This event was so popular that the Opry now returns to the Ryman three months out of every year for a limited engagement.

The station the Opry built

WSM was effectively a brand-spanking-new radio station when the Grand Ole Opry started. The Opry was WSM's first big hit show, and, as it happens, it's still broadcasting today, nearly a century later. Based out of Nashville and broadcasting at 650 khz, WSM-AM still exists. In fact, it's one of the few radio stations in the United States to have clear channel status, which means you can tune into it from a significant distance away.

Not only that, but it also has a sister station, called WSM-FM, on the FM band, which itself is one of the most popular country stations in America and was the first commercial FM radio station in America, according to WSM's own history. The station is rebroadcast all over the world, too, so it's likely you can pick up a signal wherever you are. Both WSMs are powerhouses in country music today. As for the Grand Ole Opry itself, you can find it in all sorts of places if you can't tune into WSM, even satellite and internet radio.

There's also a WSM television channel, WSMV, which is Nashville's NBC affiliate and has broadcast live from the Opry stage on many occasions. Basically, the Grand Ole Opry was directly responsible for one of the biggest broadcast franchises in Nashville and, arguably, in the U.S. itself.

Grand Ole Opry membership has its privileges

Being a featured performer on the Grand Ole Opry is one thing, but with enough appearances and solid performances, an Opry guest can be given one of the most prestigious honors a country musician can get: Grand Ole Opry membership. This gets you into a small club of musicians the Opry has decided to honor. This membership lasts until death, but performers are required to make a minimum number of appearances on the show per year as a trade-off, according to The Boot.

Think of it like a country music hall of fame (though there's also one of those, located in Nashville, too). Opry members are like the best of the best. They're the elite-diamond-club-premier-whatever status that lets you sit in the really fancy lounge at the airport. That's what being a member of the Grand Ole Opry is like. You can probably even put it on your business cards.

Looking through the list of current and past members is like a who's who of country, bluegrass, folk, and so on. Some of the more famous members include Roy Acuff, Patsy Cline, Garth Brooks, Blake Shelton, and both Johnny and June Carter Cash, just to name a few. Basically, if you're an iconic country musician, there's an excellent chance your name can be found in the membership roll of the Grand Ole Opry.

Some instruments used to be banned at the Opry

Early in the Grand Ole Opry's life, they took the idea of rural music extremely seriously, to the point that only certain instruments were even allowed to be featured on the show. Electric amps and guitars were forbidden for years until the 1940s, when this restriction began to relax after Ernest Tubb frequently played the show with one. Beforehand, all instruments had to be acoustic.

An even more strict ban came in the form of percussion and horns. These instruments were considered to be associated with blues and jazz music, not country, which traditionally only used a bass line for accompaniment at most, according to Drum Magazine. The electric guitar was also heavily associated with blues and jazz, but there came a point where that one was unavoidable. Drums remained discouraged until the 1970s, however.

Before the ban was lifted, a handful of artists throughout the decades did manage to sneak percussion onto the stage (or, more commonly, behind a curtain or offstage), and since the Grand Ole Opry is recorded live, the show's producers had no choice but to let it happen. One of the most famous instances of this came in 1944, when Bob Wills had a drum set ready to go just offstage and then had his bandmates push it onto the stage for a single song. The Opry management let Wills and his band finish the song, but they were never invited back.

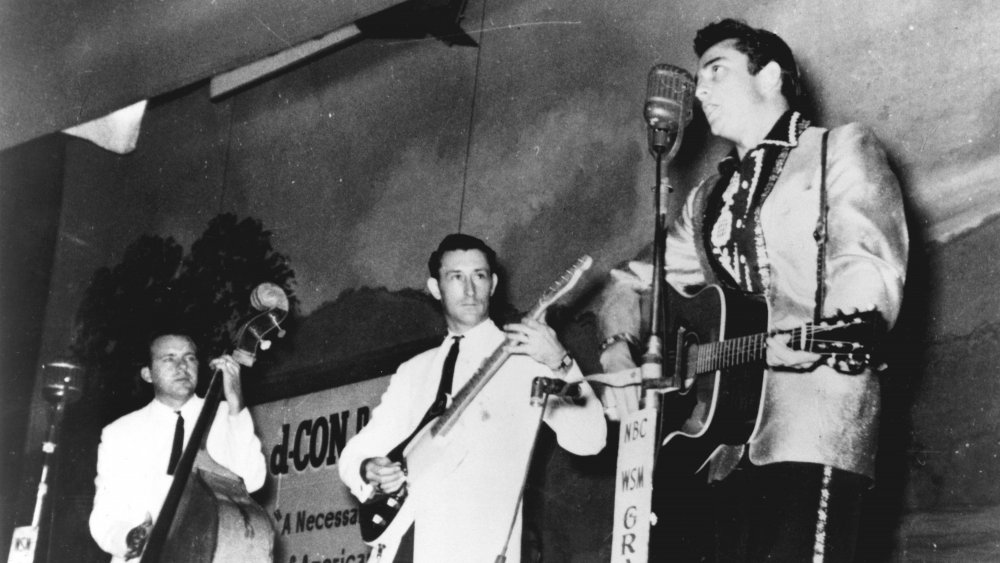

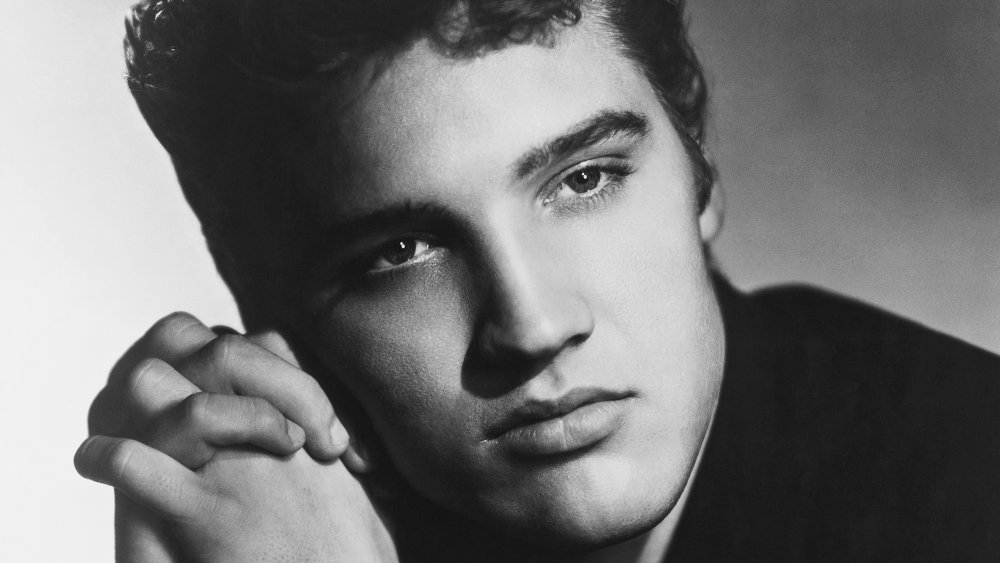

Mr. Presley plays the Opry

Not every country or country-adjacent artist has been warmly welcomed by the Grand Ole Opry, though. You might have heard of a small-time musician named Elvis Presley, who appeared on the Opry exactly once and then faded into obscurity forever. Or, at least, that's what Opry management seemed to assume would happen.

Elvis was a teenage truck driver from Memphis who scored a huge win by being invited to perform on the Grand Ole Opry stage. He traveled to Nashville with his guitar and played a relatively low-key version of the rock-tinged music that would make him a legend just a few years later. The crowd was politely receptive, but they weren't wild about it. Elvis' screaming young girls phase was still a few years away.

Opry management, however, was not nearly so kind, according to Offbeat Tennessee. They told Elvis that his musical style wasn't suitable for the Grand Ole Opry's hallowed stage. In fact, according to legend, they actually told him to go back to Memphis and return to driving a truck, because he'd never make it in the music industry. Elvis never came back to the Opry, but it turns out he did just fine. It's not clear if the Opry never invited him back or if Elvis turned them down on principle.

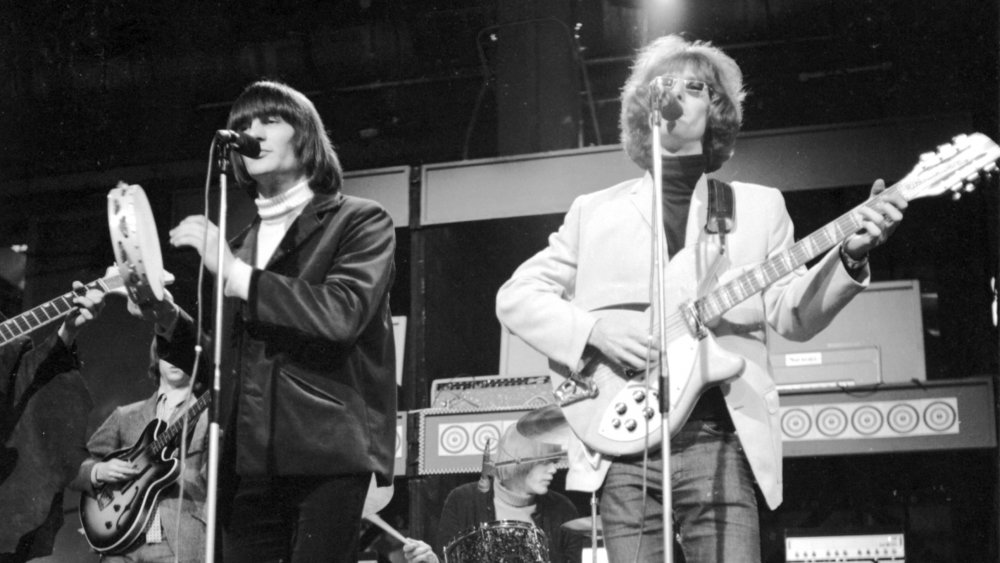

No hippies allowed

That wasn't the first time that the Grand Ole Opry turned away talented musicians, and it would certainly be far from the last time. In the 1960s, at the height of protests against the Vietnam War and the rise of the hippie movement, the Opry had an unspoken rule: No one with long hair was allowed to play the Ryman's stage. While this was meant to be a statement against anti-war protesters, it also had a lot to do with how they thought the show's audience might react to a long-haired musician.

After much consideration, though, Opry management invited folk rock band the Byrds to come play a show in support of their country album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, according to Rolling Stone. Given their status as crossover artists, the Opry knew it was taking a risk on the Byrds but went with it anyway. This turned out to be a complete disaster.

Immediately, the audience began booing and heckling the band solely for the length of their hair. The band, undeterred, played anyway. They were meant to play a cover of Merle Haggard's "Sing Me Back Home," but band member Gram Parsons decided to change things up and play one of the band's own songs, called "Hickory Wind", the performance of which Parsons dedicated to his grandmother. Changing songs without clearing it with Opry management was the final straw, according to Wide Open Country. The Byrds weren't allowed back on the Opry until 1989.

F-bombing onstage

Iconic rock 'n' roll pioneer Jerry Lee Lewis also got to play the Grand Ole Opry exactly once. While Lewis was most famous for his rock music, he had some country chops, too. Opry management invited Lewis to play the show in 1973 under two conditions: no profanity and no rock 'n' roll.

Jerry Lee Lewis, never one for following the rules, flagrantly broke both of these conditions, according to Rolling Stone. Immediately upon being introduced, Lewis described himself to the audience as a "rock and rollin', country-and-western, rhythm and blues-singin' motherf*cker," after which he played several rock songs, including his hits "Great Balls of Fire" and "Johnny B. Goode." Keep in mind that the Grand Ole Opry is always broadcast live, meaning that f-bomb went out to audiences all over the United States.

Lewis was allowed to finish his set, though he ignored his time restrictions and commercial breaks, playing for an unheard-of 40 minutes, further angering Opry management. He was forbidden from ever playing the Grand Ole Opry again. As of 2020, nearly 50 years after the incident, Jerry Lee Lewis has never been invited back to the Opry stage. At this point, since Lewis is over 80, it's highly unlikely that he ever will. Nothing's impossible, of course, but after that performance, it's also kind of understandable that the Opry might be reluctant to have him back.

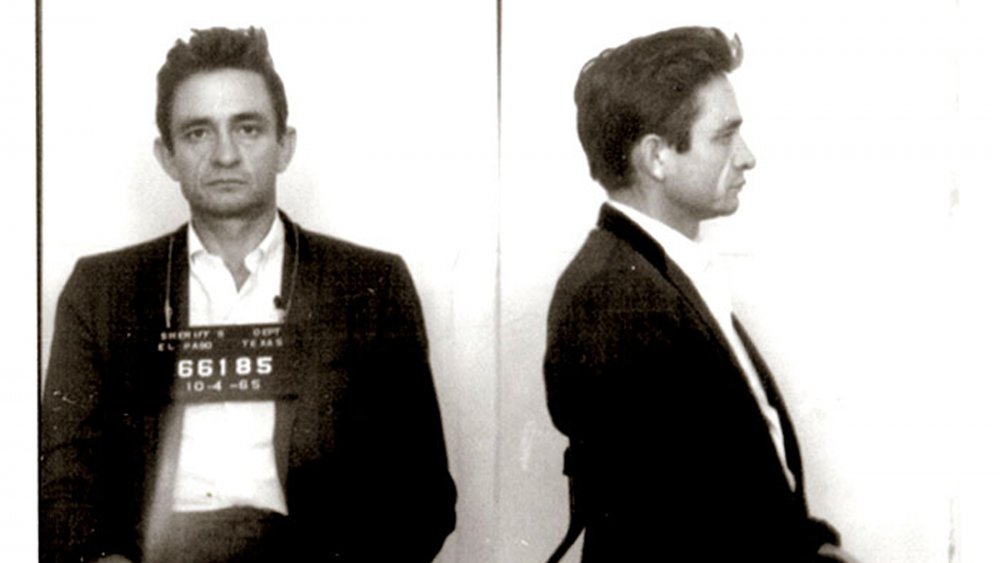

Johnny Cash's Walk the Line meltdown was real

Fans of the 2005 film Walk the Line starring Joaquin Phoenix as a young Johnny Cash might remember a scene where, in a fit of drunken anger, Cash smashes the stage lights at a show in Las Vegas before collapsing. This was actually based on a real incident, and it didn't happen in Vegas but on the Grand Ole Opry stage, according to The Boot.

In 1965, Cash played the Opry intoxicated and, taking a microphone stand, smashed out the footlights at the Ryman. Since he had been developing an outlaw country reputation for some time, this actually scored him some points in that regard, but the Grand Ole Opry's management was highly displeased. Cash was subsequently banned from the show, though he had been an Opry member since 1956. He had first met June Carter, whom he would later marry, backstage at the Opry, so it was already a major part of his life and career.

The ban didn't last, however. By 1968, Johnny Cash was back at the Opry and even hosted a few television specials there. He had cleaned up his act by this time, divorced his first wife, and proposed to June Carter the same year. While Cash would later fall back into alcohol and drug abuse, he behaved himself on the Opry stage going forward and maintained his status as a member until his death.

The 1,000-year flood that destroyed the Opry stage

In 2010, unprecedented amounts of rainfall hit Middle Tennessee, causing widespread flooding and damage, described as a 1,000-year flood. This flooding destroyed several Nashville landmarks, and one of those was the Grand Ole Opry House, situated on the Cumberland River, which quickly overflowed its banks in the torrential rains according to The Boot.

It's estimated that the Opry House ended up under around 10 feet of water, according to Wide Open Country, and its neighbor, the Opry Mills shopping mall, located on the same property as the Opry House, was so badly flooded that it was closed for nearly two years while it was renovated. The Opryland Hotel was completely evacuated of all guests. One of the most heartbreaking losses was the destruction of the Opry House's stage. One part of that historic stage did survive, though.

When the Opry House was originally built in 1974, a circle of wood cut from the original Ryman Auditorium stage, where the Opry had been played for over 30 years, was placed into the center of the Opry House stage. Amazingly, despite the floods that destroyed the newer stage, the circle of wood from the Ryman was able to be saved and restored. A new stage was built for the Opry House, and the Ryman's circle of wood was replaced at center stage once again.

The 2020 pandemic sent the audiences home

Throughout the Opry's lifespan, its broadcast shows were just one part of the performance each week. The Grand Ole Opry also allowed live audiences to attend the recording, with the Opry selling tickets to each of the show's performances. This did double duty as a source of revenue for the show and also attracted a regular stream of tourists to Nashville to watch a live recording of an Opry show.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 changed this, though. Due to social distancing ordinances and general safety requirements, for the first time in nearly a century, the Grand Ole Opry stopped having live audiences at their performances, according to Forbes. Musicians instead played to an empty theater, continuing the Opry's nearly century-long, uninterrupted streak (minus one episode that was cancelled after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis in 1968). While this was an understandable decision, it also left the Opry management without a significant portion of their regular income, which helps keep the lights on each week.

The Opry instead had to rely on advertisers for their entire revenue stream. Because this was a smaller source of income, though, the Grand Ole Opry had to struggle to keep its doors open for the first time in its nearly 100 years of existence, according to Fox Business. As of September 2020, this situation is still ongoing, and live audiences are still not allowed to attend the show's recordings each week.