The Tragic Story Of The Doctor Who Pioneered Hand-Washing

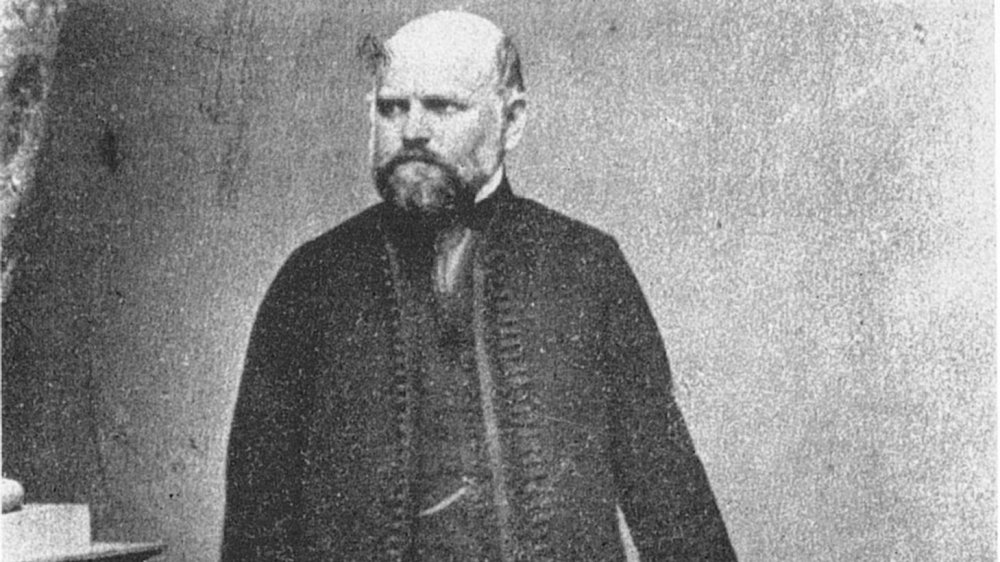

The Father of Hand Hygiene was largely misunderstood. During his lifetime, Ignaz Semmelweis was primarily known as an aggressive and eccentric man who maliciously attacked doctors based on unsound claims. After his death, it became clear that his theories about hygiene had validity. Yet, Semmelweis spent his life on a one-man crusade for which he was mocked, ridiculed, and eventually committed.

While Semmelweis's reasoning wasn't perfect, the changes he implemented consistently reduced maternal mortality rates wherever he was working. But his open irritation at his colleagues' refusal to get with the program led to workplace difficulties and whenever he was removed, the maternal mortality rate always jumped back up under his successor.

While Ignaz Semmelweis wasn't the first person to cite the importance of hand-washing, he correctly identified the link between doctors' hygiene and mortality rates, starting with mothers with puerperal fever. But during his lifetime, he faced major opposition and pushback to his groundbreaking theories. Had more people taken Semmelweis's research and science seriously, thousands of lives could've been saved. This is the tragic story of the doctor who pioneered hand-washing.

Semmelweis's early life

Ignaz Semmelweis, also known as Ignác Fülöp Semmelweis, was born on July 1, 1818 in the city of Buda, which later combined with the city of Pest to form Budapest, in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Born into a German and Jewish immigrant family, Semmelweis grew up in an affluent family that could afford to educate all eight of their children. He was the fifth child of Teresia Müller and Josef Semmelweis, both of whom worked as shopkeepers.

According to The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Semmelweis initially began studying law based on his father's advice, but after attending an anatomy class in 1838, he made the decision to transfer to study medicine. He completed his first degree at the University of Pest and completed his doctorate of medicine in 1844 at the University of Vienna.

While obstetrics wasn't Semmelweis's first choice for his specialty, according to PBS, his Hungarian background and Jewish origins relegated him towards the "less desirable division." In 1846, Semmelweis was appointed to work as an assistant in the maternity ward at the Vienna General Hospital.

A brief history of germ theory

While the notion that sickness can be caused by things that can't be seen has been around for thousands of years, it took a long time for this idea to meaningfully impact the habits of some. During the Middle Ages, Islam advanced various medical practices, especially using alcohol as an antiseptic. But up until the 19th century, a majority of Europe believed in the miasma theory of disease transmission.

According to "Death and miasma in Victorian London" by Stephen Halliday, the miasma theory held that disease was caused by inhaling bad air that had been corrupted by its exposure to something. However, while disease is able to travel by air, the miasma theory limited the understanding of the spread of infection to noticeably bad smells, which made it all the more difficult to convince people in 19th century Britain that the cholera outbreaks were being caused by polluted water.

Miasma theory prevailed around the world for hundreds of years. People in America shut the windows at night to prevent bad air from coming into the house. In China, medical schools were built to find a cure for miasma. While the theory of germs and microorganisms causing infections was sporadically acknowledged across Europe, it wouldn't be accepted widely until Louis Pasteur's silkworm experiment established a more expansive understanding of contagious diseases.

Semmelweis and the First and Second clinics

On July 1, 1846, Semmelweis began working at the obstetrics division of the Vienna General Hospital. The hospital had two obstetric divisions: The First, which was staffed by medical students and physicians, and the Second Division, which was staffed by midwives.

According to BMJ Journals, it was here that Semmelweis noticed that the post-delivery mortality rate at the First Division Clinic (13-18%) was drastically higher than the rate at the Second Division Clinic (2%). The difference in maternal mortality rate may have been even higher since during times of especially high mortality, many women were transferred to the general hospital and their deaths were incorporated into the statistics for the general hospital instead of the maternity hospital.

According to "Ignaz Phillip Semmelweis' studies of death in childbirth" by Irvine Loudon, almost all of the maternal deaths at the time were a result of puerperal fever, also known as childbed fever. Puerperal fever, now known to be caused primarily by the bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes, was blamed on a variety of different causes, including the cold, sewage, mists, or "vague putrid tendencies." But Semmelweis couldn't ignore the discrepancy between the two division's maternal mortality rates. Even his superior chalked it up to the ventilation system, but Semmelweis knew that there was something else going on.

Semmelweis's theory of cadaveric material

The death rate hadn't always been that high at that hospital. Before 1823, the maternal and newborn mortality rate at the Vienna General Hospital was closer to 1%. But then there was a policy change that mandated medical students and doctors practice autopsies on top of their other duties. Many even went straight from autopsies to delivery rooms, rarely washing their hands in between. Suddenly, maternal mortality rates jumped up to 7.5%.

Ignaz Semmelweis noticed that midwives at the Second Division weren't required to perform autopsies and, as a result, this division didn't suffer from the staggeringly high mortality rates. According to Loudon, the midwives at the Second Division also didn't perform gynecological exams as often on pregnant women, which also decreased the experienced exposure.

According to the Journal of the Turkish-German Gynecological Association, Semmelweis proposed that the transference of "cadaverous particles" from dead bodies were responsible for the increased mortality rates in the First Division Clinic.

Semmelweis's certainty grew after his friend Jakob Kolletschka died in 1847. Kolletschka had been conducting an autopsy on a woman who'd died of puerperal fever when he'd gotten cut by a scalpel. He died shortly of puerperal fever and his autopsy revealed a massive infection. Semmelweis realized that the interaction with cadavers was consistent with puerperal infections and that women who'd claimed that doctors were "harbingers of death" were possibly onto something.

Semmelweis drops the mortality rate

While Ignaz Semmelweis himself didn't suggest that germs were the culprits behind infections, his description of cadaverous particles bears as close a resemblance as possible. Since he didn't know exactly what the cadaverous particles were, Semmelweis also adhered to the logic of the miasma theory.

According to HHS Author Manuscripts, Semmelweis noticed that when doctors examined women in labor, even if they washed with soap and water, the smell of cadavers lingered on their hands. In response to this and in accordance with the logic of miasma, he instituted a rule that medical students and doctors were required to wash their hands in a chlorinated lime solution, which was best at removing the smell of dead bodies from their hands.

Semmelweis required that anyone entering the labor ward was required to disinfect their hands in this manner. Within three months, from June to August 1847, the change in death rates was dramatic. Maternal mortality in the First Division Clinic fell to 1.8%, similar to the rates at the Second Division Clinic. When death rates spiked again in October and November, Semmelweis began requiring attendees to wash their hands in between examining individual patients in addition to when they first entered the ward. By 1848, the death rates at the First Division Clinic had fallen to 1.27%, even less than the rates at the Second Division Clinic (1.33%).

Semmelweis's theory spreads

After confirming the effects of Semmelweis's theory of disinfection, Semmelweis and some of his colleagues wrote to various maternity clinics urging them to adopt a policy of hand-washing. Semmelweis didn't initially publish his experiment, although the results were publicized in an editorial in December 1847 in the Journal of the Medical Society of Vienna.

Semmelweis and his colleagues reached out directly to heads of maternity clinics across Europe, inviting their comments. Unfortunately, few of the responses were positive. According to PBS, many doctors resented the suggestion that they might be the cause of their patients' deaths. Semmelweis was also not the first to make this suggestion, having been preceded by obstetrician Alexander Gordon of Aberdeen in 1795 and anatomist Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1843. But these theories weren't widely accepted and despite Semmelweis's successful experiment at the Vienna General Hospital, without published proof of experimentation and exploration, doctors refused to accept the validity of his findings.

Semmelweis's lecture was published in various medical journals, such as The Lancet, but since Semmelweis wasn't directly communicating his theories, it was frequently misrepresented and misinterpreted as a result.

According to BMJ Journals, even some of Semmelweis's colleagues tried to purposefully sabotage his implementation of hand-washing. But despite the resistance, Semmelweis stuck to his theory and maligned doctors who didn't subscribe to it as murderers.

Semmelweis returns to Hungary

Semmelweis's post at the Vienna General Hospital was a two-year contract and his supervisor, Johann Klein, decided not to extend Semmelweis's contract. According to "Ignaz Semmelweis, the Savior of Mothers" by Miklós Kásler, Klein had been the one to introduce the practice of post-mortem autopsies and was likely irritated by Semmelweis's efforts. Klein considered puerperal fever to be unpreventable and thought that while the statistics of childbed mortality were unpleasant, they were unavoidable.

According to HHS Author Manuscripts, after Semmelweis's contract wasn't renewed, he returned to Budapest and took on a non-paying position as the Head of Obstetrics and Gynecology at St. Rókus Hospital. While there, he tasked himself with reducing maternal mortality and instituted the practice of chlorinated hand-washing.

His efforts weren't for naught. During his six years at St. Rókus Hospital from 1851 to 1857, the maternal mortality rate was 0.85%. In 1857, Semmelweis also married Maria Weidenhoffer, with whom he had five children.

During the same time period, the maternal mortality rates in Prague and Vienna from childbed fever were upwards of 10% to 15%. In 1855, Semmelweis was also appointed Professor of Theoretical and Practical Midwifery at the University of Pest. He instituted the practice of disinfection there as well and was able to keep the rate of maternal mortality below 1%.

Reception and criticism of hand-washing

Overall, Semmelweis's theory was widely rejected. According to Forbes, many doctors claimed that "doctors are gentlemen and a gentleman's hands are clean." The job of a physician was considered to be "divinely blessed," so doctors considered it unfathomable that they might be responsible for sickness.

Many also thought that washing hands in between every single patient would simply take too much time. Plus, in order to allow for this, entire hospitals would have to be built so that running water and sinks could be easily accessible. All-in-all, few were willing to accept the validity of Semmelweis's findings.

Many refused to accept their responsibility and insisted that the condition arose within the pregnant women themselves. Ede Flórián Birly, professor of obstetrics at the University of Pest, thought that puerperal fever occurred as a result of an unclean bowel. Other doctors thought that childbed fever occurred because mothers were embarrassed about being examined by doctors who were men. Per HHS Author Manuscripts, Semmelweis's contemporaries believed that there were upwards of 30 different causes of childbed fever.

Although, according to "Ignaz Semmelweis, the Savior of Mothers" by Miklós Kásler, some obstetricians such as Gustav Adolf Michaelis introduced Semmelweis's methods and found that they had the same drop in mortality. But the discovery that childbed fever was so easily preventable sent Michaelis into a depression at the thought of how many women had unnecessarily succumbed and he killed himself in 1848.

Semmelweis officially publishes his research

In 1857, Semmelweis finally began publishing his own findings. As noted by HHS Author Manuscripts, Semmelweis was encouraged by Lajos Markusovszky and published his findings in Markusovszky's journal Hungarian Medical Weekly. Semmelweis responded directly to the English "contagionists," who claimed that Semmelweis was saying nothing new, and reiterated his belief that puerperal fever was caused by "decaying organic matter."

In 1861, Semmelweis finally consolidated his ideas and published the book "The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever." In this text, Semmelweis formally laid out his implementation of chlorinated hand-washing along with its rate of success and his theory of cadaveric material. He also responded directly to his opponents and their criticisms.

This text also received negative reviews, which prompted Semmelweis to lash out through a series of open letters in 1861 and 1862. Per the Universitätsbibliothek Medizinische Universität Wien, Semmelweis had no patience for doctors who refused to accept responsibility for their actions and denounced obstetricians who rejected him as "irresponsible murderers or ignoramuses." Unfortunately, this did little to further his case.

In his text, Semmelweis also lamented the rejection of his theories, noting that in 1854 alone, "in Vienna, the birthplace of my theory, 400 maternity patients died from childbed fever. In published medical works, my teachings are either ignored or attacked."

Breaking down from a lack of support

Semmelweis was not only ridiculed by colleagues but by family and friends as well. Despite the resistance, Semmelweis refused to abandon his crusade and rarely talked of anything other than childbed fever.

According to the Journal of Turkish-German Gynecological Association, in 1861 Semmelweis began suffering from "various nervous complaints." He reportedly began to experience severe depression and was noted to be excessively absentminded. Many considered his behavior to be "irrational, odd, and inappropriate." While many have tried to attribute Semmelweis's condition to Alzheimer's, syphilis, or dementia, it's possible that Semmelweis was merely suffering from emotional stress that was exacerbated by the dismissal and mockery of his theories.

Ultimately, Semmelweis had little patience for anyone who disagreed with his theory and his behavior started to become "irritating and embarrassing." Semmelweis continued to bitterly attack doctors and critics, but his spirit was breaking. By 1865, he was drinking heavily. According to Past Medical History, he also started frequenting sex workers and spending time away from his family. In response to his behavior, Semmelweis's family decided that it would be best to remove Semmelweis from public life.

Dying in a mental hospital

Ignaz Semmelweis's colleagues and wife thought that he was becoming too much of an embarrassment and conspired to have him committed. In 1865, they were able to lure Semmelweis into a mental hospital. According to "Psychology of Security" by Stefan Schumacher, after János Balassa, a prominent surgeon, referred Semmelweis to an institution, dermatologist Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra lured him to the Landes-Irren-Anstalt in der Lazarettgasse under the pretense of visiting the new institution.

Although Semmelweis quickly figured out what was going on and tried to escape, he was severely beaten by the orderlies and put into a straitjacket. According to HHS Author Manuscripts, it was likely during this beating, although it may have been during subsequent beatings, that Semmelweis received a fatal blow. One of his injuries became infected, and within two weeks of being admitted into the mental hospital, Semmelweis died of generalized sepsis on August 13, 1865.

According to Leaps in the Dark by John Waller, the fact that "Semmelweis was ill-treated despite his social standing, strongly suggests that his death was welcomed, if not prearranged." Semmelweis's death is also tragic in that Semmelweis died of the very type of blood infection that he spent most of his life fighting to prevent.

Semmelweis's legacy of hand-washing

After Ignaz Semmelweis died, János Diescher replaced him at the Pest University maternity clinic. Diescher had never been trained in obstetrics and it was quickly apparent how little he abided by Semmelweis's theory. After Diescher took over, maternal mortality rates at the Pest maternity clinic, which had been consistently 1% under Semmelweis, jumped to 6%. But there were no protests and no inquiries among the physicians.

Over the next twenty years, Louis Pasteur expanded germ theory, Joseph Lister elaborated on antiseptics in surgery, and in 1876, Robert Koch officially linked bacteria to infection for the first time. Per Miklós Kásler, despite the fact that Semmelweis attributed puerperal fever to "decaying matter" rather than "bacterium," his conclusions on antisepsis and asepsis remained entirely correct.

Unfortunately, according to PBS, during his lifetime Semmelweis was considered an angry, unstable man to be pushed out of the medical industry at worst and derided as an irritating eccentric at best. By the end of the 19th century, many countries expressed their regrets at the treatment of Semmelweis, but by that point, countless lives had been sacrificed by his opposition. In 1897, the Congress of the German Gynaecological Society Zweifel declared that Semmelweis's discovery ushered in a new era in medicine. But more than 100 years later, physician adherence to hand-washing only averages about 57%.