The Crazy True History Of Death Masks

Throughout history, death masks have been used to commemorate and remember the deceased. Typically, they are made shortly within a few hours after a person passed away and depending on the culture, were either buried along with the person or were kept as a reference for the living.

Dating back to the Ancient Egyptians, death masks can be found all over the world from various historical eras. While the process of making death masks has varied, the end result was always an eerie representation of a lifeless face. For many, death masks became a morbid curiosity as the faces of famous personalities were immortalized. Even one of the most famous waxwork exhibitions today originated from the making of death masks.

The applications of death masks ranged from being used as a reference for artists to justifying pseudo-scientific beliefs. Although not all the death masks throughout history have survived, many are still housed in universities and museums. And while death masks were typically reserved for people, even Dolly the cloned sheep has had her likeness preserved in a mask. Although the practice of creating death masks is no longer as widespread, some continue this macabre tradition to this day. This is the crazy true history of death masks.

So what is a death mask?

Death masks are a sculpted plaster, wood, or wax cast made of a person's face shortly after they die. Before the invention of photography, they were the most accurate depiction of someone who had passed away. According to The Corpse: A History by Christine Quigley, the preservation of one's image was considered a sacred duty across cultures throughout history.

The face was considered to contain "the secret of the personality" and it was out of a desire to save this identity that death masks became common practice. Combining the accuracy that one would get from a photograph with the dimensionality of a sculpture, the death masks did not merely evoke the dead, but they were the dead brought to life.

Traditionally, death masks are made by oiling the head and pouring plaster over it to make a mold. This way, the original mold may be repeatedly used. Often, artists used death masks as references to sculpt and paint portraits for royal halls and tombs. In the tombs of ancient cathedrals in Europe, almost all the faces of nobles that one comes across were typically copied from death masks. According to The Royal Society, masks may also be made from a person while they are still alive. Samuel Pepys, a member of the British Parliament, undertook the creation of his own "life mask" in 1669.

Don't forget this face

In Ancient Egypt, death masks were considered part of the funeral rite. Ancient Egyptians believed that the body should be preserved in death through mummification because, without a body, the soul would have no resting place. According to History of Masks, it was equally essential that the soul was able to recognize the body after death, and so death masks were used to portray the person's likeness and help guide the soul back to the body.

Early Ancient Egyptian death masks were made out of two pieces of wood that were connected with pegs. This process evolved to incorporate cartonnage, a material made out of linen or papyrus that had been soaked in plaster and molded over wood. Death masks often portrayed people with slightly larger eyes and a hint of a smile.

Royals made their death masks out of metal, often gold or gold atop bronze. The most famous death mask of this kind is the death mask of Tutankhamun (above). According to SmartHistory, Tutankhamun's death mask is considered a masterpiece of Ancient Egyptian art. Weighing over 20 pounds, it's made out of two gold sheets hammered together. Tutankhamun's death mask portrays him wearing the nemes headdress worn by pharaohs, along with a false beard, connecting him with the gods. The back of the mask is also covered with a spell from the Book of the Dead, meant to protect the limbs of Tutankhamun during his journey into the underworld.

The waxy faces of death masks

In Ancient Rome, death masks were used as effigies and instead of wood or plaster, they were typically made out of wax or beeswax. According to Penn Museum, these masks were unlike traditional death masks and more akin to life masks since they were created while the person was alive — generally between the ages of 35 and 40. After their death, the death mask was worn by family members or mourners during the funeral procession.

Death masks were also established by the second century B.C. and may have been used as late as the sixth century A.D. According to Imperium Romanum, after the funeral, the death masks were typically kept by the family in their atrium in order to emphasize the significance of their family and to preserve the memory of their ancestors. Often, these masks would also be displayed next to labels that described the highest political office that had been held by the deceased.

Unfortunately, because these death masks were made of wax, there are no surviving versions and our knowledge of them is based on literary accounts. Death masks made out of wax were also limited to aristocratic families while non-elite Romans made plaster death masks that were undoubtedly inspired by the wax masks of the elite. Ancient Roman death masks were also typically only made for men.

A resting gold face

In the 1800s, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann set out to discover the grave of Agamemnon and other remnants of the Trojan War. According to Ancient Origins, in 1876 Schliemann was excavating Mycenae where he discovered a series of shaft graves. In these graves, he found many remains, five of whom were wearing gold foil face masks.

According to the Archaeological Institute of America, Schliemann promptly sent a message of King George of Greece stating that he had discovered the graves of Eurymedon, Cassandra, and Agamemnon. Upon seeing the masks, Schliemann telegrammed a newspaper saying, "I have gazed on the face of Agamemnon," although he never identified which mask he meant. As a result, one of these masks became famous as the mask of Agamemnon, despite the fact that Schliemann never truly identified the mask as having belonged to Agamemnon himself.

Though it was later proven that the graves excavated by Schliemann predated Agamemnon and the Trojan War by 300 years, the mask remains associated with Agamemnon (see above). However, with its distinctive features, the mask most likely did belong to a ruler of Mycenae and is now considered an example of the artistry typically found in royal Mycenaean graves.

Death masks were a tool for artists

During the Middle Ages, death masks were often used as memorials to the deceased and, like Ancient Roman masks, weren't buried with their original. Across the globe, Native American, Indigenous African, and Oceanic tribes considered death masks an essential part of social and religious life. The death mask was believed to open a path for communication during funerary rites.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, in medieval England and France, actual death masks were incorporated into the royal funeral effigies rather than merely providing a reference for sculptures. However, only English versions were preserved, such as the death mask of Edward III and Henry VII. Medieval French death masks were most likely destroyed during the French Revolution.

Overall, according to The People's Almanac by David Wallechinsky, the main purpose of European medieval death masks was to act as a model for artists in their creation of statues and busts of deceased people. European medieval death masks were also primarily used to preserve the representation of nobility.

During the Renaissance, this practice shifted towards preserving the representations of celebrities, such as the Medicis. In Renaissance Italy, death masks became a popular item to have and began to be displayed more in private homes than in churches. People would furnish them in frames or wreaths and even have them hanging in windows or doorways.

Madame Tussaud is born

During the 1700s, waxworks were already a popular public attraction but during the French Revolution, they were taken to another level. During the revolution, Marie Grosholtz, who would later become known as Madame Tussaud, was compelled by revolutionaries and the government to make waxwork reproductions.

Working with the famous anatomist and waxmaker Philippe Curtius, Grosholtz made death masks of those decapitated during the French Revolution. According to Madame Tussaud: And the History of Waxworks by Pamela Pilbeam, the decapitated heads were initially displayed on pikes to confirm the victory of the masses. After being briefly displayed, the heads were quickly rushed to Grosholtz in order for her to make impressions of the bloody heads. Grosholtz also sought out heads on her own. When Jean-Paul Marat was murdered in his bathtub, Grosholtz got to the dead body so quickly that the killer Charlotte Corday was still being processed by the police when Grosholtz commenced work on Marat's death mask.

According to National Geographic, after the revolution ended, in 1802, Grosholtz took her collection on a tour through Britain, eventually settling in London in 1835. Her exhibition drew crowds with the death masks of Marie Antoinette, King Louis XVI, and Maximilien Robespierre, and soon expanded to include English royalty. Her exhibit was called the "Chamber of Horrors" by London's Punch magazine for its incorporation of recreated murder scenes. The popularity of these waxworks continued to grow and today, Madame Tussauds Attractions can be found across four continents.

Tsars and revolutionaries alike had death masks

Death masks were made during the Russian Empire but experienced a boom during the Soviet Union. One of the earliest Russian death masks is that of Peter the Great, the first Emperor of Russia, who died in 1725. Upon his death, the Italian sculptor Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli, who had worked as a sculptor for the Emperor, went to the palace in order to make plaster casts of Peter the Great's feet, hands, and face. Cast in bronze, the death mask is now housed at the Russian Museum.

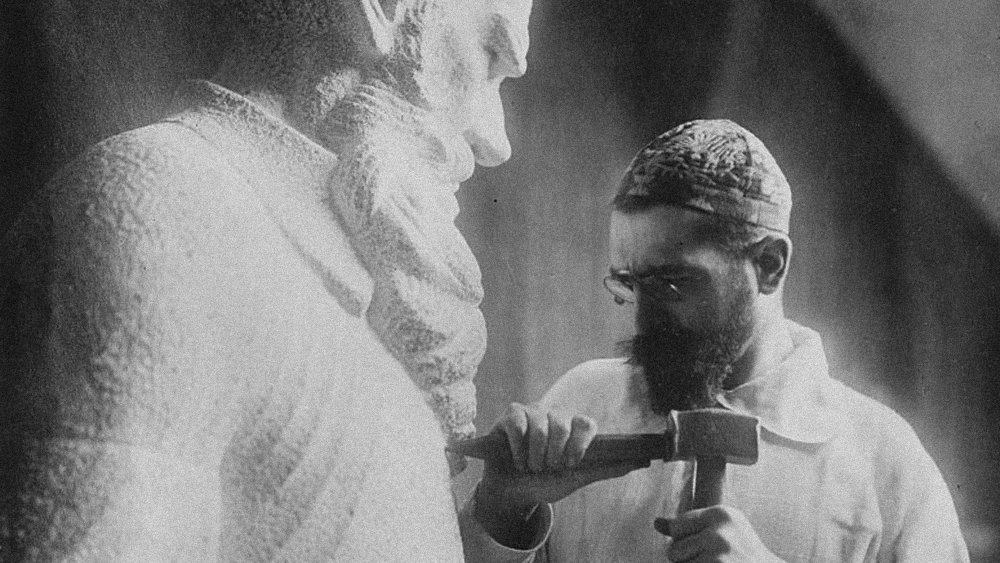

During the Soviet Union, the sculptor Sergey Dmytrevich Merkurov became known as the master of death masks (above). According to Gurdjieff Club, Merkurov made his first death mask in 1907 of Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian. Throughout his life, he went on to make the death masks of Hovhannes Tumanyan, Leo Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky, and Vladimir Lenin.

According to Russia Beyond, Merkurov made upwards of 300 death masks before his death in 1952. Merkurov was often called upon to make death masks of party leaders such as Mikhail Kalinin and Yakov Sverdlov. His death mask of Lenin is his most recognized death mask, and he went on to use Lenin's death mask as the basis for many sculptures and monuments with Lenin's image, just as medieval artists had once done. The culture of death masks began to fade after Stalin's death, and the last known death mask of a Soviet leader is thought to be that of Boris Yeltsin.

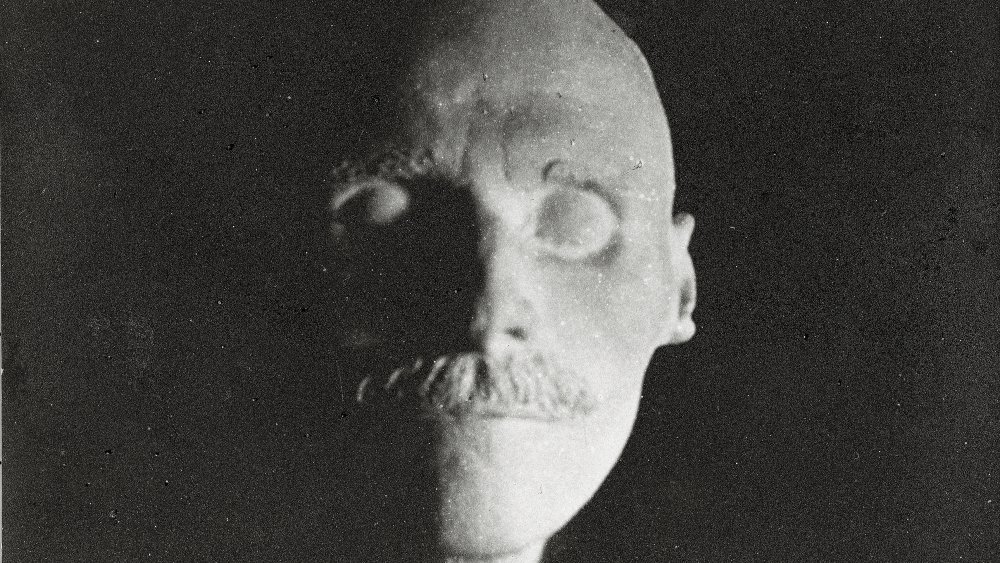

Pseudoscience gets a taste for death masks

During the 18th and 19th century, phrenology was the pseudo-scientific belief that a person's mental faculties and personality could be derived from the shape of their skull. According to University College London, in the mid-1800s the German phrenologist Robert Noel began collecting death masks in order to illustrate phrenological principles. This wasn't an uncommon practice, for The Edinburgh Phrenological Society, founded by George Combe in 1820, also amassed a collection of death masks for the purpose of phrenological study.

According to Buzzfeed, Noel categorized the death masks into two categories: "Intellectual" or "Criminals and Suicides." One such example is the death mask of Johanne Rehn, who was categorized as "Criminals and Suicides." Rehn had fallen in love with a married soldier and fearing that he wouldn't marry her due to her status as an unwed mother, she murdered her child. She was executed as a result, and in the description of her death mask Noel wrote that she was deficient in "benevolence" and "love of children."

The "Intellectual" category included people such as Thomas Horlock Bastard, Esq, who built a reading room for laborers and shopkeepers, and Karl August Böttiger, the director of the Museum of Antiques in Dresden. Between 1837 and 1845, Noel collected upwards of 35 life and death masks.

Mask of criminality

During this period of phrenological study, a great many death masks were made of criminals who had been executed. According to LLIFS, the death masks of criminals were used for phrenological study in addition to being showcased in museums. Prison authorities also used them for lectures and showcased them in an effort to dissuade people from committing crimes, lest they wanted their death masks to be forever displayed.

According to the BBC, in Worcestershire, prisoners who were hanged had their bodies transported through an underground tunnel and were taken to the Worcester Royal Infirmary where death masks were made and their bodies dissected. The Metropolitan Police's Crime Museum also amassed a collection of death masks of various criminals. Many of these death masks were from criminals who had been executed at London's Newgate Prison and before its closing in 1902, the death masks were on display at the home of the Governor of Newgate Prison.

The practice of making death masks of criminals was common across the Atlantic as well. According to The Corpse: A History by Christine Quigley, the crime lab of the Chicago Police Department displays the death masks of "Baby Face" Nelson and John Dillinger (above), both of whom were killed by the FBI in 1934. The death masks of Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco were also displayed in New York City in 1927 after their controversial conviction and execution.

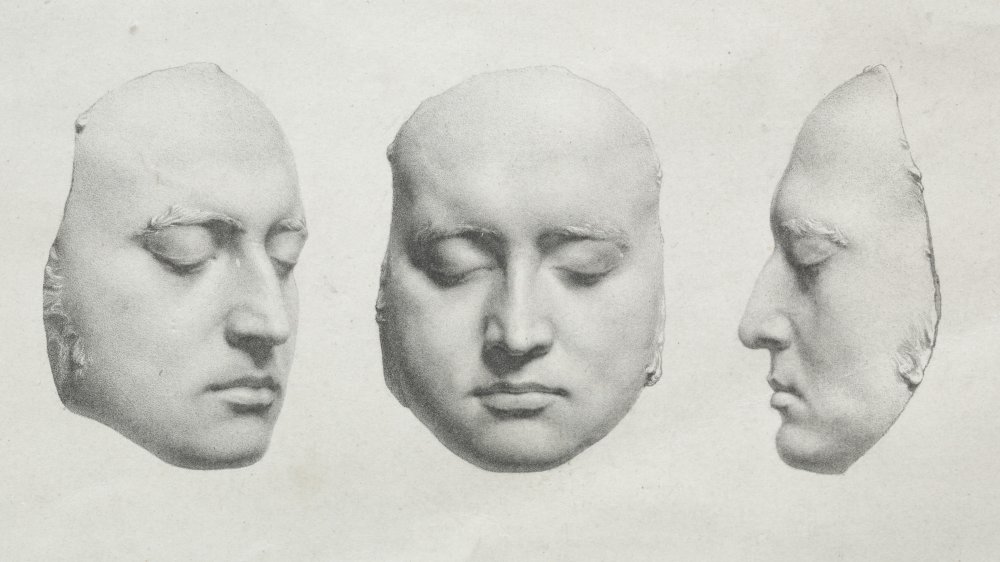

The drowned Mona Lisa

Sometime between 1870 and 1880, a young woman was found drowned in the Seine River in Paris. Taken to the morgue, her death was determined to be a suicide due to a lack of visible struggle. According to Mental Floss, the pathologist working at the morgue reportedly found her face to be so beautiful that he made a death mask.

She became known as "L'Inconnue de la Seine," the unknown woman of the Seine, and her death mask captivated people with its enigmatic hint of a smile. According to Science Alert, copies were soon being made and sold in souvenir shops across Europe. The philosopher Albert Camus even described her as the "drowned Mona Lisa."

The death mask of L'Inconnue de la Seine became an inspiration for writers and artists. Richard le Gallienne was one of the first to feature her in a story in his novella The Worshipper of the Image. According to Hyperallergic, she was also mentioned by Rainer Maria Rilke in his 1910 novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge and was also immortalized by Vladimir Nabokov in his 1934 poem titled "L'Inconnue de la Seine."

Her death mask's fame didn't stop there. In the 1960s, the Austrian doctor Asmund Laerdal was inspired by the beauty of the mask and decided to use it as the model for the first CPR dummy, known as Resusci Anne, or CPR Annie. As the first and most successful CPR dummy, she's said to have the "most kissed face of all time."

Famous death masks

The popularity of death masks throughout history is demonstrated by the many death masks made of famous historical figures, many of which are still on display today. According to The Corpse: A History by Christine Quigley, castings of Napoleon Bonaparte's death mask (pictured above), based on the original mold taken by Francis Burton in 1821, can be seen today in European museums.

The Royal Society currently houses one of the death masks of Isaac Newton, as there were several made after his death, most likely by the Flemish artist Michael Rysbrack. The German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had both a life mask and a death mask made, both of which may be seen at The Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks.

After his death in 1658, Oliver Cromwell's death mask was taken by official engraver Thomas Simon. However, there are several plaster casts of Cromwell's death masks and since they aren't identical, it's possible that multiple death masks were made. Other famous historical death masks include those of Ludvig van Beethoven, Dante Alighieri, and Isaac Newton.

Death masks never die

The morbid appeal of death masks has yet to fade. Nick Reynolds, a member of the band Alabama 3, is a contemporary creator of death masks. According to The Guardian, Reynolds has made death masks of Pat Castange, the composer of Trinidad and Tobago's national anthem, actor Peter O'Toole, and a Swiss United Nations official. Keeping with the tradition of death masks, Reynolds has also made a death mask of John Joe Amador, an American man who was executed in Texas in 2007.

According to Vice, Reynolds is fascinated by the tangibility of death masks, stating that they have a magic about them that cannot be found in a photograph. But he came into this line of work accidentally. Reynolds was looking to explore the paradox of criminals who are vilified by the media while simultaneously being given a cult of celebrity.

In the process of making life masks of some of England's infamous living criminals, one of the men on his list died. Undeterred, Reynolds thought that a death mask wasn't so different from a life mask, especially since he wouldn't have to worry about breathing movements, so he made his first death mask of George Taters Chatham. After having family friends reach out for death masks and realizing that there weren't many others creating them, Reynolds decided to make it his specialty.