The Weirdest Etiquette Rules People Used To Follow

The British writer and critic Quentin Crisp once wrote: "Nothing more rapidly inclines a person to go into a monastery than reading a book on etiquette. There are so many trivial ways in which it is possible to commit some social sin." Being British and rather posh, you would expect Crisp to know what he's talking about. But the fact is that etiquette books telling people how they should behave are hugely popular in both Europe and the U.S. — where, historically, etiquette takes its cues from what the bona fide upper-class members of European society are doing. Whole dynasties of etiquette teachers are still active today.

But what is etiquette? One way of describing it is in terms of good manners, that etiquette is made up of the rules society deems necessary to stop us from impinging on other people's lives as they go about their day-to-day business, which sounds like quite a noble purpose when you think about it. Talking with your mouth full, for example, can look gross enough to put other people off their dinner. The etiquette that says it should be avoided serves a social function.

But what about those rules that society has followed that really don't seem to make a whole heap of sense? Here's a look at the changing face of etiquette over the previous centuries, how its purpose changed, and what we might learn about how we approach rules of behavior today.

Sprezzatura -- the birth of hipster cool

"Sprezzatura" is an Italian word which, like "schadenfreude" from the German, doesn't really work in any English translation. The concept is quite well-known in Italy, but we probably all have a sense of what it is.

According to ThoughtCo, the word comes from an etiquette guide written in the 16th century, The Book of the Courtier by Baldassare Castiglione, count of Casatico. Castiglione was an active member of the high-class court of Urbino, and his book was intended as a guide for how courtiers should behave, what they should know and do as hobbies, and also, strangely, the attitude they should strike when going about their business. Castiglione said: "One must avoid affectation and practice in all things a certain sprezzatura, disdain or carelessness, so as to conceal art, and make whatever is done or said appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about it."

The book was highly influential in courts throughout Europe and irreversibly affected how the upper classes presented themselves in company. In fact, this centuries-old etiquette book is considered by many to be the root of what we consider "cool" today, and while we don't openly follow its laws of etiquette, we are probably all familiar with the connection between coolness and a certain effortlessness or aloofness. The concept is still well-known in Italy and is particularly influential in the field of fashion.

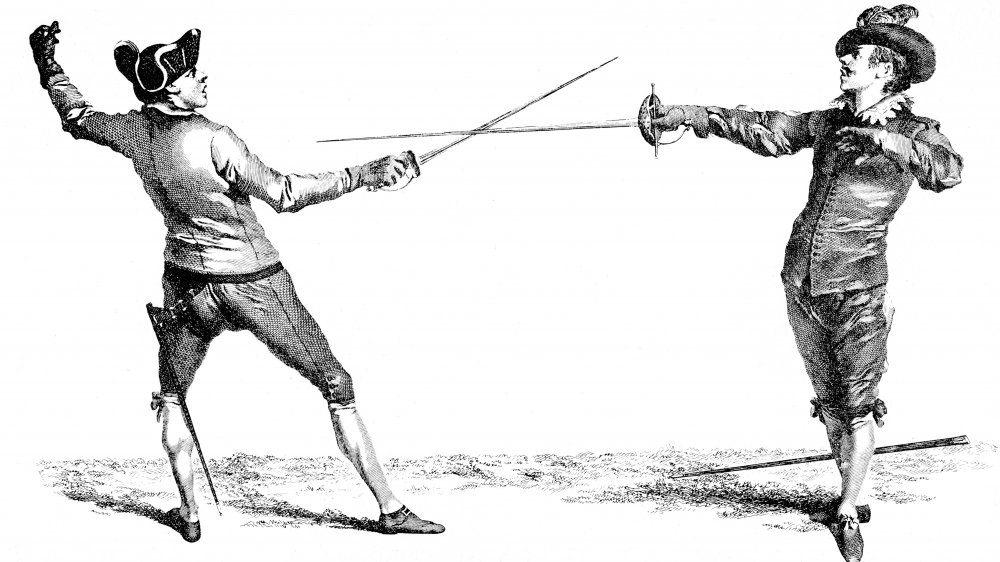

Dueling with decorum

When it comes to etiquette, the rules that we might find hardest to process today are those that govern acts of violence. (Or, maybe not — there are "rules" for war which nations are meant to follow today.)

At around the turn of the 17th century — but with its roots going back much farther than that — the ritual of dueling was still a common occurrence in many European countries, especially in France, where it is estimated that more than 10,000 duels took place within a roughly 20-year period. As you probably know if you're familiar with Dumas' The Three Musketeers, which later reinvoked the practice to entertain Victorian readers, duels normally occurred as a result of some form of an offense occurring between one party and another: an insult, perhaps, or, also commonly, physical attacks.

The offended party might challenge their agitator verbally, with a slap — perhaps, famously, with the back of a glove — or even via written note. The pair would then meet and duke it out with swords, sabers, or pistols. According to historian Geri Walton, all aspects of their encounter from the moment of the insult onward were governed by a set of rules called a "code duello," which sought to define how such a brutal practice might be undertaken both fairly and honorably. Dueling etiquette was altered and adapted throughout the centuries, and although the practice thankfully died out, the final duel in France enacted under such guidance occurred as recently as 1967.

Victorian women could only gift handmade items

The Victorians were famously mad for etiquette and social ritual, which says a lot about the values of British society at the time. (We're going to mention quite a few of their crazy rules, don't you worry.) One bit of etiquette gives quite an insight into the role of women back in the 19th century: that, in what was often a busy social life filled with gatherings, salon, and regular afternoon "visiting hours" for both friends and acquaintances, it was considered poor form for a woman to ever gift store-bought objects. Why?

According to Cynthia Bornhorst-Winslow, the practice was all about the signals that homemade gifts gave to wider Victorian society, as well as what they said about the woman gifting them. By creating gifts with religious significance, Victorian women could communicate their own morality or chastity, during a period when such an aspect of one's character be could make or break for your chances of landing a husband — which, at the time, was basically all that families wanted women to do. Marriage was tied to social standing, with dowries being the principal motivators for many families seeking marriages.

Homemade crafts also signaled a woman's domesticity and her "purity" in being desirably cut off from the outside world.

Victorians wouldn't ask direct questions

It might be argued that saying exactly what you mean is celebrated in the 21st century. It shows honesty, and in a world where we are superconnected and constantly communicating across multiple media, it doesn't suit our current lifestyles to beat about the bush too much. But back in the 19th century, decorum dictated that skirting around an issue was the polite thing to do, even to the point that it was considered bad etiquette to ask direct questions in public, per Good Housekeeping.

For example, at a fancy Victorian gathering, no one would ask, "Sir, how are your mother's hemorrhoids?" (Though, to be fair, it's unlikely someone would ask that at a party today.) Rather, they would turn it into something indirect: "I do hope your mother is well." It's a remark that can be answered in a number of ways, giving the receiver ample leeway to avoid discussing his mother's, er, problems. This example illustrates the purpose of the rule, but the etiquette itself went further than preventing blushes and dictated the style of speech that we're aware of today from period dramas and Jane Austen novels.

Performing on command

Ever been hassled to perform a party trick in front of people when you really don't feel like it? Good thing you weren't around 120 years ago.

Folks living in the 19th century obviously didn't have the myriad distractions and entertainment devices that we live with today. They had to make their own entertainment. Often, this would include making things, reading aloud together, socializing in groups at salons and parties, and making music.

But because sources of entertainment were so few and far between back then, it meant that turning down an invitation to perform was really bad form, according to Past Factory. Instead, etiquette dictated that whatever you were requested to do — sing a song, perform a dance, recite a poem that your interlocutor knew you knew by heart — you damn well did it, and without delay. Victorians were probably happy to oblige most of the time, but what about those days when you just really don't feel like it? It couldn't have been easy.

Strange rules for whom you should marry

Also in the late 19th century, the etiquette around marriage, who should marry whom, what the courtship should be like, was rampant. If you feel like you're ever under pressure to get married nowadays, it's nothing compared to what young people — especially women — had to put up with in terms of social pressure back then.

It was all about marrying into a wealthy or respectable enough family. Love didn't come into the equation very much at all, at least in the early stages of the courtship. On top of that, there were some other hilariously shallow codes and practices at play in the marriage madness of the 19th century. As detailed by the Old Farmer's Almanac, Thomas E. Hill's popular etiquette guide Manual of Social and Business Forms contains some jaw-dropping advice for young singles seeking a spouse: "Anyone with bright red hair and a florid complexion should marry someone with jet-black hair. The very corpulent should marry the thin and spare, and the body, wiry, cold-blooded should marry the round-featured, warmhearted, emotional type."

This idea that two people could "balance" each other out in marriage is pretty odd — but then again, they do say that opposites attract.

Only small talk allowed

Though Victorians seemed obsessed with morality, etiquette, social standing, and gossip, they had some strikingly restrictive rules when it came to what you were allowed to talk about. In fact, Victorian gatherings tended to be dominated purely by small talk, according to Playbuzz. The issue seems to have been that to bring up anything that might have been considered even remotely controversial could lead to people openly taking sides on the matter — which could lead to disagreements and, worse still, offense.

It's a far cry from discourse today, in the 21st century, which is increasingly politicized and made up of increasingly polarized opinions and stances, exacerbated by online discussion and the tribalism and heated exchanges that such new media allows for. Come to think of it, perhaps the Victorians did have their own version of an internet flame war — a strongly worded letter to the editor of the local newspaper.

Chaperoning

Though still practiced in some countries, chaperoning is now best known to many of us as a plot device in old American sitcoms from the 1950s and '60s. The idea is that dating couples — or "courting" couples, as they used to say — would also be accompanied on their meet-ups by a third party, a "chaperone" who would basically make sure they weren't getting up to no good before marriage.

According to Prohibition: An Interactive History, this practice, which has its roots in the very family-centric idea of courtship that existed in the 19th century, eventually died out during the Prohibition era, during a greater societal swing against conformity by young people who had been through the scarring experience of World War I. And it really isn't too difficult to work out why chaperoning went out of fashion. As many sitcoms have made clear, chaperoning is a perfect recipe for an awkward night out, with the added bonus of ensuring that the young couple doesn't really get to know each other in any personal or intimate way at all.

Ignoring your babies

The overwhelming maelstrom of advice that new parents can find and stress over on the internet is not a new thing. Guidebooks claiming to be the authority on rearing healthy kids have been around for centuries. And some of the advice that has been put out over the years would look alien to us today — or even downright cruel.

Aside from the homely advice to bathe babies in lard and to calm them with shots of liquor (really), some of the worst offenders in terms of parenting etiquette arise out of some pseudoscientific claims regarding the negative effects of physical interaction with your own baby. Per Slate, as recently as 1916, medical practitioners were warning that to bounce a baby on one's lap would run the risk of giving them nerve damage. Not much earlier, physicians were making the bizarre claim that to play with a baby before the age of four to six months was also bound to make the infant develop physiological abnormalities.

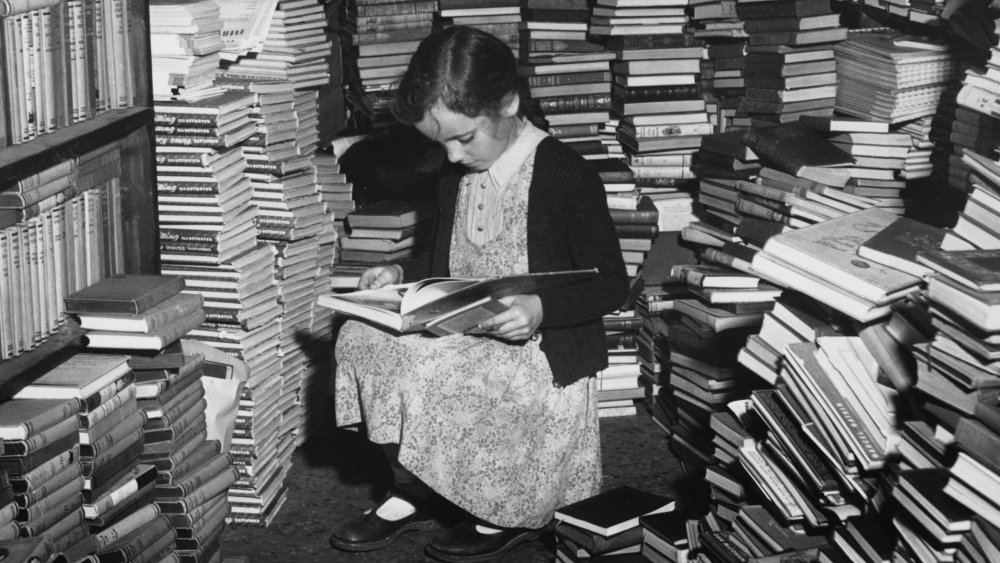

Children should be seen and not heard

This is a phrase that even many millennials can remember from their own childhood, though in recent years, it has often been deployed more as a plea for some quiet than a parenting maxim. The praise originated in England during the 15th century but is especially representative of the societal attitudes toward children and their role within the family in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Most societies now generally accept the childhood need for interaction, self-expression, and creativity. But according to How To Adult, a century ago, the same people who were telling parents to ignore their babies were also telling them that their children's brains were basically like a sheet of blank paper and that, until they were more fully developed as human beings, they were not to be given the benefit of the chance to share their own opinions or to properly interact with the adults around them. The expected childhood behaviors of quietness and meekness were reinforced in schools, where children were taught discipline via corporal punishment.

Smiling on the telephone

Speaking clearly on the phone is something we're generally taught to do nowadays, but back in the early 20th century, as the telephone became an increasingly popular mode of communication, further unexpected etiquette also arose.

Smiling on the phone sounds, on the face of it, like a truly dumb social rule. There have been other rules when new technology arises, such as in the early days of automobile travel when drivers were supposed to toot their horn as they approached pedestrians so they could hear the vehicle coming. These are laughable today but make a kind of crude sense. But who benefits from smiling on the phone?

Per Envisioning the American Dream, in the early days of the telephone, calls were put through to switchboard operators, who asked you for the number and then relayed you to the line you wanted to speak to. The operators were nearly always women, with journals at the time claiming that the dulcet tones of the female "voice with the smile" would calm users who might otherwise become impatient with the service. In response, certain society guides encouraged callers to respond in kind, to show respect for the "Girl on the Switchboard" and also because the smiling telephone user generally receives "the best service."

Etiquette for etiquette's sake

The demand for etiquette guidebooks and training in the accepted behaviors of social life is still surprisingly high. Time Magazine suggests that, for Americans, this stems from a shared sense of "status anxiety" arising from the concept of the United States as a "society of equals," basically that the country doesn't have such a rigid class system as many of its European counterparts.

But the rules, as Time also mentions, that American society deems to be correct are co-opted from such class-based societies, and the truth is that such attempts at mimicking etiquette show little more than the desire to carve society up along the same lines. Because although many of the strange and outmoded codes of behavior of the past had their origins in something akin to practical necessity, many more do not and exist solely for those in the know to tell themselves apart from those who aren't.

The purpose of such behaviors is nothing but exclusivity masquerading as manners, or etiquette for etiquette's sake. It's worth stepping back occasionally to try and examine what this looks like in today's society, as difficult as that may be without the wisdom that hindsight offers.