The U.S. Race Riots History Forgot

Ever see a pack of puppies playing together at the dog park? They don't care what other puppies look like or what color their fur is — they just want to make friends and have a good time. The moral? Be more like puppies.

Unfortunately, people aren't like puppies, and for generations, some have gotten all kinds of upset at the idea there are others out there who look a little different.

The result can be everything from verbal hatred to outright rioting, and the weird thing is that we've forgotten many of these incidents. Look at the Tulsa race massacre of 1921. Rioting destroyed 35 city blocks and left 36 dead (although some say the death toll was actually closer to 300) and around 800 injured. It's still believed that there are mass graves around that haven't been discovered yet, and just as shocking? It was almost forgotten in much of the U.S. until it was used as the backdrop of the opening for HBO's Watchmen.

So, that brings up an important question: What other incidents has U.S. history forgotten?

The race riots that led to the creation of a state capital

Today, we know the capital of Rhode Island is Providence, but in the 1800s, the area was made up of a group of small towns. According to Providence Monthly, there were two major incidents that made locals realize that they needed a better structure in place to deal with the conflicts of a growing population. The first happened in 1824.

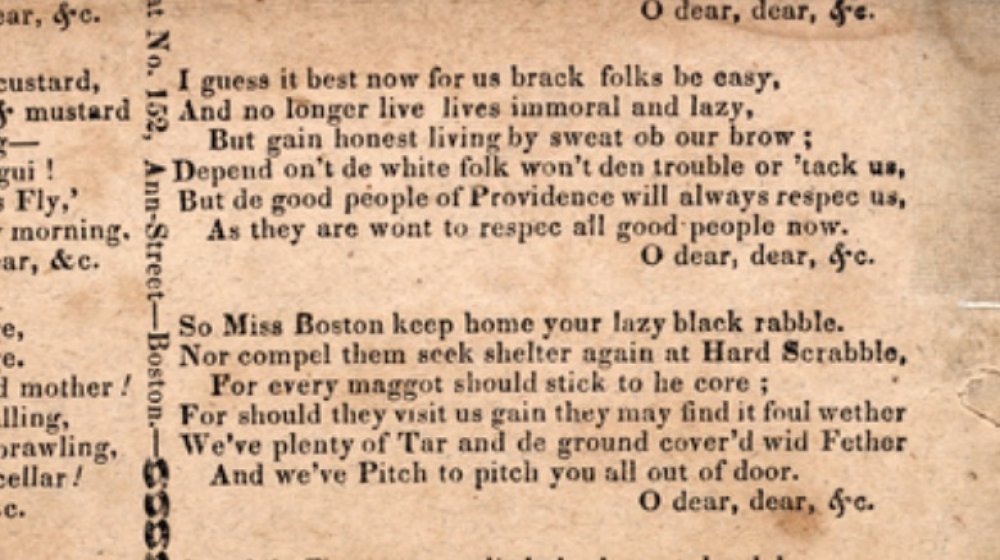

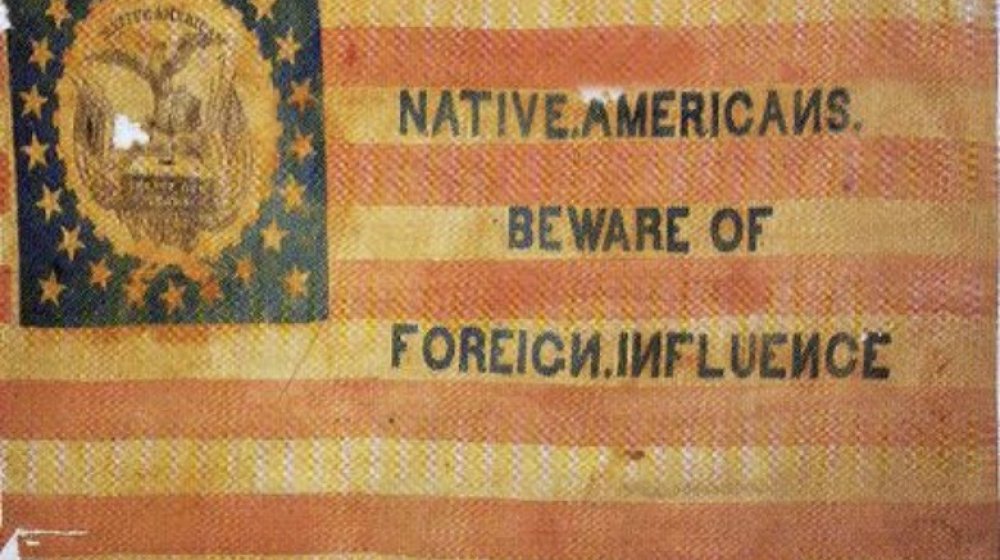

No one's really sure what caused the massive unrest, but the New England Historical Society says that it was rooted in unease over a changing, newly industrialized world. What were several hundred angry white people going to do about it? They rioted after a white man got mad that a Black man wouldn't step off the sidewalk they were sharing. They tore down the homes of 20 Black families living in an area called Hardscrabble and then stole their furniture. Later, papers ridiculed the victims with taunts, like the one pictured above.

Since there was no real authority, no one was really sure what to do about it. People were charged with rioting but ended up going free. In 1831, something similar happened in another area called Snowtown — and this time, the sheriff called in the militia. When citizens realized that the town councils had no power to stop any of this, they voted to make Providence a city and solidify law enforcement's authority.

The real roots of Lovecraft Country's home attacks

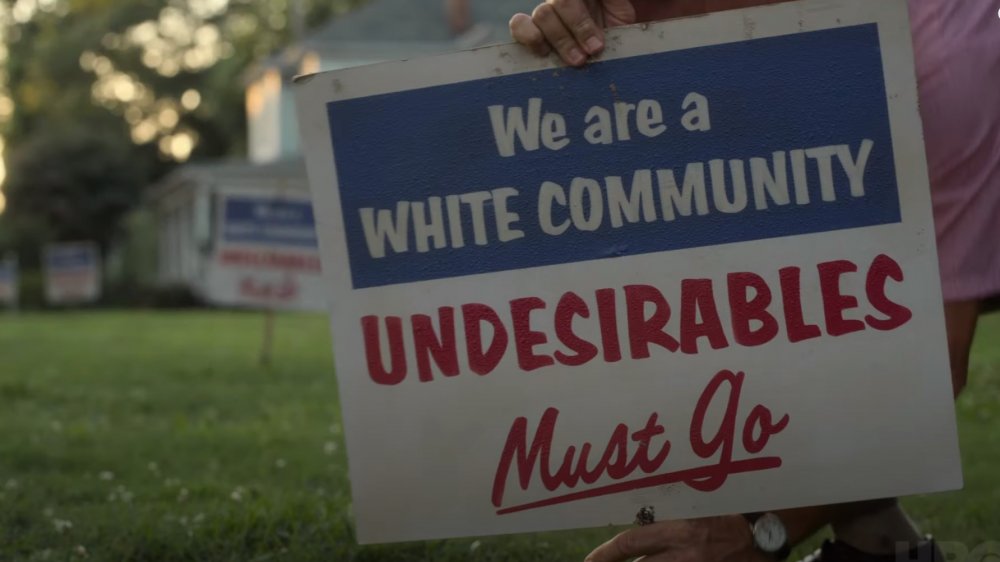

Your home is supposed to be a place of safety, but in the third episode of Lovecraft Country, that's not the case. No spoilers here, but we'll just say that the main characters suddenly find themselves fighting a group of racist neighbors fueled by serious hate. According to Men's Health, that episode was based on a horrific incident that happened in Cicero, Illinois. The year? 1951. The offense that caused a riot? A Black family moved into an apartment in a white neighborhood.

The family was made up of a Black war veteran named Harvey Clark Jr., his wife, and their two children. Before he moved in, the apartment building's owner was warned by town officials that it was going to cause "trouble," and he was also told that law enforcement would absolutely not intervene. They were on their own.

And they were. Their moving van was met by protesters, and police — and the fire department — did nothing as the mob ransacked and burned the apartment building. The violence lasted for days, and 21 families fled their homes. At its height, the mob grew to around 4,000 people, and sure, there were charges filed. But ultimately? The grand jury decided it was a "negro plot" and charged the building's owner, who'd rented to the Clark family. Eventually, town officials and police were indicted for civil rights violations.

Female Anti-Slavery Society? That was the last straw

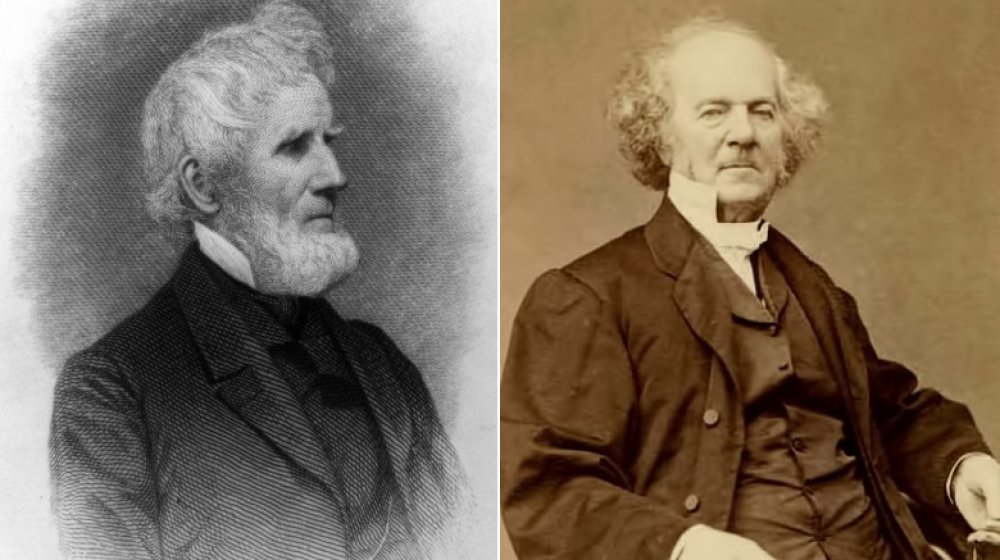

Lindsay Turley, director of collections for the Museum of the City of New York, stumbled across a map in 2012. She wasn't sure what it depicted, but it seemed to show an intersection in New York City, blockaded, with two figures fighting in the center and scores of others spilling down the streets. She and her colleagues started digging and came across a book excerpt that mentioned a riot in 1834. Eventually, they uncovered the story of riots that broke out in July. One side was led by people like the editors of the Courier and the Commercial Advertiser, who'd had enough with the activities of Arthur (left above) and Lewis (right above) Tappan, the brothers who helped found the American Anti-Slavery Association.

The brothers were behind something else, too — according to Black Past, they were also the creators of the Female Anti-Slavery Society. One other thing happened that seemed to be a major catalyst: Reverend Samuel Cox shared the not-wrong observation that Jesus would have been dark-skinned.

It wasn't long before mobs formed, and around 3,000 people started by attacking Cox's home. Churches were smashed next, and it wasn't long before the National Guard was called in. The violence continued until October, as it carried over into Five Points, where white residents were told to light a candle in their window so they weren't targeted by mistake.

Red Summer

When it comes to the worst years in history, 1919 is right up there at the top of the list. In addition to the Spanish flu, race riots were so widespread that at the time, it was simply called the Red Summer.

According to the National WWI Museum and Memorial, it started with the end of the war and the return of countless servicemen. Suddenly, there was a new fear: Black soldiers with military experience. And it's easy to see why the 380,000 Black veterans were angry. They'd been risking their lives for their country, only to return to be attacked and to see their friends, family, and neighbors killed for the color of their skin (via History). And that summer, they fought back.

Between April and November, there would be at least 97 lynchings, 25 separate riots in at least 26 cities, and one massacre that left 200 Black men, women, and children dead. The death tolls vary, but in Chicago alone, there were at least 38 killed, and 1,000 families were homeless.

It was perhaps best summed up by James Weldon Johnson, who coined the term "Red Summer" and wrote: "[...] it was almost an impossibility for me to realize as a truth that men and women of my race were being mobbed, chased, dragged from street cars, beaten, and killed within the shadow of the dome of the Capitol, [...]"

You know what a school stands for when "Dixie" is their song

In 2018, the Pensacola News Journal ran a story about a high school student who had her submission to the Escambia High yearbook rejected. The school said she had plagiarized her work, but she claimed there was something else going on: She said the school was "too ashamed to admit that our school was founded as an all-white school."

You've got to do quite a bit of digging, but you'll find that's just part of the story. In 1972, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights' report "The Diminishing Barrier: A Report on School Desegregation in Nine Communities" stated that the communities' reaction to desegregation was "one of resigned acceptance," and it was claimed that instances of violence — like one fight in 1972 that involved around 100 students — weren't racially motivated.

But The New York Times reported differently in 1976, running a piece on the continued debate over whether or not the school team should be called the "Rebels" and whether or not they should continue to fly the Confederate flag. Controversy finally came to a head with a parade featuring 120 members of the KKK. In the ensuing riot, four students were hit by gunfire (including one who was shot in the head and survived), 26 were injured, and several homes — including that of a state representative — were torched.

Currently, Escambia High School's team is the Gators.

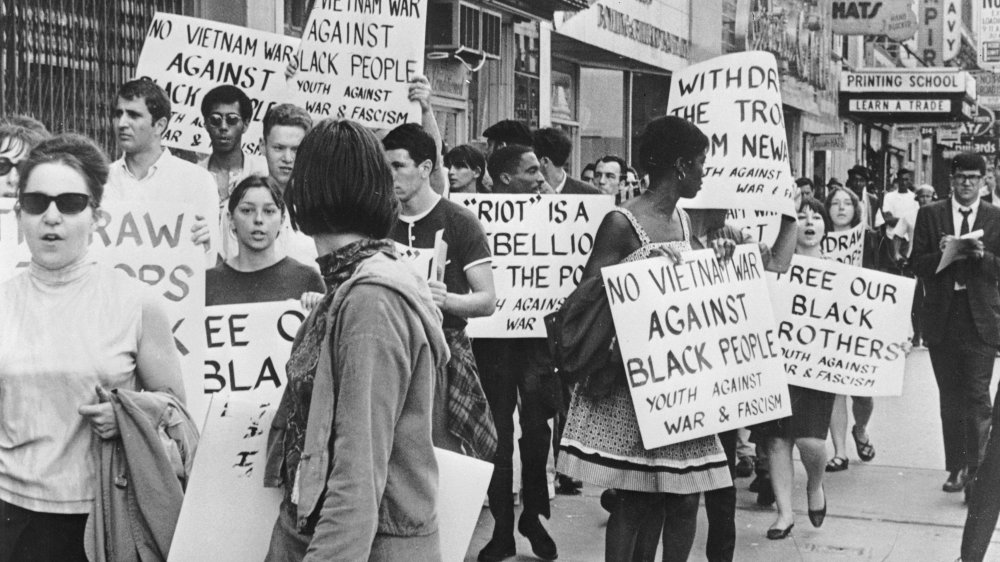

It wasn't just the Summer of Love

According to The Week, the first nine months of 1967 saw at least 164 riots breaking out in 34 states, and during the summer, the violence was at its peak. More than 150 cities descended into protests and rioting, and by the time things calmed down in September, at least 83 people were dead, and entire neighborhoods had been leveled. Racial injustice and police brutality was at the heart of it, but instances of violence were sparked by a number of incidents.

In Newark, New Jersey, it was the brutal beating of a Black cab driver who was dragged from his cab by police. (At the end of that riot, 23 people were dead.) In Detroit, it was a police raid on an after-hours nightclub. (There, 43 people would die.) The story was similar in cities across the country, where Black communities were laboring under the oppression of poverty, unemployment, a lack of social services, and power structures — the government and the police force — that were all-white. Things were so bad in some places that the National Guard was called in to try to end the riots.

And here's the thing: US News says that an in-depth investigation was conducted after the Newark riot, where another 700 people were injured. Most of those injuries were traced back to the weapons of the police department and the National Guard.

Justice shouldn't take this long

The scene? York, Pennsylvania. The time? The summers of 1968 and 1969. Both years, race riots descended on the city, incited in large part by police brutality and the widespread use of police dogs. According to the York Daily Record, the K-9 Corps was known for targeting young Black men with their dogs: On September 20, 1968, a fight broke out at a high school football game and ended when the dogs put seven people in the hospital.

Perhaps the best way to talk about these riots is to talk about those who died. On July 17, 1969, 17-year-old Taka Nii Sweeney was shot and taken to the hospital: Even though he would survive, it kicked off a rash of violence that, just four days later, would lead to the death of 27-year-old Lillie Belle Allen. The daughter of a preacher, she was in town visiting family when members of a white gang started shooting at their car. She was credited with saving the lives of the others in the car, and it took about 30 years for anyone to be charged.

Among those? Mayor Charles Robertson, who The New York Times says was arrested in 2001 after witnesses came forward to claim he had supplied ammunition and urged "leading commando raids" against the city's Black residents. Robertson (a cop in 1969) denied the charges and was acquitted. Nine others served time for their involvement in the events that led to Allen's murder.

Riot on the high seas

There are a few stories about what started the riot on the USS Kitty Hawk. One (via History) says it stemmed from the interrogation of a Black sailor who had been involved in a fight, another (via Navy Times) says it started over a cook who denied a Black sailor an extra sandwich, and still another (via The New York Times) says it started when ship personnel were told to break up congregating groups and only carried out the order when the group was made up entirely of Black soldiers.

Whatever really happened, it wasn't a good time to be aboard any ship in the South China Sea. It was 1972, they were deployed in support of troops in Vietnam, they were at sea for months at a time, and racial tensions were off the charts. One report says that the aforementioned events came to a head when a white mess cook stepped on a Black sailor's foot — when the cook rounded the corner and walked into a group of sailors angry about months of ill treatment, he was promptly beaten bloody.

The riot continued throughout the night, though the ship returned to its normal duties by the next morning — aside from 21 men being charged for rioting. It wasn't the only instance of riots in the Navy, either. In the following months, other ships would see similar incidents.

Bloody Monday

Here's the thing about a violent, bloody "us vs. them" riot: It's not always about the color of someone's skin. There are almost as many examples in U.S. history of people hating people just because their ancestors came from a different place, like what happened on a Monday in August 1855.

Just a few days after the riots that engulfed the city of Louisville, Kentucky, an Indianapolis newspaper ran an eyewitness account: A young mother fled a burning building, carrying her infant. A man grabbed some bedding from her and set it on fire, shouting, "We will learn you that Americans rule America!"

So, why was she targeted? She was both Irish and Catholic. According to Leo Weekly, both Irish and Germans were targeted. About a third of Louisville's population were recently settled immigrants, and thousands would flee after Bloody Monday.

It was led by the Know-Nothings, a political party who firmly believed that the Vatican was trying to take over the U.S. and that they were using Catholic immigrants to do it. In order to keep Catholics away from the Louisville polls, members of the Know-Nothings set up at polling stations and were instructed not to let anyone vote who didn't know the password ... and then hand out beatings. By the time it was over, around 100 businesses and homes were looted or destroyed, and although the official death toll is 22, estimates suggest it should be in the neighborhood of 100.

The City of Brotherly Love ... as long as you're not Irish

In 1844, Philadelphia was engulfed in violence and literal flames, and The Journal says it all started because of a Bible. When Bishop Francis Kenrick took over the largely Catholic diocese, he went to the city's school board and asked for permission to allow Catholic students to study the Catholic Douay Bible (while, it has to be added, he wanted to keep the King James Bible for the Protestant students). In the following confusion, the director of the city's schools suggested maybe they shouldn't teach any Bible at all, and that's when the wheels came off the cart.

On May 3, the American Republican party (who historians likened to the KKK) started gathering, and after a few more rallies, the muskets came out. A 19-year-old tanner was the first casualty, and Irish homes were targeted for burning. Within just a few days, entire sections of the city were on fire, and thousands of rioters were roaming the streets. By the time it was over, hundreds of buildings were gone, and no one's sure how many were dead. Why? Newspapers only listed the names of the dead "Native Americans," as they called themselves — not the dead Irish.

The "yellow peril" of the 19th century comes to violence

According to The Conversation, America's history of anti-Asian racism goes back a long way, and during the late 19th century, white nativists were fond of talking about what they called the "yellow peril." And the government listened, leading to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act. There were, however, a huge number of Chinese immigrants who were already in the U.S. — many had come in the mid-1800s and worked to build the country's railways before turning to prospecting.

On September 2, 1885, a group of white miners attacked their Chinese coworkers in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory. Both groups were employed by the Union Pacific coal department, but the disagreement was over who got the more lucrative areas of the mines.

The property damage that followed was somewhere in the neighborhood of $4 million in today's money, but that's not the worst. At least 28 Chinese miners were killed (some historians, says Politico, think the number was much higher), and 15 were wounded. The bodies of the dead and injured alike were thrown into the fires that had been started. Hundreds more fled, and federal troops were called in to keep the peace. Tensions were so high that they stayed until 1898, and meanwhile, newspapers didn't hesitate to take a side ... in favor of the riots and the killing.

Organized community-wide efforts should not include burning homes

On February 21, 1909, things went very, very badly for thousands of Omaha residents. That's when native-born Americans decided to run all the Greek immigrants out of town, and they absolutely did. According to The Pappas Post, the Greek families of Omaha were widely rumored to be "clannish, dangerous, immoral, and 'un-American,'" and other families decided to do something about it. After all, a Greek man had been seen speaking to an "American" woman, and when he was arrested, a fight broke out and quickly turned deadly.

What followed were riots that caused tens of millions of dollars in damages, and it was led by a mob of about 3,000. Anyone who was Greek — and was unfortunate enough to be caught by the mob — was beaten, including women and children. The newspaper coverage certainly hadn't helped: They had run petitions by civic leaders, appealing to residents to come to meetings and decide how best to get rid of the "filthy Greeks," with the Omaha Daily News going as far as writing, "Greeks are a menace to the American laboring man."

A footnote: Who was this American woman in question? She was 17-year-old Lillian Breese, who made her living by teaching English to Greek immigrants.