12 Details About Cleopatra And Julius Caesar's Relationship

Cleopatra VII Philopator was one of Egypt's most notable queens, remembered for her intelligence, charisma, boldness, and willingness to flout societal conventions in order to pursue personal and political goals. Julius Caesar, dictator of the Roman Republic, was one of the key figures in the oft-chronicled downfall of the republic and rise of the Roman Empire. Therefore, it makes sense that the story of their relationship has captivated historians, artists, writers, and the collective public imagination alike.

Cleopatra and Caesar met in the summer of 48 BC, when Cleopatra was caught in a tempestuous struggle for power with her brother and Caesar had just moved to Alexandria. They were lovers until the Ides of March in 44 BC, when Caesar was tragically murdered. Their legacy has since been kept alive through countless primary source documents, biographies, and creative works.

Curious about the details of this star-crossed affair? Read on to learn the story of the two rulers' liaison.

Cleopatra and Caesar's affair was politically motivated

Before meeting Caesar, Cleopatra was in a difficult spot politically. As Amy Crawford explains in her Smithsonian Magazine article "Who Was Cleopatra?," her father had named both her and her teenage brother, Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII, as co-rulers in his will. However, Cleopatra had tried to make herself the sole sovereign of the kingdom circa 49 BC — and as retaliation, Ptolemy had driven her from their palace in Alexandria.

Caesar entered the picture in 48 BC, when he arrived in Alexandria while pursuing a military enemy. Egypt and Rome had long been allies, and Caesar figured that it might be in the best interest to arbitrate between the siblings. He summoned Cleopatra and Ptolemy to a conference in Alexandria so that they could settle their dispute. Yet Ptolemy was not ready to have a civil discussion with his sister. He called upon his military forces to prevent her from entering the city, much to her dismay.

Cleopatra knew that calling upon Caesar's help could be the key to regaining her power. Therefore, she began plotting a way to secure an audience with him and gain his trust and support. Their meeting ended up being the start of a lengthy affair.

The story of Cleopatra's initial meeting with Caesar is partly myth

As outlined in Amy Crawford's Smithsonian article, it is often said that Cleopatra came up with a scheme to sneak herself into the palace where Caesar was staying by hiding inside a rolled-up carpet. After wrapping her up, her servant Apollodoros presented the carpet to Caesar. Then Cleopatra revealed herself and explained her situation to the dictator. According to Egyptology scholar Alexander McDaniel, this myth is accurate to a text written by Greek philosopher and biographer Plutarch, with one key exception: Plutarch wrote that Cleopatra disguised herself with a large sack. Nevertheless, several paintings and films have perpetuated Cleopatra's association with the image of the carpet over the years.

In a blog post called "Cleopatra and the Carpet Myth," art history professor Monica Bowen traces the history of this misunderstanding. In 1937, she writes, Cecil B. DeMille's Cleopatra showed Claudette Colbert unfurled from a rug. Twenty-six years later, the myth was depicted once more in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's epic Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth Taylor.

Cleopatra and Caesar were both married during their affair

Cleopatra and Caesar's relationship wasn't simply notorious because of the two rulers' political status. It was also shocking because both parties were married throughout the liaison. As explained in an article by the Altes Museum, Cleopatra was married to her "rebellious brother" and co-regent Ptolemy XIII when she and Caesar first became involved. When Ptolemy XIII died in 47 BC, Cleopatra married her younger brother, Ptolemy XIV, to ensure that her reign was still legitimized. At this point, she had just become pregnant with Caesar's child. Caesar, meanwhile, was married to a woman named Calpurnia — his fourth wife. According to Egyptology scholar Jenny Hill in her essay "Cleopatra and Julius Caesar," Calpurnia was the daughter of an important Roman family. She was a meek, submissive, "proper" woman, in stark contrast to the bold Cleopatra.

In the biography Cleopatra: The Last Pharaoh, Prudence J. Jones writes that Cleopatra was not the general's only mistress. Unfortunately for Calpurnia, Caesar had multiple affairs with multiple women, and his status as a philanderer was known throughout Rome. Of course, Cleopatra held a special position among his many lovers: He was so enamored with her that he granted her a house across from his own.

The Romans weren't fond of Cleopatra

Today, Cleopatra is often remembered as a subversive figure, known for flouting the rules society set for women. According to Prudence J. Jones, this is how she appeared to the Romans during her lifetime, as well. The Romans, who were largely proud of their republic, were already suspicious of monarchs when Cleopatra and Caesar became involved — and the Greek-Egyptian Cleopatra was an emblem of both "the kingdoms that resulted from Alexander's empire" and "the Egyptian pharaohs." Therefore, they were predisposed to dislike her as soon as she appeared on the scene. Her gender added insult to injury. The Romans believed that women should support their husbands' political ambitions, not participate in public life themselves. They also valued simplicity, and Cleopatra's lavish lifestyle was anything but simple. Considering all this, they were largely taken aback by Cleopatra's reign and extravagant ways.

Jenny Hill writes that Cleopatra and Caesar's relationship was looked down upon by the Roman senate, who admired Calpurnia for her demure and submissive demeanor and detested Cleopatra for interloping. Cleopatra was especially hated by the orator Cicero, who believed that women were not intelligent enough to hold positions of power and despised Cleopatra's influence on Caesar.

Cleopatra and Caesar went on a cruise of the Nile together

Cleopatra and Caesar made no secret of their association. While they were involved, they went on a tour of the Nile together in a navis thalamegos, or extremely large barge. According to ancient history scholar T.W. Hillard in his essay "The Nile Cruise of Cleopatra and Caesar," this ship would have been a "houseboat/cabin-cruiser" the size of "half a stadium," with dozens of rooms and numerous luxuries — perfectly fit for a queen and her Roman general lover. Not much is known about the voyage due to a lack of sources. However, ancient Roman historians Suetonius and Appian provide some context. Suetonius reports that the two intended to sail all the way to Ethiopia, but Caesar's troops refused to follow him all that way. Appian recounts that Caesar "generally enjoyed himself" in Cleopatra's company.

Prudence J. Jones writes that the voyage was far more than a getaway for the two lovers. Rather, it was a means of establishing Cleopatra's power. Recall that Cleopatra did not reign over Egypt alone: She was a co-ruler with her brother. The cruise would have shown that she was the more important figure in this partnership. It would have also introduced Cleopatra to Egyptians living outside Alexandra and made her ties with Caesar clear.

Cleopatra and Caesar had a son

Cleopatra and Caesar's affair resulted in a son born circa 47 BC. As detailed by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, his name was officially Ptolemy XV Caesar, but he went by multiple monikers. He was also known as "Theos Philopator Philometor," or "the Father-loving Mother-loving God." However, he was most commonly referred to by his nickname "Caesarion," or "Little Caesar."

Cleopatra was clear about Caesarion's paternity: He was nothing less than the son of the dictator of the Roman Republic. Yet Caesar maintained ambiguity on the topic. According to Suetonius, upon hearing of Caesarion's existence, Caesar summoned Cleopatra to Rome and showered her with "high honours and rich gifts." He then allowed Cleopatra to give his name to the child. However, he never explicitly announced himself as the boy's father. Caesarion's illegitimacy did not affect his upbringing much, in that Egyptians recognized him as Cleopatra's successor without a challenge. He was raised in the culturally Hellenistic city of Alexandria, where he was tutored by a Greek scholar named Rhodon.

Caesarion came to power as Cleopatra's co-ruler in 44 BC, after her brother Ptolemy XIV's sudden death (which some thought was a murder to bring her son onto the throne). He reigned beside her until August 12, 30 BC, when she died by suicide. Caesarion was the sole ruler of the kingdom for mere weeks. Then he was executed by Octavian, Caesar's grand-nephew and Mark Antony's fellow triumvir, who was likely jealous of his connection to Caesar.

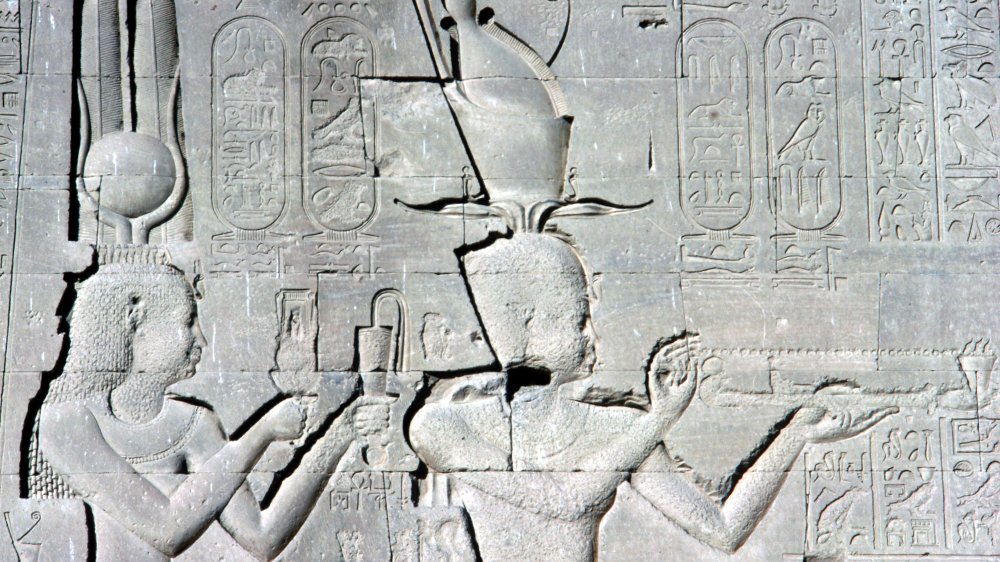

Caesar built a controversial statue in Cleopatra's likeness

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, in 46 BC, Caesar dedicated a temple to the goddess Venus Genetrix. Venus Genetrix was held in high esteem by the Roman people. She was the goddess of marriage and paternity. Caesar also claimed her as his divine ancestor. Therefore, it was particularly shocking when he unveiled a statue of Cleopatra at the temple.

Jenny Hill notes that it was common for the pharaohs of the Ptolemaic kingdom to have statues of themselves commissioned and placed beside statues of the gods. However, Caesar giving Cleopatra a statue in a Roman temple was unprecedented, as it suggested that the Roman people were supposed to see her as divine — especially since the statue gave her aspects of both Venus and her Egyptian counterpart Isis. The statue was also controversial because Venus Genetrix was associated with marriage, so Caesar drawing a link between her and Cleopatra could be interpreted as a metaphorical slap in the face to Calpurnia.

Yet Antony Kamm points out in his book Julius Caesar: A Life that it may well have had genuine religious significance in addition to being a tribute to Caesar's lover. There was a long-standing literary tradition of associating Isis with Venus and their Greek counterpart Aphrodite in the ancient world. By placing a statue of Greek-Egyptian queen Cleopatra in a Roman temple and representing her as the amalgamation of these goddesses, Caesar would have been nodding toward history.

Their relationship lasted until Caesar's funeral

Cleopatra's affair with Caesar lasted until the Ides of March, or March 15, 44 BC, when Caesar was famously assassinated by his friend Marcus Junius Brutus, among others. As explained by Jenny Hill in her essay, his murder created quite the uproar in Rome. Several eyewitnesses to Caesar's funeral said that his pyre was set aflame by two "divine forms." Some theorists believe that Cleopatra hired two actors to dress as Castor and Pollux, two immortal twins from Roman mythos, to appear at the ceremony and reinforce the idea that Caesar was divine.

Cleopatra was stricken with immense grief after Caesar's funeral. According to a spiteful, gossipy letter from Cicero, she suffered a miscarriage in the throes of mourning. Yet she couldn't stay in Rome while healing: There was reason to believe that Caesarion might be in danger, as well. Wanting to protect him, she fled back to Egypt.

Cleopatra and Caesar's affair influenced the creation of the Julian calendar

Cleopatra had a profound influence on Roman culture during her dalliance with Caesar. In fact, according to Jenny Hill, she might have even impacted the way the Romans measured the calendar year — and in turn, the way humans would keep time for years to come. While Cleopatra and Caesar were involved, Hill states, Cleopatra's astronomers helped Caesar revise the Roman calendar system. This resulted in the Julian calendar, which is the basis of the Gregorian calendar, which we use today.

In an article for The Pioneer, Priyardashi Dutta explains the nuances of the great calendar alteration. The Roman calendar was based on the lunar year and consisted of 354 days — 11 days fewer than the solar calendar. Therefore, as time passed, Rome's seasons eventually began to occur out of sync with its months. By the time Caesar was appointed dictator, Dutta explains, "the calendar had fallen more than two months behind the natural year." This error was largely remedied with the creation of the Julian calendar system, which had 365 days and accounted for leap years. (Later on, it would be perfected by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582.)

It is said that Cleopatra wowed Caesar with her wit rather than her physical beauty

In dramatizations of her life, much emphasis has been placed on Cleopatra's physical beauty, to the point where it is often considered her foremost quality. Many modern depictions of her are influenced by her 1963 portrayal by Elizabeth Taylor, who appeared as a vision of delicate glamour in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's epic Cleopatra. However, ancient descriptions of the Egyptian queen paint a more nuanced picture of her appearance.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, it was not necessarily Cleopatra's features that gave her notoriety but rather her charming personality and quick wit. In his Life of Antony, Greek biographer and philosopher Plutarch asserted, "Her actual beauty ... was not so remarkable that none could be compared with her, or that no one could see her without being struck by it, but the contact of her presence ... was irresistible... The character that attended all she said or did was something bewitching."

Plutarch wrote this paragraph in AD 75, more than 100 years after Cleopatra's death in 30 BC. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that he wouldn't have ever looked upon Cleopatra himself: His description would have been based upon information from secondhand sources. Nevertheless, in any case, it is clear that Cleopatra was "more than just a pretty face": She was a clever, confident woman who used her emotional intelligence to influence others.

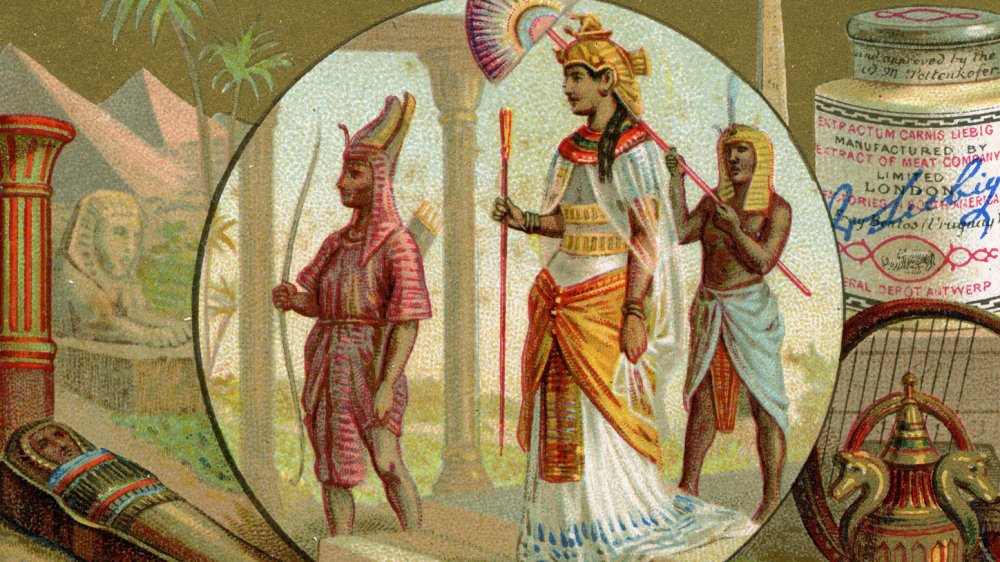

Cleopatra and Caesar's meeting was depicted in a famous painting

As a famous historical figure known for her opulence, Cleopatra has made her fair share of appearances in art. In 1866, her meeting with Caesar was depicted in a painting (pictured above), aptly titled Caesar and Cleopatra, by French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme. As detailed by the American Egyptomania project at George Mason University, Gérôme was internationally renowned, with "students from all over Europe and America." Many of his works are now considered examples of Orientalism: the stereotypical depiction of the Eastern world as a land of seductive otherness, with an emphasis on "exoticized, eroticized figures."

Caesar and Cleopatra is no exception. Cleopatra stares at Caesar intently, wearing nothing but a harness that reveals her breasts and a sheer skirt that reveals the curves of her idealized body. At her feet, Apollodoros holds the rug that was used to smuggle her into the palace. Caesar looks upon her with a shocked demeanor, clothed in a red robe that connotes his majesty and power. His associates, too, have their heads turned in surprise.

Caesar and Cleopatra was created as part of the trend known as Egyptomania: the wave of renewed Western interest in ancient Egypt that occurred in the 19th century. Gérôme's audience would have instantly recognized the image of Cleopatra in his painting, if not the legendary encounter being depicted.

A movie was made about Cleopatra and Caesar

Cleopatra's life was replete with drama, so it makes sense that writers would be drawn to it. One such writer is famous playwright George Bernard Shaw, whose 1901 Caesar and Cleopatra chronicles the relationship of the two lovers. Shaw's play emphasized the political motivations that brought the rulers together rather than presenting a starry-eyed view of the affair.

In 1945, Gabriel Pascal, a Hungarian-British producer and director known for adapting Shaw's works, directed a film version of Caesar and Cleopatra. The film starred Tony Award-winning Claude Reins and Vivien Leigh of Gone with the Wind and A Streetcar Named Desire fame. Shot in Technicolor, the epic is known for its beautiful visuals as well as its nuanced take on the interactions of two of history's most famous rulers. According to Criterion, at the time of its production, it was the most expensive British film ever made. Pascal paid an immense amount of attention to detail, even going so far as to import real Egyptian sand.