The Untold Truth Of CBGB

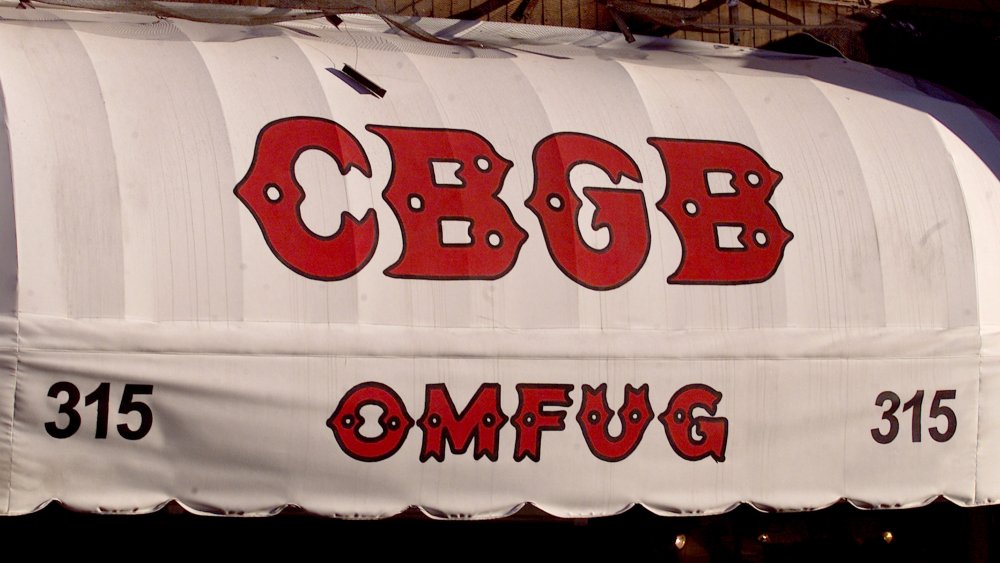

It's impossible to predict cultural touchstones. In 1973, the Bowery in New York City was a neighborhood in the midst of a lengthy decline. Blasted by poverty and crime, it wasn't a place that attracted tourists, and it was probably the last spot you'd suspect to see music history being made. And 315 Bowery was an even less likely spot: The former site of a rowdy biker bar was small, dark, and in poor repair even then.

And yet when Hilly Kristal shuttered his previous business, Hilly's on the Bowery, and re-christened it CBGB, it turned out to be the final ingredient in what would become one of the most important events in modern music. CBGB was the diviest of dive bars, but a magical combination of factors conspired to make it a legendary venue, a place where some of the most famous musicians of the past half-century debuted, and where some of the most legendary live performances of all time occurred. For more than 30 years, CBGB was shorthand for a cutting-edge music scene that was unpredictable, a little dangerous, and almost certainly unhygienic.

That also made the club emblematic of New York City itself. As the city changed and cleaned itself up, the club struggled to fit in with a more sanitary, less rowdy neighborhood. We'll probably never see the likes of CBGB again — so here's the untold truth of CBGB.

CBGB's founder was an old pro

By the time Hilly Kristal opened CBGB, he'd been a fixture in the New York City music and restaurant scene for decades. According to Village Preservation, Kristal was born in New Jersey, he went to Settlement Music School in Philadelphia, served in the Marine Corps, and then worked as a professional singer in New York City.

Hilly Kristal's singing career never quite took off, so he pivoted and began managing the legendary club Village Vanguard, booking some of the biggest names in jazz, like Miles Davis or John Coltrane. In 1966, Kristal opened his own restaurant, Hilly's, in the Village. Hilly's was about as far from the grimy punk scene that would define CBGB as you could get. It served French-style cuisine and booked musical acts like Bette Midler, with a focus on standards and show tunes. As the New York Times notes, Kristal was a fan of a broad range of music, especially folk music; he kept a guitar near his desk at all times.

According to The Bowery Boys, Kristal opened a new bar at 315 Bowery in 1969, calling it Hilly's on the Bowery. It was intended to be a spin-off of Hilly's, with the same vibe, but its main clientele were bikers, making for a rowdy place. That business struggled for years, and in 1972, Kristal decided to shut it down and relaunch. By the time he came up with CBGB, Kristal was an old hand in the restaurant and bar business.

Hilly Kristal had no idea he was launching a legend

When Kristal re-launched his struggling bar at 315 Bowery in New York City in 1972, he wanted to create a music venue that catered to the sort of artists he enjoyed. As Hilly Kristal himself makes clear, the name CBGB stood for Country, Bluegrass, and Blues.

According to Abandoned Spaces, in 1973 two locals, Bill Page and Rusty McKenna, persuaded Kristal to let them start booking local musical acts. The music scene in New York was evolving and there weren't many venues available for the acts that would eventually be known as Punk and New Wave. As The New York Times reports, the legendary musician (and CBGB regular) Patti Smith said, "There was no real venue in 1973 for people like us. We didn't fit into the cabarets or the folk clubs."

The acts that Page and McKenna brought in didn't match Hilly's initial CBGB vision. In fact, as Fuse reports, one of the earliest acts to play the venue, Television, actually had to lie to Kristal and claim they played some country music in order to get the gig. According to The Advocate he eventually added "OMFUG" to the bar's name, which stood for "Other Music for Uplifting Gourmandizers." That "other music" would come to define the spot as the launching pad for punk rock in the 1970s.

Hilly Kristal had two rules

CBGB quickly became an important part of New York's underground music scene. This was due to a number of factors, but one of the main reasons was simple: Hilly Kristal was kind of cheap. In fact, Kristal himself admits that the venue didn't initially guarantee that bands would get paid — though he gave them most of the door money to cover their expenses.

As Village Preservation reports, Kristal had two basic rules for the bands that were booked to play CBGB. The first was that they had to load and unload their own equipment. Kristal didn't employ anyone to do that for the bands, and he wasn't about to do it himself. The second was that the bands could only play original music — no cover songs.

While some people have painted the "no covers" rule as a dedication to originality and a keystone to punk's development as a musical form, Kristal's son Dana makes it clear in this interview with Tiny Mix Tapes that it was all about money: Kristal didn't want to pay American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) fees. These fees get charged any time a copyrighted song is played in a venue, and they can be quite expensive. According to Consequence of Sound, some bands managed to get a cover or two in under Hilly Kristal's nose, but by and large, the no covers rule held.

CBGB became a talent incubator

Hilly Kristal's requirement that bands act as their own roadies and only play original music — no covers — may have been inspired by a desire to keep his costs low, but it made CBGB fertile ground for new music.

As Ultimate Classic Rock notes, in early 1970s New York City it was difficult for bands to find venues that would not only book unknown musicians but also allow them to play original music. When CBGB offered to do both, it removed many of the barriers that kept hungry young musicians from getting the gigs that were crucial to their musical development and building a fan base. As uDiscover Music reports, legendary bands Television and The Ramones were some of the first groups to play CBGBs — and they had no following and wonky equipment that sometimes didn't work. But Kristal noted that these bands attracted other bands who needed a stage where they could get their music into the world.

Being that venue where bands could get their start soon meant that CBGB hosted some legendary debuts. As Diffuser notes, aside from Television and The Ramones, bands like The Beastie Boys, Patti Smith, Blondie, and The Talking Heads graced the tiny stage at CBGB long before they had record deals or were household names.

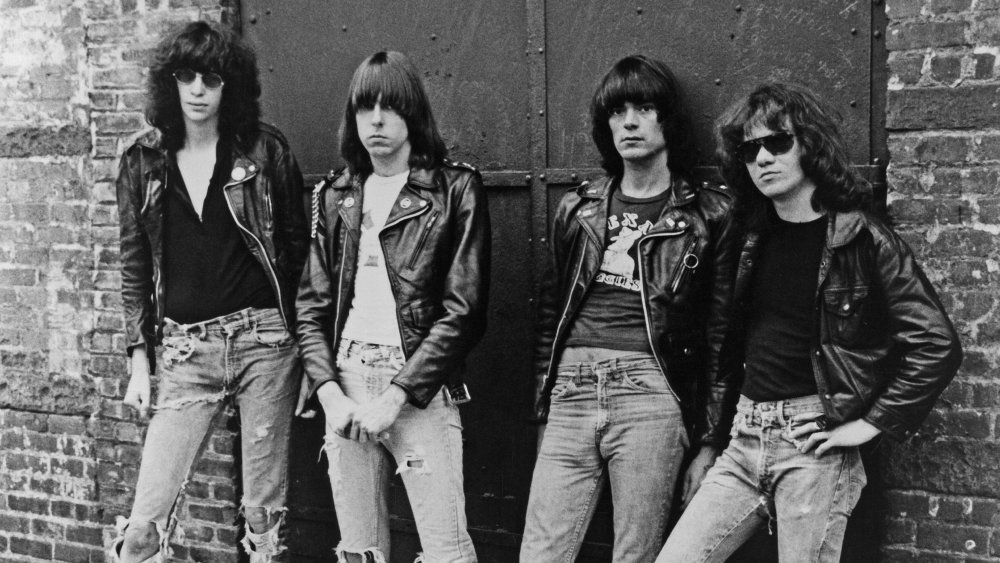

People at CBGB thought The Ramones were a prank

Of all the famous bands that played CBGB in its heyday, few are as iconic as The Ramones. As uDiscover Music notes, the seminal punk rock band began a residency at CBGBs in 1974, solidifying the bar's punk rock status. Over the years, The Ramones and CBGB became inextricably linked to each other and the punk rock scene, but when the band took the stage for the first time, no one knew quite what to make of them.

As Diffuser reports, when The Ramones played their first gig at CBGB, they ripped through their entire set in exactly 12 minutes. Their set was so fast and so loud, many in the audience thought it had to be a prank of some sort — or that the band had mental problems of some kind. At other gigs, the band reported tore through 20 songs in just 17 minutes.

This was intentional. In the 1970s, rock music had gotten progressive and theatrical, with songs often topping 10 minutes or more. As BlastEcho notes, the average song length on The Ramones' debut album is around two minutes, and over the course of their entire career, the average song length is just 2 minutes and thirty-seven seconds.

In August 1974, however, no one was ready for punk rock yet. But it worked: The Ramones went on to play CBGB 70 more times in 1974 alone, and both band and bar went on to become icons.

The bathroom at CBGB was legendary

There aren't many public restrooms that get immortalized in museums. While you might not be shocked to learn that the bathroom at a grimy club on the Bowery in New York City circa 1975 would be less than pristine, the conditions found in CBGB's bathroom were legendarily horrifying.

According to The New York Times, the bathroom at CBGB was used freely by both genders, who used it for both its intended purpose and for other, sometimes illicit or illegal, activities. Aside from its general griminess (David Byrne of The Talking Heads once described the bathroom as "legendarily nasty,") what made the bathroom iconic enough to be re-created as part of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was the accumulated graffiti. Bands would scrawl their names on the walls, and CBGB's owner Hilly Kristal just left the markings there. Slowly, the bathroom became an iconic spot in punk rock history.

Still, as this video of the bathroom shot just before the club closed down shows, it wasn't exactly a clean bathroom. As Gothamist reports, the fixtures that once graced the bathroom at CBGB are still out there and were used to dress the set of the 2013 film CBGB. This means that whatever had accumulated on those fixtures over the years is still out there too.

CBGB offered infamous food to its patrons

When you think of CBGB, you think of legendary music, a specific time in New York City, and a neighborhood that was legendarily rowdy and dilapidated. What you probably don't think about is lunch.

But as amNewYork points out, when CBGB first opened it actually had a working kitchen and offered food to its patrons. The kitchen was converted into a dressing room a few years later, but in the beginning, CBGB offered a small menu that included hamburgers and Kristal's soon-to-be-infamous chili. And that chili has become a bit of a legend in itself — for all the wrong reasons.

As The Advocate makes clear, health code was not exactly at the forefront of Kristal's mind as he cooked. The chili would often contain cigarette ash, and rats ran amok in the kitchen, almost guaranteeing animal droppings and other horrifying stuff made its way into the chili, too.

Worse, rumors swirled that the bands and patrons would often sneak into the kitchen and add various unsavory things to the chili. Regulars often reacted in horror when newcomers admitted they'd consumed some. Combined with the grimy conditions, it probably seemed wiser to get rid of the kitchen altogether rather than risk an epic case of food poisoning.

CBGB crowds were often small

As often happens with legends, the more time that goes by, the more people claim to have been there. When the heyday of CBGB is depicted in film and television it usually shows a packed house, a huge crowd fully aware that they are witnessing musical history.

The truth was a little different. As uDiscover Music writes, the first bands to hit CBGB's stage on a regular basis didn't have any sort of following. Groups like Television and The Ramones weren't famous at all when they played the club, and often shows were only sparsely attended. As The New York Daily News writes, in the early years the audience at CBGB was a very small group of local regulars about 200 strong who attended most of the shows.

That means there's a lot of revisionist history. For example, the gig The Police played at CBGB in 1978 is sometimes portrayed as a seminal moment in the club's history. But as Marc Campbell writes at Dangerous Minds, the bar was half empty the night they played, and there was no sense among the patrons that they were watching history being made. After all, most of the bands that played CBGB never broke out and became legends. For every night that has gone down in history, there were dozens that were just another night out listening to live music.

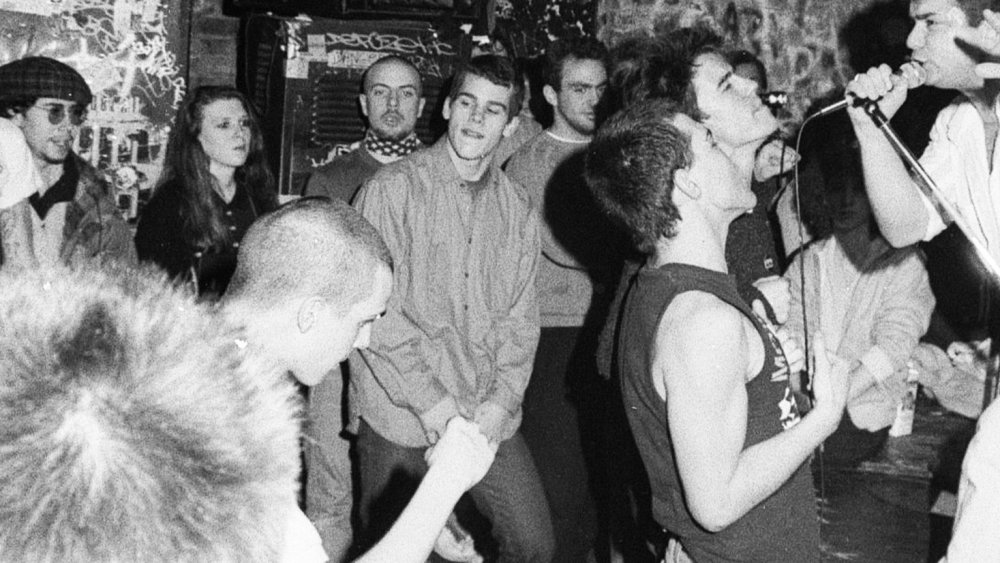

CBGB got dangerous

CBGB launched in 1973. By the 1980s, New York City and the underground music scene it incubated had changed a great deal. Bands like Blondie and The Ramones had gone mainstream as the local music scene mutated and evolved.

But CBGB did a remarkable job of evolving right along with it. As Consequence of Sound notes, owner Hilly Kristal established "hardcore matinees" to showcase the new wave of hardcore punk bands that were coming up, like Agnostic Front or the Cro-Mags. These matinees — which happened at night despite the name — were instrumental in popularizing this new, more aggressive brand of punk rock. These new bands made The Ramones seem quaint.

One consequence of this new scene was that the crowds became more violent, and CBGB garnered a reputation as a dangerous place to attend a show. In fact, Kristal temporarily stopped booking hardcore punk acts in 1990 because of all the trouble their fans were causing at the club. In The Village Voice, musician John Porcelly recounts blatant drug use in the bathrooms and an incident where a man had a bottle smashed over his head, and Sotheby's reports a story from the bar's former manager, Drew Bushong, about being stabbed in the neck by an unruly patron.

It should be noted that there's an alternative theory as to why Kristal tried to ban hardcore acts: He didn't think their fans drank as much as other crowds.

A rent dispute finally shut CBGB down

When Hilly Kristal opened Hilly's on the Bowery (the bar that would evolve into CBGB) in 1969, the neighborhood was a pretty bad one, and rents were very cheap. Over the years, New York City began to gentrify, and even the Bowery started to move up in the world. By 2005, the monthly rent for CBGB's legendary space was $19,000. But as The New York Times notes, even that sizable number didn't represent market value — as Kristal discovered when he was sued for back rent in the amount of $90,000, representing several automatic rent increases in the lease that he'd ignored.

Lawsuits flew between Kristal and the landlord. In 2006, when the lease expired, CBGB was asked to cough up $41,000 a month to stay at 315 Bowery. After more legal wrangling, a deal was struck that allowed CBGB to remain in place for a few months while they sought a new location. While Kristal apparently began looking for a new space, he passed away just a few months later, dying of lung cancer in 2007.

The New York Times reported on the last show at CBGB on October 15, 2006. The show, which was simulcast on satellite radio, featured the legendary Patti Smith, bassist Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Richard Hell of Television, one of the first bands to be featured at the bar.

Hilly Kristal turned out to be a millionaire

Although CBGB always had an aura of punk poverty about it, and Hilly Kristal always seemed to be barely surviving, according to The Village Voice he left an estate valued at $3.7 million. The discovery was shocking because shortly before his death, he'd convinced his wife, Karen, to sign over the ownership of the corporation that operated CBGB to him. According to The New York Times, Kristal then sold the corporation's assets and trademarks for $3.5 million.

The whole operation had been in Karen Kristal's name since 1973, despite the fact that the couple was already divorced, because Kristal had a bad record with bankruptcies. Karen Kristal also worked at the bar for years.

Kristal's will left his son some money in a trust, named his daughter Lisa his executor and left her all his assets — and left his wife nothing. Karen Kristal sued, claiming she hadn't known what she was signing. The suit got ugly. According to The Village Voice, Lisa Kristal Burgman eventually threatened to have a guardianship declared over her mother, which forced them to settle the suit. Reportedly Karen Kristal and her son Dana got some of the CBGB assets, and Lisa got everything else.

The CBGB brand lives on

There was once a time when owning a CBGB T-shirt was a badge of honor among music fans because the only place you could buy one was at the bar (or the boutique that existed for a while next door at 313 Bowery). Ironically, it's much easier to get one now that the bar is closed (the iconic location has been transformed into a John Varvatos clothing store) because the brand lives on as a clothing line and (weirdly) a restaurant chain.

As Vice hilariously notes, anyone can buy a CBGB T-shirt now, which kind of ruins the cool factor of owning one. You can buy CBGB clothing at Walmart, and Alternative Press Magazine notes that Dr. Martens, the shoe company embraced by underground folks everywhere, recently released a special CBGB-branded shoe. In other words, the corporate interests that now own the iconic CBGB name are wasting no time exploiting it.

The worst bit of legacy-ruining business, however, is probably the restaurants. As Vice reports, CBGB LAB (which stand for 'lounge and bar') opened at— of all places — Newark Airport in 2016. In other words, a club that was known for being filthy and offering perhaps the worst chili ever known to man has been rebranded as an airport restaurant. In New Jersey. There's nothing punk rock about that at all.