The Crazy True Story Of The Hollywood Blacklist

The Hollywood blacklist refers to a dark time period in not only in the entertainment industry but in United States history. In 1938, anti-Communist sentiment gave rise to a committee within the House of Representatives, the House Un-American Activities Committee, or HUAC. The committee soon focused almost exclusively on investigating American citizens, usually employed within the Hollywood film industry, on the basis of their alleged or actual membership in, sympathy to, or association with the Communist Party or their refusal to cooperate with Congress' investigations.

HUAC's secretive, fearmongering methods, encouragement of people to turn against one another in order to deflect persecution, abuse of its ability to subpoena citizens at will, and its tactic of implying that those who pleaded the Fifth Amendment during questioning did so because they were guilty of their supposed crimes amount to perhaps one of the only legitimate historical situations that could be accurately described as a metaphorical "witch hunt." In fact, Arthur Miller was inspired by his experiences with HUAC to write his play The Crucible, using the Salem witch trials as an allegory for both HUAC's investigations as well as those of Senator Joseph McCarthy.

The formation of the House Un-American Activities Committee

According to Teaching Eleanor Roosevelt, the United States House of Representatives established the House Committee on Un-American Activities (a.k.a. the House Un-American Activities Committee, or HUAC) in 1938 as a special investigating committee to examine "alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having Communist ties." Martin Dies Jr. (pictured above), a right-wing Democratic representative from Texas, chaired the committee, which almost immediately became notorious for using its power to issue subpoenas and hold witnesses in contempt of Congress, as well as for popularizing the act of red-baiting, or "the act of attacking or persecuting as a Communist or as communistic."

As the Committee began its investigations, they "exposed activities of Italian Fascist consuls and the anti‐Semitic Silver Shirts," but their efforts "mushroomed into inquiries into alleged Communism in hundreds of organizations, Government agencies and the Michigan sit‐down strikes," as reported in Dies' New York Times obituary. President Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke out against HUAC from its beginnings, criticizing its tactics as "flagrantly unfair and unAmerican." HUAC was supposedly intended to investigate Fascism in the United States as well as Communism, but Dies was primarily concerned with what he convinced was a Communist threat to the American way of life, as indicated in his 1940 book The Trojan Horse in America.

Theater was attacked first

A 1941 review of The Trojan Horse in America in Foreign Affairs magazine called the book "further indication that Mr. Dies is rather more interested in promoting himself and his anti-New Deal and anti-"Communist" activities than in going after the Nazi and Fascist Fifth Columns, whether homegrown or imported." Indeed, Martin Dies was particularly focused on investigating aspects of Roosevelt's New Deal that he found troubling, including the Works Project Administration. The Federal Theatre Project, a division of the WPA, was headed by experimental theater scholar and producer Hallie Flanagan (pictured above). In 1938, HUAC member J. Parnell Thomas described the Federal Theatre Project as, according to Spartacus Educational, "infested by radicals from top to bottom." Other WPA employees described Flanagan as sympathetic to Communism and pointed to her interest in Russian theater and the project's productions of socially progressive plays as proof.

Flanagan described the hearings as reminiscent of "a badly staged courtroom scene" as opposed to "a congressional hearing on which the future of several thousand human beings depended." Thomas referred to her productions as "sheer propaganda for Communism or the New Deal," and Dies soon called for the resignation of several members of Roosevelt's administration because of their associations with "Socialists, Communists, and crackpots." Roosevelt didn't fire any of his associates, but he did end the Federal Theatre Project four years after it began, which one can assume bolstered and encouraged HUAC in its attempts to persecute creative professionals.

Shirley Temple: Communist sympathizer?

One of HUAC's first attempts to connect Hollywood with Communism also came in 1938 when, according to The Federalist, they released the testimony of Dr. J.B. Matthews, a disillusioned former activist who had worked directly with the Communist Party USA but went on to be one of the first to offer up anti-Communist testimony to the committee. Matthews discussed his fear regarding the "carelessness or indifference of thousands of prominent citizens in lending their names for [the Communism Party's] propaganda purposes" and reported that "the French newspaper Ce Soir, which is owned outright by the Communist Party, featured hearty greetings from Clark Gable, Robert Taylor, James Cagney, and even Shirley Temple. [...] No one, I hope, is going to claim that any one of these persons in particular is a Communist."

HUAC read Matthews' testimony on an NBC broadcast, making them a part of the general political discourse. Roosevelt's government, fighting back against HUAC's attacks upon their New Deal policies, seized upon these remarks and used them to point out the absurdity of HUAC's agenda. Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes was particularly cutting: "They've gone into Hollywood and there discovered a great Red plot. They have found dangerous radicals there, led by little Shirley Temple. Imagine the great committee raiding her nursery and seizing her dolls as evidence." To this day, people misquote Ickes and report that HUAC literally accused Shirley Temple of being a Communist, but their tactics were a bit more insidious and subtle.

HUAC's Hollywood: A hotbed of Communism

As explained by Larry Ceplair in a 2008 Film History article, in 1940, Dies turned his attention to Hollywood. He called the film industry a "hotbed of Communism," compiled a long list of "subversives," and wrote two articles for Liberty magazine: "The Reds in Hollywood" and "Is Communism Invading the Movies?" Nevertheless, he received no support from studio heads at that point, and actors, writers, and directors remained united in their opposition to HUAC and their harassment. Despite this, Dies carried on and heard testimony from former Communist organizer John L. Leech, who named 43 people, including Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney, as "members of, contributors to, or interested in the Communist party." Dies released the list of names and offered to "clear" those who agreed to testify, later doing so for all but one of those named.

In 1941, Walt Disney took out an ad in Variety concerning a workers' strike at his studio. Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund quote it in their 1980 book The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960: "I am positively convinced that Communistic agitation, leadership, and activities has brought about this strike." Disney's mistreatment of those who worked for him reportedly led to the strike, but Disney's anti-Communist screeds were just beginning. He testified for HUAC and named as possible Communists employees who had been particularly active in his company's attempt to unionize. The committee eventually cleared all those he accused.

The Hollywood Ten

In July 1946, at the height of post-World War II anti-Communist sentiment in the United States, William R. Wilkinson of The Hollywood Reporter published a column called "A Vote for Joseph Stalin," in which he named 11 people as Communist sympathizers. In the following months, Wilkinson went on to name more people in more columns. HUAC used Wilkinson's lists to subpoena 43 people. Nineteen of those declared they would not give evidence, citing the First Amendment, while 11 were called before HUAC, per Britannica. One, playwright Bertolt Brecht, answered the committee's questions and then left the United States. The other ten, screenwriters Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ormitz, and Dalton Trumbo, screenwriter and director Herbert Bibermen, director Edward Dmytryk, and producer and screenwriter Adrian Scott, continued to refuse and became known as the Hollywood Ten.

The House of Representatives voted to charge the Hollywood Ten with contempt of Congress, and the Motion Picture Association of America released a statement, read by MPAA president Eric Johnston and signed by 48 movie executives, announcing that the ten were suspended without pay, the five currently under contract would be immediately fired, and none would be reinstated until their contempt charges were cleared and they swore they were not, and had never been, Communists or sympathetic to Communism. This ended the tacit support studios had until then given to those targeted by HUAC and signaled the beginning of their cooperation with the committee's harassment and intimidation.

Controversial and unable to work

According to Ceplair and Englund, the Hollywood Ten went to great lengths to gather support for their case as well as for freedom of speech, raising funds, embarking on speaking tours, and organizing an anti-censorship campaign. Their case eventually reached the Supreme Court after a series of appeals and was denied review, which meant that the Ten had no choice but to begin serving jail sentences of one year. One of those convicted, Edward Dmytryk (pictured), later publicly announced that he had been a Communist at one time and offered to give evidence against others, stating that "the people who had broken with the Party had to be helped, both because it was the right thing to do and because it hurt the Communist Party." He named 26 people to HUAC, and as a result, his sentence was shortened and his career rebounded.

In his 1999 paper "How the Film and Televsion Blacklists Worked," Richard A. Schwartz described how the American Legion pressured studio heads to enlarge the blacklist. In 1951, they provided a list of 300 "subversives." Additionally, three former FBI agents who called themselves American Business Consultants, Inc. started a newsletter called Counterattack with the aim to "crush the Communist Fifth Column." Counterattack published a booklet in 1950 called Red Channels that listed 151 supposed Communist sympathizers and included "proof" of their Communist involvement. A listing in Red Channels made a person "controversial" and therefore ineligible for employment in Hollywood.

Scorned agents of a foreign government

Over 250 writers, directors, and actors ended up being blacklisted. Reasons for blacklisting included merely speaking out against the practice: In his 2004 book Perilous times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism, Geoffrey R. Stone describes how 204 members of the Hollywood community signed an amicus brief supporting the Hollywood Ten, and 84 of those were then blacklisted themselves. Several people who had intended to defend the accused ended up instead naming names to HUAC to avoid becoming one of the accused and losing their livelihoods.

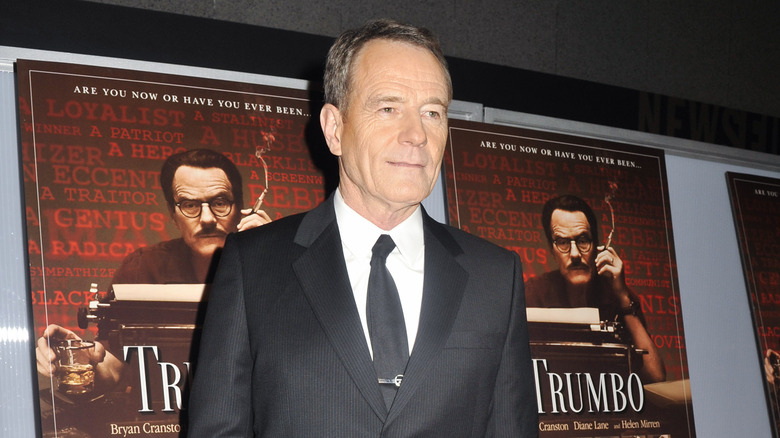

The remaining nine of the Hollywood Ten were all out of jail by May 1951 but weren't able to go back to work because no one would hire them. Ceplair and Englund point out that though the nine men were out of prison, they were not actually free, as they weren't "free to pursue their careers, to continue their political activity, or to be anything other than scorned 'agents of a foreign government.'" Some of the Ten, including Dalton Trumbo, Ring Lardner Jr., and Albert Matz, moved to Mexico and formed a community. As detailed by The Hollywood Reporter, Trumbo continued writing for the screen, using "fronts" named as the authors of his works or pseudonyms. Two of his screenplays from this period, 1953's Roman Holiday and 1956's The Brave One, won Academy Awards for best screenplay. Trumbo's life was dramatized in the 2015 film Trumbo, starring Bryan Cranston.

Graylisted: worse than the blacklist?

As described by Ceplair and Englund, as the investigations continued, more organizations in addition to Counterattack formed, feeding information to HUAC and employing "smear and clear" tactics in which they attacked political activists and then "offered their services" to cleanse the dirty accusations they themselves had brought, which required naming names of fellow members of the entertainment industry who could then be persecuted. These organizations included the Wage Earners Committee, who made their own lists of subversive people and media and led pickets of "dangerous" movies, and Aware, Inc., a group of New York actors who named and blamed supposed Communists via their publication Confidential Notebook.

In addition to the official blacklist, which listed those called by HUAC who refused to cooperate and those who were identified as Communists during hearings, there was an unofficial "graylist" made up of some of the 60,000 people identified by HUAC within their over a million dossiers of information. Reasons for inclusion on the graylist ranged from confusing screenwriter Louis Pollock with another man named Louis Pollock who had refused to cooperate with HUAC to director Joseph Losey, who turned down the chance to direct a movie called I Married A Communist, which turned out to be a test used by RKO to identify supposed Communists. Some on the graylist found work in less reputable areas, such as composer Elmer Bernstein, who eked out a living scoring "sci-fi cheapies" such as Cat-Women of the Moon and Robot Monster.

Omission and heartbreak

In 1952, as explained in Andrew Spicer's Historical Dictionary of Film Noir, the Screen Writers Guild, founded by three future members of the Hollywood Ten and formerly known as a relatively politically radical group, authorized studios to omit the names of anyone who hadn't cleared themselves before Congress from screen credits. This meant that not only could those accused of holding Communist beliefs or sympathies no longer find jobs in Hollywood but that the work they'd already done before being blacklisted would no longer be recognized as their own.

There were personal costs to those associated with the blacklist that went beyond losing one's job. Bartley Crum, a lawyer who had defended some of the Hollywood Ten in court, had his phones tapped and was under constant FBI surveillance, lost most of his clients, and eventually committed suicide in 1959. Screenwriter Richard Collins and actress Dorothy Comingore famously and dramatically divorced when Collins, a former Communist, decided to be a "friendly witness" for HUAC and named names while Comingore (pictured above) continued to refuse to do so. She lost custody of her children to her ex-husband after her stint as as "unfriendly witness" at trial, as described by Kathleen Sharp in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The end of the Hollywood blacklist

The Hollywood blacklist began breaking in the mid- to late '50s. As Ceplair notes in his Film History article, producers never admitted that they were engaging in blacklisting, so there was no way to officially call an end to the practice. It happened gradually via one-off instances of studios and the public ignoring the so-called rules of the blacklist.

In 1956, blacklisted director Jules Dassin, who had moved to Europe and continued his career there, released the movie Rififi, and it played in New York for 20 weeks without incident, save for a quote in the film's New York Times review: "Boy, what would they have done to this picture if it had been put up to Hollywood's Production Code!" Further cracks in the blacklist came from television producers, such as Alfred Hitchcock hiring blacklisted actor Norman Lloyd for Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Finally, in January 1960, Otto Preminger became the first in film to ignore blacklisting protocols when he announced that Dalton Trumbo was the screenwriter for his upcoming movie Exodus. Six months later, The New York Times announced he would be credited as the writer of the upcoming movie Spartacus, which he had been writing under a pseudonym. The Writers Guild of America went on to pursue correction of screen credits for blacklisted writers. Dalton Trumbo, who died in 1976, finally received the Oscar he'd earned for The Brave One in 1975, and in 1993, he received posthumous credit, including the Oscar for Best Screenwritng, for his work on Roman Holiday.