Creepy Things That Were Considered Normal 100 Years Ago

America a century ago was an exciting place to be. New inventions like motion pictures, airplanes, and radio were making the new century more interesting and more entertaining, but also a lot creepier.

New political ideas and new technologies were transforming the way people lived as well as casting an ominous tinge over their lives. More than any before it, the 20th century was defined by scientific advancement. Unfortunately, as much as science is a process of often expensive and even lethal trial and error, so, too, was much of the 20th century.

Medicine, law, war, and entertainment were all very different 100 years ago — not always for the better, sometimes for the worse, and frequently for the downright creepy. From police state authoritarianism to overwhelming racism and misogyny to who-thought-that-was-a-good-idea medical treatments, the steampunk ethos of the 19th century collided with the electrified 20th century with occasionally chilling results.

Leeches were medicine

When something is a synonym for "bloodsucker," we may hope society would find no use for it. However, as anyone who's dealt with lawyers or insurance agents knows, leeches have all manner of opportunities in society, including as literal bloodsuckers.

Starting in Egypt some 3,000 years ago, bloodletting has been a medical procedure for ancient cultures all over the world. Leeches were often used in this regard for a variety of reasons. They were extremely convenient for physicians: Not only were leeches actually designed to suck blood, but could also get into the trickier — and more sensitive — nooks and crannies of the human body.

While originally used in ancient Greece to balance the body's "four humors," leeching became an increasingly popular prescription for an increasing number of ailments and conditions. Fevers, flatulence, toothaches, and even hemorrhoids could be treated with leeches. Although leeching had effectively disappeared by the middle of the 20th century, it remained a folk remedy in some places in the U.S. and has actually experienced a resurgence in legitimate medical circles in the 21st century. Today, doctors and medical researchers are using leeches to test and treat everything from cancer to osteoarthritis.

Arranged marriages were common

The institution of marriage has evolved over the centuries. What it looks like, who is involved, what responsibilities you may have, and even the very reasons for marriage have undergone profound change since earlier times.

Marriage as a formal arrangement between unrelated families may go back tens of thousands of years into the Stone Age. After genetic testing on some Russians who died 34,000 ago, researchers with the Universities of Cambridge and Copenhagen theorized that marriage may have begun as a conscious strategy to avoid inbreeding. For a very long time, marriage was little more than arrangements for men to produce and accumulate heirs. In fact, traditional marriage is actually a very recent idea, as polygamy, or at least a system of womb-using concubines for the monogamous, was the norm for most cultures for most of history.

Child marriage was also common. The age of consent in some places was basically whatever dad said. For most cultures up until the last few centuries, marriages frequently involved very young brides and/or grooms. This has only comparatively recently begun to change — although there have been hiccups in this historical trend. The Centers for Disease Control calculated that about six percent of American women marry by the age of 18 today, says historian Nicholas Syrett (via CPR), while U.S. Census records reveal that in 1920, almost 12 percent of all American girls between 15 and 19 were married.

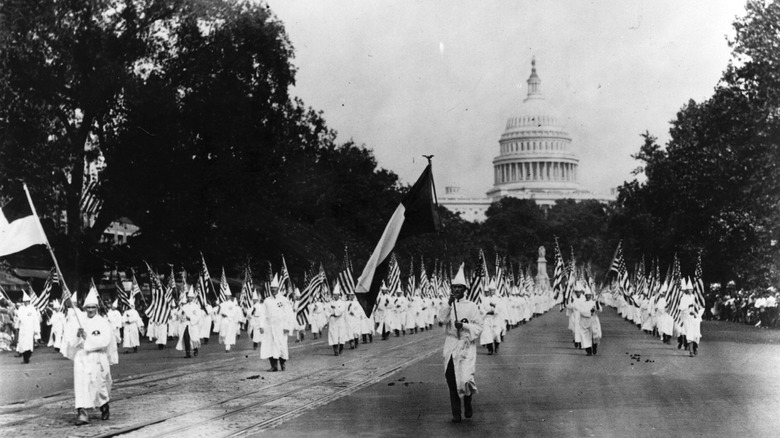

KKK marches were normal

America's origins were tainted by racism, but we fought a war to end that. However, Jim Crow laws became more powerful, a racist cheerleader became president, and by 1920, America was horribly racist.

The Ku Klux Klan had been ridden out of town on a rail in the 1870s by President Grant, but by the time Woodrow Wilson took office, the ranks of the KKK had swollen. Wilson seemingly did all he could to boost their recruitment and aims as well, from resegregating the federal government to actually hosting a private viewing of "The Birth of a Nation" at the White House, and for the first few decades of the 20th century, the KKK was a visible presence in many places around the country.

The KKK was such an open, accepted part of American society that they would publicly sponsor festivals, family gatherings, and beautiful baby contests. The Klan would host and officiate weddings and christenings. They had cars entered in races and baseball teams. "In some places I studied in Indiana," sociology professor Kathleen M. Blee told NPR, "the local KKK was listed in the city directory, along with sewing clubs and agricultural societies." They fielded candidates for public office, too — the political ties were so deep that the 1924 Democratic National Convention is often referred to as "Klanbake."

Bubonic plague was still a threat

Yersinia pestis is a pretty famous bacterium. It has the greatest stage name ever; the Black Death, and rocked the 14th century so hard that one third of Europe was killed. However, bubonic plague wasn't just a problem for Europeans hundreds of years ago: There were over 1,000 cases in the U.S. during the 20th century.

Bubonic plague is primarily transmitted by fleabites, specifically from fleas carried by rats, like the ones that came to the U.S. aboard steamships bound for San Francisco in 1900. That city's Chinatown hosted the very first American outbreak of plague, and it scared California's leaders so much that they conspired to hide it from the rest of the country. San Francisco's mayor and the state governor, along with their willing accomplices in California's media and business titans, managed to persuade the surgeon general of the United States to help cover up the plague outbreak. At least 172 people died before the outbreak ended.

The first 25 years of the 20th century saw over 500 cases of plague, and they would usually be in port towns. In 1920, Galveston, Texas, was home to another outbreak. This time, the city acted quickly. The source of the disease was discovered (rats), and Galveston embarked on a two-year rodent murder spree that helped end the outbreak with only 11 dead.

Animal corpses and feces were everywhere

Cities have always had to deal with traffic and pollution. Even ancient Rome had rules about where horses could go and when. But in the 1800s, cities industrialized and grew so that by the dawn of the 20th century, metropolises like New York depended on hundreds of thousands of horses for delivery and transportation.

It would not have been unusual to see goats, ducks, pigs, or cows walking through cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Sometimes, these animals, or the horses everyone depended on, would die in the streets and need to be carted off. However, transporting a several-hundred-pound carcass is difficult, and sometimes, they'd be left to putrefy for a while to make sawing them apart easier. The festering smells and disease-laden corpses were a public health hazard that few modern city-dwellers could imagine.

A horse can deposit between 15 and 35 pounds of manure and up to a couple gallons of urine every day. City leaders around the world faced a huge problem, and in 1894, The Times of London predicted (via Historic UK) that, "In 50 years, every street in London will be buried under nine feet of manure." Although automobiles and asphalt are what truly ended the age of the urban horse, it was in response to what some historians call "The Great Horse-Manure Crisis" that city planning and sanitation engineers became essential for future city growth.

Women's medicine was frightening

Health care in general wasn't a pleasant experience in the early 20th century, but it was particularly bad for women. It will probably be little surprise that women still faced challenges entering medicine. But they were also excluded from medical research for a very long time (so long, in fact, that including females in medical research trials was only made mandatory in 2016), which probably had something to do with the baffling diagnoses and treatments that women could expect.

One popular 1907 book on pregnancy, Henry Davidson Fry's "Maternity" (via The Week), instructed doctors to prep pregnant women: "The hair around the genitalia should be cut short with scissors or shaved, scrubbed with hot sterile water, and bathed with [acidic] bichloride solution." Another popular book of the same year theorized that the womb is directly connected to the clitoris and that birth pains could be treated by applying pressure "with the fingers on the terminal filaments of the sympathetic nerves in and around" the area.

A popular treatment to the dreaded female "hysteria," the symptoms of which could basically be any behavior that men didn't like, purportedly involved doctors giving patients a pelvic massage until they orgasmed. Eventually, a visionary hero arose and invented an "electromechanical" treatment, which would lead to today's, shall we say, adult toys.

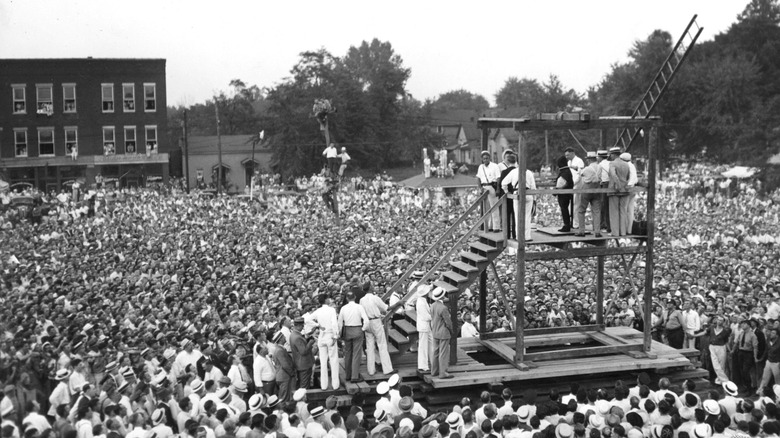

Public executions

From high infant mortality to the regular recurrence of deadly disease outbreaks to dead animals in the streets, it may be difficult to appreciate how closely acquainted with violence and death the average person was a century ago. The justice system of the day reflected the society it served: Traitors were shot, rapists were hanged, and justice was merciless.

Throughout its history, over 16,000 people have been executed in the United States. Like most countries and cultures, capital punishment was often a public spectacle in the U.S.A. In fact, the last public execution in the country was attended by as many as 20,000 people, fascinated by the fact that the executing sheriff was a woman. The negative publicity generated by the event, garnering headlines like "Ghostly Carnival Precedes Hanging" from Evansville, Indiana, encouraged lawmakers all across the states to ban the practice.

Of course, governments banning themselves from publicly killing citizens did nothing to deter civilians from doing it themselves. Lynchings were horrifyingly common in old-timey America: Only five states can say that nobody was lynched there from 1882 to 1968. Public vigilantism was frequently resorted to for all manner of crimes: for cattle thieves and murderers in the West, and for basically being Black in the South. Of the 4,743 people lynched in the country between 1882 and 1968, 72 percent were Black.

If you or a loved one has experienced a hate crime, contact the VictimConnect Hotline by phone at 1-855-4-VICTIM or by chat for more information or assistance in locating services to help. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

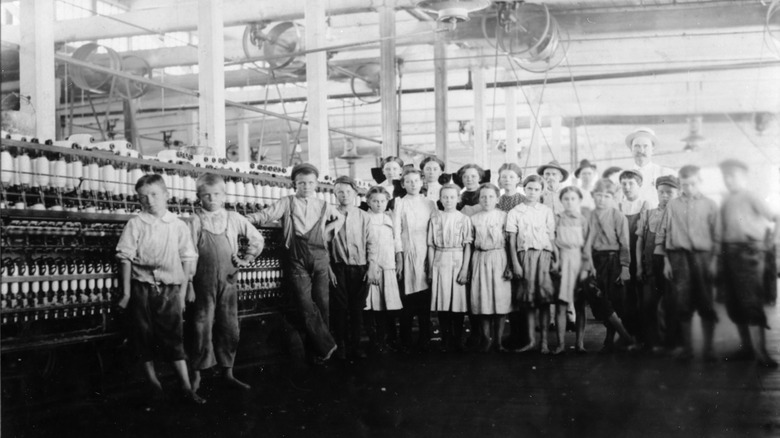

Child labor was used for everything

For most of history, a newborn baby was generally viewed as one part future laborer and one part old age insurance policy. Children were expected to work from a very young age, helping around the farm, house, or business. By the turn of the 20th century, as the economy evolved and urbanization continued, children were employed in a great variety of industries and trades.

In addition to the traditional farming and agricultural field labor that they'd always done, 100 years ago, rural youth could also be employed in resource extraction — mining, breaking up, and hauling coal. At coastal towns, they would be fishing, shoring, shucking oysters, or canning. In cities and towns of all sizes, children were employed by mills and factories, making everything from glass products to textiles to kitchenware to cigars.

The big cities had legions of children buzzing around as couriers, drivers, cleaners, newsies, and much more. Indeed, child labor was integral to just about every level of the American economy, but the children themselves usually didn't even get to enjoy their wages.

Eugenics was science and law

Eugenics was/is the pseudoscientific theory that humans can consciously improve the species through a breeding program for humanity. For decades, governments around the world tried to improve their citizens; not their lives, but the citizens themselves.

The president of the Natural History Museum said in his opening address to a 1923 eugenics conference (via Zebrafish), "For the worlds work give me a pure-blooded ... ascertain through observation and experiment what each race is best fitted to accomplish." In other words, responsible governments should make sure the individual races stay in their place and not pollute each other through interbreeding. These repugnant ideas continued, with some believing that the unfit should just be sterilized. "It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind," said Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (via the University of Virginia) in a famous case upholding sterilization laws.

In all, 32 states passed some kind of eugenics law at some point. Eugenics was popular and considered progressive. Leaders of organizations like Planned Parenthood and the ACLU joined luminaries like Teddy Roosevelt and Alexander Graham Bell in supporting eugenics programs. California, with its high levels of anti-Mexican and anti-Asian attitudes, was particularly aggressive — and successful. Over 20,000 Californians were sterilized in the 20th century.

The government tried to kill drinkers during Prohibition

On January 17, 1920, after a decades-long effort to convince Americans that society would be improved by banning liquor, the sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States was made illegal. They were wrong. America turned into a creepy steampunk dystopia where the government tried to poison you while cops and politicians took their orders from the Mafia and the KKK.

Resistance to Prohibition appeared immediately. Maryland flatly refused to enforce it, and many states and municipalities underfunded enforcement. Banning the production and sale of alcohol didn't diminish the desire, so, naturally, a market emerged to supply it. And since alcohol was now a most profitable substance, bootleggers and Mafia bosses who sold it had lots of money to bribe police officers, politicians, and judges. Police were openly corrupt, and since Prohibition was largely driven by racist, anti-immigrant, and anti-Catholic attitudes, it helped fuel the Klan's resurgence.

Thirsty Americans risked prison to buy beer. And sometimes their lives. Homemade booze, "bathtub gin," killed four times as many people during Prohibition as it did prior. By 1926, these deaths were less accidental and more deliberate. Since much of the homemade liquor was made using industrial alcohols, the feds increased the amount of methanol, a deadly poison, required to make industrial alcohols. Famed humorist Will Rogers quipped (via the CATO Institute) that "governments used to murder by the bullet only. Now it's by the quart."

Mental health care was scary

Health care might have looked scary for women 100 years ago, but mental health care was terrifying for everyone. It probably shouldn't surprise that an era obsessed with science and new technology might produce psychiatric treatments more akin to Philip K. Dick than to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

Treatment for mental illness was fashionable for eugenics supporters. States commonly prohibited marriage for individuals with mental health issues or went one step further and sterilized them. Over 65,000 mentally ill Americans were sterilized until the last such operation in Oregon – in 1981. Schizophrenia could be treated with insulin shock therapy, where patients are given progressively larger doses of insulin, leaving them at high risk for brain damage. One New Jersey doctor thought mental illness was caused by untreated infections and between 1907 to 1930, went on a spree of unnecessarily removing teeth, tonsils, and even organs from patients searching for the crazy-making disease, killing 30 to 45 percent of them.

But it wouldn't be the early 20th century without electricity and sexism. There was electroshock therapy, which induces seizures by electrocuting the patient and is actually still practiced today. Even as women fought for the right to vote, there were still doctors who thought female reproductive organs were linked to mental health issues, and sent women to asylums for supposed signs of insanity, which could be pretty much anything men didn't like.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Sports were bloody

Thanks to new inventions like radio, people were finding new ways to entertain themselves in the 1920s. It's often referred to as the Golden Age of American Sports, and Americans paid good money for athletes to perform ... or to watch men pummel concussions into each other or watch animals tear each other apart.

Cockfighting involves two roosters slashing each other to death while gamblers watch. It's one of the world's most ancient pastimes, and it saw a revival of interest in the 1920s. Dogfighting may be older still, and this decade saw it migrate from a sport for rural people to one for the inner city, possibly due to the influx of English and Irish immigrants. Just about any sport one could want to bet on, any competition between animals, or between men and animals, could be found in places like New York City and San Francisco.

More traditional sports, with actual human athletes, were also far more brutal than today. Even the bravest, hungriest NCAA third-stringer would hesitate to play football with what passed for protective equipment in the 1920s (although football's deadliest time was actually the 1960s). The king of sports, boxing, attracted thousands of spectators in the '20s and international audiences on the radio. Even though bare-knuckle bouts had been largely phased out over the preceding decades, over 200 boxers died in the ring that decade.

Mortality rates for childhood illnesses were high

Before vaccines were developed to prevent common childhood diseases, infections like measles, diphtheria, and others could and did kill. As recently as 1900, a parent with five children could expect to lose one before the age of 5.

Measles provides an illustrative example. Measles is very contagious, and about 90% of people exposed to a sick person who have not themselves been vaccinated or recovered from measles will likely fall ill. The death rate of measles varies widely, from something like 0.1% in wealthy countries with developed medical infrastructure to 30% in the most vulnerable populations. Measles also leaves a sinister parting gift: it directly attacks the immune system, and so acquired immunity to other germs may be lost after a measles infection. As if that weren't bad enough, occasionally a fatal, progressive encephalitis will show up in measles patients weeks or months after an apparent recovery.

Before the measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, almost everyone contracted the disease — it's just that contagious. Each year in the United States, about 48,000 people were hospitalized, about 1,000 developed potentially disabling or life-threatening encephalitis, and over 400 patients died. And measles was just one of the "normal" childhood diseases. Diphtheria, which causes a choking inflammation of the throat, killed up to 15,000 Americans annually during the 1920s. In the last big pre-vaccine U.S. outbreak of rubella in the mid-1960s, 2,100 infants died shortly after birth, with another 20,000 babies born with rubella-linked disabilities.

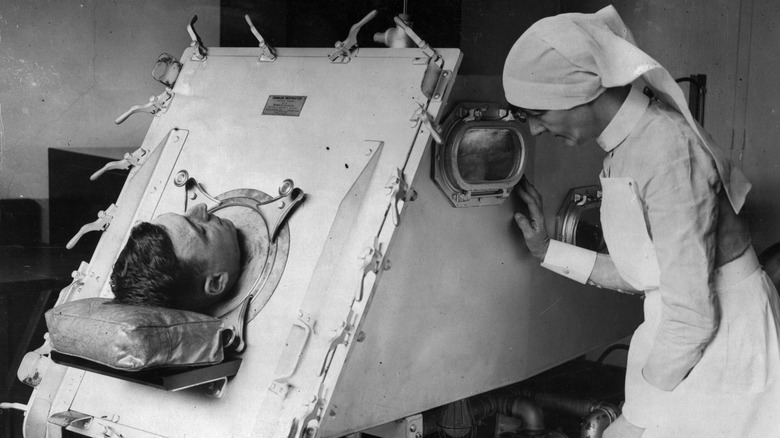

Childhood diseases could lead to lifelong disability

A century ago, even those children who survived serious bouts of illness might not have been able to return to their previous lives. Various illnesses could leave sufferers disabled, but the classic example of a sickness that could leave its victims with life-changing complications was polio.

Polio — poliomyelitis, to give it its government name — has been preventable with a vaccine since 1955; before then, it had ravaged populations as far back in history as ancient Egypt. The polio virus attacks the nervous system, potentially causing paralysis or weakness in the muscles connected to affected nerves. Before the vaccine became available, thousands of Americans died in the worst polio outbreaks, with many more confronting long-term disability.

Many polio survivors needed mobility aids, relying on crutches, braces, or wheelchairs as their muscles wasted in the absence of input from damaged nerves. The most seriously affected survivors found themselves unable to breathe alone, requiring devices like the iron lung. An iron lung is, in effect, a canister in which a person who needs breathing assistance lives. Developed in 1927 and first used the following year, the device creates a vacuum around the body to let the lungs passively expand, then repressurizes to force exhalation. If the electricity goes out, someone has to hand-pump the apparatus until the juice comes back. People could and did live for decades in iron lungs, but it was at best a difficult adaptation for patients and their families.

Anti-Semitism was in its American heyday

Antisemitism is a very old problem, but in the 1920s and 1930s, the United States embraced it as enthusiastically as if it were a hot new trend. The waves of immigration from Europe included many Jews fleeing persecution, particularly in Russia. They were generally safer in the United States, but a universally warm welcome was not presented.

Antisemitism in the United States was common even among elites. Harvard and other universities closed their doors to Jewish students from 1922, not barring them entirely but admitting only tightly limited numbers. Henry Ford, one of the country's richest men, had as a side project a weekly newspaper called the Dearborn Independent, which blamed "the International Jew" for various moral and political ills, including World War I. (For the record, neither Archduke Franz Ferdinand nor his assassin Gavrilo Princip nor Kaiser Wilhelm himself was Jewish.)

Hitler loved Ford's rantings, even having some of them translated and reprinted in Germany. Ford was joined in his hysteria by figures like Father Coughlin, a Roman Catholic priest who developed a popular and essentially fascist radio program, and Charles Lindbergh, the record-breaking aviator and celebrity who toured Germany as Hitler's guest. And when Hitler's plans for genocide neared enactment, the United States' doors remained closed to most Jews trying to flee.

Worker safety was nonexistent

The early 20th century had precious few legal protections for workers, even for situations that now seem like obvious hazards or unacceptable risks. A 1905 Supreme Court decision in the case Lochner v. New York had struck down a state law limiting the hours people could work, on the grounds that Lochner's employees should be "free" to work 18-hour shifts if they "wished." Of course, given the need to earn money to exchange for goods and services, these workers were not necessarily completely free to shop their labor around and agitate for safe conditions.

The generally slow progress made on workers' rights in the first decades of the 1900s was pushed along by reformers horrified by a 1911 conflagration at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. (A shirtwaist is a woman's blouse.) Cotton and paper debris on the floor of a factory occupying the upper floors of a downtown Manhattan building went up, killing 146 employees, mostly immigrants and women. The fire exits collapsed under panicked people trying to evacuate, while others were trapped by locked interior doors and took their chances out the windows. The factory owners were acquitted of manslaughter and in fact made a subsequent profit through light insurance fraud, but the horror and scandal did bring worker safety issues to greater public and government attention.

Violence and martial law were common responses to organized labor

If you decided to join forces with your fellow workers, unionize, and advocate for better pay and conditions, you needed to know you were in for a potentially violent situation. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the profusion of "labor wars" in the United States, which were tense and sometimes bloody clashes between management and labor that could and did lead to deaths. The tension relaxed somewhat when legislation in the early 1930s guaranteed the right to form and join labor unions.

After the emergence of the Soviet Union in 1917, anti-labor actions were able to present themselves as a resistance to communism, which presumably helped solidify local support for beating up steelworkers. Business interests and their government allies went to truly startling lengths to maintain control: Gary, Indiana, was placed under martial law in 1919. Troops were also sent to West Virginia in 1921 to intervene in a long-running dispute between miners and mine owners in West Virginia. Some 16 people had died in the months of skirmishing before the troop deployment, and one of the labor leaders, Bill Blizzard, was later tried (and acquitted) for treason against West Virginia.

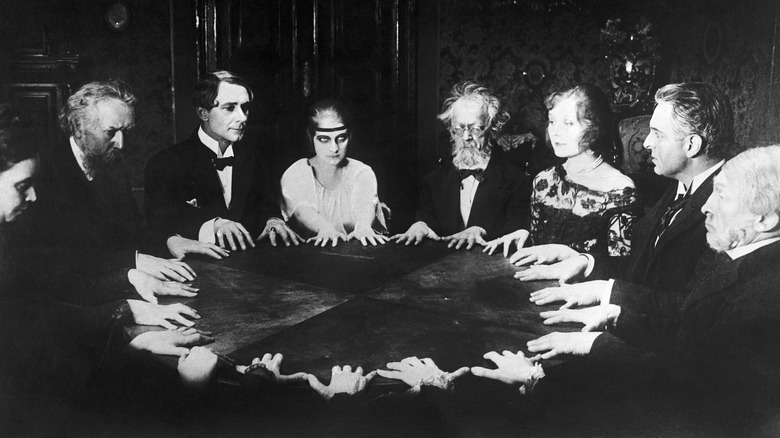

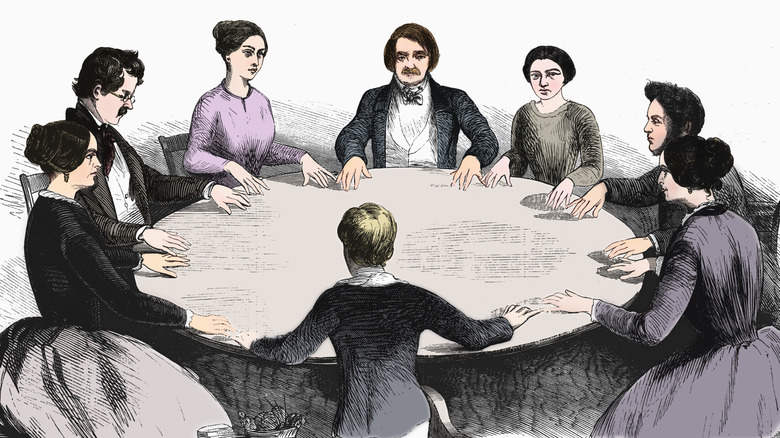

People were having a lot of seances

Spiritualism, a quasi-religion that can involve seances and mediums to communicate with the dead, began in about 1848, but the belief system enjoyed a spike of renewed popularity in the United States and Europe during the 1920s. World War I and the Spanish flu epidemic had left a lot of bereaved people on both sides of the Atlantic, and with the support of well-known people like Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, creating an aura of credibility, spiritualism's offer to connect those on earth with their loved ones across the veil appealed to a number of people.

Spiritualism never really rid itself of frauds for the simple reason that people like both proof and for exciting things to happen. Levitation, disembodied voices, and ectoplasm – a sort of magical goo some mediums claimed to be able to produce — spiced up seances but did not ultimately actually connect people to their dead loved ones, or even dead people they hadn't liked much. Belief in the basic ideas of the movement waxed and waned over the following decades, with another burst in England after World War II and a burgeoning population of practitioners in a Brazilian offshoot up to the present.

Food safety regulation was in its infancy

Abraham Lincoln established the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1862, despite having quite a full inbox that year, beginning a several-decade-long journey of jerky and irregular progress in American food safety. The Food, Drug, and Insecticide Administration spun off from the USDA in 1927, soon dropping the "and Insecticide" from the name, and in 1938, the new agency was empowered by legislation to set food standards in the United States.

Interim developments point to some of the issues consumers faced before a robust food safety infrastructure existed, with meat — which involves the complicated tasks of managing live animals and reducing the risk of spoilage — often at center stage. Half-hearted measures intended to prevent the import of sick animals or their butchered meat were in place in the 1860s, but lackluster enforcement meant that diseased animals still arrived and consequently spread whatever illness they had. In true American fashion, the government took the issue seriously when it hurt sales of American meat abroad, and from 1890 American meat was inspected, but only when it was exported.

In 1905, a novelist named Upton Sinclair, who had gone undercover in meat processing facilities, used the experiences to write "The Jungle," a gross-out polemic against bad meat wrapped in a tearjerker novel about down-on-their-luck Lithuanian immigrants outside Chicago. It flew off the shelves and presumably ruined quite a few dinners, in turn leading to 1906 legislation directing the sanitary slaughter and handling of meat.

There was lead everywhere

Unfortunately, lead carbonate produces an excellent white paint. Opaque and perfectly lilies-in-moonlight white, "lead white" has been used since antiquity and really only has one serious flaw, but it's a doozy: It's made out of lead, and it will kill you. Even with sublethal doses, lead can cause serious health issues, especially in children, and low-level lead poisoning has been blamed for spikes of violence under the theory that brain damage from lead boosts aggression.

In the 1910s, Dutch Boy paints (a subsidiary of the National Lead Company) were advertised with an appeal to "white-leaders," a probably imaginary group of everyday Americans who believed in nothing more than the beauty and glory of lead paint. While most people don't think about paint as much as Dutch Boy executives had hoped, the campaign does indicate a willingness to go all-in on lead and spoke to the wide use of lead paint in homes. Children, being children, would occasionally eat paint chips and get lead poisoning, but even passive absorption from dust is not good for anyone. Awake to this danger, the League of Nations, the forerunner to the United Nations, banned lead paint in 1922, but the good old U.S. of A. kept painting its interior walls in lead white until 1978.

Paint wasn't the only source of inadvertent lead contamination in 1920s America. In 1921, scientists realized that adding certain lead compounds to gasoline made car engines run more smoothly, and though phase-outs began earlier, the United States permitted lead in gasoline until 1996.

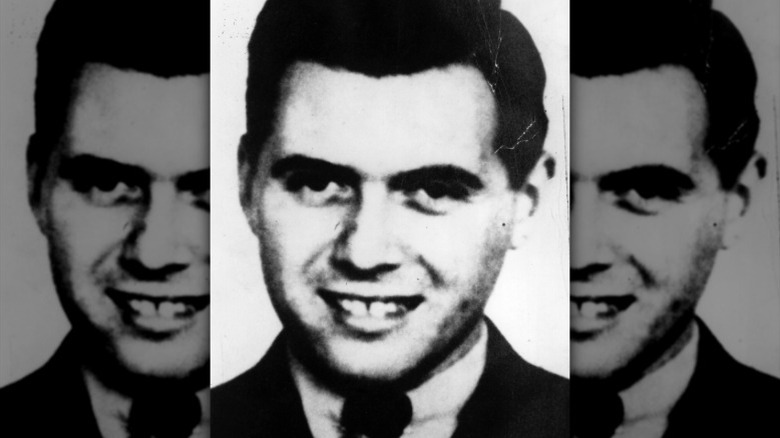

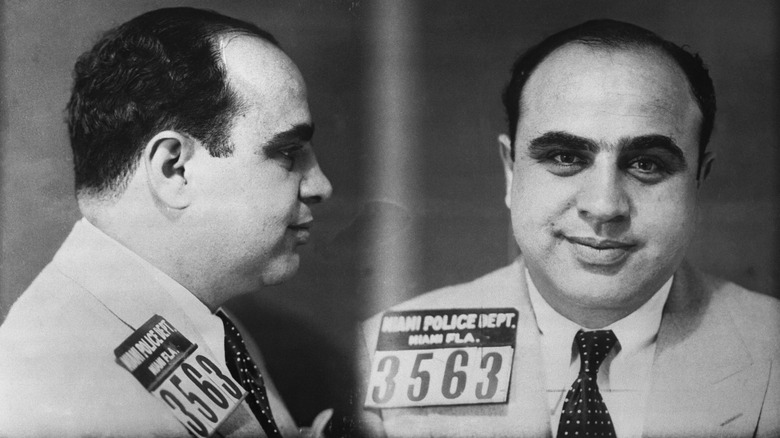

Organized crime flourished

The 1920s were the heyday of American organized crime, driven largely by Prohibition. Americans, taken as a group, enjoyed pretending that they favored Prohibition but didn't actually want to stop drinking alcohol, and so big and complicated illicit enterprises emerged to provide thirsty citizens with the sweet, life-giving booze that made those energetic flapper dances possible. Another factor encouraging organized crime was a shaky post-war economy in the early 1920s: Unemployment was rising, as was immigration, and too many people were chasing too few jobs. However, the underworld was always hiring.

The business opportunities provided by Prohibition encouraged many small organized crime outfits to consolidate, but the new and bigger groups continued to fight for territory and market share just as their less impressive predecessors had done. As Americans continued to rely on illicit sources of alcohol to get tanked, gang violence flared, with one of the epicenters, Chicago, seeing up to 400 gangland murders a year during the 1920s. Between the power offered by the money it brought in and the need to keep at least some public officials willing to look past it, organized crime began to encroach on public life in some cities, with crime bosses pulling political strings.

Prohibition was repealed in 1933, and the drying up of this income (if not the hoped-for drying out of the country) sent organized crime into retreat. Some organizations dissolved, while others simply pivoted to drugs.

A trendy card game was blamed for a murder

Today, bridge seems like a decidedly old-fashioned card game. The New York Times ended its bridge column in 2015, after decades of inscrutable diagrams and phrases like "if West had a spade void, he would have led a high diamond as a suit-preference signal." But in the late 1920s, bridge was a hot new fad — and like jazz, Dungeons and Dragons, and all the other hot new fads before and since, a murder was blamed on it.

During a 1929 game of bridge, Myrtle Bennett, a Kansas City woman, scolded her husband for playing poorly; he reacted by slapping her and ending the game. (This all happened in front of their neighbors with whom the Bennetts had been playing.) The Bennetts continued to argue until Mrs. Bennett left the room, grabbed a revolver, and most permanently ended the argument by fatally shooting Mr. Bennett. She was acquitted in the sensational trial that followed, despite having fired either twice or four times, according to the varied accounts.

During the trial, newspapers and magazines printed sample bridge hands to indicate just how terrible a player the late Mr. Bennett might have been. Helpfully, the jury even ruled it an accidental discharge of a firearm, allowing the theoretically bereaved Mrs. Bennett to collect life insurance. Mrs. Bennett faded from headlines after her release, but reportedly continued to play bridge.

There was no short-term severe weather warning system

As anyone who's ever tried to pack for a vacation knows, weather forecasting is not and likely never will be completely exact. In the 1920s, predictive abilities were weaker than they are now, and advisories like tornado warnings were unavailable until 1948. Weather reports in the 1920s addressed this problem by refraining from using the word "tornado" in forecasts to avoid frightening people.

One of these see-no-evil, speak-no-evil weather warnings meant that residents of Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana were unprepared on March 18, 1925, when the deadliest tornado in American history formed. Effectively destroying nine towns and dozens of farms along its 219-mile path, the Tri-State Tornado was record-breaking in its length, duration, and death toll, killing 695 people and barrelling along at an astonishing average of 62 miles per hour. As an added calamity, storm rains several days later flooded the Wabash River, cutting off road access to the affected city of Griffin, Indiana. Modern technology now allows an average of 13 minutes of warning for approaching tornadoes, and hopefully, these warnings will mean that no new storms will be able to challenge the Tri-State Tornado's still-record death toll.

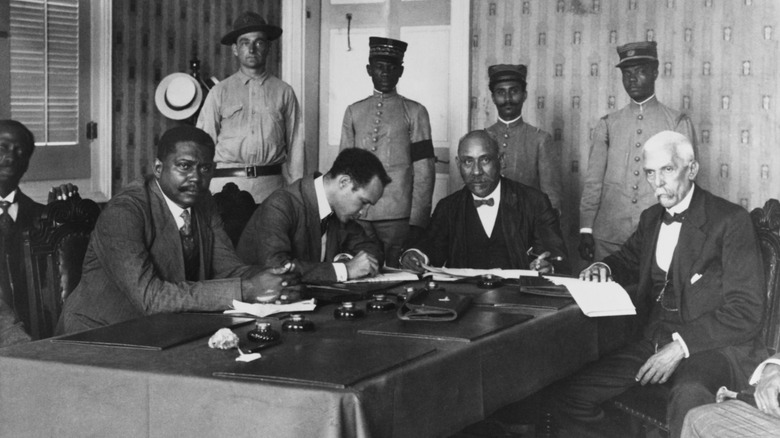

U.S. forces imposed forced labor and segregation in Haiti

The United States had been interested in Haiti for decades when it finally intervened in the smaller state in 1915. Haiti's location meant it could serve as a convenient refueling stop for American ships, and with World War I in progress, the technically still-neutral United States didn't want Germany to be tempted to involve itself in the Caribbean. So, after the admittedly startling death by mob violence of the Haitian president, the United States showed up and ultimately occupied Haiti until 1934.

The United States was, of course, still governed under segregationist laws, and the occupation government didn't see any reason to treat Black Haitians with more respect than they did Black Americans. American authorities took control of the Haitian armed forces and treasury, attempted to rework the Haitian constitution to allow foreign land ownership, and enacted a system of segregation in the majority-Black country.

It will not amaze most people to hear that this bullying treatment, especially in a country that owed its existence to a successful slave revolt, grated on the Haitians, and a rural revolt against forced labor flared in 1920-21 before a larger resistance arose in 1929. When United States forces finally left, over 11,000 Haitians had died, society had been militarized, and many Haitians had been taught to distrust outsiders claiming to bring assistance.