The Adventures Of Dr. Livingstone Explained

During the 19th century, when the British Empire was very nearly at its height and much of the world was still a mystery to Europeans, explorers were superheroes. They marched through unknown (to them) continents, stoically enduring hardships while claiming new land and glory for their queen, Victoria. According to Livingstone Online, British explorers were well-known and well-financed in their quest to reach every corner of the empire.

Today, that legacy has become much more complicated. Too many explorers were invested in holding up a colonial system that abused native peoples and glorified a single, homogeneous way of life. Postcolonial theory, defined by Oxford Research Encyclopedias as a critical take on the long-standing effects of colonial structures, has formed the basis for this reconsideration.

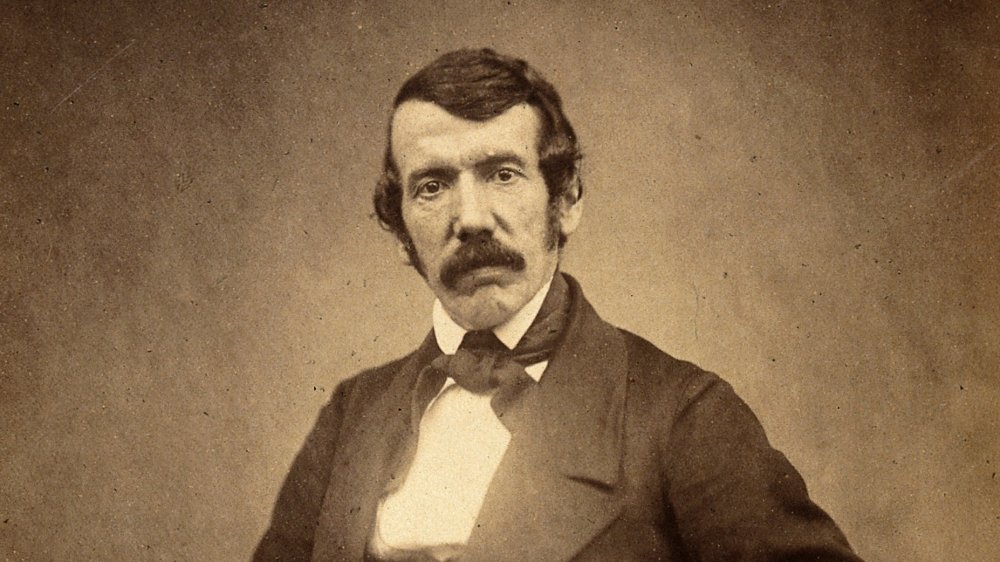

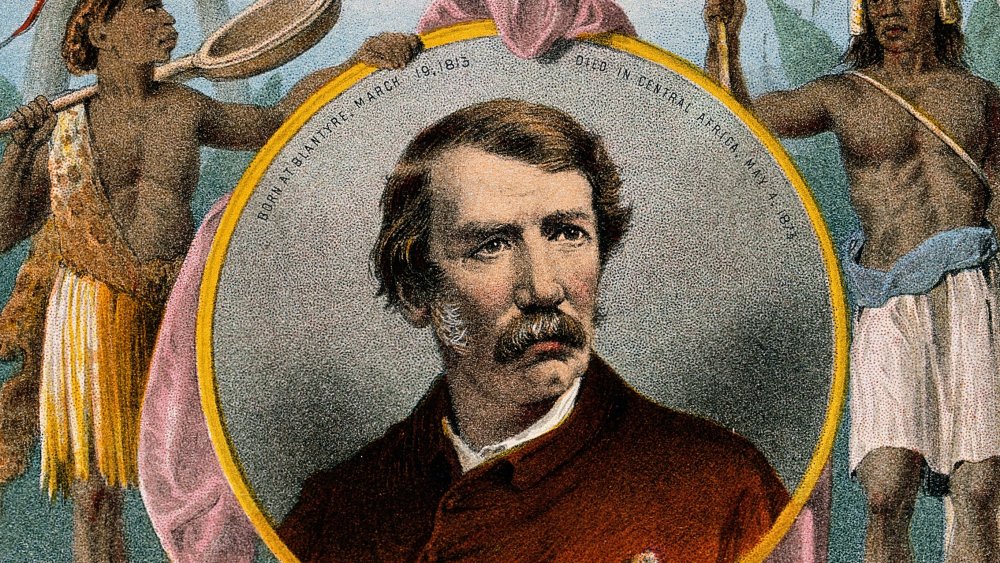

David Livingstone sits at the intersection of these two narratives. He very clearly profited off a colonial system that financed his expeditions. He was a missionary intent on changing Africans' religions to Protestant Christianity, with the underlying assumption that their original beliefs were a one-way ticket to Hell. Yet, he also crusaded for genuine good. Livingstone was horrified by the slave trade, reports New Scientist. Over his entire career, in his own way, he tried to find a solution that would abolish slavery and allow African nations to one day independently govern themselves. He genuinely believed in his convictions, though he could be led astray or distracted by finances. Livingstone was, in short, a complex man who left an outsized mark on history.

David Livingstone had a rough start

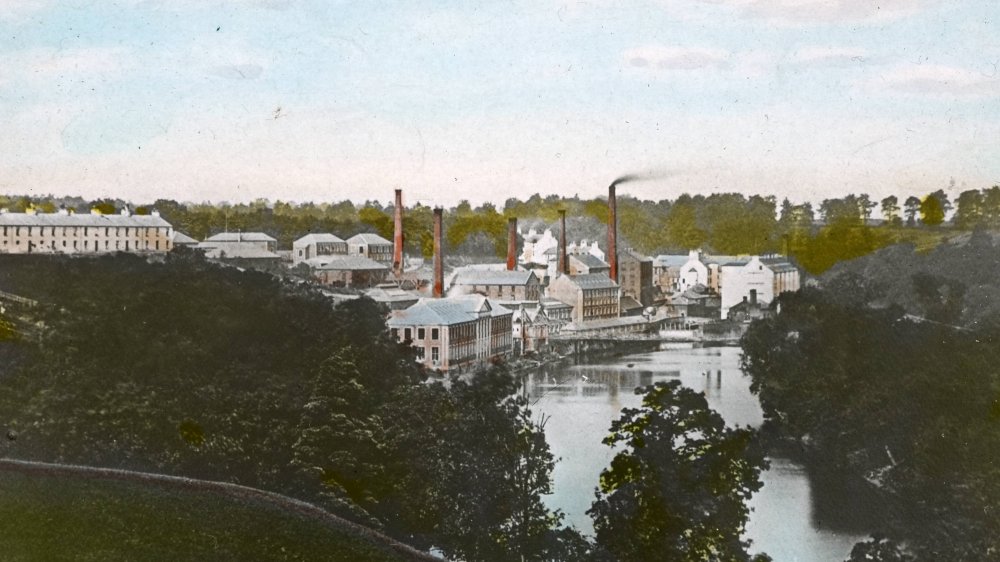

Born in 1813 in Blantyre, Scotland, David Livingstone and his many siblings grew up in a single room in a ramshackle tenement, says Biography. It was an inauspicious start for the young boy, who would later grow to be one of the most famous explorers of his time.

The future Dr. Livingstone was given a rudimentary education as a young child and then quickly pushed into work at Blantyre's cotton mill, according to Livingstone Online. For the time, and especially for poor families that needed as much income as they could get, this was not unprecedented.

Young David was different. From an early age, he showed an intense appetite for knowledge, studying during his infrequent off hours in the evenings and on weekends. He was also uniquely driven. Coming from a religious family, it's no surprise that he wanted to be a missionary. Yet, he also realized that to achieve that goal, he would need to distinguish himself. His plan was to become a doctor, which he believed would open up the right avenues to spread the Word of God across the world. He began his studies in his early twenties, first in Scotland and then completing his degree further south, in England.

Dr. Livingstone was deeply religious

After earning his medical degree, says Biography, Dr. Livingstone was trained by the London Missionary Society and dispatched as a "medical missionary" to Africa in 1841. He landed in Cape Town, South Africa.

He worked with Robert Moffat, a fellow missionary who would also become his father-in-law when David wed Mary Moffat, says Boston University. For a time, Mary and their children stayed in Africa, but David soon determined that he needed to go further into the continent to spread his message. His young family traveled back to Scotland while Livingstone began to travel, first north to Zambia, then west to Angola. At one point, he decided that this wasn't good enough, so he turned east and walked all the way across Africa to Mozambique, on the eastern coast.

His book about these treks, Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, was published in 1857 and became a hit. People hailed Livingstone as a hero, and the book sales didn't hurt, either.

Over the course of his many years on the continent, he's only recorded as having converted one man, a chief named Sechele, says the BBC. Livingstone himself abandoned Sechele as a lost cause, as the man continued to employ traditional practices like rainmaking and polygamy. Yet, Sechele was a vastly intelligent leader who quickly became fluent in English, translated the Bible into the Tswana language, and arguably did more to spread Christianity than Livingstone himself did in either's lifetime.

Dr. Livingstone was an abolitionist

While the Atlantic slave trade had been banned by the United States and Great Britain by 1807, says History, it was far from done when Dr. Livingstone arrived in Africa. Other nations, like Brazil, continued participating in the slave trade until the 1860s, shipping captured Africans across the ocean. This generated great upheaval throughout the continent, as captives were transported by both foreign traders and other Africans on grueling marches to ports.

Livingstone witnessed the effects of this trade directly. As he made his way to the Portuguese colony of Mozambique, he saw these forced marches. According to the Smithsonian, traders frequently passed the slaves on to Swahili and Arab merchants, who would then distribute the human chattel throughout the Middle East.

Livingstone was appalled by not only the effect of the trade upon captive people but also upon those who were trading them. As he wrote in Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, "No one can understand the effect of the unutterable meanness of the slave-system on the minds of [the traders]. Fraud becomes as natural to them as 'paying one's way' is to the rest of mankind."

The manner in which Livingstone talked about the people of Africa, including these traders, holds an undercurrent of paternalism and colonialist tendencies that has occupied scholars for many years. Yet, it is obvious that he was no friend to the traumatic slave trade that had been ravaging Africa.

Dr. Livingstone still loved the empire

Dr. Livingstone was complicated. He pushed back against the slave trade, but he did so in a way that favored European takeover. Then again, argues Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, it might be more accurate to understand Livingstone's efforts to "civilize" the continent as an attempt to bolster a future independent Africa.

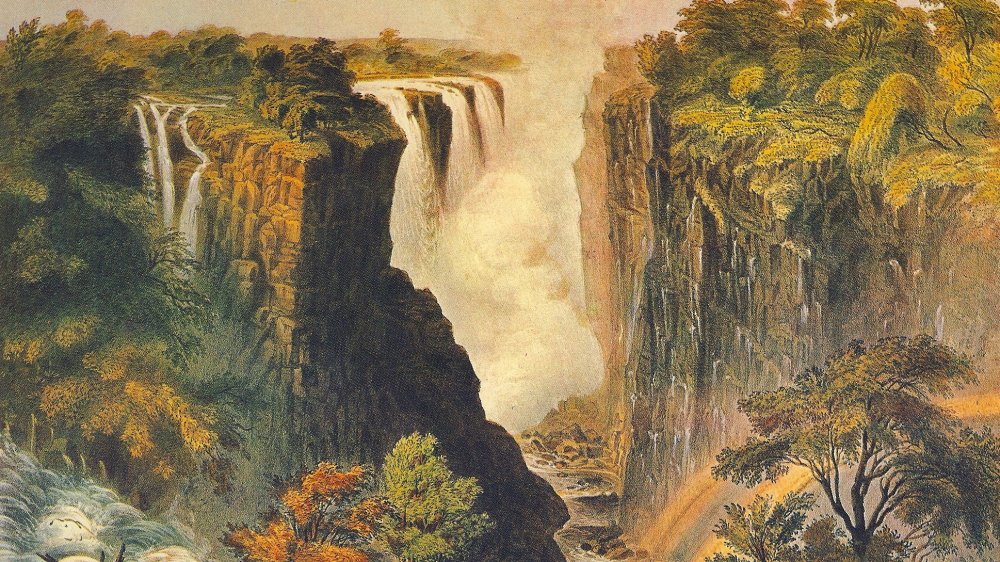

At the same time, it's clear that Livingstone was part of an imperialist system. He was a British subject during the reign of Queen Victoria, when the already large British Empire was still growing. His proposed alternative to the slave trade was to bolster commerce with British goods and British oversight, at least initially, says the Smithsonian. He also wasn't afraid to rename landmarks in favor of the monarch. Livingstone is widely acknowledged as the first European to see what he called Victoria Falls, a waterfall on the Zambezi River on the modern border between Zambia and Zimbabwe. "No one can imagine the beauty of the view from anything witnessed in England," he wrote in Missionary Travels.

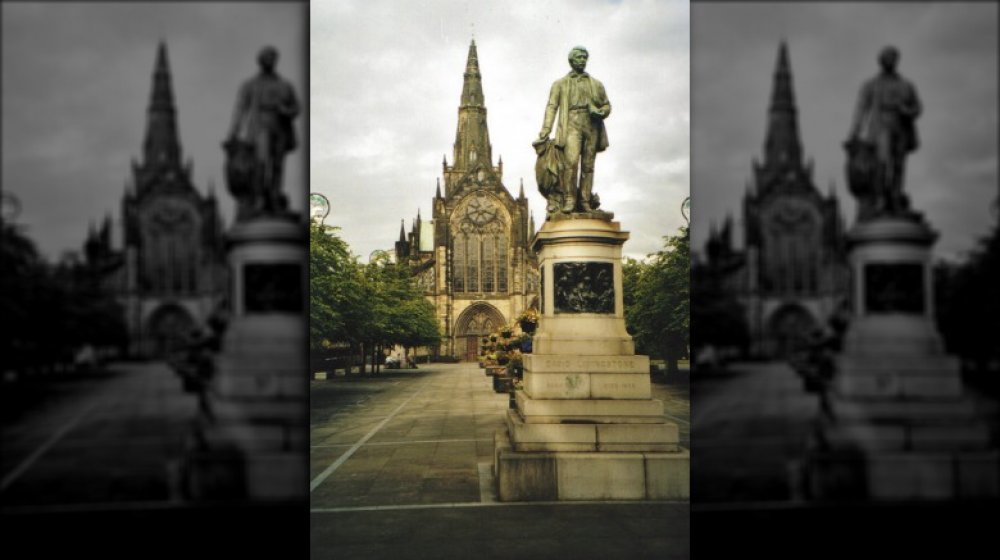

The afterlife of David Livingstone further complicates matters. Once he had passed, the story of his travels across Africa were memorialized and mythologized for decades, says Livingstone Online. This narrative may have done more to bolster the idea of the British Empire than the man himself was ever inclined to do. As the empire fell out of favor and postcolonialism became part of historical studies, so, too, did Livingstone's story change.

Dr. Livingstone's work as an explorer made him famous

David Livingstone initially traveled to Africa as a missionary, but his ambitions would soon complicate his role on the continent. By 1842, he had already traveled further northward from Kuruman, South Africa, says Britannica, in an attempt to bring his missionary message to more people. By the end of the decade, he was already gaining a reputation as an explorer. He had acted as the surveyor on an expedition that claimed the first European sighting of Lake Ngami in August 1849.

His travels in the 1850s, which he would turn into his first published book, Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, were ostensibly about missionary work. His particular tack was to find better trade routes, especially ones that could be turned into roads. Better commerce, he reasoned, would provide a good alternative to the horrifying slave trade. Nicely maintained roads would also make it easier to establish Christian missions, too. It would also allow him and any other travelers to avoid the Boers, Dutch-descended people who had made Livingstone's family abandon their Kolobeng Mission in 1852, according to Missionary Travels.

Eventually, the drama of Livingstone's explorations proved compelling. Sales of Missionary Travels made his family comfortable, while the Royal Geographic Society awarded him money and recognition, says the biography Livingstone.

People went gaga over Dr. Livingstone's adventure books

Just like today, readers of the 19th century were ready to gobble up all the exciting travel narratives they could find. Per The Guardian, the thrills of exploration and the very real danger faced by explorers were compelling to those stuck back in more comfortable situations at home. It also allowed them to leave their mundane, sometimes tough lives. Thomas Cooper, a 19th-century shoemaker quoted in the article, says that the books took him away from "the vulgar world of circumstances in which I lived bodily."

Though readers clamored for new adventure tales, Dr. Livingstone had to be persuaded into writing a book, says Livingstone Online. Roderick Murchison, president of the Royal Geographical Society that had already recognized Livingstone for his earlier work, connected him with publisher John Murray. Eager to get Livingstone on board, Murray promised to pay for all the publishing costs, provide illustrations, and take only a third of the profits, as opposed to the usual half.

Even though Livingstone clearly understood that his field diaries would need to be transformed into something that appealed to the public and pushed his missionary message, he didn't take kindly to edits. In a letter to Murray written on May 30, 1857, he complained that revisions had "emasculated" his work, making it too weak and soft to really hold up his manly missionary zeal.

In his later years, Dr. Livingstone was broke

Though Missionary Travels earned a good income and renown for Dr. Livingstone, it didn't last. A disastrous expedition up the Zambezi River from 1858 to 1864 devastated Livingstone's bank account and put his family's future in jeopardy.

The Zambezi Expedition, says Livingstone Online, was a terrible mess. Livingstone still wanted to encourage commerce that wouldn't require the slave trade, but, thanks to Missionary Travels, he was now a national hero who could command serious financial support. As a result, the British government granted him a whopping £5,000 and a new title as British consul. With a new team, Livingstone was tasked with exploring the Zambezi River as a possible trade route for British vessels.

Things went poorly, reports JSTOR. No one in the group seemed to get along, and many ended up leaving or dismissed by Livingstone. Rapids on the river were impossible to pass. Livingstone attempted to go up other rivers, but they proved difficult to navigate, too. Expedition members who hadn't been booted then became ill, and some even died, leading to the recall of the whole affair in 1864. Livingstone returned from the expedition discouraged and light on cash.

Dr. Livingstone tried to find the source of the Nile

If the 1858-1864 expedition to navigate the Zambezi River was a disaster, then Dr. Livingstone's next venture was even worse. But, with depleted funds and a suffering reputation, it could have been that Livingstone felt he had to try anyway. His task? Find the source of the Nile.

The mission came down from Roderick Murchison, president of the Royal Geographic Society, says Livingstone Online. Really, he was supposed to survey the water system of central Africa, but answering the age-old question of from where the Nile sprang forth was a nice bonus that would have improved his standing. He wasn't there yet, though. Livingstone was made a mere "roving consul" and given only £500 in funds, though friends raised an additional £1,000, according to Livingstone.

According to Britannica, Livingstone's crew quickly broke apart, perhaps because Livingstone wasn't an effective leader. Some, afraid of punishment for deserting the famous explorer, reported that he had been killed by raiders. Back in Europe, people began to wonder if he might have passed away for real.

Livingstone, still very much alive but struggling, pressed on. He reached Lake Tanganyika in early 1869 and, by 1871, had gone as far as Nyangwe, a town in what's now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. At that point, Livingstone was the only European known to have traveled that far into Africa. But, he was constantly ill, lacking supplies, and simply an aging man in a harsh environment.

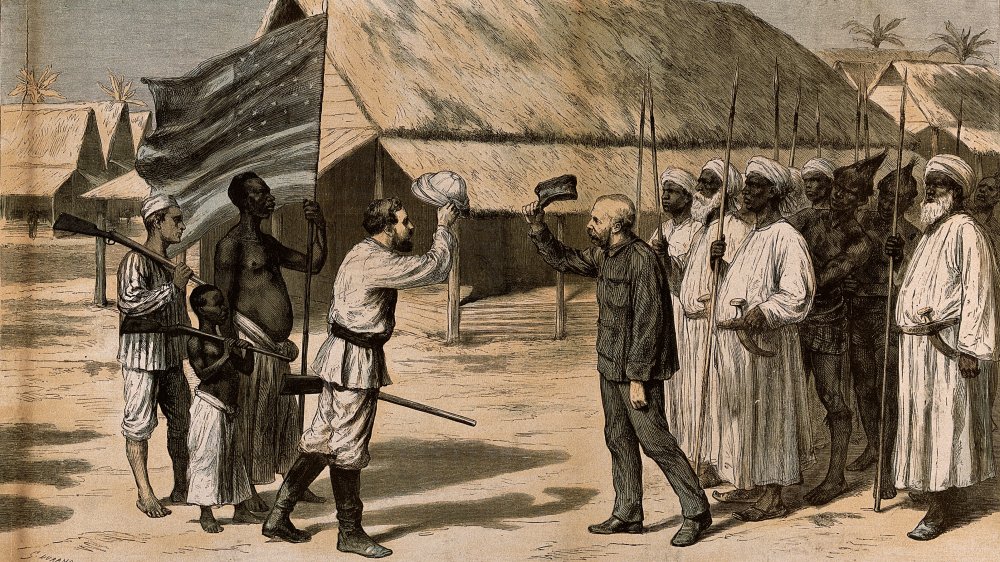

Henry Morton Stanley's famous line was an attempt at humor

With David Livingstone's location unknown, some began to wonder if the famous explorer and missionary had died. Not everyone was convinced, however. Per History, journalist Henry Morton Stanley was sent to find Livingstone in 1869 by the New York Herald. As quoted in Into Africa, Stanley told his editor that "If [Livingstone is] alive, you shall hear what he has to say. If dead, I will find him and bring his bones to you." Nothing, apparently, was going to stop Stanley.

Livingstone was still in the land of the living, though just barely. He was in Ujiji, a village in what's now Tanzania. He had suffered a series of illnesses and setbacks that left him dependent on the hospitality of the Arab traders he had so maligned earlier.

Stanley, upon finally meeting him in 1872, reportedly said, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" It was a joke, considering that they were the only two Europeans for hundreds of miles. Only, there's no real evidence that Stanley uttered the famous line. Stanley: Africa's Greatest Explorer points out the awkward fact that Stanley tore out the pages of his diary that would have provided the best evidence. He may have made up the lines later just to look cool.

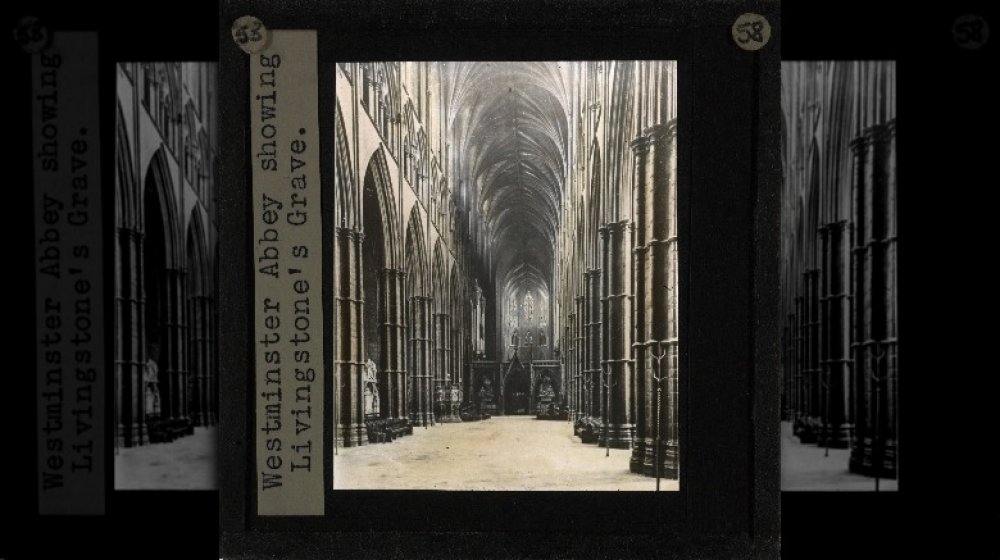

Only part of Dr. Livingstone is buried at Westminster Abbey

Though Henry Morton Stanley, the journalist who "found" Dr. Livingstone, tried to get Livingstone to come back to Europe with him, the older man refused. He never saw Britain again. After years of difficult traveling and poor health, David Livingstone died in 1873, in the small village of Ilala near Lake Bangweulu in Zambia, according to The Explorers. His likely cause of death was a combination of tropical diseases like malaria and dysentery.

His two assistants, Chuma and Susi, understood that Livingstone's remains were to be transported back to Great Britain, but they determined that part of him would stay in Africa. They removed Livingstone's internal organs, burying his heart beneath a nearby tree, variously said to be a baobab or mpundu tree. As reported by Smithsonian Magazine, the rest of what remained of the explorer and missionary was dried with salt and sand, wrapped in cloth, and carried over 1,000 miles back to the coast. Jacob Wainwright, another African man whose diaries gave a firsthand account of Livingstone's end, accompanied the remains back to England.

Upon hearing of Livingstone's death, A.P. Stanley, the dean of Westminster, offered to bury the explorer, says Westminster Abbey. While a funeral had already been held in Africa, a second one was conducted at the Abbey on April 18, 1874.

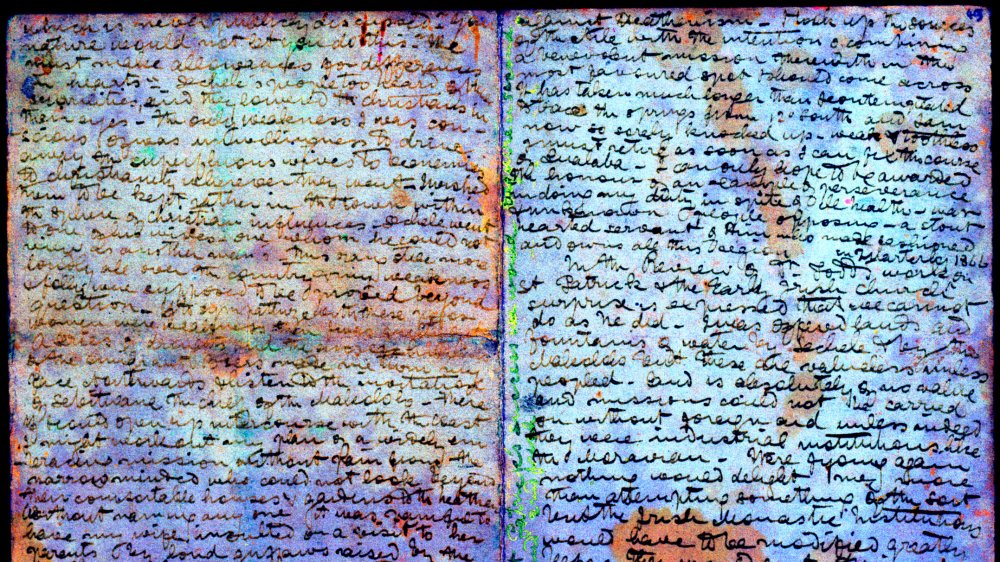

Dr. Livingstone's diaries complicate his legacy

After Dr. Livingstone's death, an account of his final travels was published as The Last Journals of David Livingstone in 1874. Only, this was an interpretation of the written record left behind by Livingstone himself. Given how Livingstone was transformed into a useful legend not long after his death, could this story be a bit too rosy to be true?

For a long time, says Smithsonian Magazine, scholars simply couldn't read a portion of Livingstone's last diaries. Practically stranded in a remote area and dangerously ill, he had been saved by Arab traders. Livingstone began an uncomfortable alliance, where the Arab traders he had fought so hard against provided him with shelter, food, and medicine. He still kept a diary, but, having run out of writing supplies, Livingstone had to improvise. He began scribbling on an old newspaper, using berry juice as ink. Though it worked at the time, the combination of faded botanical ink and newsprint background made deciphering the diaries all but impossible. It was only thanks to advanced imaging technology that these entries finally became legible in the early 21st century.

Their contents reveal a more complicated picture of Livingstone than what had been previously held. Most shockingly, his diaries contain hints that freed slaves allied to Livingstone could have helped commit a massacre, reports CBS. Livingstone may have been so horrified by the violence that he retreated to Ujiji, where Stanley found him soon after.