Mysteries And Secrets Of The Shroud Of Turin

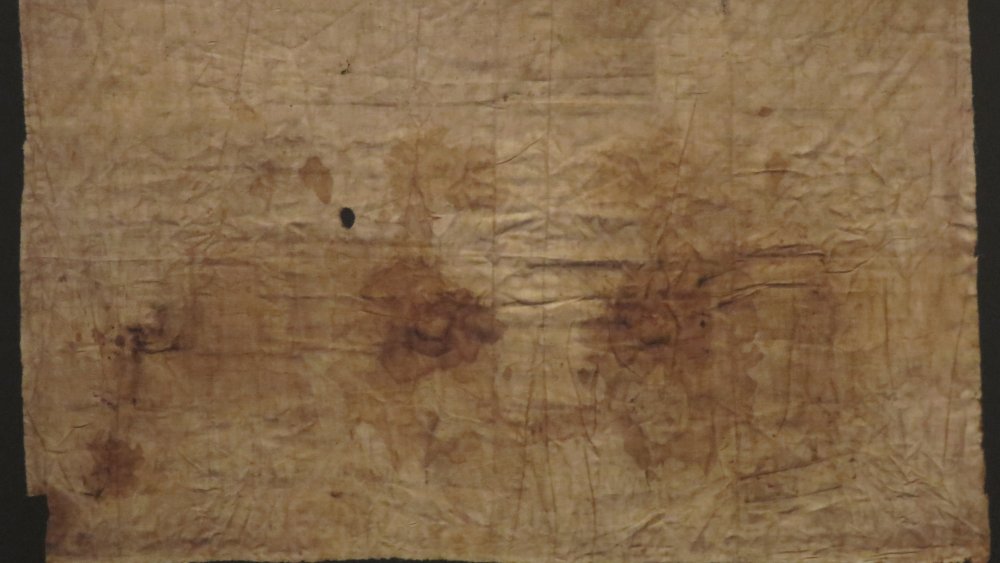

The Shroud of Turin is arguably the most famous Christian relic in the world. At about 14 feet long and three feet wide, this long strip of linen is said to be the very cloth in which Jesus (from the Bible) was buried in. More miraculously, this cloth bears the image of a nude, bloody, bearded man, front and back. Devotees of this relic claim that it shows the authentic Holy Face of Jesus, while skeptics claim that it's nothing but an impressive and puzzling forgery.

The Shroud of Turin is rarely made available to the public, so pilgrims hoping to get a peek will have better luck seeing the replica at the Museum of the Shroud in Turin, or — if you can't make the trip to Italy and want to go to Dollywood afterward – the one in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee. Alternatively, read on to discover the questions and mysteries that still hang over the Shroud today.

What the Bible says about Jesus' burial cloth

Believers in the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin say that it is the burial shroud of Jesus that has miraculously had a photonegative image of his face and body imprinted on it. The use of burial shrouds is, and has been for many years, a more or less universal practice in Jewish burial customs, so the idea that Jesus would have had one checks out. Plus, the Gospels all agree he had one — just maybe not 100-percent on the details.

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke – known as the Synoptic Gospels because they generally agree on a lot of stuff — all relate that after the crucifixion, Joseph of Arimathea took Jesus' body and wrapped it in a clean linen cloth before placing it in the tomb. That rebel John, however, says that Jesus was wrapped in strips of linen with spices, like a mummy. This description is repeated later when Peter finds the tomb empty except for the mummy wrap on the floor, plus a previously unmentioned separate head cloth. This distinction might seem minor, but the Shroud of Turin is definitely one single piece, over 14 feet long, enough to cover Jesus' front and back, vertically. Pretty hard to reconcile with the idea of strips and a separate head cloth, but maybe John whiffed this one.

The Shroud of Turin isn't the only magic Jesus face

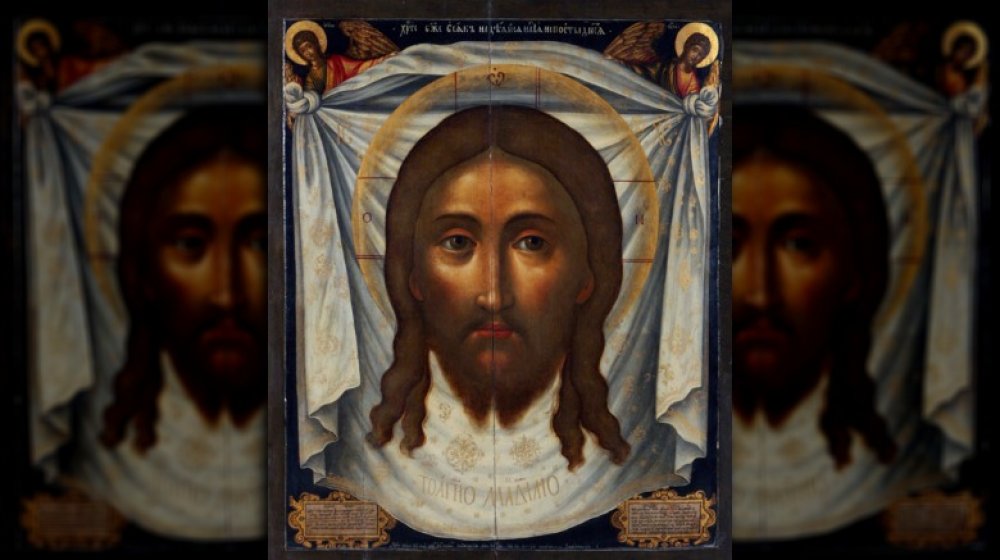

Although the Shroud of Turin might be the most famous relic that claims to bear the image of Jesus' face, it isn't the only one. In fact, there's an entire class of relics that is basically made up of objects in which Jesus' face was imprinted like newspaper ink on a wad of Silly Putty. These are called acheiropoieta, which is Greek for "made without hands."

Live Science reports on a couple of the more famous ones, including the Veil of Veronica. If you grew up Catholic, you might know that Veronica is the name of a woman who used her veil to wipe the sweat from Jesus' face as he was carrying the cross up to the site of his execution. When she did so, his face miraculously imprinted on the veil. If you weren't Catholic, you might not have heard this story, as it's not from the Bible but rather a medieval tradition. All copies of this veil were ordered destroyed by the pope in the 1600s, although St. Peter's Basilica allegedly has the original but doesn't display it to the public.

Other such pieces include the Mandylion (Greek for "towel"), a cloth on which Jesus dried his face to heal a king of leprosy, and the Camuliana Christ, a linen cloth with Jesus' face on it found floating on a river when a pagan woman demanded visible proof of Christ.

The early history of the Shroud of Turin

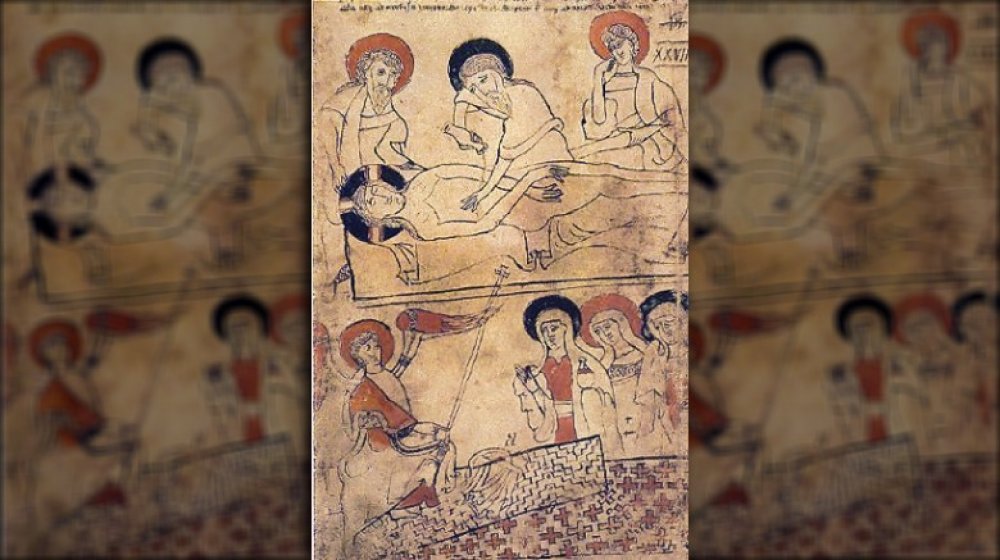

Like a lot of historical mysteries, it can be hard to nail down exactly what the first definite mention of the Shroud of Turin is, as there are a number of oblique references to similar objects that might be this particular relic but also might not. A key example, which, if it is a reference to the Shroud, would be the earliest one found so far, is an image from a Hungarian manuscript known as the Pray Codex. That's right, it's not even a textual mention — it's a drawing that maybe depicts the Shroud. However, while it's notable that this image includes a rectangle that might indicate a burial shroud for Jesus, you should also notice that this rectangle is definitely not imprinted with the image of Christ but rather some crosses and a kind of zigzag pattern. Is it a shroud? Is it a tombstone? Is it just a decorative motif? Who can say?

Another early maybe comes from the 1300s in France. As Encyclopedia Britannica explains, by 1354, the famous knight Geoffroi de Charnay, known for his accomplishments in the Hundred Years' War, possessed a shroud that seemed to bear the image of a man who had been crucified and was displaying this sheet in his tiny French town of Lirey. It is possible that he came into possession of this relic during a disastrously failed crusade in Smyrna in the 1340s.

The first person to talk about the Shroud called it a fake

The earliest sure-for-sure mention of the Shroud of Turin comes a few decades after the death of Geoffroi de Charnay, the knight who allegedly owned it. Somewhat ironically, the first reference that is clearly specifically to the relic we know today as the Shroud of Turin is a denunciation from a local bishop telling the pope that it is definitely a forgery. According to The New York Times, in 1389, Pierre d'Arcis, bishop of Troyes, sent a report to Pope Clement VII that he had seen an exhibition of the shroud (probably the one belonging to Geoffroi some 35 years earlier) and that it was not only fake, but when confronted, the guy who had made it confessed to having painted it.

In the bishop's own words, this was "a certain cloth cunningly painted, upon which by a clever sleight of hand was depicted the twofold image of one man, that is to say, the back and the front, he falsely declaring and pretending that this was the actual shroud in which our Savior Jesus Christ was enfolded in the tomb." This cloth was exhibited as authentic and had "pretended miracles" attributed to it, but it was forged "not from any motive of devotion but only of gain." Despite this strong and unambiguous report, Clement did not officially denounce the Shroud, so its authenticity has been debated for over 600 years.

Miracles of the Shroud of Turin

The very existence of the Shroud of Turin itself is believed to be a miracle, but any good relic worth its salt is responsible for a number of miracles performed upon people in its proximity. Naturally, a relic of the resurrection, literally the most important moment in the history of Christianity, has some magical achievements on its résumé.

Works by Faith Ministries records a few such miraculous events, including a few normally attributed to the Mandylion (some Shroud fans believe that the Mandylion was just the Shroud folded up), such as defending the city of Edessa from invasion by the Persian army and healing its king of leprosy. The Shroud is believed to have made its way to the Byzantine emperors in Constantinople, and a man who touched the Shroud while it was processing there was healed of demonic possession.

A more modern miracle occurred in 1954, when an 11-year-old girl from England who was dying of a bone disease and lung abscesses learned about the Shroud and asked to see it. Doctors had said the girl had no hope, and she had already been given last rites, but even holding a photo of the Shroud led to a partial remission of her disease. After receiving special permission from the Shroud's then-owner, the king of Portugal, she was able to see and even touch the Shroud. And, or so they say, she was fully healed.

How did the Shroud of Turin's famous image get made?

The largest question surrounding the Shroud of Turin, besides, of course, its authenticity, is how the image was made. How did a photonegative image of a human man get impressed on a piece of cloth sometime in the 14th century at the latest? There are, naturally, many different theories, and the BBC records a number of them. Believers in the authenticity of the Shroud claim that the image came from a release of radiant energy at the moment of the resurrection. Some such believers try to science up this claim with words like "electrostatic discharges," but the short version is still that it's a miracle. Which, you know, maybe it is.

Non-miraculous explanations include that it's a painting, like the bishop of Troyes claimed, but there are no identifiable pigments or brushstrokes in the image. The fibers don't seem to be painted but rather fully darkened, leading to the theory that the residual image could have been caused by a natural chemical process related to heat from the decomposition of the body wrapped in the Shroud. However, the fact that the image is a photonegative has raised the possibility that it is some kind of primitive photograph, involving the cloth having been coated in silver nitrate, a light-sensitive compound used later in legitimate photography. None of these theories, however, are completely satisfactory.

Dating the Shroud of Turin

The primary approach to trying to confirm or disprove the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin has been to attempt to scientifically determine its age. After all, if scientists can definitively prove that the Shroud is no older than, for example, the 14th-century date in which it first appeared, then we can pretty much write off the idea that it's an artifact from first-century Judea. As Encyclopedia Britannica explains, scientific endeavors to determine the chemical makeup and processes used in the creation of the Shroud's image have been going on since the 1800s, but it wasn't until 1988 that the Vatican provided labs with samples of the Shroud in order to perform carbon-14 tests to narrow down the age of the cloth. All three labs independently determined, with 95-percent confidence, that the cloth dated somewhere between 1260 and 1390, placing it square in the period in which the bishop of Troyes was calling it a hoax.

The Independent reports that some scientists have taken a different tack in questioning the authenticity of the relic: namely that forensic investigators have examined blood spatter patterns on the Shroud to determine that the bloodstains on the cloth could only have been made by someone adopting various different poses rather than lying still as a (temporarily) dead person presumably would.

What if the dating was wrong?

Perhaps not surprisingly, many Shroud of Turin supporters have not been persuaded by the results of the 1988 carbon-dating which concluded that the Shroud was a medieval creation. There have been a number of different claims by groups suggesting that the carbon tests were tainted, corrupted, or otherwise flawed. As Chemistry World explains, there are some scientific fringe groups who contend that the results of the test were inconclusive due to elements such as the presence of fungi on the cloth, areas affected by fire damage, or the idea that the small samples provided to the labs were not, in fact, representative of the material of the Shroud as a whole.

The Telegraph reports that many people who reject the results of the carbon-dating are following the lead of a researcher from the Shroud of Turin Research Project (also known as STURP) who, before his death, said he had reversed his conclusion on the results of the Shroud test and believed that the cloth was authentic. His argument was that the areas sampled came not from the original Shroud but rather from patches made to repair the relic after it had suffered fire damage. Chemistry World, while skeptical of this claim, agrees that it is time for another round of scientific study on the Shroud using state-of-the-art techniques, but that's ultimately up to the Vatican.

Does the Shroud of Turin have Jesus' name on it?

While the Shroud of Turin is most famous for its ghostly image depicting the body of a crucified man, one researcher claims that there's more to be seen imprinted on the cloth. According to the Associated Press, a Vatican archives researcher named Barbara Frale used computer-enhanced images to examine the Shroud and found evidence of faint text in Greek, Latin, and Aramaic written on the surface of the cloth. Within this text, she claims to have recognized at least 11 different words, including the name "Jesus of Nazareth." Her hypothesis is that the text is from ink that rubbed off onto the cloth and was originally from a kind of death certificate for Jesus glued to the Shroud by the Romans.

Interestingly, she claims that the strongest evidence for authenticity of the text is not what's there but rather what isn't: There is no suggestion of the divinity of Jesus within the words she found, something she is confident that any medieval forger would definitely have included. It is important to note, however, that many experts have expressed skepticism around Frale's findings and say that there are not, in fact, letters to be found among the grainy images that she examined and that her mind was seeing what she wanted to see rather than what was actually there. The "letters" are actually patterns created by the increased contrast of the enhanced photos, bolstered by a hopeful imagination.

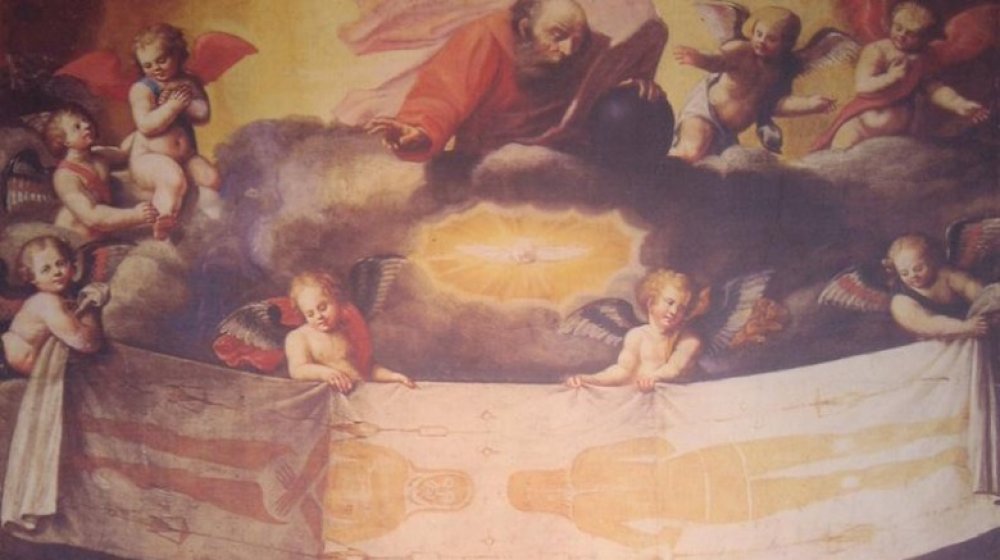

The Shroud of Turin survives fire, twice

In 1453, Margaret de Charny inherited the Shroud of Turin from her grandfather, Geoffroi de Charny, the knight who was exhibiting the relic in France in the 1300s, after he died in the Hundred Years' War. As History explains, Margaret went on to trade the Shroud to the House of Savoy — a royal house that ruled over land in what is now France, Switzerland, and Italy — for two castles, an act for which she was excommunicated. In 1502, the Savoys placed the Shroud in a chapel in Chambery, now part of France.

Thirty years later, a fire broke out in the chapel, melting the silver container in which the Shroud was kept, dripping molten silver onto the cloth and scorching it. Those burn marks and the water stains from the fire being extinguished are still visible on the Shroud today. Afterward, the Savoys moved the Shroud to the chapel of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, where it's been basically ever since, which is why it's the Shroud of Turin and not the Shroud of Lirey or Chambery.

This move didn't fully protect the Shroud from fire, however. As The Spokesman-Review reports, the Turin chapel was devastated by a five-hour fire in 1997 that did millions of dollars' worth of damage. Thankfully for the Shroud, its silver urn was quickly rescued from the flames by firefighters, who had to hammer through four layers of bulletproof glass.

Other burial shrouds of Jesus

You might be forgiven for thinking that the Shroud of Turin is the only claimant to being the authentic burial shroud of Jesus. It is, after all, the most famous one, and how could it have as much popular support as it does if there were other cloths claiming to be the real thing? If, however, you know anything about relics, you'd actually be more surprised if there weren't other shrouds out there.

Turin's main "competitor" comes in the form of the Sudarium ("sweat cloth") of Oviedo, a bloodstained cloth that is alleged to be the head wrapping placed on Jesus' body in the Gospel of John. According to Shroud.com, this cloth was taken from Palestine in the seventh century and eventually made its way to Spain, and it has been in a special box in a chapel in Oviedo since 840 C.E. Some people claim, however, that rather than being a competing shroud, the Sudarium and the Turin shroud are part of a matching set.

Other relics in France and Italy also claim to be either the shroud or various pieces of Jesus' multipart funereal ensemble. A notable example is the Sainte Coiffe ("holy headdress," said to have been tied around Jesus' chin to secure his jaw), eight layers of bloody gauze found in the Cahors Cathedral in France, which was displayed for pilgrims in 2019 to celebrate the cathedral's 900th anniversary.

The Vatican's ambiguous stance on the Shroud of Turin

Despite the fact that the Shroud of Turin is arguably the most famous relic in the Christian world, the Catholic Church has maintained a somewhat ambiguous stance on its authenticity. This could very well be because the first time a pope heard about the Shroud was someone telling him that it was definitely a money-grubbing forgery, but who can say?

As Britannica points out, the Vatican has no official stance on the authenticity of the Shroud, and, in fact, refers to it as an icon rather than a relic, being careful only to state that it is an image of Christ and not necessarily a thing made by his magic body radiation. This is not super surprising, as the Church does not usually take official stances on the authenticity of such relics. Nevertheless, as an object, the Church promotes the Shroud as being worthy of veneration as an "inspiring image of Christ."

However, since 1940, the Church has approved the production of medals bearing the face from the Shroud on it, known as the Holy Face Medal, and the Vatican has owned the Shroud since 1983, when it was given to them by the House of Savoy. In 1998, Pope John Paul II called the Shroud "a mirror of the Gospel," and Pope Francis made a pilgrimage to see it in 2015, both of which kiiiiiiinda feel like endorsements.