The Heartbreaking Tale Of Saartjie Baartman, The 'Hottentot Venus'

The world is made up of all different kinds of people, and they're all, well, very different. Many have always had a fascination with those who aren't like themselves, and sometimes, that's ended very poorly indeed.

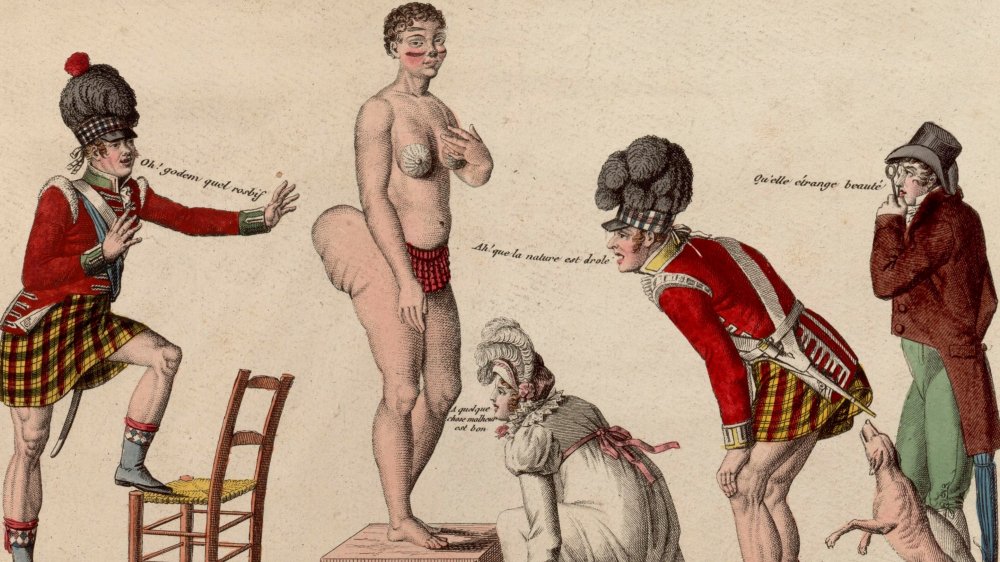

For centuries, that's led to the uncomfortable, degrading practice of exhibiting "others" for the amusement of those who see themselves as somehow superior. Throughout the 19th century, those exhibitions even took the form of organized "human zoos," and if that isn't enough to make someone lose faith in the human race, then nothing is.

Even before that, people deemed strange or foreign were often exhibited in other ways, and there's no story that's sadder than that of Saartjie Baartman. When she was plucked from her homeland in Africa and taken to Europe to go on display, she was renamed the "Hottentot Venus," (and we'll look at why that's so particularly horrible). Much of Baartman's short life was spent being ogled and touched by strangers who grossly exploited her.

Saartjie Baartman has long been a mystery

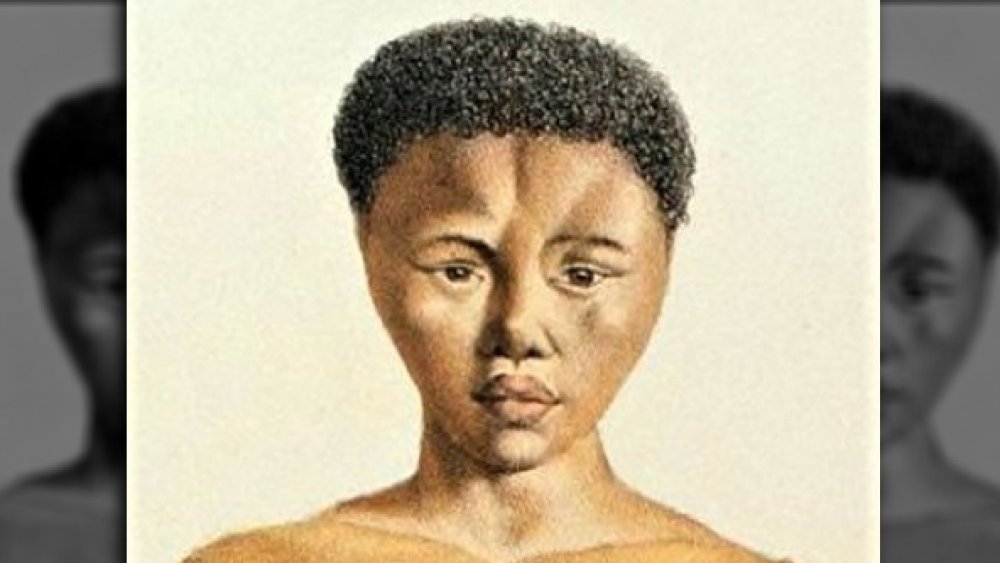

Saartjie Baartman has long been something of an enigma: known by her stage name, the Hottentot Venus, we know that she was put on display to gratify the curiosity of European viewers. But, who was she?

That's the question Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully asked when they started getting curious about the woman behind the costume. They did some digging (via Johns Hopkins), and — after some detective work that would make Sherlock Holmes proud — they found some new insight that proved long-accepted history wasn't entirely correct.

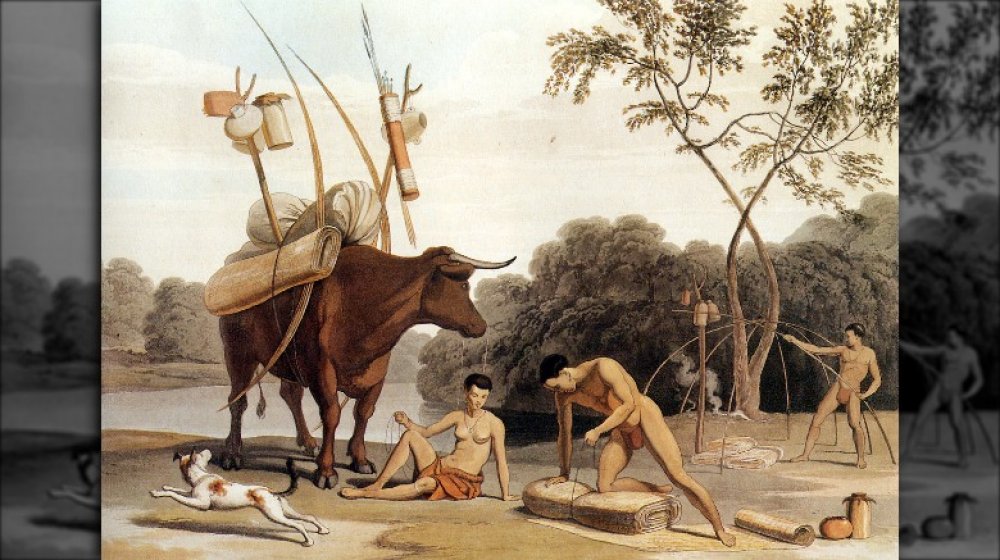

Crais and Scully discovered that, contrary to popular belief, Baartman was born sometime in the 1770s (not in 1789, as often said), in an area called the Green Valley, or Camdeboo, around 400 miles from Cape Town. It was a turbulent time: her people, the cattle-herding Gonaqua, were being actively hunted and enslaved. After the deaths of her parents, she moved to Cape Town — which was, at the time, a bustling, metropolitan port city that had a constant influx of European ships and men. There, she became what Crais and Scully described as "a slave in all but name," serving a series of enslavers and giving birth to three children (who all died in infancy).

While the Hottentot Venus is often painted as a simple or innocent caricature of a woman, Crais and Scully discovered something different: "Our position is that Sara Baartman, while in Cape Town, was basically a cosmopolitan woman who had a great deal of information on European men, including their interest in black women's bodies."

Saartjie Baartman heads to Europe

Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully say that one of the masters Baartman worked for was the Cesar (or Cezar) family, Johns Hopkins Magazine reports. South African History Online suggests that it was Pieter Willem Cesar who first bought her, and she was forced to work for his brother, Hendrik in Cape Town. Here, her name was changed from Sara to the diminutive Saartjie.

It was while working for the Cesars that Baartman caught the eye of an English ship's surgeon named Dr. Dunlop, who seized an opportunity to secure some extra cash for his upcoming retirement. Dunlop was the one who concocted the plan to take her back to London and exhibit her around town.

Here's where the facts get stickier: No one's entirely sure just how much of a say Baartman had in any of this. The long-standing belief was that she was simply told what she was going to do then exploited. However, Crais and Scully suggest something different. The plans to take her to England were developed over the course of months. Reportedly, not long before she boarded the ship for Europe, Baartman had told Cesars' wife: "Who will give me anything here?"

Was she forced to exhibit herself, or did she see it as one of the only opportunities she had of possibly escaping a life of servitude and slavery? She may have had little agency as an enslaved woman, but it's worth noting that she owned the copyright to several of her early images.

Rebranding Baartman as the "Hottentot Venus"

According to South African History Online, Saartjie Baartman, Cesar, and Dunlop entered into an agreement: she would go to Europe with them and perform, in exchange for a "portion of earnings" and — in five years' time — her freedom to return home.

Two things make this so-called contract dubious: Baartman came from a culture that didn't make written agreements of that sort, and at the time, the Cesars were experiencing some serious financial difficulties. It's unlikely that they would have voluntarily released her.

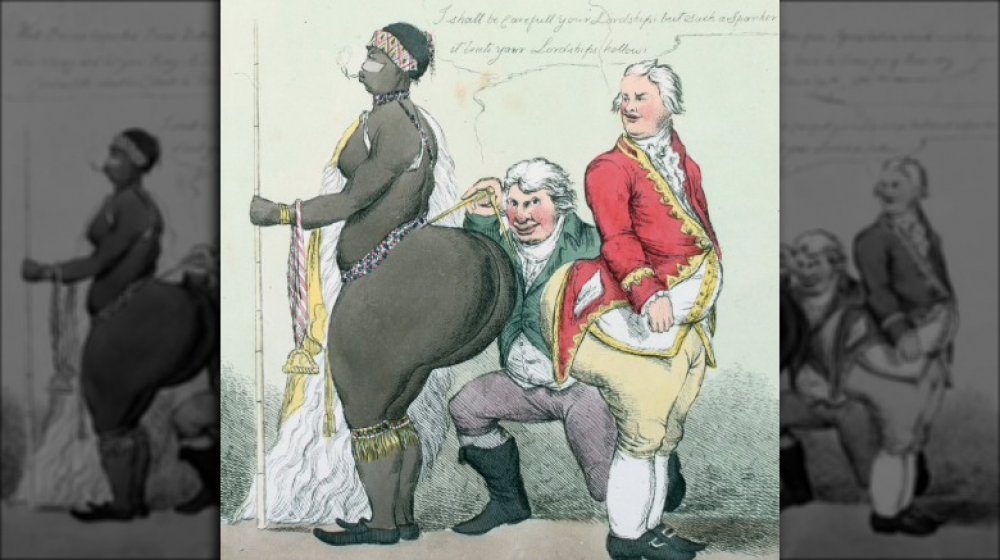

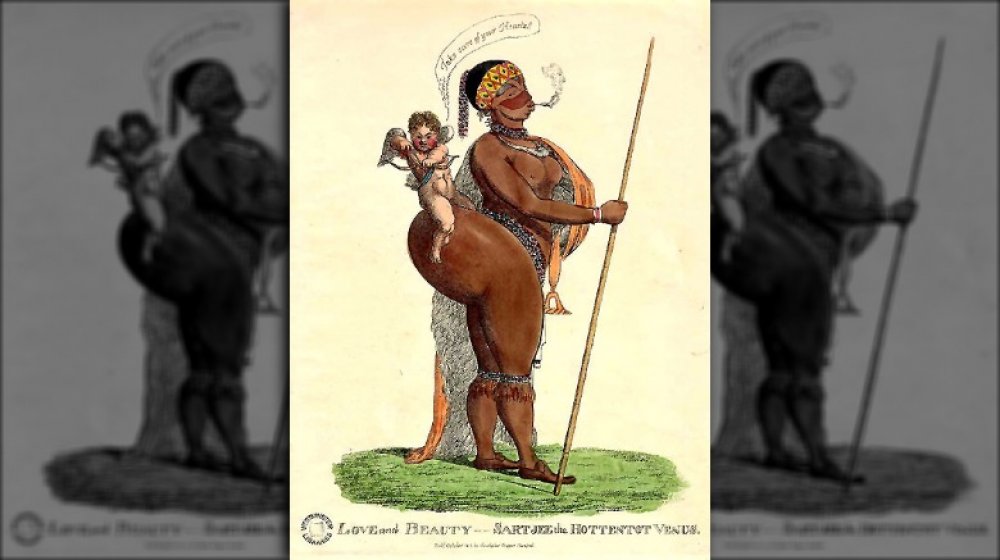

Regardless, Baartman was re-branded as the Hottentot Venus for her stage act, and that's problematic for a few reasons. According to Crais and Scully (via Johns Hopkins), "Hottentot" is an extremely derogatory term that means "to stammer," and refers to the way in which Dutch colonizers heard and described the native Khoisan language. (For example, an 1820 cartoon depicted the imagined fate of explorers to the Cape: "to be half-roasted by the sun and devoured by the natives," according to the caption.)

And as for "Venus," that was a reference to the goddess of love, but it was a term that Transforming Museums says came with a bit of "sarcasm, scorn, [and] a sneer on the part of nineteenth-century Europeans."

And those same 19th-century Europeans loved to look at her.

From South Africa to the London stage

So, what was it about Saartjie Baartman that had so captivated European audiences, and convinced Cesar and Dunlop that her exploitation would be profitable?

According to Salon, Baartman was described as "a pretty maidservant with notable buttocks and a spotty giraffe skin." As far as the most proper areas of London were concerned, that made her a perfect addition to the stages of Piccadilly. That's the area of the city, says The New York Times, where all of the "so-called human freaks" were put on display, and Baartman joined acts that included the 19-inch tall "Sicilian Fairy" and the "Living Skeleton." She was exotic, unfamiliar, and she was unlike anyone else that was walking the streets of London.

It was Baartman's sexuality that was on full display, and those who were exhibiting her made the most of it by dressing her in a skin-tight, flesh-colored outfit. The Guardian notes that her most widely advertised features — her backside and her genitalia, which was advertised as "resembling the skin that hangs from a turkey's throat" — were typical of her Khoisan heritage. In Europe, though, she became what the University of London professor Rachel Holmes describes as a "symbol of the alienation and degradations of colonization, lost children, exile, the expropriation of female labor and the sexual and economic exploitation of black women."

Saartjie Baartman's portrayal as the "savage" and the "deviant"

Regardless of whether or not Saartjie Baartman was compliant in the move to Europe, The New York Times says that it took its toll: as the years wore on, she increasingly relied on alcohol to help make her dehumanizing reality more palatable. It was a reliance that turned into an addiction.

And honestly, it's no wonder. Her exhibition was nothing short of horrible, something anti-slavery campaigner Zachary Macauley described (via the National Archives) as being done "in the same manner that any animal of the brute creation would be exhibited."

Macauley wasn't kidding: according to research done by the University of Malaga, Baartman often was given instructions by her "keeper," who told her what to do to keep the audience entertained.

The backdrop of the stage behind her was often a generic sort of scene from pastoral Africa, and she was illuminated by torches and firelight, told to dance on command, and ordered to play various instruments when her "keeper" told her to. The Guardian recounts that after some time on exhibition at Piccadilly, the venue was moved to Bartholomew Fair and then to Haymarket. All the while, audiences hooted and hollered at her on stage. And sometimes, they could get ever closer: Time says that for a fee, audiences could get up close and personal with her during private showings, where wealthy patrons could arrange to touch her.

There was — briefly — an attempt to free Saartjie Baartman

There was an anti-slavery movement in Europe at the time Saartjie Baartman was being exhibited, and according to the National Archives, there was at least one attempt to free her. In 1810, the English legal system was presented with a writ of habeas corpus, and the claim that she was essentially being held prisoner, and exhibited against her will. What resulted was an appearance in court and a session that Time says was her one and only interview, given in October of that year, during which she not only said that she was happy doing what she was doing, but that she was doing it freely and being compensated for her work.

It's also worth noting that the original interview is long lost, and in its raw form, only existed as a paraphrased translation from her testimony, which was given in Dutch. That's left a number of unanswered questions about the authenticity and truthfulness of the interview.

The National Archives says that the case that had been brought to the court collapsed when she gave her statement, which included the interpreter's report that she "was perfectly happy with her present situation." While it was argued that Baartman didn't understand the agreement that was made — or that attempts for her emancipation were being made — the case was dismissed, with the caveat that if someone were to complain that her exhibition was indecent, that might be another story.

Saartjie Baartman was sent to France

Saartjie Baartman's original costume — a skin-tight and flesh-colored outfit — left little to the imagination, and audiences began to murmur that it was just indecent. In order to try to avoid going to court again, Time says that Dunlop switched things up, and put Baartman in a less revealing kind of tribal-like costume.

But it turned out that audiences just wanted to seem like they were being all prim and proper, while what they really wanted was to objectify and exoticize Baartman in as little clothing as possible. Attendance dropped, and that's when Dunlop decided to cut his losses. He sold Baartman to a French animal trainer named Sieur Reaux (via the University of Malaga).

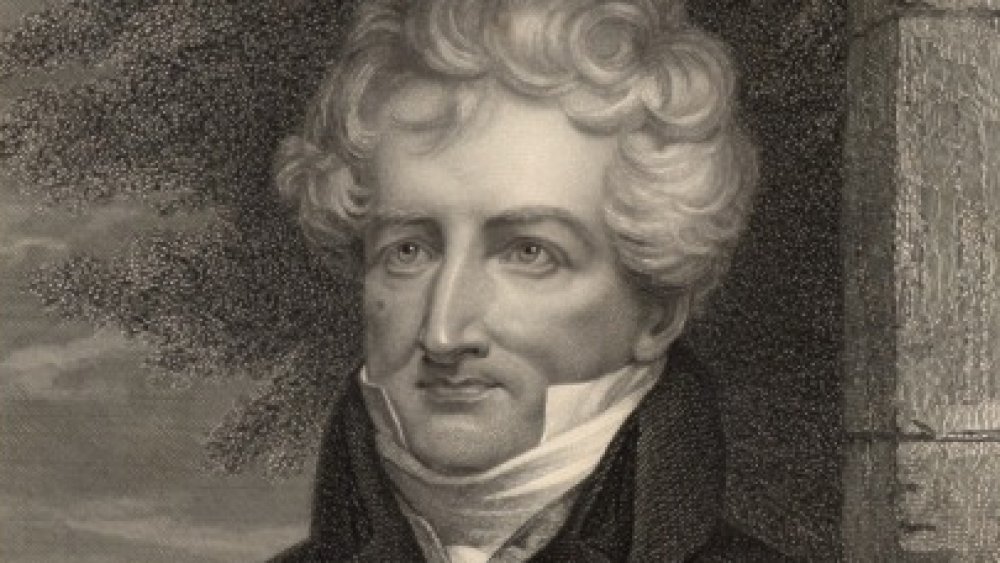

Baartman was taken to Paris, says the Guardian, where she continued to be exhibited both in public and private shows, often clad in nothing but a few feathers ... while living in squalor, staying in an apartment that shared a building with a brothel (via Johns Hopkins). It was at one of these shows that she caught the eye of Napoleon's surgeon general, Georges Cuvier (pictured).

Cuvier became obsessed with Baartman, and — as the Professional Chair of Comparative Anatomy at the Natural History Museum — used her close proximity as an opportunity to measure and document her. Cuvier's research went to furthering the cause of racial science. He declared his interest in her "scientific," and not only examined her himself but invited other doctors and anthropologists to get a good long look, too.

Baartman was disrespected even in death

Saartjie Baartman died in Paris during the winter of 1815, and the circumstances were unclear. Her cause of death has been suggested to be everything from pneumonia made worse by the cold, hard winter and the poverty she was living in, to complications from either syphilis or alcoholism (via the BBC). Regardless, her story's about to get even more unsettling ... if that's possible.

After Baartman's death, Georges Cuvier was given her body. Cuvier started by taking a full cast of her body parts. Then, he preserved and pickled her brain and genitals, completely destroying what little modesty she had held onto in life. Despite the fact that her outfits left little to the imagination, Baartman had never appeared fully naked in front of either audiences or scientists. Baartman, who had very little agency, had at least insisted that she be allowed to hold onto that dignity. Cuvier then boiled the flesh from her bones, reassembled her skeleton, and displayed that at Paris's Museum of Man (pictured).

Her preserved organs — including her genitals — were placed in jars and also put on display ... where they stayed until 1974. According to South African History Online, they were only removed from public viewing after the paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould mentioned them in his book The Mismeasure of Man, which was a scathing condemnation of the idea of racial science. While they were removed from public view, they still remained in France.

Racism, colonialism, and sexism

Georges Cuvier also recorded his findings (via Johns Hopkins) — you know, as a scientist — falsely claiming that Saartjie Baartman was proof that "the Hottentots" were creatures closer in nature to apes and orangutans than to European humans. Her legacy is hugely problematic, and a reminder of a time when people who were "different" were put on display in an attempt to validate the racist European beliefs about African people — that they were "primitive" and "hypersexual."

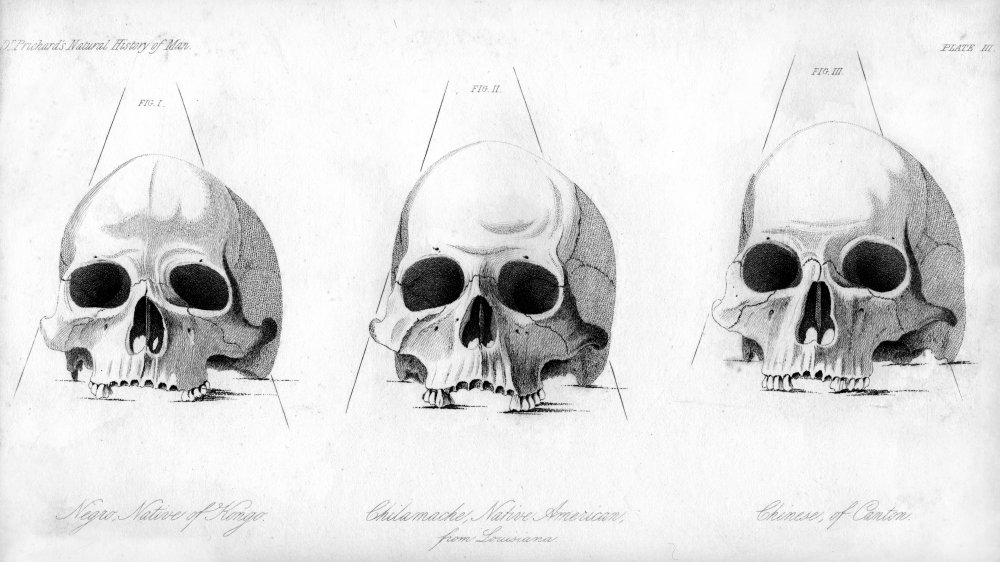

According to the Smithsonian, it was the same time Baartman was being exhibited — the 19th century — that scientists were debating the origins of modern humans... and they believed at the very tippy-tippy-top of the evolutionary scale were white Europeans. To these white scientists, they were the "most evolved and intelligent," and it was widely preached by those who fit nicely into the mold. By dressing people like Saartjie Baartman in skin-tight clothes and exhibiting her "otherness," they strove to prove it. (The photo is an 1848 sketch of a comparison of skulls, a common racist practice in science. Left to right, they were labeled: "Negro, Native of Kongo," "Chilamache, Native American," and "Chinese, of Canton.")

The sort of racial science that resulted in her examination by scientists and doctors of Paris and the gross desecration of her body after death is by no means something old: researchers like Angela Saini, author of Superior: The Return of Race Science, trace it right through the development of eugenics to the Holocaust and World War II, right into the racist IQ tests of the 21st-century.

The movement to bring Saartjie Baartman home

In 1994, Saartjie Baartman got renewed attention thanks to Nelson Mandela. That, according to the New York Times, is when he started leading South Africa in a campaign to get her remains returned to the country of her birth, where she could be given a proper burial near the Gamtoos River (pictured). Even though her remains were "no longer deemed to serve any scientific purpose," repatriation took a long, long time. It wasn't until 2002 that Baartman was taken home.

But the ending of this story is far from peaceful. According to Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully (via Johns Hopkins), her gravesite was vandalized just months after her internment. That wasn't the only time it would happen, either. The BBC reported that in 2015, her grave was still being defaced, despite the fact that Baartman had become an internationally-recognized symbol of the struggles of women suffering from discrimination and sexual abuse.

There was another problem, too. A tall metal fence was erected to protect Saartjie Baartman's grave, which essentially put her, once again, behind bars. Additionally, Crais explains the tragic truth of her resting place: "She's buried at the top of a hill overlooking a river and citrus orchard owned by the descendants of a family that took part in the genocide of her people. She is behind bars in her grave, and no one goes to visit."