The Remarkable True Story Of The Pony Express

When we think of the settling of the American West, we probably think of things like railroads, and cattle, and cowboys. Reruns of Gunsmoke, and wide-open spaces, and horses. At least as important as any of those things, in one form or another, is the humble wire.

It was barbed wire that provided cheap, fast, durable fencing of property, ending those wide-open spaces and creating some semblance of order from the wilderness of the plains and the prairies and, depending on your viewpoint, putting a nail in the coffin of the open range. But it was the transcontinental telegraph wire, completed in 1861, that not only allowed one side of the country to speak immediately (sort of) with the other, but put the final nail in yet another coffin: the Pony Express.

The Pony Express — officially, the Central Overland California and Pike's Peak Express Company, which we can all agree lacks a certain snap — has been romanticized until, like a lot of the Old West, it would be pretty much unrecognizable to anybody who was involved at the time. The first culprit would be Buffalo Bill Cody, who included a demonstration (of sorts) of the Express as part of his touring Wild West shows, a sort of mixture of dramatic rodeo and outdoor vaudeville. Cody's legend included a stint on the Pony Express in his younger days, though like everything else, that's hotly debated by people who like to heatedly debate such things.

The riders were young and lightweight

Like a lot of American history, the Pony Express was a business proposition. It was a logical extension of how communication was conducted in mid-19th Century America: usually written, on paper, and those pieces of paper transported in some fashion from one point to another. Whether it was involved a courier, or a train, or a wagon, the Post was the most efficient, economical, and fastest way to convey information from Point A to Point B (providing A and B were out of shouting range, of course).

That was all very well and good if you lived on the East Coast, and westward to around the Midwest, there on the edge of the frontier. After that, it was a haphazard mix of possibilities, with steamship around Cape Horn, the southern tip of Chile in South America, the most reliable way of getting word to California. Quick? Not even a little. Not even by those standards. You could send word by stagecoach, but even that meant almost a month, and between accidents, robberies, weather, and carelessness, there was no guarantee.

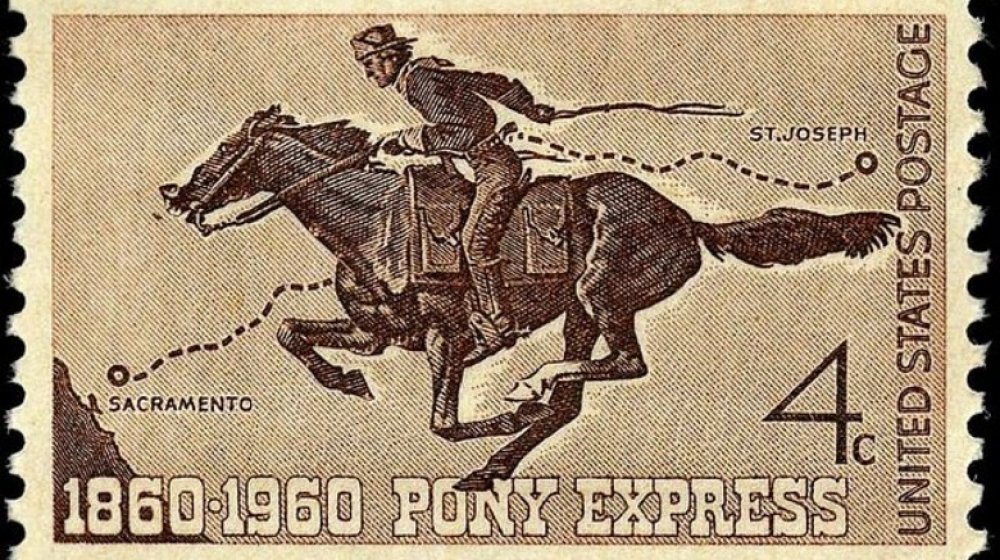

As History reports, three men — William H. Russell, William B. Waddell and Alexander Majors — came up with the idea of a chain of stations stretching across the Midwest and the mountain states, from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California — about 2,000 miles. They were the premier freighting company in the country in those days.

Speed was of the essence

The correspondence would be carried by riders — usually very young men, though as the New York Public Library posts, there's no evidence that they advertised "Orphans Preferred" — moving at top speed. The documents themselves were written on something like tissue paper. The riders transported the letters in a sort-of saddle called a mochila — more like a leather blanket with four pouches upon which they'd sit atop the horse. Stations with fresh horses were staggered about every 10 miles along the route, as Encyclopedia Britannica relates. Riders would switch horses at each station, as quickly as possible, and ride for 75-100 miles before handing off the mochila to another rider in the relay.

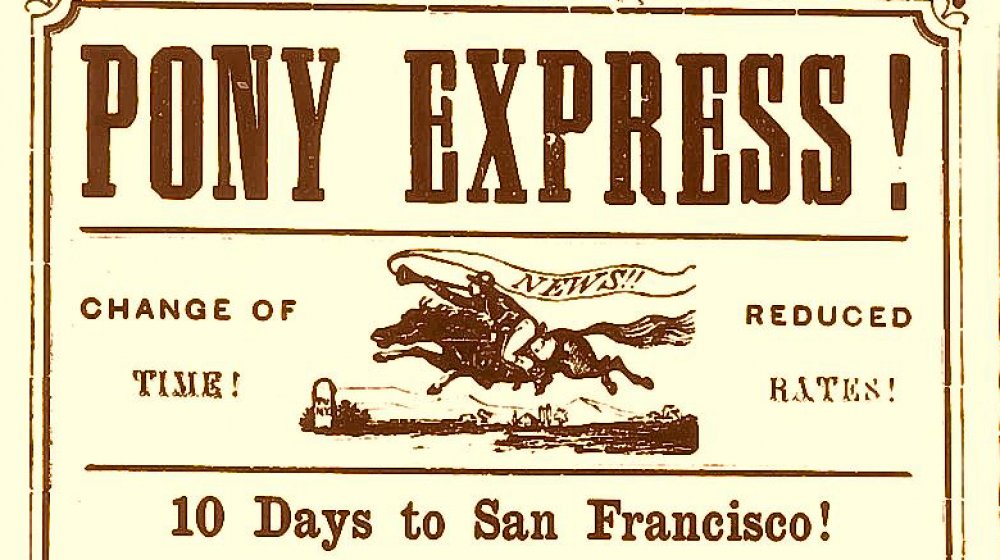

The service debuted in October 1860, and it wasn't cheap — $5 per half-ounce, payable in gold, at a time when $5 was a princely sum indeed. The service was usually utilized for government business and business business — it was far too expensive to use for a simple love letter. The issue was speedy delivery, and then as now, people paid dearly for it.

The service only lasted 18 months

The idea of a well-dressed, well-armed youngster trying to out-distance perils both human and natural, is another romantic notion that doesn't hold up, writes True West Magazine. Remember that the Express relied on speed, so every ounce counted. Mark Twain gave a description of the Express in his book Roughing It — the rider ("usually a little bit of a man, brimful of spirit and endurance," quotes the Los Angeles Times) dressed as lightly as possible in a tight-fitting jacket, a skull-cap, maybe even barefoot. No swooping cowboy hat, no buckskins, no brace of handguns. Just a teenager on a horse, riding as fast as possible over rough terrain, no matter the time of day or night, no matter the weather. In all the history of the Express, only one mail shipment was lost. Out of about 80 youngsters who served as Pony Express riders, four were killed on the job, and two froze to death, says the National Park Service.

The fastest delivery happened in March 1861. The 10-day run was accomplished in seven, to deliver the news of Lincoln's presidential inaugural address. That was shortly before the Express was put out of business by the completion of that wire — the transcontinental telegraph. The Express had always been a failing business proposition. Even with the exorbitant rates, the enterprise hemorrhaged money from the beginning. Two days after the completion of the telegraph, the Pony Express ended its run, after just 18 months in business.