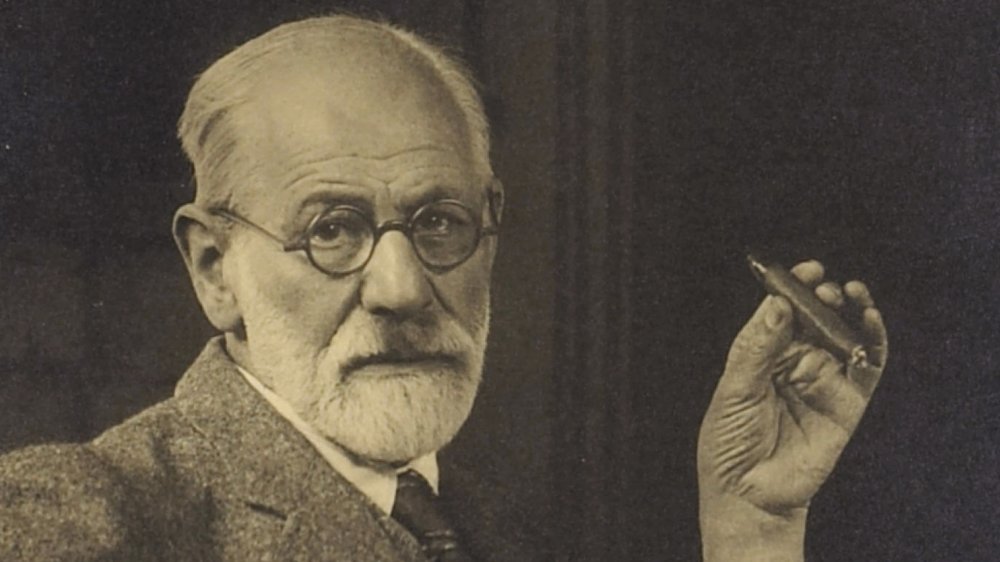

The Truth About Sigmund Freud's Biggest Addiction

According to Quote Investigator, the one line everyone thinks Sigmund Freud said wasn't actually said by Freud: "Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar." Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, the man who taught us to examine intricately the symbolism in our interior (and sometimes exterior) lives, and taught some of us (let's be honest) how to overthink absolutely everything (including dreams), might not have said it. But he should have.

The man loved his tobacco. Just as W.C. Fields advised "Never trust a man who doesn't drink," so Freud was about cigars. As Cigar Afficionado reports, the good doctor was "thunderstruck" when his 17-year-old nephew refused the offer of a cigar: "My boy, smoking is one of the greatest and cheapest enjoyments in life, and if you decide in advance not to smoke, I can only feel sorry for you." As for cheap thrills, it was something Freud took enormous pleasure in: he smoked up to 30 cigars a day, "ceaselessly," even while he conducted therapy sessions for patients.

He was born in 1856, as Biography tells us. The family moved to Vienna when he was 4, and it was there he studied and practiced. He was trained as a neurologist, though he apparently thought of himself more as a research scientist than a simple physician.

Freud explored cocaine as a therapy tool

Part of that research involved helping people understand themselves, the underlying causes of their behaviors, especially behaviors that seemed to be out of control. Part of that was his "talking cure" — patients free-associating while he took notes — but better living through chemistry wasn't off the table, either.

Psych Central relates that in the course of his studies and research, Freud became interested in what he saw as the beneficial aspects of cocaine use. He wasn't the only one. As Dr. Howard Markel, professor of medical history at the University of Michigan, wrote for CNN, in the 1880s, "pharmaceutical houses touted it as a cure for everything from morphine addiction and depression to dyspepsia and fatigue." And it was still legal. Freud began to research cocaine's effects, using himself as a subject — not best practice today, but not unusual then. As History tells it, in 1884 Freud published a research paper, "On Cocaine," "a song of praise to this magical substance," and would give the substance to friends and colleagues as a gift — speaking for himself, he found it aided his digestion and improved his spirits. (He would consume it by dissolving it in a glass of water and drinking.)

Freud tried to treat a friend's morphine addiction with cocaine

A colleague, Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow, had developed a crippling addiction to morphine to cope with the aftereffects and pain of his thumb being surgically amputated. Freud gave his friend cocaine in hopes that it would wean him off morphine. It did, but — perhaps to no one's surprise today — von Fleischl-Marxow instead developed a crippling addiction to cocaine. As CNN reports, "Freud, in essence, transformed his highly functioning, albeit opiate-dependent, friend into an addled cocaine and morphine addict who was dead seven years later at age 45."

Freud later said he stopped using cocaine himself in 1896, after his father's funeral. But as Psych Central quotes Dr. Markel, "the absence of evidence does not always signify evidence of absence." Dr. Freud certainly couldn't get over his dependence on nicotine. He died, age 83, after more than 30 operations for oral cancer. His death was a suicide; he asked his physician for an overdose of morphine. He smoked cigars to the very end of his life.