Seemingly Innocent Things With Creepy Origins

Your home is likely filled with some very creepy history. From your pantry, to your living room, to the workout equipment gathering dust in some forgotten corner, the past is waiting to surprise and maybe even shock you.

How do we think about the everyday objects in our homes, anyway? We're there every day, after all. It's easy to grow used to all of the devices that keep things moving or make our lives easier, so much so that they become practically invisible.

But the snacks in your kitchen could be tied to a Victorian-era crisis over health and morality. Those morbid Victorians sure loved a moral panic, per the Journal of British Studies. The board games in your hall closet are potentially tied to the story of a terrible childhood disease. Try going out of your house, and you'll encounter some deeply odd history there as well. Turns out that the radar keeping planes safely in the air began thanks to a project trying to build an anti-Nazi death ray.

Even beloved fairy tales aren't totally immune. One famous story collected by the Grimm Brothers in the 19th century shares a historic memory with medieval plagues and skin-crawling rat infestations. These are the truly creepy origins of the seemingly innocent things around you.

Graham crackers were supposed to fix a moral crisis

According to many people in the early 19th century, there was a serious problem plaguing younger folks. It was so awful, so shocking that few people dared to speak of it directly. You see, the youth were endangering their morals and their health through "self abuse." Doctors linked it to a bevy of mental and physical health problems, but the problem persisted. Who would save the wayward generation from themselves?

Enter Sylvester Graham. According to ThoughtCo, he blamed a poor diet for the supposed problem. It inflamed the passions and made the sort of evil in question all but impossible to resist. Graham, a vegetarian who abstained from caffeine, alcohol, sugar, fat, tobacco, and spices, knew that his carefully curated diet would be a hard sell. He had to start somewhere, though.

What the world really needed was a cracker. Graham's response to the moral dilemma was to develop a food so bland that it would quell practically any emotion: the graham cracker. But this wasn't the graham cracker you know and love today, JSTOR reports. Graham's first invention was carefully crafted to taste like almost nothing.

It did little to fix the problem it was created to address. Maybe that's because people started to mess with the recipe. Today's sweetened, refined version would be sure to horrify Reverend Graham.

Candy Land was invented because of polio

Candy Land is a dreamland of a board game, with candy forests, a mountain of gumdrops, and a swamp alarmingly filled with molasses. For the sugar-infused residents and visitors to Candy Land, it's just a regular day. But, for its inventor, it took a life-threatening disease to gain inspiration.

It all began in 1948, PBS reports, when retired schoolteacher Eleanor Abbott contracted polio. The viral disease can cause serious paralysis and even death. Today, we have a lifesaving polio vaccine, but Eleanor wasn't so lucky. The vaccine wouldn't be successfully cultured in human tissue until that very year, per Science. A widespread vaccine wouldn't come about until Jonas Salk and other scientists refined it in the 1950s, says the World Journal of Virology.

For Eleanor, treatment was available, but it only went so far. Even mild cases could still mean a long, boring period of convalescence. Patients were often isolated due to worries that they would spread the disease.

Because the polio epidemic of the 1940s and 1950s tended to strike children most, NPR notes, Abbott was in an isolated ward surrounded by sick kids. They needed something to distract them, so Abbott made a draft of a board game, the Atlantic reports. It was a hit. Abbott later pitched it to game company Milton Bradley. Candy Land became wildly popular amongst non-polio-ridden folks almost as soon as it debuted. It's still published today by Hasbro.

Treadmills were literal torture

It'd be easy to make a joke about how exercise on a treadmill is simply excruciating. Know that, if you were to find yourself in front of a group of 19th-century convicts, that quip could fall very, very flat.

That's because, in the early days of 19th-century prison reform, treadmills were used as instruments of torture, according to Mental Floss. Engineer Sir William Cubitt first debuted a "tread-wheel" for prisons in 1818. Inmates would be obliged to step up on the giant contraption, walking for hours on end. The kinetic energy generated by these poor souls would be used to turn gears that powered water pumps and grain mills. It might have been okay if it weren't for their eight-hour shifts and terrible diets. Weakened inmates could fall and receive terrible injuries on the treadmill.

Prison reformers claimed that the treadmill would quiet the beastly spirit of the worst offenders, The New York Times claims. Yet, those subjected to the experience were often profoundly affected. Oscar Wilde, imprisoned for "gross indecency with certain male persons" and forced to do time on the treadmill during his two-year sentence, died just three years after release. Eventually, the brutal treatment was exchanged for more low-tech but equally harsh labor like chain gangs and fieldwork.

Your silverware has a scandalous past

Today, Oneida Limited is one of the world's largest sellers of stainless steel and silverplate tableware, per BusinessWire. But that's not all there is to the Oneida story. As much as the company might want you to focus on the quality of their products or its kitschy midcentury advertisements, the real origin of Oneida is pretty wild.

It started with religious rebel John Humphrey Noyes. He was a "Perfectionist," the New York Times reports. For Noyes and his followers, that meant they believed that Jesus had already come back by 70 CE, meaning that the utopian Kingdom of God was already here. Some group simply needed to start acting like worthy children of God to take advantage. The group decided to go for it and moved into a large brick house in central New York state in 1848.

Noyes argued that, since early Christian communities were communal, the Oneida Community should share everything, too. That meant funds, living spaces, business ventures, and spouses, WBUR explains. Noyes eventually got the idea that the community would be able to produce the most perfect Perfectionists through selective breeding. Unfortunately, that led to abusive practices, breaking apart marriages, and coercing young and old community members into shocking situations.

Though the utopian experiment eventually fell apart, members still managed to hold on to their business dealings. Despite the failure of Noye's exploitative vision, part of the community survives today as Oneida Limited.

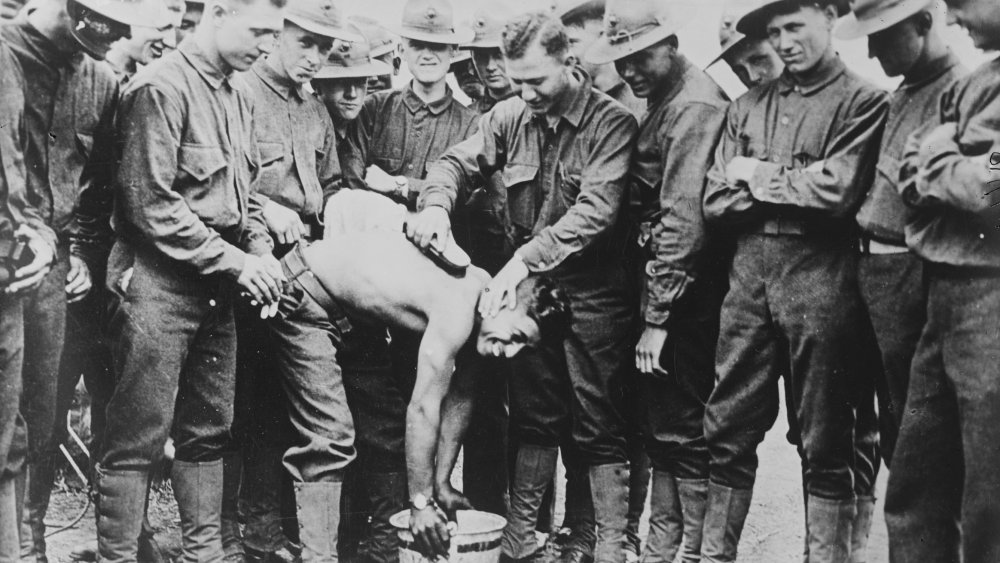

Cooties tormented World War I soldiers

Cooties are a playful scourge of the schoolyard. Young kids run around, chasing each other with the threat of cooties transmitted from another gender, or else heroically giving their friends the lifesaving "cootie shot." Though most children understand that cooties aren't real, they might not know that these bugs were once a real scourge.

Like so many awful things, cooties can be traced to World War I. As reported by Slate, soldiers in the trenches were plagued by painful and persistent body lice. It was part of a litany of misery that included chemical warfare, freezing mud, and enemy snipers waiting for you to make a mistake.

The painful bites and skin-crawling appearance of the insects were bad enough, but the little jerks spread sickness, too. According to the Microbiology Society, typhus transmitted by lice got so bad during the conflict that thousands of soldiers, prisoners, and refugees died of the bacterial disease.

After the memory of the war faded, the idea of cooties became more innocuous. They haven't lost their connection to illness, though. Cooties and cootie shots tend to surge in childhood circles whenever disease runs rampant, Smithsonian Magazine says.

Listerine was used for too many things

Nowadays, Listerine is meant to clean mouths and banish bad breath. That wasn't always so. According to the National Museum of American History, this product has been used to disinfect surgical tools, banish dandruff, clean floors, fight body odor, and treat diseases from smallpox to gonorrhea. Maybe it's easier to make a list of ways Listerine hasn't been used.

Dr. Joseph Lister didn't invent Listerine, but he was a Victorian-era doctor who learned the value of cleaning. Per Britannica, Lister discovered that, if he cleaned his hands and surgical equipment with carbolic acid, his patients were far less likely to die a painful death from sepsis.

While Ignaz Semmelweis first pushed the handwashing method in 1847, says The Conversation, he was roundly rejected. But by the 1870s, says the Mütter Museum, Lister's ideas took off and mortality rates plummeted. When chemist Jordan Wheat Lambert made his own antiseptic, he named it "Listerine" after the eminent doctor.

In the intervening years, Listerine has been used for a variety of weird things. One of the most harmful is the kind-of made-up scourge of "halitosis," or bad breath. While stinky breath certainly can happen, halitosis was actually a marketing ploy, Smithsonian Magazine claims. It was really designed to make people paranoid. In some ads, bad breath was blamed for tragedies like failed dates and lonely marital beds. The only way to fix it? Listerine, of course.

Trick or treating was originally about death and begging

For most modern folks, trick or treating is an innocent Halloween tradition. Kids dress up in costumes and go begging for sugar-packed candy. If you're lame enough to hand out toothbrushes or similar disappointing fare, you might find toilet paper decorating your home, but that's usually the worst of it.

Travel back to pre-Christian Europe, however, and you'll find that the practice was far more serious, per History. Halloween was originally the Celtic festival of Samhain when people would honor the dead by lighting bonfires and offering up sacrifices. If were an ancient Celt who wasn't keen on having ghostly visitors, you might dress up in animal skins to scare them away. A gentler tactic was to leave out some food to appease the spirits.

With the rise of Christianity, according to Smithsonian Magazine, these practices morphed into a tradition called "guising," where people would dress up and go door to door. They would beg for food and money, promising to pray for the souls of the dead in exchange. More prayers could help a soul move quickly out of Purgatory and into heaven.

The modern practice known as "trick or treat" came about in the 1930s, Time reports, and didn't really take off until the rise of the kid-friendly suburbs in the 1950s. Many of the modern traditions Americans associate with the holidays have only been around for a few decades.

A fairy tale may have helped a community deal with real tragedy

The Pied Piper of Hamelin is a folk tale collected by numerous writers. Though it's a story, could it be linked to a historic tragedy?

In the Grimm Brothers version, a stranger arrives at the medieval town of Hamelin, Germany. The people of Hamelin are preoccupied with a terrible rat infestation. The stranger, dressed in multicolored (or pied) clothing, whips out a flute-like pipe and leads the rats away with his music. The town leaders won't pay him, so the piper gets angry and later returns to lead the children of Hamelin away into the unknown. The adults are left to mourn their children.

According to Mental Floss, some of the details can't be true. Rats weren't added to the folk tale until the 16th century, meaning that the children couldn't have been carried away by a rat-bourne plague. There are hints that a real tragedy happened, the BBC reports. A since-destroyed stained glass window commemorates the children's disappearance, as do various written records and inscriptions. It indicates that some 130 young people disappeared in June 1284.

Some historians say that an economic depression caused younger townsfolk to move. The Pied Piper would have been a medieval sales rep, urging them to leave for greener pastures. Others think that they left on the 13th-century Children's Crusade, described by History as an utter disaster that led thousands of children from their homes.

We got radar because someone wanted a death ray

The 1930s in Britain were a tense time. Nazi Germany was ascending and, with the rest of the European continent vulnerable to takeover and enemies only a channel away, the people of Great Britain were understandably nervous.

Even worse, intelligence suggested that Germany was gaining alarming advances in technology. What were members of the British military supposed to do? Their idea, according to the BBC, was to create a death ray.

Two scientists at the Radio Research Station, Robert Watson Watt and Arnold "Skip" Wilkins, quickly determined that radio waves just wouldn't be powerful enough to knock out pilots at 3,000 feet above ground. Still, Watt and Wilkins recognized that the idea of radio waves was pretty intriguing.

They couldn't do anything too dramatic, thanks to that power deficit, but both understood that radio waves could reflect off surfaces. Was it possible to read those reflections and detect incoming aircraft before anyone could see them?

By 1940, they had developed the idea, called the resonant cavity magnetron. But, since their factories had been pounded by German bombs, they needed the Americans. That led to the formation of MIT's Radiation Laboratory, which, in collaboration with British scientists, developed the radar technology we still use today.

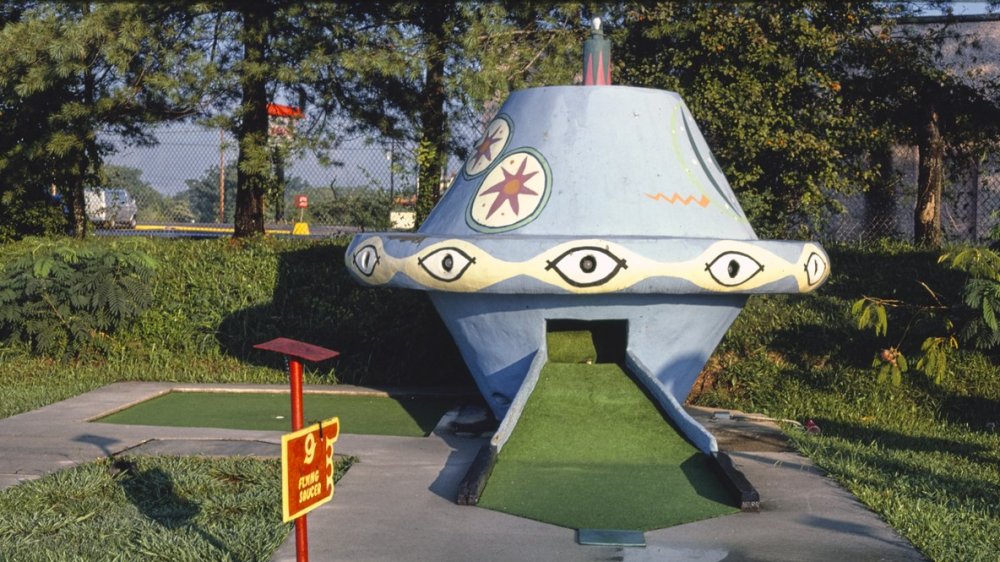

Mini golf was supposed to keep Victorian women proper

Mini golf seems pretty easy to understand. It's golf, but smaller, and with cool obstacles like miniaturized windmills. Beyond that, few really know the origins of mini golf. Who created it, and why?

There are actually multiple origin stories claiming to describe the rise of mini golf. One, as shared by Nutters with Putters, maintains that the game first arose in Scotland in 1867. That's when an 18-hole course was opened in St. Andrews, Scotland, specifically for female players. Women were allowed to putt through, says the story, but that was about all they could do if they hoped to remain proper Victorian ladies.

Yes, in this version of the story, mini golf was invented due to the twisted world of Victorian sexism. The sight of a woman swinging a golf club above her shoulders is said to have been rather crude. It may have been next to impossible, too, considering the cumbersome demands of 19th-century dresses and underthings.

According to How Stuff Works, this first mini golf course actually became rather well-regarded. Perhaps because the Ladies' Putting Club never tried to hit a hole-in-one through a giant clown face.

Dance marathons went from deadly serious to money-raising fun

Dance marathons are a simple model: dance as long as you can, with minimal breaks for sleep, food, and bathroom visits. The spectacle brings spectators and reporters, who then help generate money for a given cause. The Miracle Network Dance Marathon benefits Children's Miracle Network Hospitals, while the University of Iowa holds a similar event to support programs at the Stead Family Children's Hospital.

It's all very heartwarming and goes to support very good causes, but the history of dance marathons gets pretty dark. Decades ago, they were filled with desperate people trying to win money, gain fame, and not collapse or even die of exhaustion.

During the Great Depression, Atlas Obscura reports, dance marathons were already established as an entertainment option. The country's economic woes just intensified the stakes. Dancers who made it to the end could be awarded a hefty cash prize, which was a tempting alternative to breadlines and crushing unemployment. If nothing else, they were at least guaranteed food and shelter for as long as they could dance.

Some contestants even went semi-pro, the Guardian says, but it wasn't easy. They faced punishing hours, with one record-setter dancing for 82 hours. And it wasn't just blisters and aching joints that plagued these long-haulers. One man, Homer Morehouse, danced for a shocking 87 hours and then dropped dead of heart failure.