Mysteries Of The Sistine Chapel Revealed

For visitors to Vatican City, the tiny nation located in the middle of Rome, there are a few sights that you simply must see. They're mostly religious places, of course, since the Vatican is ruled by the pope and the Catholic Church. The cultural wonders include the Vatican Museums, St. Peter's Basilica, and the Apostolic Palace. However, one of the most consistently packed places here is the small Sistine Chapel.

Ostensibly the private chapel of the pope, the Sistine Chapel is now a major attraction that's also packed with over five centuries of art history, says Smithsonian Magazine. During the Renaissance, a series of popes commissioned artists to decorate the chapel, making it a monument to the Church, the earthly skill of the artisans, and the depth of the papal checking account. Though he didn't work alone, Michelangelo Buonarroti gets most of the acclaim for the Renaissance treasures of the chapel. But, before you get too comfortable, know that there are quite a few twists to this story. Michelangelo, along with other great minds of his day, didn't always fall in line. He frequently butted heads with fellow artists and made Church officials uncomfortable.

Once he completed the frescoes, however, that was it. Right? Now that we've had a few centuries to contemplate his and others' work inside the chapel, some historians are starting to wonder if there are some vital clues that almost everyone has missed. From hidden messages to little-told stories, the Sistine Chapel is rich with mysterious history.

Michelangelo was in over his head

Michelangelo was a sculptor, but he couldn't decline when Pope Julius II told him to paint the Sistine Chapel. The pope had already commissioned him to sculpt a papal tomb but hadn't paid Michelangelo and seemed to have lost interest in the project, says Khan Academy. Michelangelo was able to go back and finish the tomb eventually, but until then, he was stuck painting the ceiling of the little church.

The frescoes of the Sistine Chapel are especially tricky. The technique requires painting on wet plaster, according to Tate. Because the plaster dries quickly, artists must work quickly. If they're too slow, the paint dries and flakes off. If they get it right, the pigments merge with the plaster and become an integral part of the wall. Michelangelo, already a prickly character, did not respond well to this stressful technique. According to Michelangelo: The Sistine Chapel Ceiling, he told Piero Roselli, the master mason who prepared the ceiling, that he didn't want anything to do with the project. He was also getting older and found that the long hours spent painting on a scaffold were uncomfortable.

It was so bad that he wrote a long sonnet detailing all of his complaints, reports Slate. In it, he hyperbolically complains about goiters and crushed brains and wails that, "My painting is dead." Thankfully, he proved more tenacious than his despair and finished the project, but not without some dramatics along the way.

More than one artist worked on the Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo is the most well-known painter of the chapel, but other artists installed their own work inside the space. Pope Julius and his successors were committed to showing off their budget and art world connections.

On the north wall of the Sistine Chapel are six frescoes showing various events taken from the life of Jesus Christ, reports Britannica. These were completed by big-name artists like Sandro Botticelli and Domenico Ghirlandaio, among others. Turn around to the south wall, and you'll see a further six frescoes showing the life of Moses. Pietro Perugino, Luca Signorelli, Cosimo Rosselli, Botticelli, and more contributed to these artworks.

Even Raphael, the young artist and sometimes rival of Michelangelo, appears here, but only on rare occasions, says Smithsonian Magazine. That's because Raphael designed a series of tapestries that used to hang on the walls, commissioned by Pope Leo X in 1515. Because textiles are especially delicate and these tapestries are more than four centuries old, they're rarely displayed in the chapel anymore. The ten large tapestries and two border pieces were unveiled in late 1519, mere months before Raphael died suddenly at just 37 years old.

The figure of God looks weirdly familiar

In most interpretations of Christian theology, God the Father doesn't have a set human form. It makes sense, given that God is supposed to be an all-knowing, all-powerful deity that's only barely understood by humanity.

That may be all well and good for theologists, but it's presented a serious problem for artists throughout human history. Medieval and Renaissance artists were especially stuck, since so much of their best-paying work was commissioned for religious purposes, like altarpieces and the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo skirted this issue somewhat by depicting God as a stern, bearded man. The look is heavily inspired by previous art of Jupiter, king of the Roman gods. Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling maintains that Michelangelo was clearly taking cues from classical statuary throughout Rome, along with medieval examples of God in human form. All the same, his depiction of God was still new enough that it caused some embarrassing gaffes. Once it was all unveiled, Bishop Giovio, by all accounts an intelligent Church man, at first couldn't figure out who the old guy on all the Old Testament frescoes was supposed to be.

Is there a human brain on the ceiling?

In the fresco known as The Creation of Adam, God is shown forming the first human, accompanied by a bunch of spirits. It's a dramatic composition, with Adam reaching up from the ground out of oblivion. He's almost touching a stormy-looking God, who is himself surrounded by swirling fabric and heavenly spirits. It's a famous composition, but is there a hidden medical image right here that's gone undetected for centuries?

In 1990, F.L. Meshberger wrote in the Journal of the American Medical Association that this image of God giving intelligence to Adam shows a side view of a human brain. Squint, and you might see it. Another idea claims that a different fresco which shows God's throat also depicts a different view of the brain stem, reports Scientific American. Plenty of scientists and religious officials took issue with this out-there theory. As quoted in The New York Times, Dr. Kathleen Brandt said that, "God is more than a flying brain."

Though these theories sound pretty wild, there's actually some evidence to back them up. Judging by Michelangelo's mastery of anatomy, he was pretty familiar with the human body. He almost certainly participated in dissections, says the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. That extracurricular activity would have been kept quiet thanks to condemnation from religious authorities. Despite the secrecy, Michelangelo almost certainly knew what a brain looked like and maybe, just maybe, hid one or two in the chapel paintings.

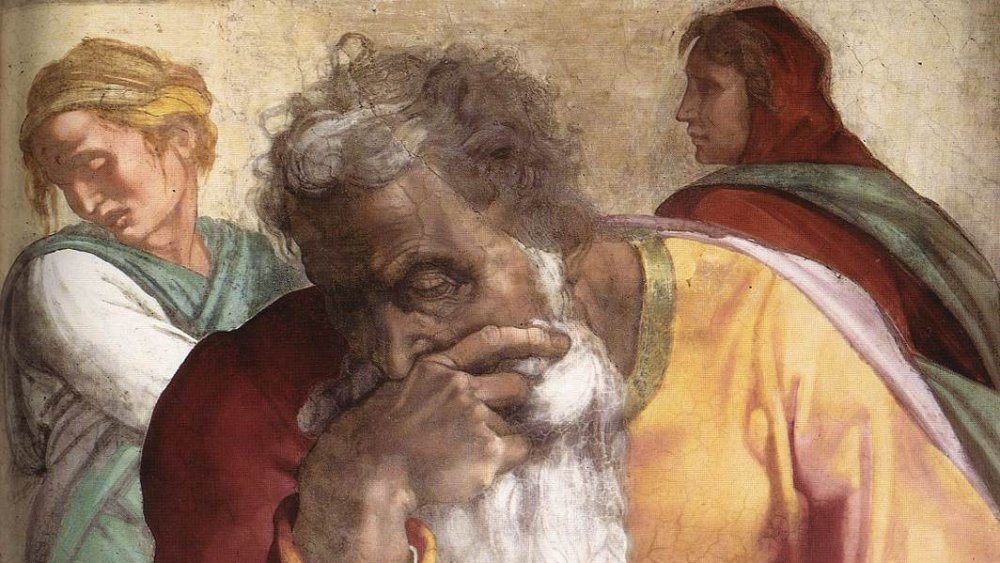

Portraits of women make some reconsider Michelangelo's sexuality

Brilliant as he was, Michelangelo often appeared to use male models even when he was supposed to be painting women. That wasn't an uncommon practice at the time, but some details still seem strange. A later sculpture, the allegorical Night on Giuliano de' Medici's 1531 tomb, is meant to show a female figure. Yet, it looks an awful lot like a muscular man with some feminine features plopped on top of the chest. Why would an artist known as a master draftsman of the human form get it so wrong?

The depictions of muscular women in the Sistine Chapel have led some to wonder if Michelangelo was hinting at his own sexuality. The evidence here is pretty thin on the ground, given that 16th-century Italy was hardly an affirming place for LGBTQ people. Homophobia: A History notes that in 1532, the Holy Roman Empire made sodomy a crime punishable by death. If Michelangelo was attracted to men, he would have kept very quiet about it.

However, historians have noted a few hints that the perpetual bachelor may not have been entirely straight. For one, he appears to have fallen in love with Tommaso de' Cavalieri, a Roman noble, says Michelangeo and the Pope's Ceiling. Likewise, some historians and sources like The Metropolitan Museum of Art maintain that Michelangelo's passions were an open secret.

Some think there's a hidden feminist message inside

Some people believe that Michelangelo's frescoes show hidden biological female organs and, therefore, a coded feminist message. Is there any truth to this rather wild idea?

Much of the theory, published in the peer-reviewed journal Clinical Anatomy, has to do with ram skulls and upside down triangles. The ram horns may represent the shape of Fallopian tubes, with the rest of the skull filling in for the remaining reproductive organs. The triangles may also refer to other shapes common in female anatomy. Others claim that the triangles point toward women in the frescoes. Oh, and all those muscular women? They weren't male models with feminine bits added on but instead depictions of strong Biblical women.

It's all a bit much for other art historians. Triangles, for instance, aren't exactly a smoking gun from Michelangelo, secret feminist. They could have simply been a decorative flourish. Other publications, like The Guardian, have gone so far as to call the whole idea "daft." It doesn't acknowledge the fact that Michelangelo worked within a highly patriarchal society and wouldn't have easily become a modern-style champion of women's rights. Meanwhile, few understood what the uterus actually looked like until the 1530s. That's when Gabriel Fallopius, Italian anatomist, described the structure of what we now call the Fallopian tubes, says Britannica. Michelangelo completed his work on the Sistine Chapel in 1512.

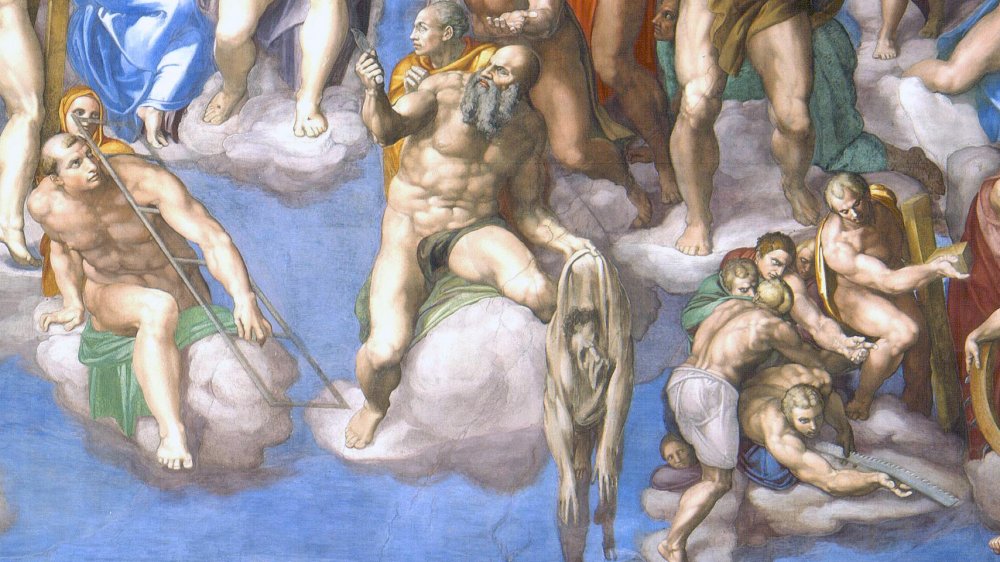

The Last Judgement is supposed to be read in a ring shape

The huge fresco behind the chapel's altar, The Last Judgement, was also painted by Michelangelo. Though it's by the same artist in the same space, this fresco was completed in 1541, more than 25 years after Michelangelo had finished the ceiling frescoes in the chapel, according to the Vatican Museums. At the time, Michelangelo would have been 67, older and more tired than when he had first run up against the difficulties of painting in the chapel.

Though Michelangelo wasn't really afraid to break with religious views of his time, he stuck with some traditions for this monumental work. Like in other paintings of the Christian Last Judgement, says Khan Academy, you're supposed to read the piece in a ring shape. Though it's a massive artwork with over 300 figures twisting and turning within your field of vision, there's a method to understanding it that will make its seeming chaos clear.

Generally speaking, the souls of the saved rise up to Heaven on the left, helped along by friendly angels. On the right, the damned fall down on their way to Hell, also helped on their path by somewhat less friendly demons. The whole composition rotates around the figures of Jesus and Mary in the middle, with Jesus taking center stage as a muscular, avenging God.

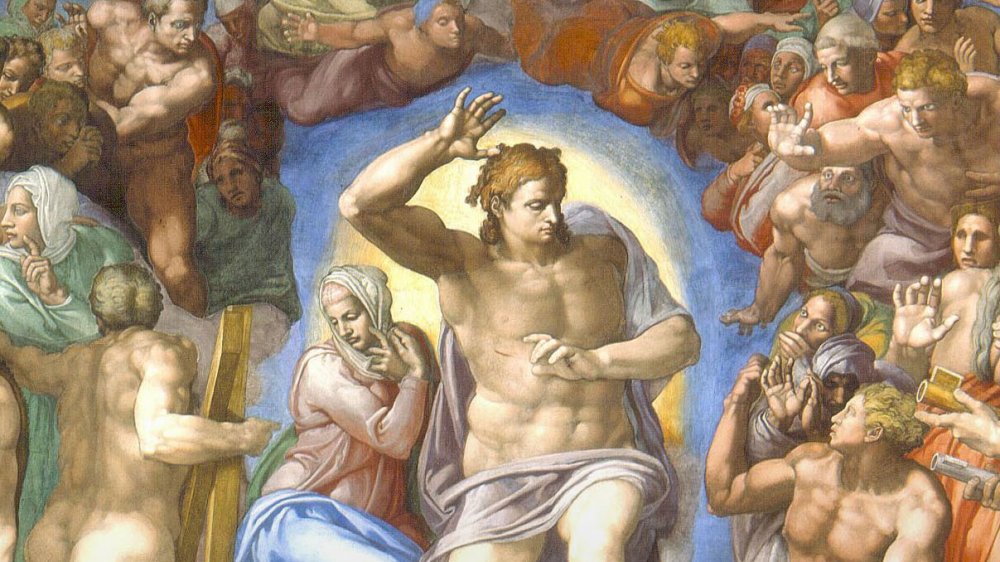

The Christ figure in The Last Judgment is extra weird

Most Renaissance depictions of Christ show a rather slender, bearded man, busy being merciful or gently blessing people, with a few horrifying crucifixion scenes thrown in. For Michelangelo, who wanted to create a depiction of the apocalyptic Last Judgement, he needed a figure who wasn't just a gentle shepherd. He needed an angry avenger.

Take one look at the image of Christ in The Last Judgement, and you'll begin to understand what Michelangelo was trying to achieve. Here, Jesus is muscular, angry, and ... beardless? The longer you look, says Art in America, the more you see how this fresco really deviates from the Renaissance norm. It's not just the fact that Jesus is shown as an avenging deity rather than a bringer of peace. He also looks almost pagan, as if he were inspired by earlier statues of Apollo, the sun god worshipped by the Greeks and Romans.

He's not alone. Other pagan or pagan-inspired figures pop up in the very same artwork. There's Charon at the lower right, who ferries the ancient dead across the rivers of the underworld. Biagio da Cesena, a vocal critic of Michelangelo's work, also appears in Hell as Minos, judge of the dead, says Source: Notes in the History of Art. Da Cesena, who would later become papal master of ceremonies, didn't appreciate the cameo.

Michelangelo hid a self-portrait in The Last Supper

On the right side of The Last Judgement, looking up at the central figure of Christ, sits Saint Bartholomew. As with many Catholic saints who were martyred for their faith, Bartholomew displays a significant image relating back to his specific torture. In this case, it's especially disturbing. Bartholomew, says Britannica, was said to have been skinned while still alive.

In The Last Judgement, he's still mercifully got his own covering. Bartholomew can be seen holding not only the knife that was used to flay him but a grotesquely empty human skin. If you can bear to look closer at the uninhabited skin, you might start to ask some interesting questions. To start, the empty skin doesn't look anything like Saint Bartholomew as he was painted by Michelangelo. Where the fresco shows a live man with a bald head and a full, gray beard, the empty husk shows a full head of hair. They simply look like different people. So, if that's not Bartholomew, then who is it?

The Journal of Medicine and Life reports that Dr. Francesco La Cava believed that this was Michelangelo himself. It kind of makes sense if you refer to portraits of the dark-haired Michelangelo, though you have to do a bit of squinting to make it work. Nowadays, most art historians are convinced that Michelangelo included a cheeky but gross self-portrait in The Last Judgement.

The paintings contain shocking deviations from Catholic theology

For all of the supposedly hidden messages in the frescoes, Michelangelo's departure from then-current Catholic thought was the most obvious and controversial for some observers. These changes were so upsetting to some that the very future of the fresco was in question.

There's the angry-looking Christ figure at the center of The Last Judgement, who doesn't necessarily jibe well with the redeemer image so beloved by other artists. Art in America maintains that Christ's intentions could have been worryingly obscure for Renaissance observers. Is he really angry? Could it be some other, deeper, unknowable expression? Furthermore, other figures don't line up with established notions. The Virgin Mary, sitting right next to her son, is barely noticeable. To some, she looks frightened and far from glorious, as others thought she should be seen.

Some details may surprise you. It's easy to understand how things like pagan influences might catch the eye of Michelangelo's critics, but what about figs? Back in the ceiling frescoes, the "Temptation" panel shows Adam and Eve succumbing to the serpent's enticement. They're pulling fig fruit off the Tree of Knowledge. According to Atlas Obscura, the prevailing Catholic thought maintained that the fruit in question was an apple. By including figs, a notion more inspired by Jewish interpretations of the Old Testament, Michelangelo was deviating from the norm yet again.

The Last Judgement was considered shockingly naughty

When the Last Judgement was completed, Biagio da Cesena, the pope's eventual master of ceremonies, was shocked to see so many nude figures inside a religious building. He wasn't alone. Even though nudity in art wasn't such a big deal earlier, says the journal Renaissance Review, authorities had become more and more prudish by Michelangelo's time. Seeing the bare bottoms and other parts of saints and sinners alike was genuinely shocking for many.

Even Michelangelo's earlier sculpture, the now-ultra-famous David, completed in 1504, made Church officials' eyes bug out. Shortly after the statue's unveiling, its privates were covered up with bronze fig leaves, according to Artsy. Toward the end of Michelangelo's life, the Church took things even further and began a campaign to abolish any hint of lust in art. The resulting "fig leaf campaign" soon came for The Last Judgement.

Artist Daniele da Volterra was later brought in to paint drapery over the offending parts. According to Britannica, he was actually a friend of Michelangelo who took many cues from the master's work. It's ironic that, in 1559, Pope Paul IV told Volterra to add in convenient drapery over the nude figures in The Last Judgement. Volterra's work earned him the nickname "Il Braghettone," or "The Breeches-Maker."

The Sistine Chapel got seriously filthy

Thanks to soot from candles, vintage restoration attempts, and the passage of time, the art in the Sistine Chapel eventually became so dirty that it was hard to see it. Throughout that time, many different artists and officials had tried to maintain the frescoes and other artworks inside, with uneven results.

In 1625, Simone Lagi wiped down the ceiling with clothes and pieces of bread, says ARTnews. He claimed that there was no harm to the frescoes, but the sort of elbow grease he must have used would probably make a modern conservator faint in shock. There's also speculation that Lagi used a varnish that, in time, turned the artwork brown and further obscured it.

A massive restoration project cleaned things up from 1980 to 1994, but the cleaning elicited much controversy. Some critics, reports Oberlin Alumni Magazine, were worried about over-restoration that could damage Michelangelo's work. They argued that conservation, maintaining the work in its present state no matter how dirty, was better. They were overruled, and more invasive restoration techniques were used instead. Eventually, most reporters and critics came around to the restoration. Centuries of grease and soot were gently washed away, revealing the artworks beneath. While critiques remain, the renewed frescoes are still very popular and now easier to see. As reported by the BBC, continuous cleaning work will hopefully keep the art from ever getting that dirty again.