The Untold Truth Of Alexander The Great

Despite being one of the most famous rulers in all of history, the life of Alexander the Great isn't as easy to pin down as you might think. Many of the stories and histories about the Macedonian ruler were recorded after the fact by historians like Plutarch who were known to stretch the truth once in a while. Much of what we know about Alexander's life is largely speculation from such stories, and they continue to be debated by scholars. But like with all good interpretations, everything depends on what evidence there is and the quality of that evidence.

As with all people, Alexander was a complex character whose actions and motivations can forever be debated. But amidst all the musky legends, one thing is for certain — the fact that we continue to discuss him means that he reached the god-like immortality that he professed to have his entire life.

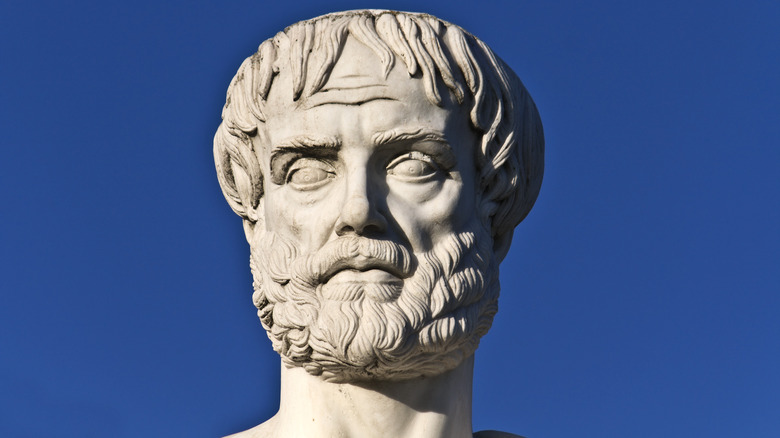

Ruling through Aristotelian philosophy

When Alexander the Great was a young teenager, his father King Philip II of Macedon hired the philosopher Aristotle to tutor him. Although they only spent a few years together, some writers and historians like Plutarch claim that Alexander and Aristotle maintained contact even after Alexander had set off on his campaigns. The University of the Aegean, Rhodes writes that when Alexander learned that Aristotle had published his writings and philosophy, he was dismayed that his tutor was sharing his wisdom with others. Plutarch claims that Alexander wrote to Aristotle with his complaints, but there is debate over whether or not this account is factual.

Even though Aristotle only tutored Alexander for three years and likely had sparse contact with him afterward, some scholars believe that the philosopher's lessons and teachings had a lifelong effect on the king and how he ruled. According to Apeiron Centre, Aristotle underlined the significance of the city in his philosophy, stating that "the city is prior by nature, to the household and each of us." And the fact that Alexander continuously founded cities, many with his own name but also others of varying names, can be understood as an attempt to bring to life the idea of the Aristotelian city.

The fact that Alexander didn't impose his culture during his conquering is also attributed to the lessons he gained from Aristotle — in this case by following Aristotelian teaching methods.

Demigod or Oedipus complex?

Alexander the Great didn't wait for others to mythologize him — he intended to exist in the world of the gods from the very beginning. Alexander did so by claiming divine relations, saying he was a relative of both Achilles and Heracles as well as a son of Zeus to establish himself as a demigod. The idea that Alexander was in fact a demigod was especially fuelled by the fact that after he died, his body seemingly didn't start to decay for almost a week. According to the World History Encyclopedia, the idea that Alexander's father was actually Zeus was an idea implanted by his mother, who claimed that she had given a virgin birth to him after lying with a serpent.

However, some psychoanalysts argue that Alexander the Great's self-confidence and hero mythologizing are because he had an unresolved Oedipus complex with his mother Olympias. While it's difficult to posthumously describe someone's personality, especially after thousands of years, psychoanalysts base this theory on accounts of Alexander's sadistic and narcissistic behavior as well as his near-constant desire to please his mother. A piece in The Psychoanalytic Review writes that Alexander held a great deal of love for his mother and was loyal to her throughout his life, even against his own father. Olympias was also influential throughout his life and in many of his campaigns, evidenced by the fact that he often wrote to her for advice.

An expensive funeral for a boy toy

Even though the term bisexuality didn't really exist in Alexander the Great's time, accounts of his life have led scholars to describe him as bisexual — largely due to his relationship with Hephaestion, his personal bodyguard. A close friend of his from childhood, their connection is thought to have been more than just platonic. But this was well within the norm in Alexander's time, which included homosexual relationships between men of both the same and varying ages.

Alexander is reported as having several heterosexual lovers, including his multiple wives. But historians believe his relationship with Hephaestion was one of the most important relationships of his life. And in line with his own mythologizing, Alexander compared his relationship with Hephaestion to Achilles' relationship with Patroclus, which was also rumored to be homosexual. Alexander went so far as to honor their bond by placing a wreath on the tomb of Achilles while Hephaestion lay a wreath on the tomb of Patroclus.

When Hephaestion died, Alexander went into an intense mourning and reportedly cried for two days straight. According to "Homosexuality and Civilization" by Louis Crompton, he went on to cut his hair and killed the doctor who'd been unable to save Hephaestion. Hephaestion was subsequently cremated, and Alexander threw such a large and lavish funeral that it reportedly cost 10,000 talents, equivalent to over $3 billion.

Walking on water

When Alexander the Great wanted to conquer, no element could stand in his way. That's how he ended up walking on water in 332 B.C. during his siege on Tyre, Phoenicia, now modern-day Lebanon. Although Alexander claimed to want to enter Tyre in order to make a sacrifice to Heracles, his ruse was recognized and rejected, leading him to attack the city.

But the fact that Tyre is an island more than half a mile away from the shoreline meant that Alexander had to contend with an extremely well-fortified city while trying to attack from the sea. In response, he came up with the idea of buying a causeway that would allow his soldiers to reach the city on foot. This allowed Alexander to attack Tyre from both sides with soldiers on foot and soldiers on ships. Overall, the siege took seven months, and when Alexander finally conquered the city, he razed it to the ground. Over 8,000 Tyrian people were killed while another 30,000 were sold into enslavement, writes World History Encyclopedia.

Building the causeway is no easy feat, and archeologists have puzzled over how it was created for centuries. According to Live Science, it was only in 2007 that archaeologists discovered a naturally occurring sandbar in the water that Alexander likely used. And this wouldn't be the last time that Alexander walked on water, as he later built a causeway to link Alexandria to the mainland as well.

A drunken rampage?

After Alexander the Great conquered the city of Persepolis — the capital of the Achaemenid Empire in what is now considered Iran — he burned the city down in a spectacular display. But despite this famous event going down in history, scholars aren't sure exactly why the king decided to burn the city down. Some scholars even argue that Alexander himself didn't know why he did it.

According to ThoughtCo., Alexander is believed to have burned Persepolis due to revenge, political gains, or simply a drunken rage. He claimed that he was destroying Persepolis because the Persians had destroyed the Acropolis in Athens. But the morning after he burned Persepolis, World History Encyclopedia writes that Alexander was incredibly regretful of this decision. Had the burning of the city been a political move, it's unlikely that Alexander would've immediately regretted his decision.

The fact that Alexander was so regretful suggests he didn't decide to burn the city of Persepolis with a sober mind. And while his motivations are unclear, historical accounts of the decision all maintain that he was drunk when he decided to burn down the city. But even the reason for Alexander's regret is unclear, for no one knows if he remorseful for destroying priceless works of early Zoroastrianism and ruining a potential pillaging opportunity.

Did Alexander murder his father?

Alexander the Great's father, Philip II of Macedon, was a successful king in his own right and had his own dreams of conquering Persia. But despite Alexander following in his father's footsteps and achieving his dreams, the two didn't always get along. Historians believe that Alexander resented the fact that his father was seeking a successor to the throne more legitimate than him. During Philip's wedding to Cleopatra Eurydice in 337 B.C., after Macedonian commander Attalus prayed out loud for a legitimate heir, Alexander reportedly exclaimed, "Why, traitor, what am I? Dost thou take me for a bastard?" According to the McGill Journal of Classical Studies, his father almost physically attacked him afterward.

But were their family disputes so great that Alexander would go so far as to have his father murdered? Although historians don't dispute the fact that Philip was killed by Pausanias as an act of revenge (possibly related to a sexual assault), Alexander and his mother Olympias are incriminated as part of a larger ploy in some historical retellings. Even Plutarch notes that suspicion was cast over Alexander. And the death of Philip was especially handy for Alexander, who promptly succeeded his father and became King of Macedonia. But as historian Adrian Goldsworthy notes, there's not enough information about Alexander's personality or motivations to say for sure whether he was responsible.

Employing eunuchs

After conquering Persia, Alexander the Great adopted several of its customs, including integrating Persian clothing style into his Macedonian royal clothes and using a Persian-style tent. In addition, he added Persian people to his court and specifically adopted the practice of employing royal eunuchs.

Macedonian soldiers were not necessarily comfortable with Alexander's adoption of Persian customs. But Alexander didn't care about whether or not his actions were approved of, especially when it came to the eunuchs he engaged with. One eunuch in particular, a man known only by the name Bagoas, was a known sexual partner of Alexander that the king allegedly publicly kissed during a festival. Originally given to Alexander as a gift by a Persian nobleman, Bagaos became such an influential part of Alexander's court that some historians attribute to him the fact that Alexander adopted so many Persian customs.

And it is notable that Alexander didn't just accept Bagoas but actively integrated him into his life and royal court. This was not something that was normalized in Alexander's culture — Eunuchs were not usually a part of Macedonian court. And according to the "Routledge Companion to the Reception of Ancient Greek and Roman Gender and Sexuality," edited by K. R. Moore, it was likely due to Alexander's adoption of royal eunuchs that they continued to be used by his successors and ultimately became a part of Hellenistic kingdoms.

The Great or the Accursed?

Although Alexander the Great is given the epithet "the great," not everyone thought of him as such, especially those that he conquered. This is clear by the fact that other cultures — like Persian — instead refer to Alexander as Alexander the Accursed. Another moniker used for the king in Persian literature is the "two-horned Satan," according to The Hudson Review. Additionally, The Collector writes that Persian works about Alexander often associate him with demonic and apocalyptic imagery.

The use of satanic and demonic imagery to refer to Alexander in Persian literature comes out of the fact that he was a brutal conquerer who spared no expense when it came to bloodshed. On more than one occasion, he slaughtered thousands of people for refusing to cooperate with him. HistoryNet writes that despite all the fanfare about Alexander's military conquests, he can just as accurately be described as a murderous monster who was willing to kill anyone who got in his way, even children. Even when civilians surrendered, Alexander was known to massacre them as punishment for their resistance.

And even though Alexander adopted Persian customs into his life and court, he showed little respect for their culture while he was actually in Persia. During his conquests, Alexander destroyed many Zoroastrian temples, and this destruction resulted in the loss of countless cultural and religious artifacts and literature — especially with the burning of Persepolis.

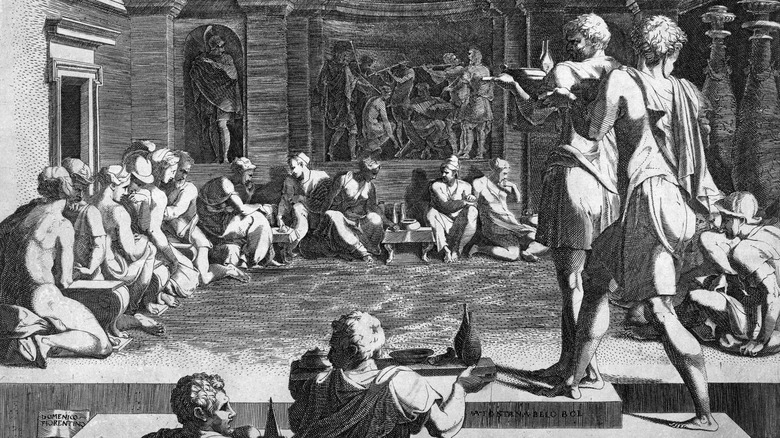

No thanks for saving his life

Overall, Alexander the Great had little tolerance for anyone who criticized him, much less outright defied him. This was true of anyone, even those who were responsible for saving his life.

During the Battle of Granicus in 334 B.C., Alexander would have died at the hand of a Persian cavalryman were it not for Cleitus the Black, a Macedonian general in Alexander's army. According to "The Madness of Alexander the Great" by Richard A. Gabriel, Cleitus cut off the soldier's arm before he could kill the king. But the thanks from Alexander didn't last very long. Less than 10 years later, in 328, Alexander stabbed and killed Cleitus with a pike during a symposium for criticizing him and making fun of his claims of divinity. Considering that Alexander was heavily drunk at the time, this murder is just another in his long line of drunken rampages. Once he sobered up, he was instantly regretful of murdering Cleitus.

The following year, Alexander went on to kill someone else close to him who criticized him — his personal historian Callisthenes of Olynthus. In a tragic juxtaposition, Kenneth Royce Moore writes in "Framing the Debate" that Callisthenes was one of the people who comforted Alexander when he felt bad about killing Cleitus. But ultimately, no matter the relationship that Alexander had with someone, if he felt that they were being disrespectful or treasonous in any way, he wouldn't hesitate to end their life.

Who doesn't want more wives?

In 324 B.C., Alexander the Great organized a mass wedding known as the Susa weddings. According to "Environment, Social Justice, and the Media in the Age of the Anthropocene," the event intended to promote integration with Persian culture. As a result, Alexander made 10,000 of his soldiers get married to a Persian woman.

And Alexander himself was not exempt from this. At the time, he was already married to Roxane, a Bactrian woman, and during the Susa weddings he married Stateira, the daughter of the Persian King Darius III, making her his second wife. But apparently, that wasn't enough integration for Alexander, for he ended up taking another wife during the Susa weddings: Parysatis. According to "Women and Monarchy in Macedonia" by Elizabeth Donnelly Carney, Alexander did this because he wanted to make sure that he married into all existing branches of the royal family. In one fell swoop, the king went from having just one wife to having three.

In line with his adoption of Persian customs, Alexander also celebrated the weddings in accordance with Persian customs and traditions, Pierre Briant writes in "From Cyrus to Alexander."

A city for his horse

The death of Hephaestion wasn't the only incident that caused Alexander the Great to go into a period of deep mourning. The death of his favorite horse, Bucephalus, also shattered his heart. Alexander received Bucephalus from his father Philip II when he was only 10 years old, but the animal wasn't originally intended for him. The famous story goes that Philip was initially given Bucephalus, but the horse refused to let anyone near him, and Philip ordered it to be taken away. But Alexander, realizing that the horse was not afraid of people but of its own shadow, managed to turn it around and ride off on it.

Alexander and Bucephalus rode together into every battle for almost 20 full years until Bucephalus finally died. And according to Plutarch, Alexander was "plunged into grief" as a result. After the death of Bucephalus, the ruler decided to honor his horse the way that he constantly honored himself — by founding a city, Bucephala, in Bucephalus' name. And this wouldn't be the only time that Alexander honored an animal companion of his — Plutarch writes that Alexander also named a city "Peritas" when his favorite dog by the same name died. However, Plutarch is the only one to make the claim about Alexander's dog, while the story of Bucephala is more widely recollected by historians.

One last drunken rager

Alexander the Great was known for being an incredibly heavy drinker, and he lived up to this image up through to his last day. Before his death, sometime around the beginning of summer in 323 B.C., he reportedly went on a drinking binge for several days with fleet admiral Nearcus and his friend Medius of Larissa. However, Literary Hub notes that at the start of their drinking binge it was clear that something was off because Alexander reportedly left the party early to go to bed — something that he had never been known to do.

Although the drunken revelries were fun and games for a while, on one particular evening, Alexander felt a sharp pain in his back. Di Che Cibo 6? Magazine writes that during this time, he had already drank over 5 liters of undiluted wine. Although he took a pause when he felt the pain in his back, it wasn't long before he continued drinking, and his fever kept worsening. He reportedly kept feeling thirstier and thirstier, but as he continued to drink the wine, it wouldn't quench his thirst. Unfortunately, although the drinking may have dulled the pain, it couldn't stop his worsening condition, and he never recovered after the fever.

How did Alexander die?

Despite Alexander the Great's historical legacy, his death remains somewhat of a mystery. Historians still aren't sure exactly how he died and whether it was an illness or an assassination. From the moment the ruler passed, people started coming up with theories and haven't stopped for over 2,000 years.

Some historians believe that Alexander may have died from malaria or meningitis while others blame contaminated water. And although some initially believed that Alexander could have died from natural causes, others started to suspect that his death was in fact an assassination. Some researchers have even used anecdotal tales about Alexander to make a diagnosis. According to Emerging Infectious Diseases, Plutarch mentions a story about ravens dying at Alexander's feet when he entered Babylon. This might suggest an epidemic of West Nile virus in the region, which could have resulted in Alexander's symptoms and death. But unfortunately, just like the stories of the king's life, it's difficult to distinguish fact from fiction when it comes to his death.