The Tragic History Of The Search For The Fountain Of Youth

Perhaps nothing has vexed humanity quite like the inevitable pull of aging. We are gripped by an absurd paradox: As we grow wiser with years of experience, our bodies begin to sag, weaken, and stiffen. "Life would be infinitely happier if we could only be born at the age of eighty and gradually approach eighteen," writer Mark Twain once joked.

So, we've rushed to design workarounds to retain our youth as we age: fish oils purporting longevity, creams that will flatten out wrinkles, and human growth hormone injections to stave off decay. However, before modern science intervened, many cultures sought another source to cure ills and revitalize the body. While some alchemists worked to create an elixir of life, explorers ventured into uncharted territories to source a body of water that could turn back biological clocks. This age-defying water was called the Fountain of Youth and, sometimes, the Well of Life.

But how seriously did cultures throughout history take their quests for curing waters? Here is the perplexing, sometimes tragic history of the search for the real Fountain of Youth. Spoiler alert: Nobody has ever found it, but there were some decent contenders.

The powers of the Fountain of Youth

Across cultural representations, the mythical Fountain of Youth is said to possess the power of curing sickness or restoring the youth of those who bathe in or drink its waters. Throughout historical documents and myths, these magical waters are sometimes characterized as a spring, waterfall, well, or pool — it varies. Some of these eternal waters are floral-scented, and others are described as sulfuric from their mineral-rich contents.

As the Our Fake History podcast notes, water iconography often indicates restoration or awakening. In Christianity, religious baptisms represent spiritual rebirth, and in Hinduism, bathing in the Ganges River cleanses the soul and washes away sins. It's only natural that water sources, like a fountain, became symbols of rebirth and immortality in the global consciousness. "You could trace that up until today," Virginia Commonwealth University professor Ryan K. Smith told History. "People are still touting miracle cures and miracle waters."

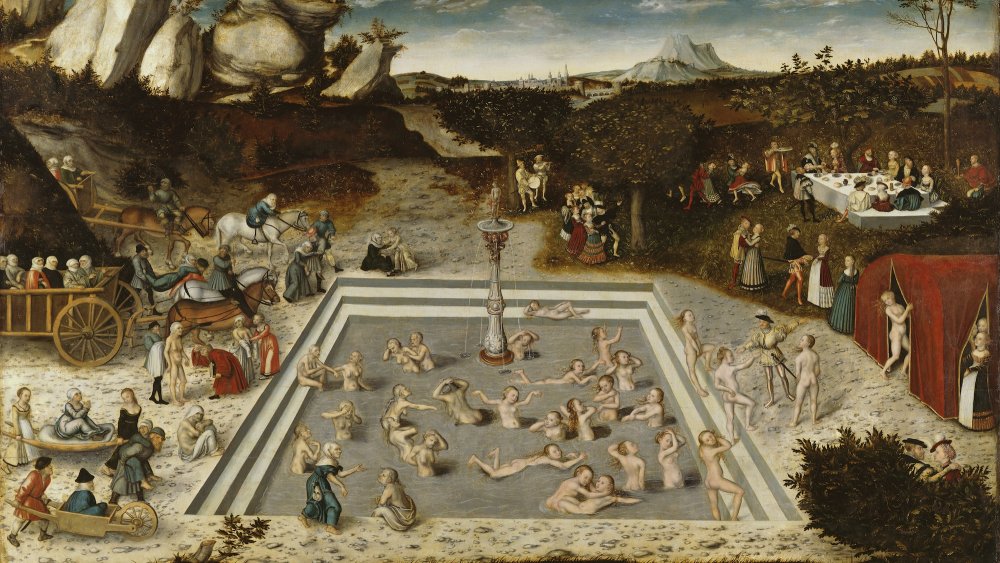

Fountains of youth made appearances in art through the centuries. French ivory carvings from the 14th century depict an old bearded man entering magical waters where young, amorous couples bathe. A 1546 painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder portrays a fountain in which the aged enter on the left and exit lithe and young on the right. These images were lifted from European romance literature of the medieval period and boomed throughout the age of colonization and exploration.

A fountain of youth in Ethiopia

The Greek historian Herodotus, in his 425 BCE history of the Greco-Persian War, was the first to mention a fountain of youth. Herodotus wrote of Persian spies visiting an African people called the Macrobians, likely referring to ancient Ethiopians or Somalis. The king of the Macrobians purportedly attributed his people's strength to their diet of boiled meat and milk. When the Persians marveled that many Ethiopians lived to the age of 120, the king "led them to a fountain, wherein when they had washed, they found their flesh all glossy and sleek [...] and a scent came from the spring like that of violets," as reported by The Root.

In 1165, the "Letter of Prester John," a forged document, started circulating in Europe. This letter was said to be sent by a Chistrianized African king to the leader of the Byzantine Empire, detailing his great land, said to be somewhere in India or Ethiopia. Within the letter was an account of a magical fountain that turned people back to the age of 32. Prester John, the immortal priest-king of Ethiopia, and the magical waters he ruled, became an incentive for the European exploration of the African coast. In 1497, the Portuguese throne sent Vasco da Gama around the Cape of Good Hope, and in 1520, another Portuguese explorer, Don Rodrigo da Lima, reached Ethiopia. What they found was a young Ethiopian ruler named Lebna Dengel — no sign of Prester John or a violet-scented spring.

The Fountain of Youth in the Alexander Romance

An account of King Alexander III of Macedon's life was collected in Greek around 338 CE. The Alexander Romance, as these exploits came to be known, is part history, part oral tradition, and part mythology. Versions of it were translated into French, German, Middle English, Persian, Arabic, and Latin. Medieval Europeans knew these tales well, serving as the bestselling adventure epics of the day.

It is said that Alexander the Great, who died in approximately 323 BCE, was searching for a river that would heal the effects of aging on his body, per National Geographic. In later Eastern versions of the Alexander Romance, Alexander the Great and his men are searching for this water within the Land of Darkness, a place of eternal night. In another tale, after traveling within Africa, Alexander the Great and his men reached an idyllic river and camped out. His men hunted birds and fish for dinner, but when they cleaned the animals off in a nearby river, the water miraculously brought them back to life. The fish swam away, and the birds took flight. According to the Our Fake History podcast, Alexander the Great thought this must be water flowing from the Garden of Eden, issuing from it eternal life.

In yet another version translated from French, Alexander the Great comes across a fountain with sweet water that rejuvenates four times a day. Once his elderly soldiers bathed in it, they all emerged unrecognizable, having transformed into brawny 30-year-olds.

Youth-giving waters in Japan

Lafcadio Hearn collected Japanese fairy tales in 1898 and released a volume that included a story called "The Fountain of Youth." In stark contrast to the European and Middle Eastern legends that preceded it, in these folktales, the spring of life is not something one deliberately seeks.

In Hearn's version, an old woodcutter happens upon a cool, clear stream in the forest. Drinking from it, the woodcutter is astonished to find he is young again: his bald head covered in hair, his wrinkles gone. The now young woodcutter tells his wife to drink from the magical spring. He waits for his wife to return, but she never does. "For the old woman had drunk too deeply of the magical water; she had drunk herself far back beyond the time of youth into the period of speechless infancy," the story ends. This story serves as a cautionary tale encouraging moderation.

Another Japanese Fountain of Youth story comes from the eighth century in Yoro Falls (pictured above). A young man piously cares for his ailing father day after day, as Taiken Japan explains. Too poor to get his father his favorite sake, the young man instead prays for his sick father's favorite drink. Magically, the nearby Yoro waterfalls turn to sake, which the young man collects in a gourd. When the old man drinks it, he becomes instantly well and young. Empress Gensho renamed her period of reign "Yoro" after this tale of miraculous recovery.

An Indian fountain of youth

The fantastic powers of the Fountain of Youth were sometimes both curative and restorative. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville was a travel memoir dating between 1357 and 1371, with an unknown author, first appearing in French.

In the tale, Sir John visits a land in Polombe — thought to be modern-day Kollam, India. At the foot of the mountain which towers over the city is a great well that has the scent of many spices. In fact, every hour, the well takes on the aroma of a different spice. It is said that those who fast and drink from the well three times will be cured of all sickness. Men who drink often from the well never grow ill and "always seem young." "They that often drink thereof seem always young-like, and live without sickness," tells The Travels. In Polombe, this magical spring was called the "well of youth" and was thought to have its restorative powers because it flowed from the waters of Paradise itself.

Juan Ponce de León's search

No other name is as synonymous with the Fountain of Youth as Juan Ponce de León, a Spanish explorer, who, in the 16th century, was rumored to have sought a place of mystical rejuvenation. You may have even read about his fruitless search in your textbooks.

Juan Ponce de León was born into Spanish nobility around 1473. Since his first voyage alongside Christopher Columbus in 1493 to the New World, Ponce de León tied his financial prospects to colonization. He made a name for himself, first by taking part in the massacre of the Taíno people during their rebellion in 1504. Then, in 1508, King Ferdinand II gave Ponce de León permission to colonize San Juan Bautista (Puerto Rico), and he became its governor. But his governorship became vulnerable after Ponce de León clashed with Christopher Columbus' heir, Diego Columbus, who was vying for power in the West Indies, as reported by Our Fake History. So, as a sort of consolation, the king gave Juan Ponce de León a contract in 1512 to explore an island called Beniny or Beimeni. There were no mentions of the Fountain of Youth anywhere within this original contract. All you can find within the royal contract were specific orders for dividing gold and subjugating Native populations.

"What Ponce is really looking for is islands that will become part of what he hopes will be a profitable new governorship," J. Michael Francis, a history professor at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, told History.

Juan Ponce de León reaches Florida

Juan Ponce de León did not find the fabled Beimeni to lord over and enrich himself. Instead, he had personally financed three ships and 200 men in March 1513 only to find Florida. According to History, it's estimated that Ponce de León docked in Florida around April 2, 1513. He dubbed it "La Florida," as it was the Easter season or, as it's called in Spanish, "Pascua Florida." While many claimed he docked somewhere near St. Augustine, historians think it's more likely that he docked 140 miles south in what is now Melbourne, Florida. On that voyage, Ponce de León sailed through the Florida Keys, fought with the Native populations, and eventually returned to Puerto Rico.

Ponce de León still had his sights on a new colony. In 1521, he returned once again to the Florida coast, sending correspondence to both King Charles V and Pope Adrian VI that detailed his desire to settle the land, albeit with absolutely no mention of the Fountain of Youth. It was here that, in a skirmish with the indigenous people of Florida, Ponce de León was shot in the thigh by an arrowhead. He died shortly after in Cuba after the wound became infected. Naturally, Ponce de León never did find a river of immortality.

The Fountain of Youth myth is born

If Ponce de León never expressed interest in a Fountain of Youth in his writings, letters, or contracts, how did he become so well-known for his thirst for vitality? Gonzalo Fernando Oviedo y Valdés, a Spanish court chronicler, was the first person to make an explicit connection between Ponce de León and the Fountain of Youth. The link wasn't made until 14 years after Ponce de León's death. In his 1535 Historia General, Oviedo portrays Ponce de León as an old man trying to cure impotence via lapping up youth-restoring waters. Oviedo's family hated Ponce de León, and it was a story crafted to posthumously embarrass his political rival, as reported by Smithsonian Magazine.

Of course, Oviedo's claims were unsubstantiated, but they persisted for centuries in retellings of the conquistadors. In fact, all evidence points to Ponce de León being quite vital at the time of his Floridian exploration: He had fathered at least four children with his wife and was still under age 40. "He was being discredited [as] an idiot and weakling," Ryan K. Smith, a history professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, told History. "This is machismo culture in Spain at the height of the Counter-Reformation."

So, what we've all learned about Juan Ponce de León was most likely just a long-lasting insult about his performance in bed.

How the legend of the Fountain of Youth spread

From that first account, the tale picked up steam. Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, who lived with the indigenous people in Florida after being shipwrecked there, wrote in his 1575 memoir of Ponce de León's foolish search for the Fountain of Youth. Next came Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, the chief historian of the Indies, who wrote in 1596 of Ponce de León's effort to find a magical stream. Herrera wrote, "[Ponce de León] had an account of the wealth of this island (Bimini) and especially that singular Fountain that the Indians spoke of, that turned men from old men into boys," as told by ThoughtCo. Of course, none of these accounts used any primary sources.

Still, the legend of the Fountain of Youth picked up momentum after Spain ceded the state of Florida in 1819, as Legends of America notes. In 1849, the American author Washington Irving wrote a fictionalized version of Ponce de León and leaned heavily on the quest for the Fountain of Youth. Painters such as Thomas Moran depicted Ponce de León meeting with indigenous people in Florida, keeping the story alive in the public imagination.

Ryan K. Smith, a history professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, believes that the search for the Fountain of Youth goes on because of the fascination with the hunt. "People are more intrigued by the story of looking and not finding than they are by the idea that the fountain might be out there somewhere," Smith told National Geographic.

The magical land of Bimini

To this day, the island of South Bimini in the Bahamas touts a Fountain of Youth tourist destination — a well carved from limestone rock by groundwater thousands of years ago. On their website, they explain that Juan Ponce de León learned "from the Indians in the 1500s that Bimini was the site of the Fountain of Youth." It was said that the Arawaks in Hispaniola, Cuba, and Puerto Rico relayed tales of a restorative river to the Spanish explorers they encountered. However, there is no valid evidence that there were Native myths of a fountain located anywhere within the Bahamas.

How did this rumor get started? Peter Martyr of Angleria, an Italian historian during the Age of Exploration, first published an account of the Fountain of Youth when writing of Juan de Solís, a 16th-century navigator. Martyr described "an island called by us Boinca, and by others Aganeo; it is celebrated for a spring whose waters restore youth to old men." Martyr wrote that this magical spring was located approximately in the Bay of Honduras, according to researcher Douglas T. Peck. Through a game of historical telephone, somehow the name Boinca became Bimini. Then came the apocryphal claims that Ponce de León was looking for a fabled land of Bimini.

So, what would appear as fact in sources as recent as the 1998 Encarta Encyclopedia was really just the work of 16th-century historians retroactively applying medieval legends to newly colonized regions.

The Fountain of Youth tourist attraction

Today, St. Augustine, Florida, has capitalized on its particularly mythic origin story. At the center of the city is a statue of a pointing Juan Ponce de León. Additionally, the town hosts the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park, which became a tourist attraction in the early 20th century. Here, tourists can sip from a sulfur-smelling spring, first documented in a 17th-century land grant, in the hopes of becoming rejuvenated, according to Legends of America.

In fact, as the location of Ponce de León's landing has been disputed, Florida boasts tens of locations purporting to be the Fountain of Youth, offering fountains of mineral water and soaks in thermal springs for visitors. As The New York Times reported, Punta Gorda, Warm Mineral Springs in the City of North Port, St. Petersburg, and more all claim to have revitalizing waters.

There is no evidence of any benefits from drinking these natural, eggy waters, but the St. Augustine tourist attraction is indeed a place of history. In 1934, the Smithsonian Institute undertook an archaeological dig in St. Augustine that uncovered a Spanish mission dating back to 1565, as well as Christianized Timucua burials from 1587.

Real lands of longevity

No magical, spice-scented waters flowing from Paradise with the power to restore youth have ever been found on Earth. Sorry, Prester John and Alexander the Great. However, while no lands of eternal youth actually exist, US researchers have identified five locations that have the highest concentration of centenarians in the world. As reported by NPR, Dan Buettner and anthropologists called these lands of longevity "Blue Zones." Buettner identified Ikaria, Greece, Okinawa, Japan, Ogliastra Region, Sardinia, Loma Linda, California, and Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica, as places where residents were most likely to live to 100.

They don't have rivers magically bestowing youth in these places. Researchers attributed the relative health and age of the populations to their moderate, plant-heavy diet, limited sugar and alcohol, active lifestyle, close-knit communities, and regular destressing practices. The data doesn't lie. In Okinawa, where the practice is to eat something from the land and sea daily, about 6.5 per 10,000 people live to be 100, compared to the 1.73 in 10,000 people in the United States. The Fountain of Youth might be a fable that has seduced explorers for centuries in search of their salad days, but the keys to longevity might have already been discovered.