Huge Moments In The '90s We've All Forgotten About

After the rough and rocky decade we call the 2010s, the 1990s have emerged as the era we return to over and over again — the place we go to for some much-needed nostalgia and a reminder of more innocent times.

Whether it's binge-watching Friends and Seinfeld to get us through lockdown or the revival of '90s fashion and technology such as cassette tapes and Polaroid cameras, the last decade of the previous century is everywhere. And in many ways, it really was a simpler time. The internet was in its infancy, cell phones were only owned by yuppies, and phrases like "fake news" and "alternative facts" would have been met with blind incredulity. Oh, those lucky, innocent people of the past.

But that's not to say that the '90s were any less nutso in terms of world events and life-changing news than we are constantly bombarded with on our social media feeds today. There are some stories that define the era: the O.J. Simpson trial, the death of Princess Diana, and the extramarital misbehaviors of Bill Clinton in the Oval Office. But there are also some huge events that many of us have forgotten about today, happenings that, as seismic as they were, we don't typically associate with the decade that we all now romanticize so much. Here's a refresher course of some of the biggest unremembered news stories of the '90s.

The city bonds robbery, 1990

Everyone loves a good heist — especially if the details of the robbery have some glamorous or intriguing aspects to them, like a high-speed boat chase along the river of a major city or a devilishly devised tunnel through which the crack crew executed their well-planned escape. But as the '90s began, one of the world's greatest heists occurred in such prosaic and unsatisfying circumstances that, for a brief moment, the world's media believed that the story was a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The Guardian reports that in the City of London on May 2, 1990, at 9:30 AM, a 58-year-old man who worked as a messenger for a brokerage called Sheppards was transporting a bagful of bills and deposit certificates worth £292 million down a quiet side street when he was suddenly mugged at knifepoint. According to the Irish Examiner, the robbery was one of the largest in history, with only the $1 billion theft from the Central Bank of Iraq by one of the sons of Saddam Hussein exceeding it.

Though the underwhelming nature of the mugging suggested that the loss was the result of a small-time thief striking it lucky, a further investigation concluded that it was, in fact, the result of great planning by a criminal gang with connections to both the IRA and the New York Mafia. The bonds were eventually recovered, and the criminals were jailed.

The World Health Organization declassifies homosexuality as an illness, 1990

Sometimes you come across an old news story that really does show how far we've come. Back in 1990, after a decade in which the AIDS epidemic dominated the headlines and the gay community was continually in the spotlight, the World Health Organization (WHO) chose the date of May 17 to release a bulletin that would change the perception of homosexuality, both socially and in terms of policy for nations around the world.

From 1948, the WHO had classified homosexuality as a mental handicap, suggesting that being straight was a necessity to be able to function correctly and live a healthy life as a member of society. But in 1990, this was all to change.

According to May17.org – who have adopted the date to host the annual International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia — this was the day that the WHO announced that it would no longer consider homosexuality to be a mental disorder and would be removing it from the International Classification of Diseases. The decision has allowed for greater steps to be taken toward equality in intervening years while also setting a precedent for the policy and practice of the WHO when it comes to other aspects of sexuality and sexual identity.

Winnie Mandela's conviction for involvement in kidnapping and murder, 1991

The 1990s also represented a decisive period in the challenging of apartheid in South Africa, a systematic policy of racial segregation and the withholding of voting rights for Black citizens that existed in the country from 1948 onward. Challenges against the dominant National Party — supporters of segregation — and the African National Congress (ANC) stepped up between 1987 and 1993. Prominent ANC leaders, including Nelson Mandela, were freed from prison.

A similarly iconic presence in the ranks of the ANC was Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, the wife of Nelson, who passed away in 2018. "Mama Winnie" is a hero to South Africans, but there is a mark on her reputation to this day, according to The Mail & Guardian. In 1991, Madikizela-Mandela was found guilty of involvement in the kidnapping and assault of a 14-year-old Moeketsi "Stompie" Seipei, an activist who was later murdered by Winnie's bodyguards as a suspected informant. She was given a six-year prison sentence, which was reduced to a two-year suspended sentence on appeal.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up in the aftermath of apartheid, however, revealed the extent to which disinformation spread in attempts to smear the ANC, and although it may have been Madikizela-Mandela's labeling of Seipei as an informant that led to his death, her own culpability in the death is questionable. The mother of Seipei says she has forgiven Madikizela-Mandela for any involvement and was present at her funeral in 2018.

France agrees to stop testing nuclear weapons, then detonates one, 1995

Though the fall of the Berlin Wall appeared to signal the end of the Cold War that had been a constant source of background anxiety for the generations who'd grown up since World War II, the Atomic Age was far from over. Activists and concerned politicians were attempting, at the start of the 1990s, scale down the use of nuclear warheads as deterrents, which had become a common tactic for many developed nations around the world.

In 1991, France finally agreed to sign the "1968 pact," which, according to The New York Times, had already been signed by the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, and 139 other countries in an effort to limit the use of nuclear weapons. For 23 years, France had been conspicuously absent from the list of signatories, so their eventual agreement was considered a coup by anti-nuclear campaigners. However, in September 1995, France, under the leadership of President Jacques Chirac, began a series of nuclear tests in the South Pacific. The response around the world was one of collective outrage.

In January 1996, after a final explosion that was six times more powerful than the atomic bomb which was detonated over Nagasaki in 1945, Chirac signaled that France was ready to cease nuclear testing and commit to the disarmament of nuclear weapons.

Ireland ends ban on divorce, 1995

Referenda have been responsible for deciding the outcomes of some important political debates around the world in recent years. In 1990s Ireland, the subject of divorce was the hot topic of the day and had been debated fiercely throughout the country for more than a decade. In 1986, the Irish went to the polls for the polls to decide whether married couples could legally be granted a divorce in Ireland for the first time. According to RTE, the "no" camp won a massive victory, beating "yes" by more than a 25-percent margin.

In the 1990s, the subject refused to die down. Another referendum was held, with both sides equally as adamant and aggressive in their arguments as the last time. The Catholic Church and anti-divorce campaigners had the word of God on their side while also arguing that divorce would mean a greater number of broken homes and chaos in terms of housing and property law. The "yes" side warned that such rules were outdated and that nearly 80,000 families were stuck in broken marriages that were a far cry from the Christian ideal they had originally been promised. The Irish taoiseach, John Bruton, claimed it was vital that the motion be passed to protect Ireland's progressive international image.

This time, Ireland voted in favor of ending the ban, but the margin was painfully slim, with just 50.28 percent voting "yes."

The U.S., U.K., and France agree to freeze Nazi gold assets, 1997

According to a reported from the U.S. Department of State published in 1997, the time had come to deal with what it describes as "one of the greatest thefts by a government in history."

During World War II, it says that Nazi Germany stole an estimated $580 million worth of gold, which, in the '90s, was worth around $5.6 billion. As well as numerous other assets and items, the objects were stolen from both governments and civilians that Nazi Germany had overrun and "from Jewish and non-Jewish victims of the Nazis alike, including Jews murdered in extermination camps, from whom everything was taken down to the gold fillings of their teeth."

By 1997, $68 million of these stolen assets were in the Federal Reserve Bank in New York and the Bank of England, where they had been slowly used to offer restitution to European nations since being handed over to the Allies by Sweden, Switzerland, and other nations after the liberation of Europe in 1945.

However, an appeal by the World Jewish Congress arguing that these assets were, in part, privately owned possessions convinced the Clinton administration that the distribution of assets should be frozen and the remainder put toward the foundation of a fund to benefit Holocaust survivors.

Anarchy in Albania after pyramid scheme chaos, 1996-7

The internet age is rife with scams, swindles, and snake oil salesmen, all looking to make a quick buck at someone else's expense. But the 1990s had its own share of exploitative schemes, which sometimes had disastrous consequences on a surprisingly large scale.

According to The Washington Post, the country of Albania had plenty of problems back in the 1990s. The nation had spent 50 years cut off from the world by a tyrannical regime and was officially the poorest country in Europe. A living wage was considered to be $60 a month, and the country still depended on horses and carts to meet many of its transportation needs. Unfortunately, desperation means we are easily exploited.

A series of pyramid schemes emerged, which, to much of the financially untrained population, seemed like offers that were too good to be true. At its peak, it is estimated that more than two thirds of the Albanian population was involved in a scheme. And sadly, when these crashed, pandemonium ensued. There was a huge amount of sustained rioting and violence in the streets, in which more than 2,000 Albanians lost their lives before order could be restored to the country.

The Gianni Versace murder, 1997

There were many shocking deaths that made headlines in 1997, often in circumstances that were pored over by the press for months, if not years. The murder of Gianni Versace made headlines around the world. Since then, the fashion empire that he founded and made a household name has been in the hands of his brother Santo and sister Donnatella, meaning that, though we know the Versace name, the story of Gianni's death may be unfamiliar to many of us.

On July 15, 1997, Versace was shot at point-blank range outside his Florida home by 27-year-old serial killer Andrew Cunanan, according to Time. The designer, who was 50 at the time of his death, was the last in a series of five victims Cunanan had murdered between April and July of that year. Cunanan himself was found dead eight days later on a luxury boat not far from the scene of his final killing.

A motive has never been ascertained, though the press at the time concocted several lurid theories, including the idea that the spree was the result of Cunanan being diagnosed as HIV-positive. An autopsy proved that this was not the case. Some outlets have reported that Versace and Cunanan were known to each other, having met in San Fransisco as early as 1990, but the exact nature of their relationship remains a mystery, with many pointing to Cunanan having delusions of grandeur that may have inflated his sense of connection with Versace.

The launch of the first commercial spy satellite, 1997

In December 1997, Earthwatch Inc., a tech company based in Longmont, Colorado, saw their model for a commercial spy craft launched into space from Russia on the nose of a Russian commercial rocket, according to The New York Times. The event signaled the end of what the paper described as the "monopoly" on satellite surveillance, which, until then, had been the preserve of governments in a handful of developed countries. For the first time, this meant that anyone willing to pay for the service of viewing the Earth from space could do so — which brought with it a whole host of military and security issues of its own.

As always, though, the developers were keen to downplay the fact that their technology rivaled current military technology in the sharpness of its images and its potential impact on the privacy of the population of the entire planet. According to a contemporary article by William J. Broad, the company instead highlighted the advances this could mean for such areas as cartography, disaster relief, law enforcement, and urban planning. Today, commercial satellites are visible throughout the night sky.

The Cavalese cable car disaster, 1998

As noted by The Independent, a ride in a cable car while skiing rarely ends in disaster, as scary as the heights might sometimes be. In the case of the small Italian town of Cavalese on February 3, 1998, one sedate journey came to an appalling end, claiming the lives of 20 people.

The area of the Dolomites in which Cavalese is situated had long been used as a military training site for US Air Force fighter pilots, who exploited the rocky landscape to execute drills and perform hairpin maneuvers which replicated the conditions of actual aerial combat. Thirty-year-old Richard Ashby was piloting an outdated military plane known as an EA-4B Prowler along with his navigator and two crew when the plane took a dangerously low flight path of only 300 feet among the hills of the town. During the maneuver, the right wing of the craft severed the two-inch-thick cable of a slow-moving cable car, sending its 20 occupants plummeting 250 feet to the ground.

None survived. The inquiry that followed absolved the crew of blame, with Ashby dodging manslaughter charges in 1999. The U.S. government reimbursed the $60,000 that the Italian government had paid each grieving family for the disaster, adding an extra $5,000 for the burial and necessary repatriation of each of the victims. Today, many of the relatives of those who perished are still seeking justice for what happened.

NASA's loss of the millennium, 1999

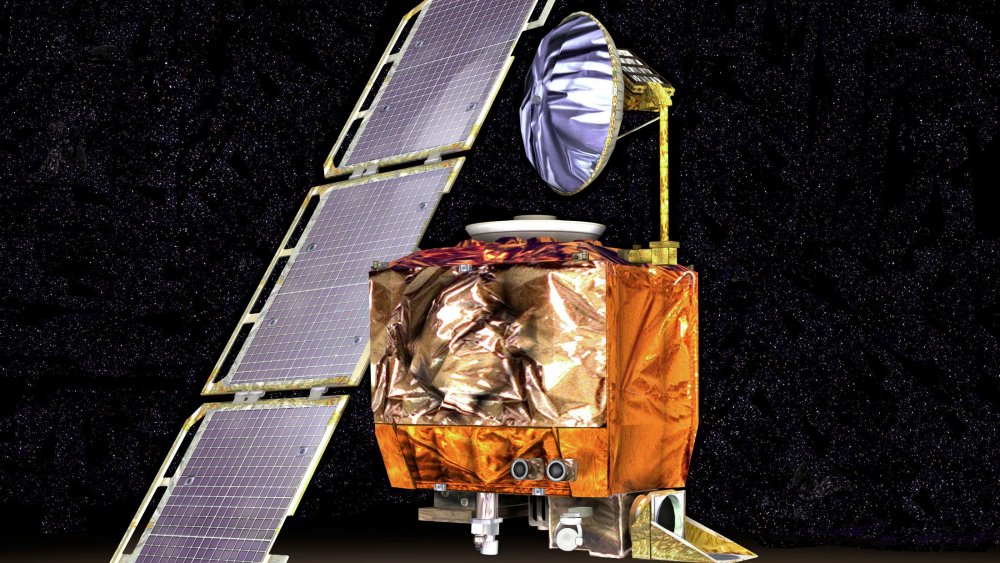

Back in the '90s, nations still dreamed of space travel and exploration, even if it didn't quite capture the imaginations of the general public as it had during the Space Race and the Moon landings. One incident, however, brought NASA back into the public eye just before the turn of the millennium — and it wasn't quite for the reasons that the future-facing times would have expected. At the end of a busy decade for NASA, a simple mathematical equation ended up costing the space agency $125 million in lost assets. And it came down to the difference between imperial and metric measures.

According to Simscale, the Mars Climate Orbiter was a 338-kilogram space probe tasked with exploring the Red Planet, its atmosphere, and changes on the planet's surface. It was also meant to provide communication with a probe that had been sent out the previous year: the Mars Polar Lander.

However, a frustratingly common mistake ensured the ruination of a bold and ambitious project. As CNN reported, the craft's engineering team had been using English imperial measurements in their calculations, while NASA had been working in metric units to describe the trajectory of the craft. The result? The craft burned up, taking hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of tech — and billions of dollars of research – with it.