The Tragic Story Of The Colfax Massacre

Racial tensions have been — and still are — a pretty massive problem in American society. Looking back in time just gives you a better picture of this really bloody and violent history, filled with massacres, riots, and far more.

The number of violent race-related incidents in U.S. history is quite high, and while some of them are well-remembered for the effects they had, the same can't be said for all of them. Some have been just about forgotten to most people, and even in this time where people are becoming more aware of just what and who we memorialize (Confederate statues, for example), things do go under the radar.

The Colfax Massacre is one of those events that's just sort of gone without recognition, despite being one of the bloodiest events of the Reconstruction era — and, in a way, bringing about its end while ushering in the segregation of the 20th century. It's a rather dark part of American history you might not have heard of before, so here's the full story.

The Civil War and Reconstruction

So, let's get some historical context for this, because the Colfax Massacre is really heavily steeped in its time, better known as the Reconstruction era.

In general, according to History, Reconstruction refers to that period of time directly following the end of the Civil War, which included the rebuilding of the South, as well as its reintegration into the Union. In terms of more progressive reforms, well, things started out sort of slowly — President Andrew Johnson and Congress butted heads quite a bit — but after a couple years, Radical Reconstruction took hold, which saw the Republican party really pushing for change.

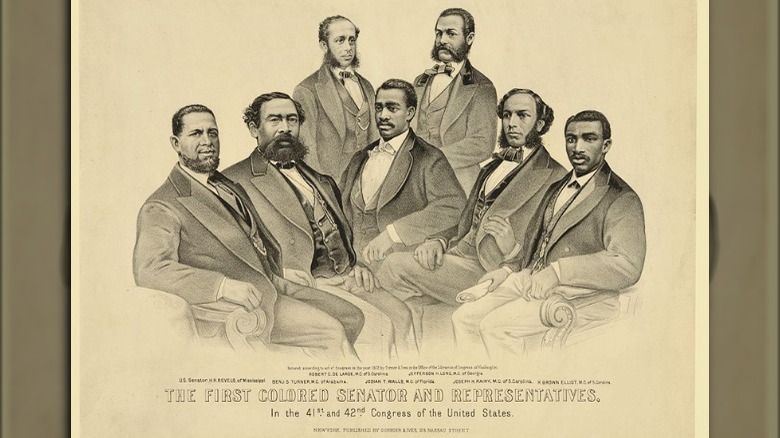

Through the latter half of the 1860s, African Americans had more of a voice in politics than they'd ever had in the past, holding public office and seats in Congress. There were also, of course, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments — citizenship and voting rights, respectively, for African Americans — the former of which Southern states actually had to ratify in order to be allowed back into the Union. On top of that were various other laws and programs to aid in economic development, with the federal government in general playing a decent role in helping newly freed African American citizens.

That said, though, Reconstruction definitely had its pitfalls, between the federal government rescinding its support for progressive reform and the Southern states resisting change at every turn.

Resistance to Reconstruction

To put it really simply, the South absolutely hated the entire idea of Reconstruction. So it worked out that, under the term of President Andrew Johnson, they were sort of given free rein in just how to rebuild.

They did everything that they could to hold onto their old ways, including introducing laws called "black codes," which effectively restored the social structure of the antebellum South, restricting the movement and opportunities of newly freed African Americans (via 64 Parishes). As History says, the first of these were implemented as early as 1865 in Mississippi and South Carolina, and some of them did allow for a few freedoms — the right to buy land and testify in some court cases.

For the most part, though, that's where those freedoms stopped. African American citizens had to be able to provide proof of employment at the start of every year, and if they left that job earlier than planned, they could be arrested. The businesses they could own were limited, and the laws restricted their right to assemble and defaulted legal authority to whites.

Sharecropping also became a thing as African Americans tried to make a living as independent farmers. They would make deals with white landowners for land to farm, signing a contract that said part of their crop would be paid as "rent." It was meant to sound fair on the surface but was very exploitative, with white landowners basically cheating African American farmers out of their profits.

The political context of the Colfax Massacre

Given the tensions between pro-Reconstruction Republicans and Democrats who missed the antebellum South nationwide, it's no surprise that the same tensions could be felt in Louisiana's Grant Parish.

Distrust between Black and white people was high, and that wasn't really helped all that much by the demographic divide in the city of Colfax — 2,400 mostly Black Republican voters and 2,200 mostly-white Democratic ones (via Black Past). So when Louisiana's 1872 gubernatorial election rolled around, things were a complete mess. Voter intimidation, ballot stuffing, obstructing registration for Black voters — you name it, it was there, according to The New York Times. Things were bad enough that both parties declared themselves the victor, even going so far as to hold two separate inaugurations. It was a bizarre situation, and one that wasn't settled until February 1873, when a federal judge declared the Republican candidate the winner.

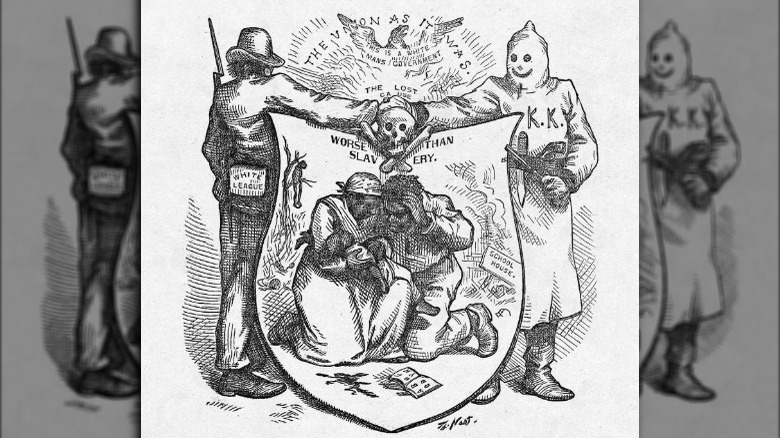

President Grant sent federal troops to Louisiana to protect the Republican candidate (via Smithsonian Magazine), and Republican officials began settling into their offices in the Grant Parish courthouse. By all rights, that should've been the end of things, but that wasn't even remotely true. Not even close. White Democratic supporters had no intention of giving up quite so easily, and given that this period of time saw the rise of groups like the White League and the Ku Klux Klan, well, things were about to get really bloody.

The white perspective on the Colfax 'Riot'

When it comes to what happened at Colfax, there are two ways to paint it: as a riot or a massacre. From the white perspective, this was an example of the former.

According to reports shared by Teaching American History, following the Republican victory in the election for governor, armed African American men began to assemble around the courthouse. White residents were reportedly scared of what was about to happen and wanted to call for peace, to no avail.

An eyewitness account from a man named John I. McCain described the ensuing violence, complete with threats thrown out from the Black militiamen (via The Atlantic): They threatened to take the white women and have their way with them, then proceeded to rampage through the city. They broke into homes and stores, stealing anything of value, leaving destruction in their wake. At one point, they apparently even broke into a home and destroyed the remains of the homeowners' child. White families were terrified and fled, and a group of white people were able to put together an army of their own, forcing the Black militia back to the courthouse. The building was burned down, forcing the Black militia to surrender (albeit purportedly while trying to attack under a flag of truce).

But bear in mind that McCain himself admitted that no one else at the time could verify his account, and Colfax mayor Connie Youngblood disputed multiple parts of McCain's story.

The 'Colfax Riot' or the 'Colfax Massacre?'

If you look beyond the disputed account of one person, what's the widely accepted story you're likely to find? Do the events at Colfax actually sound like a riot?

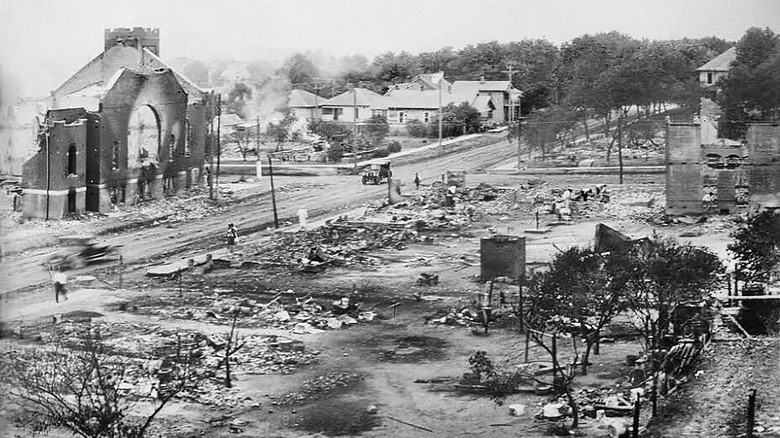

Following the 1872 election and the announcement that the Republican party had won that race, there were legitimate fears that militant white Democrats would try to take over the Louisiana government by force (via Smithsonian Magazine). As it turned out, that fear was far from unfounded because, as The New York Times explains, a sizable mob of heavily armed white supremacists — which included members of groups like the White League, the KKK, the Knights of the White Camellia (via Black Past), and former Confederate soldiers — showed up at the Grant Parish courthouse on April 13, 1873. They engaged and overwhelmed the Black militiamen who were there to protect the courthouse and the government officials inside. The white force attacked the courthouse with a cannon and eventually burned down the building; those who weren't burned alive were forced outside.

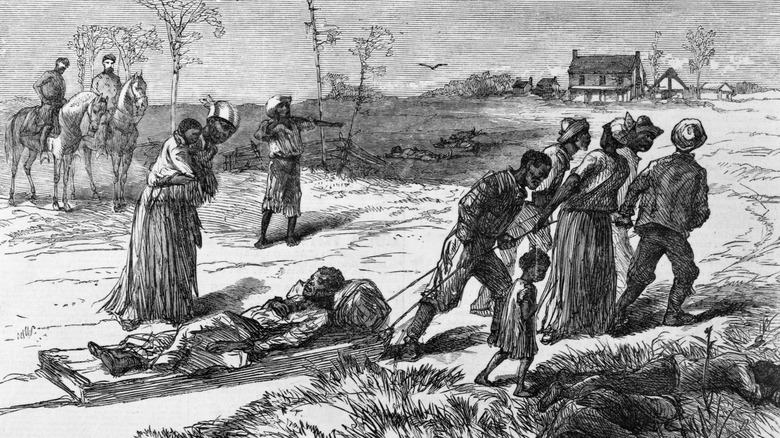

The majority of the African American force had to surrender at that point, though some of them fled. Surrender didn't guarantee them any sort of safety, though, with many of the men being executed on the spot. All told, the exact casualties aren't actually known, though many places will cite 150 African American deaths, while the white mob only suffered three.

Death was in the air after the Colfax Massacre

To generalize, the Colfax Massacre is considered by Smithsonian Magazine (and other sources) to be one of the worst cases of racial violence during the Reconstruction era (which, itself, was already known for quite a bit of violence). The murder of 150 African Americans during the confrontation is bad enough. On top of just that, though, is just how brutally everything went down.

Per The Atlantic, the white mob actually promised pardons to the Black militiamen who had been involved, but that didn't happen. Many of the men who surrendered at the courthouse were unceremoniously executed on the spot (via The New York Times). Aside from them, some 50 other members of the Black militia were rounded up over the course of the night and held prisoner. They were killed, too, either by shooting or hanging, long after the actual battle had occurred. According to Black Past, that murderous rampage didn't just end at the Black militia, with members of the white mob attacking innocent African Americans who weren't even involved in the incident at all.

And if you're wondering why the exact casualty count is unknown, well, that might have something to do with many of the victims receiving no funeral. A lot of the bodies were just thrown into the nearby Red River, hauled away, or tossed into mass graves (via Southern Poverty Law Center).

The Colfax Massacre was met with minimal legal action

You'd think that in a case where 150 Black citizens were slaughtered, there would be some sort of severe legal action taken, right? But you'd be wrong, in this case.

Following the events of the Colfax Massacre, United States attorney J.R. Beckwith had the job of prosecuting the case (via The New York Times). He came up with 32 counts to list to the court, as well as 98 defendants from the white mob, with the argument being that those brought to court were guilty of violating the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1870, more colloquially known as the Ku Klux Klan Acts. The United States Senate website explains that set of acts as being, basically, a way of enforcing the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. African Americans and their rights would be protected by the law, and groups (like the KKK) couldn't go around using violence and intimidation to violate those rights.

It seems straightforward, but Beckwith was up against a bunch of white supremacist attorneys, and by the end of the six-month-long trial, a whole seven people had been arrested. You read that right. Seven. Of 98. And the trail ended in a hung jury.

And things only went downhill from there. A retrial by a federal jury found only three of the seven guilty of conspiring to violate civil rights, but Supreme Court Justice Joseph P. Bradley came back just a little while later and overturned those verdicts, too.

United States vs. Cruikshank

The legal mess surrounding the Colfax Massacre was far from over. You see, that Supreme Court justice who overturned those guilty verdicts — Joseph P. Bradley — opposed Reconstruction and abolition (via The New York Times). One of the men whose guilty verdicts he overturned was William Cruikshank, whose name would be immortalized in United States vs. Cruikshank.

In 1876, the whole matter of the Colfax Massacre and its handling in terms of legality was taken to the Supreme Court. People were divided on what should happen, and at the end of the day, the Supreme Court sided with Cruikshank and Bradley, concluding that overturning the guilty verdicts was the right call.

Why? Chief Justice Waite's statement (via Teaching American History) pretty much said that the federal government was way out of line by taking part in any of this. Any power not explicitly granted to the federal government by the Constitution falls to the purview of the states; trials for conspiracy to commit murder (which this technically was) were the responsibility of the states. On top of that, the Fourteenth Amendment only applied to governments acting to subdue African American rights: Individual people (like those who participated in the massacre) didn't really count and could do what they wanted. And the court ruled that, technically, there was no proof that the massacre was racially motivated — that was apparently only speculation and not proven.

The Supreme Court had spoken, and it set a dangerous precedent by doing so.

The federal government's powers were diminished because of the Colfax Massacre

Supreme Court cases have had a tendency to set precedents: There's a reason why there are quite a few cases known by name. Roe v. Wade is central to abortion arguments, Brown v. Board of Education helped along the Civil Rights Movement, and there are others besides. United States vs. Cruikshank is similar, though the things it implied are far less positive.

In the abstract, the powers of the federal government were slashed. By saying that the rights guaranteed to African Americans were only protected from being taken away by the government, the Supreme Court also said that the federal government had basically no power when it came to prosecuting hate crimes (via Smithsonian Magazine). It took away any ability for the government to effectively protect recently freed African Americans, despite the progress that was seemingly made by the Reconstruction-era amendments (via The New York Times). White supremacists basically had free rein to do whatever they wanted, with very little fear of actually seeing any sort of notable legal consequence for their actions. For the most part, the U.S. government could do very little about hate crimes, and in the rare case that they did, it was more than possible to find legal loopholes to fix all their problems.

As for Black Americans? They learned that they were at a disadvantage when trying to protect their own rights.

The rise of the Jim Crow era

Talking about the abstract idea of the power of the federal government is one thing, but what about the more concrete effects that came out of the Colfax Massacre and United States vs. Cruikshank? And what about the long term?

According to 64 Parishes, the Jim Crow laws fall perfectly into both of those categories. This whole debacle around the Colfax Massacre ultimately led to the Supreme Court saying, effectively, that the federal government couldn't prosecute hate crimes committed based on race. Add to that the black codes that were already legal throughout the South, and really, Jim Crow wasn't all that far behind (via 64 Parishes).

With a perfectly paved path ahead, Southern governments could start restricting African American rights without directly taking them away — doing things like requiring literacy tests in order to register to vote. Then there was Plessy vs. Ferguson, better known as the court case that originated the "separate but equal" argument for segregation, which ran rampant through American society throughout the 20th century (and was later overturned for being inherently paradoxical).

The point is that the Colfax Massacre and the legal actions taken in its aftermath set up an environment where white supremacy and racially motivated hate crimes were completely legal. Segregation and violence could be expected to go unpunished, and the ideas of the antebellum South could live on.

Monuments to the Colfax Massacre

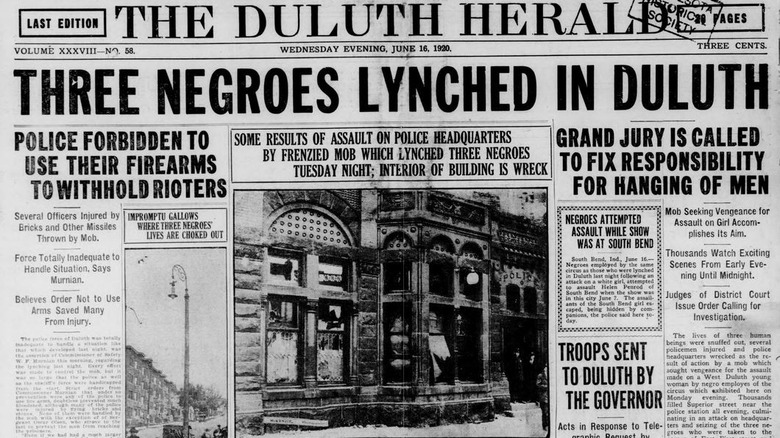

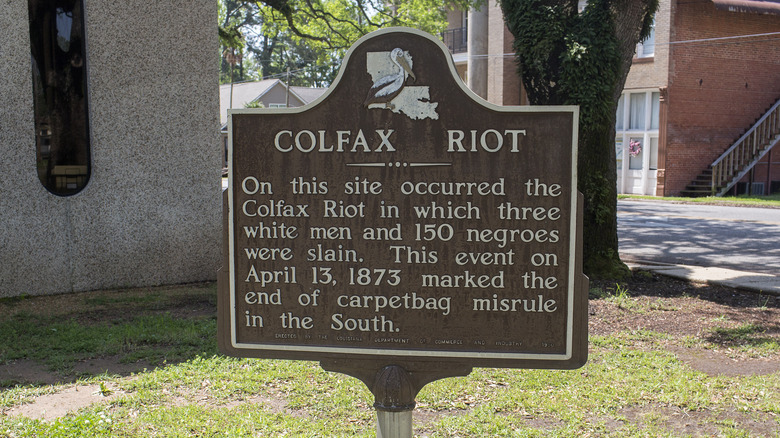

On the whole, there really isn't all that much discussion about the Colfax Massacre, and it's been largely forgotten by history. Even so, there are a few — frankly surprising — monuments to it standing in Colfax itself.

The first is a white marble obelisk standing in a local graveyard, as described by The Atlantic. It stands in dedication to the three white men who died during the massacre, explicitly saying that they fought for white supremacy. The African Americans who died that day don't have a memorial like that.

The second monument is a plaque that stands near the courthouse. Erected in 1951, the plaque refers to the Colfax "Riot" (not Massacre) and commemorates it for marking "the end of carpetbag misrule in the South" (via Smithsonian Magazine). Because this bloody April day is apparently most important for ending supposed Northern Republican (or carpetbagger) tyranny in the South.

Clearly, there are problems here, but according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, no one really cares enough. Even in a day and age where people call for Confederate monuments to fall, these still stand. That said, maybe it's not the worst thing. Colfax mayor Ossie Clark stated in 2018 that the memorials should stay as a reminder of what happened and a way to learn from the past, that people should have conversations about what happened to better understand where we're at today. But the language should be changed from "riot" to "massacre" all the same.