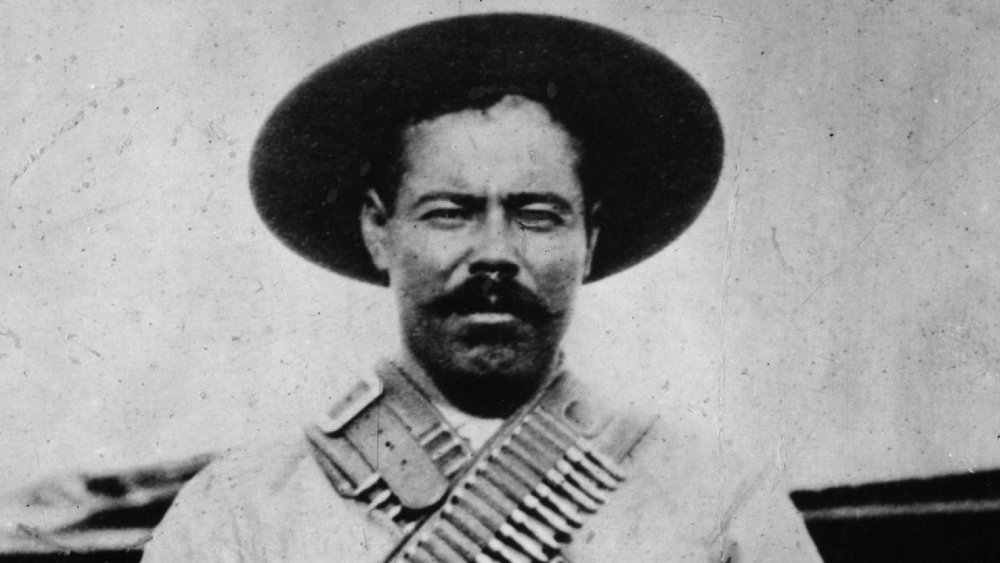

The Untold Truth Of Pancho Villa

Considering there's no real evidence for one singular individual named Robin Hood, gathering a semi-military following to commit banditry (all for a good cause — robbing from rich, giving to poor, blah blah blah), it's amazing how many figures in history are described as being, well, like Robin Hood. Jesse James gets that (it wasn't true), and so did Butch Cassidy (probably not, but at least he didn't kill people), and the gangsters of the 1930s (not a lot). And even Doroteo Arango, known later as Francisco "Pancho" Villa. The difference is that Villa really did grow up poor and had a genuine concern for the poor of Mexico, the people of the land.

Like all of the others above, Villa is seen either as a revolutionary, fighting for justice and economic opportunity on behalf of the poor, or he's a bloodthirsty, borderline psychotic killer. The truth is in there, somewhere, and like all of us, Villa was more than just a simple descriptive phrase. Sometimes heroic, sometimes violent; sometimes altruistic, sometimes self-aggrandizing. And legendary.

He was born in 1878 into poverty, the son of poor farmers, says Encyclopedia Britannica. When Doroteo was 15 his father died, making the future Pancho the head of the family.

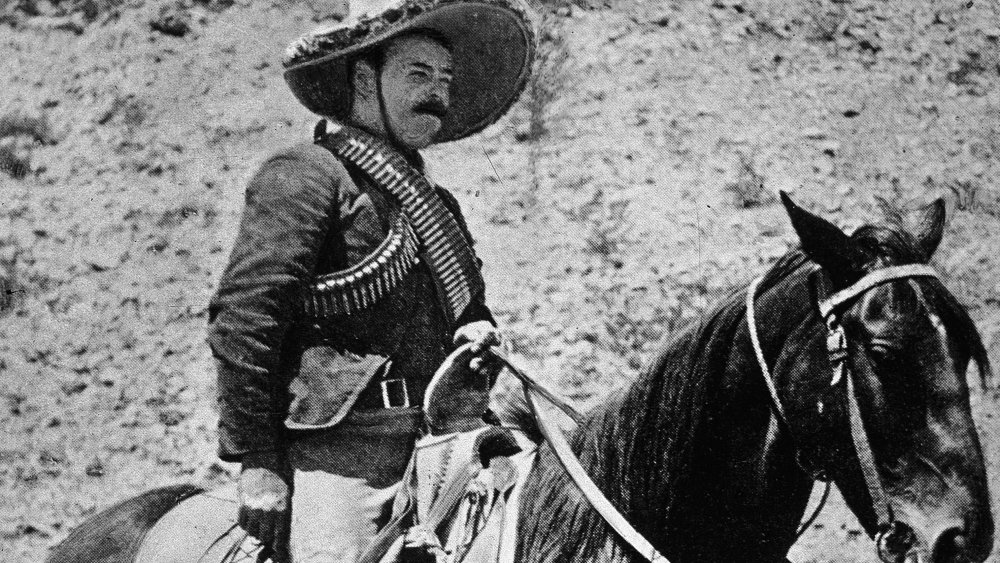

Villa moved from banditry to revolution

When a man harassed his sister, Doroteo killed him, then fled into the mountains and changed his name. Captured, he escaped, and seems to have joined with other bandits in the mountains for a time. And then the winds of revolution started to blow through Mexico. He joined forces with Francisco Madero in a successful revolt against the government, but a coup put a dictator, Victoriano Huerta, in power, according to Biography. Villa formed his own army, joining forces with Emiliano Zapata and Venustiano Carranza. Together they controlled the northern reaches of Mexico. Eventually there was a three-way struggle for control of Mexico: Villa, Huerta, and Carranza.

The U.S. government supported Villa for a time, but that was withdrawn and Villa raided the town of Columbus, New Mexico, in retaliation, reports another article on History, resulting in the deaths of U.S. Citizens. In 1916 the U.S. sent a military force after Villa — one of the young officers was George S. Patton, who saw his first combat during the mission — but failed to catch the revolutionary. The outbreak of World War I meant the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the border in 1917.

Villa lived in violent times

The clash saw the first use of automobiles in combat, and was an early example of embedded journalism. Newsreels were short, silent films with subtitles, played as part of the evening's entertainment in burgeoning movie theaters. As Smithsonian reports, Villa struck a deal with Mutual Films: the company would film battles as they happened. There are legends about the contract — if the crew missed a shot, Villa would re-create the battle; attacks would be postponed in order to take advantage of better light. According to one of Villa's biographers, Friedrich Katz, the contract merely specified that "the Mutual Film Company was granted exclusive rights to film Villa's troops in battle, and that Villa would receive 20 percent of all revenues that the films produced." According to True West Magazine, the film was made, but failed at the box office; American audiences didn't think the movie was "realistic" enough.

Villa actually had a vision for life in post-revolution Mexico. How Stuff Works quotes Alejandro Quintana, associate professor of history at St. John's University in Queens, New York, who says that Villa "envisioned a new social order in which workers could organize in communes to be in charge of the economy, eliminating the need for the upper class. There would be no military, but workers would receive military training that would help them protect themselves and acquire the required discipline to succeed. This was not communism, but a utopian [way] of life in the frontier."

Villa was assassinated when he was 45 years old

Although he had evaded American troops, Villa's own forces were scattered as a result. After a series of losses, Villa retired to the mountains where he'd fled as a young man. He lived in a collective, with families and a few followers, as John Mason Hart, Moores professor of history at the University of Houston, told How Stuff Works. Of course, there are stories of Villa's hidden cache of gold somewhere in the mountains, but it's never been found. He had at least seven wives over the course of his life; perhaps as many as 75.

On July 20, 1923, Villa was driving home with a few friends when seven men opened fire. Villa died in the assassination, struck by 16 bullets, reports True West. He was 45 years old.

Hero or villain? Revolutionary or opportunistic bandit? As Marshall Trimble, official historian of Arizona, wrote, "Pancho Villa was the 'Good, Bad and the Ugly,' all rolled into one. Like others of his ilk, Villa was a product of his time, and should be judged that way."