The Troubled History Of Ponce De Leon

If you think you know anything about the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León, it's probably that he once led a search for the Fountain of Youth. (You'd be incorrect, but don't blame yourself — it's a very popular myth.) If you're more of a history nerd, you might know Ponce de León as the man who explored Puerto Rico and Florida on behalf of the Spanish empire.

This latter belief about Ponce de León is correct, but it's far from the full truth about the 16th-century Spaniard. The real Ponce de León was more than a simple explorer; he was also a governor, colonizer, and military "hero." Over his decades-long career, Ponce de León exploited and subdued the Native peoples of the Caribbean, acquiring a great deal of wealth for himself and for the empire. In a karmic twist, the conquistador would eventually meet his end after being struck by a Native American's arrow.

Here's the story of Juan Ponce de León's troubled, violent life.

Juan Ponce de León helped Spain expel the Moors

Not much is known about the early life of Juan Ponce de León; even his birth year is a subject of dispute, with most historians estimating it was either 1460 or 1474. We do know, however, that Ponce de León was born into a noble family in Santervás de Campos, Spain. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, he spent some time as a page in the royal court of Aragon. Then, as a young man, Ponce de León enlisted in the Spanish army during the final years of the Reconquista — Spain's push to "reconquer" the Iberian peninsula by expelling the Moors living in the south. Ponce de León fought in the battle against the Emirate of Granada, the final Muslim stronghold in Spain. In 1492, Spain was victorious. The Moors were expelled from the country for good.

While Juan Ponce de León no doubt celebrated this nationalist victory, he was also aware that his country no longer needed his military services. So, per History, he likely joined Christopher Columbus' second expedition to the New World in 1493. This voyage would be the start of Ponce de León's long (and brutal) career as an explorer.

Juan Ponce de León crushed a Native American rebellion in the Dominican Republic

Sometime after his 1493 trip to the New World, Juan Ponce de León settled in Hispaniola — the Spanish colony in the Caribbean which now comprises Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The Encyclopedia Britannica reports that, by 1502, Ponce de León was serving as a captain under Nicolás de Ovando, governor of Hispaniola.

By then, Spain had been increasing its colonial presence in the Caribbean for almost a decade, and Native tribes were becoming increasingly agitated by the subjugation they faced. So, according to historian David Marley, a revolt broke out in 1503 among a group of native Taínos led by Chief Cutubano (or Cotubanamá). The Taínos overran a Spanish garrison in Higüey, to the far east of Hispaniola, killing eight of the nine soldiers stationed there. In response, Governor Ovando personally chose Juan Ponce de León to lead a force of 300 to 400 Spanish soldiers to subdue the Taíno rebellion. What resulted was an outright massacre of the Taíno people in Higüey. The violence of Ponce de León's military force was so extreme that Bishop Bartolomé de las Casas, who witnessed the massacre, attempted to notify Spanish authorities.

But it was too late. Within a few months, Ponce de León was able to track down and kill Cutubano, who had been one of the final Taíno chiefs on the island. Higüey, and essentially the entirety of Hispaniola, was now under Spanish control.

Ponce de León got rich by exploiting Taíno labor

Ponce de León received great praise for subduing the Taíno rebellion in Higüey. According to historian Robert Fuson, the government rewarded him with a large estate on the Yuma river, as well as a "repartimiento" — a group of Native American slaves who would work his land for him. Furthermore, Governor Ovando was so impressed that he appointed Ponce de León the "frontier governor" of the province of Higüey.

On his Higüey estate, Ponce de León ordered his new slaves to grow yucca and sweet potatoes, raise pigs and cattle, and produce a variety of other foodstuffs. Higüey's important placement on the far east of Hispaniola meant that the province was the final stop for many Spanish ships before their long voyage back across the Atlantic. So, naturally, Ponce de León's goods were in high demand.

Juan Ponce de León prospered. With his newfound wealth, he started a family with a woman named Leonora. In 1505, Ponce de León received permission to found a new town in Higüey: Salvaleón. There, his large stone house still stands to this day.

Juan Ponce de León began the colonization of Puerto Rico

Even with his prosperous estate, Juan Ponce de León still wanted to increase his wealth further. And, like many Spanish explorers, there was one shiny thing on his mind: gold.

As governor of Higüey, Ponce de León was often visited by Taínos from the neighboring island of Puerto Rico (referred to by the Spanish as "San Juan Bautista" at the time). These Taínos told Ponce de León about the fertile soil and abundant gold that could be found in Puerto Rico, per the research of historian Robert Fuson. Unable to resist the idea of a gold-rich island less than 100 miles to his east, Ponce de León petitioned the King of Spain to allow him to conduct an expedition to Puerto Rico, which Spain had not yet formally attempted. In 1508, King Ferdinand agreed. (Ponce de León may have already gone on an off-the-books exploratory mission before receiving the King's permission, though.)

As David Marley explains, Juan Ponce de León and his team of roughly 50 men docked near modern-day San Juan in August of 1508. As told by the Encyclopedia Britannica, the group founded Puerto Rico's oldest colonial settlement, Caparra, which is now the oldest known European community in the modern United States. During their stay on the island, the expeditionary force spent most of their time searching for gold; they were met with some success, but returned to Hispaniola a few months later when supplies ran low.

Ponce de León expanded Spain's enslavement of Indigenous peoples

Just as Governor Nicolás de Ovando had been impressed by Juan Ponce de León's crackdown on the Taíno rebellion, so too was he excited by the explorer's journey to Puerto Rico. As a result, Ovando appointed Ponce de León to be the new governor of Puerto Rico, a huge promotion from his prior role in Higüey. King Ferdinand soon confirmed this appointment and ordered Ponce de León to start colonizing the island in earnest — in particular, to obtain more gold for the empire. Ponce de León complied and returned to Puerto Rico with his family in late 1509.

But, as you can expect, Juan Ponce de León was not a benevolent leader for the island. As early-20th century historian Rudolph Van Middeldyk writes, Ponce de León quickly began enslaving the Taíno people of Puerto Rico. He distributed the enslaved Taínos among his men, further entrenching Spain's "repartimiento" system that had benefited him back in Higüey. These slaves would be forced into a variety of jobs, from gold mining to farming.

Furthermore, the Encyclopedia Britannica explains that unenslaved Taínos were still expected to pay tribute to Spain in the form of crops and gold. Some were also forced to adopt Christianity. At the same time, European diseases ravaged Indigenous communities. The Taíno population underwent a severe decline during Juan Ponce de León's rule.

Ponce de León crushed a second rebellion in Puerto Rico

As Juan Ponce de León tightened Spain's colonial stranglehold on the island of Puerto Rico, some Taínos decided that enough was enough. Rudolph Van Middeldyk provides an account of how the subsequent rebellion likely unfolded. It began in early 1511 when a cacique — or Native leader — named Guaybána convinced neighboring caciques to lead attacks on the Spaniards living near their respective villages. Many caciques were hesitant, aware of the destructive power of Spanish weaponry, but the majority ultimately agreed. By June of 1511, a sizable portion of the Taíno population was in open rebellion.

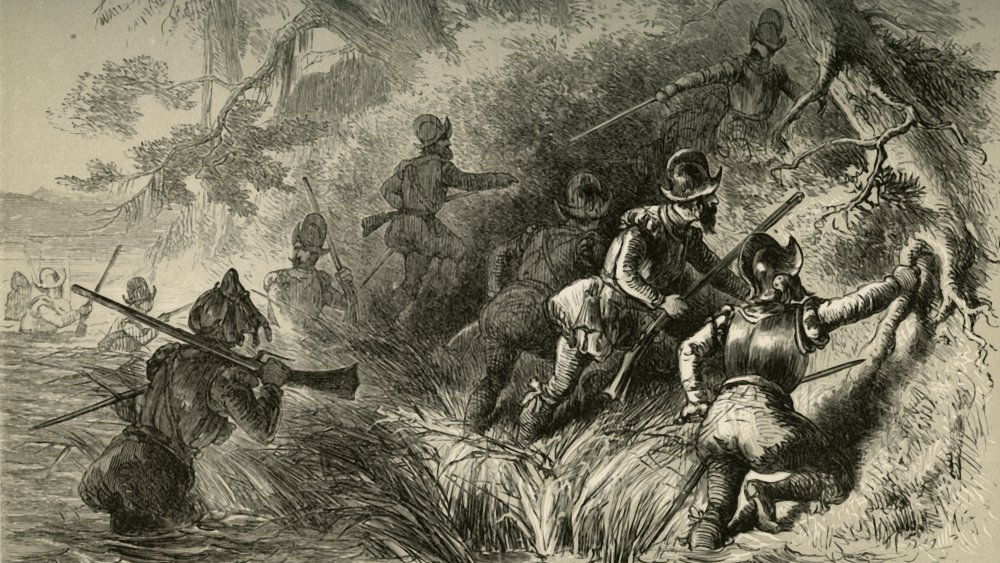

Casualties quickly piled up on both sides. The Taínos attacked Spaniards with arrows and burned down their settlements, while the Spanish retaliated with swords and gunfire. Ponce de León hoped to bring a swift end to the rebellion and mobilized a force of about 120 men. But the Taíno force — with reinforcements from the Carib tribe — numbered in the thousands.

In a late-night sneak attack, Juan Ponce de León's men killed around 150 Native Americans with zero casualties on their side. The fighting would continue in this manner for some time, with the Spanish relying heavily on long-distance gunfire to kill their enemies one-by-one. The cacique Guaybána was one of the men killed by Spanish gunfire, which demoralized the Taínos, and the rebellion quickly collapsed. According to Van Middeldyk, "no other cacique ever attempted an organized resistance, and the partial uprisings that took place for years afterward were easily suppressed."

Juan Ponce de León had a political feud with the son of Christopher Columbus

While Juan Ponce de León's brutal rule was being challenged by the native people of Puerto Rico, he also faced opposition among his fellow Europeans. Specifically, Ponce de León got into a heated political battle with Diego Columbus, son of Christopher Columbus. Christopher Columbus' contract with the Spanish Crown had stipulated that when he died, all his titles and privileges would pass to his heir. When Columbus did die in 1506, Spanish courts upheld Diego Columbus' right to inherit his father's titles, per historian John L. Kessell.

So, in 1509, Diego Columbus replaced Nicolás de Ovando as governor of Hispaniola. With his newfound power, Columbus attempted to institute new leadership for the island of Puerto Rico as well — leadership that would be loyal to him. As Rudolph Van Middeldyk wrote, Diego Columbus "deposed Ponce and appointed Juan Ceron as governor in his place." When King Ferdinand heard about this, he was outraged and demanded that Juan Ponce de León be reinstated as governor. The King's decree was upheld, and Juan Ceron was arrested and returned to Spain.

The feud between Diego Columbus and Juan Ponce de León continued for several years. But, even though Ponce de León had the King on his side, he would ultimately lose. By late 1511, according to Robert Fuson, Columbus was able to consolidate enough power to have Juan Ceron reinstated as governor of Puerto Rico. This time, Ponce de León would be removed for good.

Ponce de León brought Florida into the Spanish empire

After Juan Ponce de León had officially been ousted as governor of Puerto Rico, King Ferdinand took pity on him. He recommended that Ponce de León continue exploring the New World on behalf of Spain — in particular, to search for the yet-unexplored "Islands of Benimy." Ponce de León agreed. His generous contract with the Crown promised that he could keep a sizable percent of the riches he found, and would even be appointed governor for life of any new lands he discovered.

So, in 1513, Ponce de León set sail with three ships of roughly 200 men, traveling northwest from Puerto Rico, as told by Biography. For a month, they passed the many already-explored islands of the Bahamas. Then, on April 2nd, 1513, they spotted land which appeared to be a much bigger island. Ponce de León named it "La Florida," in honor of the Easter season, which Spaniards called "Pascua Florida," per History. The men would later discover that they had stumbled upon a peninsula attached to a massive continent — somewhere along the eastern coast of modern-day Florida.

Ponce de León immediately claimed this new land on behalf of Spain. So, after Puerto Rico, Florida became the second territory in which Juan Ponce de León personally ushered in the era of Spanish colonization. Just as it had in Puerto Rico, Spanish rule would prove devastating to Florida's Native inhabitants.

Ponce de León fought with the Native tribes of Florida

Juan Ponce de León and his men continued sailing along the coast of Florida, occasionally docking to explore further inland. During these trips, they encountered a number of Native tribes, including the Tequesta and the Calusa. Most of these initial meetings were tense but non-violent; according to a 1601 account of the mission by Spanish historian Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, Ponce de León "wanted to establish a good first impression."

But the explorer soon abandoned his nonviolent façade. On June 3rd, an attempt to trade with the Calusa tribe went awry. According to Herrera, some Calusa tribesmen paddled out in their canoes and began to seize the anchor cables of one of Ponce de León's ships, perhaps in an attempt to prevent the Spaniards from leaving. In response, Ponce de León's men captured four Calusa women and smashed two of the tribe's canoes. The next day, the Calusa retaliated by sending many more canoes to surround the Spanish vessels, leading to a full-on battle. One Spaniard and several Calusa were killed in the fight, and four more Calusa were captured.

This battle was just one of Juan Ponce de León's several destructive encounters with the Native tribes during his initial exploration of Florida. It foreshadowed his own violent death eight years later.

Juan Ponce de León sought land and riches — not a Fountain of Youth

It should be said that Juan Ponce de León was greedy and status-obsessed, but he was not stupid. Legend has it that Ponce de León stumbled across Florida in his search for a mythical "Fountain of Youth" — a water source that could reverse the aging of anyone who found it. But most historians agree that this is a complete fabrication.

Even so, the legend has an interesting history. According to History, the Fountain of Youth first became associated with Ponce de León in 1535 — over a decade after his death — due to the writings of Spanish historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. The Smithsonian Magazine reports that Oviedo was an ally of Diego Columbus, making him an enemy of Ponce de León, so he sought to use his writing to discredit the explorer's legacy. By suggesting that Ponce de León was searching for a youth-restoring fountain, Oviedo was hoping to imply that Ponce de León was old, weak, and impotent. And his strategy worked, more or less. After 1535, a number of other Spanish historians picked up the story, until eventually, Juan Ponce de León's name became synonymous with the foolish and self-obsessed hunt for an imaginary fountain.

But, today, associating Ponce de León with the Fountain of Youth covers up the grim truth: the Spaniards were hunting for gold, land, and slaves, not some nonsensical myth.

Juan Ponce de León was ordered to subdue the Caribs

After over half a year of exploring Florida in 1513, Juan Ponce de León returned to Puerto Rico — but Caparra, the settlement he had founded, was in ruins. According to Robert Fuson, it had been attacked by a group of Caribs — a prominent tribe in the Caribbean. The Caribs had burned down much of Caparra and killed a number of Spaniards. Thankfully for Ponce de León, his family had escaped.

Ponce de León worried that Diego Columbus was escalating hostilities with the Native tribes, so he decided to report directly to Spain. He arrived a few months later and was proudly welcomed by King Ferdinand. To repay his service to the empire, the Crown entered a new contract with Ponce de León which reinforced his sole authority to settle and govern Florida. But there was one condition: Ponce de León must lead a naval force in battle against the Caribs, who had been persistently attacking Spanish settlements.

Juan Ponce de León agreed. With his tiny three-ship armada, the explorer sailed to the island of Guadeloupe, a Carib stronghold. But what happened next is unclear. As Robert Fuson writes, some Spanish historians have suggested that Ponce de León fled for his life after the Caribs attacked some of his men; others describe it as a tactical retreat. Either way, the attack on Guadeloupe was a failure, but there were likely other military engagements before the end of the Spanish campaign against the Caribs.

Juan Ponce de León died after a skirmish with the Calusa in Florida

King Ferdinand died in January of 1516. Because the King had been one of Juan Ponce de León's strongest supporters, the explorer felt that it was imperative that he go back to Spain in order to defend the land and titles that the Crown had given him. After two years in Spain, per Biography, Ponce de León was relatively confident that his titles would be upheld, so he returned to his family in Puerto Rico. By that time, there had been several unauthorized attempts to settle in Florida, but each group of Spaniards had been expelled by Calusa warriors. So, in order to claim what was "rightfully" his, Ponce de León decided that he must finally usher in the permanent colonization of Florida.

But Ponce de León's settlement attempt suffered the same fate that the previous ones had. As History.com explains, Ponce de León's colonizing expedition of roughly 200 people landed in southwest Florida in early 1521. But, before they could establish a settlement, they were attacked by the Calusa tribe. During the attack, Juan Ponce de León was mortally wounded by a possibly-poisoned arrow, and his men were forced to retreat. The expeditionary force sailed to Havana, Cuba, where Ponce de León died shortly after, ending his turbulent career.

It was not until 1565 — over four decades later — that Spain was finally able to construct a permanent settlement in Florida.