The Messed Up Truth About The Lewis And Clark Expedition

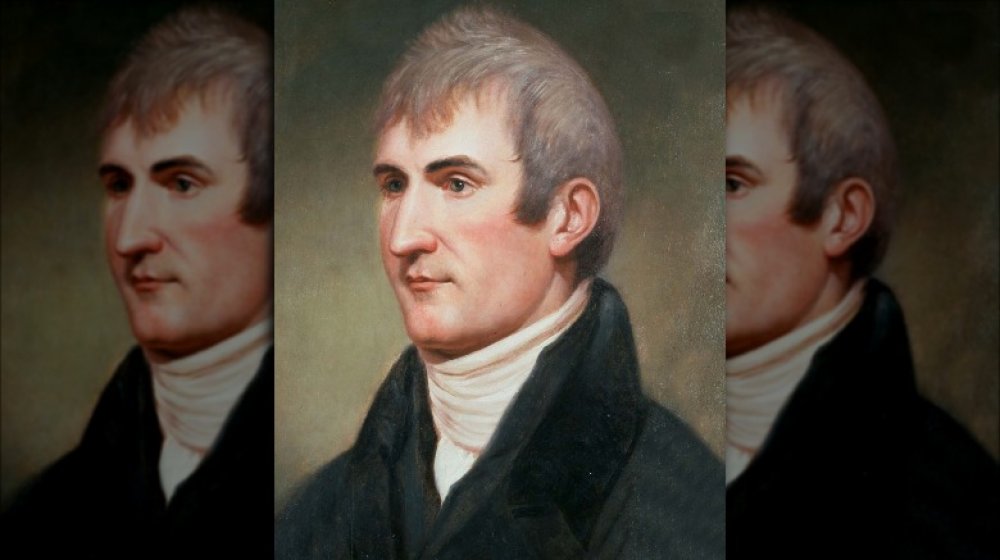

It's a story many American children are familiar with. President Thomas Jefferson had just bought millions of acres of land from the French — the famous Louisiana Purchase — and he needed someone to go explore this wild western territory. To that end, he recruited Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who gathered a team of brave men to go on a journey to the Pacific and back. The Lewis and Clark expedition, or the "Corps of Discovery" as it was known at the time, closely documented the flora and fauna of the uncharted West and befriended the many Native American tribes they met along the way. In particular, they made friends with the young Sacagawea, who served as a guide and translator for the Corps.

This common story, while not entirely false, is highly inaccurate. The real expedition was far more brutal — from violent conflicts with Natives to the whipping of enlisted men. This article will fill you in on all the grim details you weren't told about in school.

Lewis and Clark spread the message of American imperialism

As Lewis and Clark prepared for their expedition into the western territories, the United States government gave them numerous goals to accomplish. Foremost, they were to find a "Northwest Passage" of water that connected the rivers of the Atlantic to the rivers of the Pacific, allowing for continuous water travel across North America. (The men would fail this mission, as the Northwest Passage turned out to be a myth.) Furthermore, they were to keep detailed records of the plants and animals of the West and to map out as much of the territory as possible.

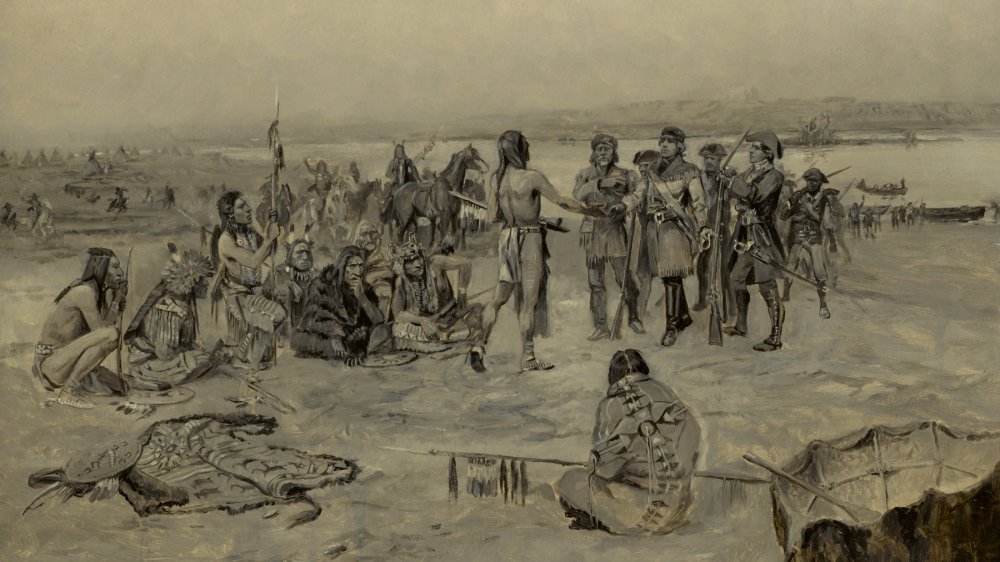

But an often-ignored goal of the Lewis and Clark expedition was to gain the loyalty of the Native American tribes of the West. As the Corps of Discovery encountered new tribes on its push to the Pacific, they informed the Native people that they were living on land that was now part of the United States. According to the University of Virginia, Lewis and Clark would offer gifts to the tribes — from knives to peace medals — and encourage the Native people to obey their new "Great Father" in the East (a patronizing reference to President Jefferson). But the Corps of Discovery also demonstrated the steep price of disobeying the United States: In front of each tribe, they would fire off their guns in a display of military power.

Lewis and Clark forcefully punished disobedient men

Lewis and Clark knew that their dangerous voyage required obedient men. So, in the early stages of the expedition, the two captains decided to construct an impromptu legal system whereby they would court-martial and punish any members of the Corps who disobeyed orders. According to the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, numerous enlisted men were penalized under this disciplinary system, especially in the first year of the expedition.

The crimes that these men had committed ranged in type and severity. John Collins was accused of "getting drunk on his post." He pleaded not guilty, but a jury of his peers disagreed. Collins was sentenced to receive 100 lashes on his bare back. Another man, Alexander Willard, was also sentenced to 100 lashes — his crime was falling asleep while on guard duty. Even worse, Willard's lashes were spread out over the course of four days, which was intended to intensify the pain. But perhaps the worst punishment went to Moses Reed, a man who attempted to steal a rifle and desert the Corps. Once he was caught, Reed was forced to "run the gauntlet" between the enlisted men as they whipped him with switches, and he was subsequently dismissed from the Corps.

Lewis and Clark's men ate horses and dogs

The diet of the Corps of Discovery was diverse and unusual. According to PBS, the Corps departed with "nearly 7 tons of dry goods, including flour, salt, coffee, pork, meal, corn, sugar, beans and lard." The men particularly loved meat and would hunt for elk and buffalo whenever they could. Luckily for them, animals were abundant across much of the Great Plains. When the men found themselves running low on food, they often obtained more by trading with Native tribes in exchange for tools and weapons. And, along the way, Sacagawea helped the Corps identify which plants were edible and which were not.

But some moments of the journey proved to be more desperate than others. Journals from the expedition reveal that the protein-starved men ate horse meat on numerous occasions (although it probably came from wild horses, not the ones that they rode upon). If that's not bad enough, animal lovers might cry when they hear that the Corps of Discovery frequently obtained dog meat from trading with Native tribes. Some of the men actually began to like the taste of dog and continued to trade for dog meat with the Natives along the Columbia River — ignoring the fact that the Columbia teemed with salmon. Besides unusual meat, when food ran out in one particularly rough situation in the Rockies, the starving men were prepared to eat candle wax – but it's unclear if it ever came to that.

Illness abounded, and laxatives were the "cure"

In their trek across the western United States, the men of the Corps of Discovery fell prey to a variety of illnesses and injuries. One man became severely ill in the first few months of the trip and died shortly after: This was Sergeant Charles Floyd, who, according to modern historians, likely succumbed to a burst appendix. After Floyd's death so early in the mission, Lewis and Clark probably expected to lose many more of their men. But, surprisingly, Charles Floyd was the only member of the expedition to die during the entire three-year journey, according to PBS.

Of course, many other men did fall ill during the voyage — and the worst part about getting sick in the early 1800s was that the treatment was usually worse than the illness. To treat their men, Lewis and Clark primarily relied on a powerful mercury-based laxative. These pills were colloquially known as "Rush's Thunderbolts" after Benjamin Rush, who manufactured them. But these pills rarely helped. In fact, the mercury often made the men sicker than they were before. Interestingly, though, Smithsonian Magazine reports that modern historians have been able to track the exact voyage of the Lewis and Clark expedition by looking for mercury deposits left behind by the men's stool. Isn't science neat?

There were many tense moments with Native tribes

For the most part, Lewis and Clark's men were able to stay on the good side of the Native tribes they encountered. There was only one violent conflict toward the end of their journey in 1806. But that's not to say that the Corps' men and the Native peoples were immediately best buddies — there were many tense interactions between the two groups.

One noteworthy example occurred early in the expedition, in the territory of the Lakota along the Missouri River. When Lewis and Clark met the Lakota, they immediately began preaching obedience to the new Great Father and displaying their military power. Then, after eating together, the Corps initiated trading with the Lakota, who were led by Chief Black Buffalo. But, according to the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, a sect of the Lakota who were rivals with Black Buffalo decided to create tension with the Corps, seizing the cable of a docked boat and demanding more goods. Clark escalated hostilities much further, drawing his sword and ordering his men to point their guns at Lakota. Thankfully, Black Buffalo intervened, reprimanding the Americans but ordering the Lakota to fall back. The Corps of Discovery stayed with the tribe for several more days, and the relationship remained mixed. Clark would later refer to the Lakota as "the vilest miscreants of the savage race."

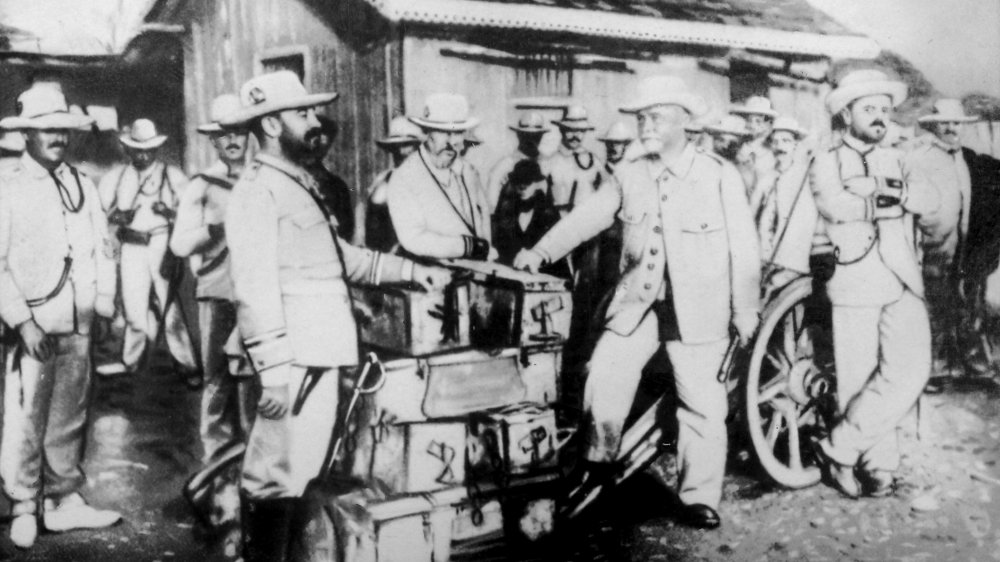

Spain sent many forces to intercept the Lewis and Clark expedition

Violent conflict with Native Americans wasn't the only threat that the Corps of Discovery faced. Unbeknownst to the Corps' men, the government of Spain felt that the expedition was an encroachment upon their territory and feared that it could be a precursor to further American expansion to the West. Although the United States government had purchased a massive amount of land from France, Spain still owned all the land west of the Louisiana Territory — as far north as modern-day Oregon.

So, when word about the expedition spread, the Spanish governor of New Mexico sent a force of 52 soldiers to intercept the men, per Teaching History. When the force reached the territory of the Pawnee, they learned that the Corps of Discovery had passed through the area but were long gone by that time. A second force of 100 men also failed to hunt down the Corps, as they were forced to return to New Mexico after a Pawnee attack.

Spain — refusing to give up — sent a third force of 300 men, but this group quickly fizzled as the soldiers turned against their commander. So, a final force of 600 men was mustered to capture Lewis and Clark and to persuade Native tribes in the region to side with Spain. Once again, this force failed. Without realizing it, Lewis and Clark had evaded the largest military force Spain ever sent into the Great Plains.

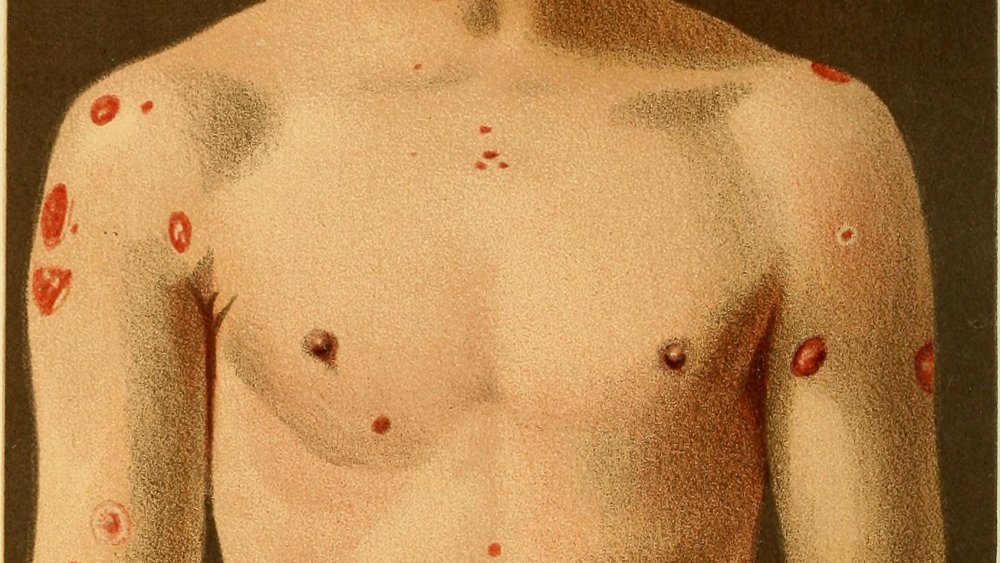

Lewis and Clark's men contracted venereal diseases

In spite of certain tense interactions, the Corps of Discovery was able to maintain friendly relations with most of the Native tribes they encountered. The Native peoples would show their hospitality in a variety of ways — dances and peace ceremonies were common. But one bonding practice had disastrous implications for all those involved. This was the practice of wife-sharing.

At the time, it was common for Native men to allow white visitors to sleep with their wives as a sign of goodwill — likely without regard for whether their wives consented or not. (Modern scholars write that most Native women were "eager to have sex with the men of the expedition," for what it's worth.) As we now know, wife-sharing led to the rapid spread of sexually transmitted diseases. According to National Geographic, many Native women in the West had already contracted STDs from sleeping with French and British traders. These diseases were then passed on to the men of the expedition. Lewis and Clark had prepared for their men to contract venereal diseases, but at the time, treatment options were limited. So, once again, the Corps found itself relying on good old mercury pills. (They didn't work.)

One conflict left two men of the Blackfeet Tribe dead

The Corps of Discovery was able to avoid outright conflict with most of the Native tribes they met. But that changed in 1806 when an encounter with the Blackfeet Tribe ended in tragedy.

On the return trip from the Pacific, Lewis and Clark decided that the men should break into smaller groups in order to survey more of the unexplored Western territories. Lewis took his crew up north, landing them in the territory of the Blackfeet, a Native tribe known for their military dominance in the region. According to PBS, Lewis' crew encountered eight Blackfeet men, who — after initial suspicion subsided — decided to camp with them for the night. But things went awry when Lewis informed the Blackfeet that some of their rival tribes, the Shoshone and Nez Perce, had already agreed to ally with the United States and would be receiving supplies and weaponry in return.

The Blackfeet felt threatened by the news that the power balance in the area was rapidly shifting. So, that night, the Blackfeet reportedly attempted to steal the Corps' guns. In the fight that ensued, Lewis reports that one of his men stabbed a Blackfeet warrior, while he personally shot another who was attempting to run off with the crew's horses. After the fight, two men were dead at the hands of the Corps of Discovery. According to Indian Country Today, "the Blackfeet closed off their territory to whites for the next 80 years."

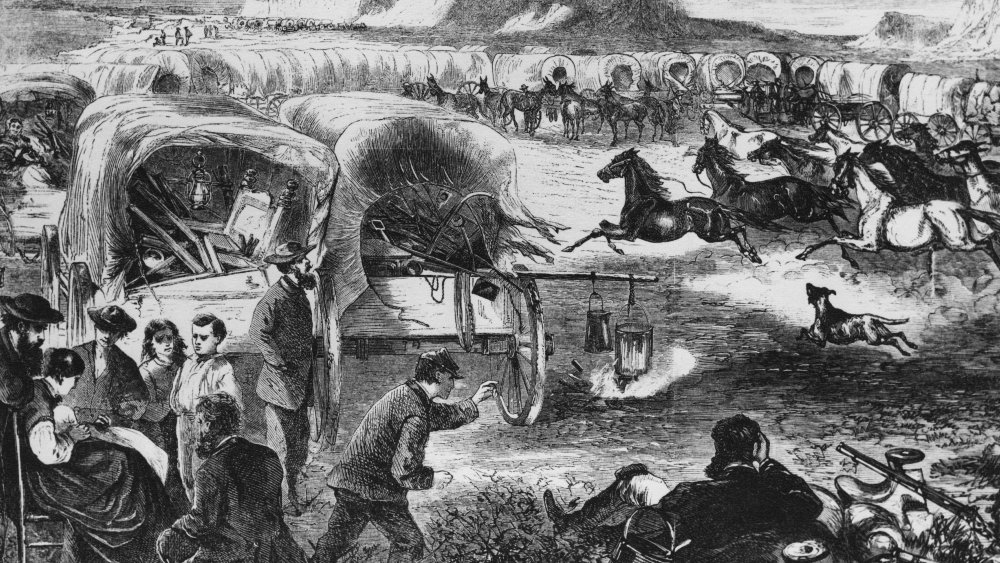

The Lewis and Clark expedition ushered in an era of conquest

It's been said that Thomas Jefferson thought it would take 100 generations for Americans to thoroughly settle the lands west of the Mississippi. The American people did it in under five.

After the conclusion of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1806, the westward expansion of the United States began in earnest. Throughout the 19th century, more and more territory was added to the U.S., while Native people were forcibly pushed further and further west. It's estimated that the Native American population declined from 600,000 in 1800 to a mere 237,000 in 1900. The land held by Native tribes suffered an even sharper decline.

It's unclear whether Lewis and Clark openly supported this brutal territorial expansion. The men had promised most of the tribes they encountered that they would be treated with respect by the U.S. government — but did they honestly believe that was the case? It's hard to say for sure. But we do know that Lewis and Clark's "daring" expedition west inspired many future settlers to do the same, per History, and that the geographic and scientific information they collected was of great benefit to America's future expansion.

The Lewis and Clark expedition's sole slave wasn't freed until much later

After completing their mission, nearly every member of the Corps of Discovery was given a generous reward. Besides monthly wages, each enlisted man received 320 acres of land, while Lewis and Clark both received 1,600 acres. While Sacagawea received nothing, her husband Charbonneau was granted the same payment as the other enlistees, according to PBS. But one man was left out entirely.

That man was York, the expedition's sole African American participant and personal slave to William Clark. As a slave, York was forced to join the Corps of Discovery against his will. Some of the expedition's men treated York with hostility: According to Smithsonian Magazine, one threw sand in his face, causing York to almost lose an eye. But as he traveled with the Corps, York was likely motivated by the hope that finishing the expedition could earn him his freedom, as slaves who went above and beyond for their masters were sometimes freed.

But when the mission concluded, William Clark refused to free York. In fact, York's request to be freed enraged Clark, who threatened to sell him to a more severe master in the South. Furthermore, The Washington Post writes that Clark denied York's appeal to be hired out to the farm in Louisville where his wife worked and even gave York a "severe trouncing" for his "insolent" behavior (in Clark's own words). Clark did ultimately free York some time before the 1830s, but he continued to claim that York preferred life as a slave.

Meriwether Lewis probably committed suicide after the expedition

Unlike York, Captain Meriwether Lewis was rewarded handsomely for his role in the Corps of Discovery expedition. Not only was he celebrated as an American hero and granted 1,600 acres of land, but President Thomas Jefferson personally appointed Lewis to be the governor of the new Upper Louisiana territory, according to PBS.

But honor did not bring Captain Lewis happiness. He'd been plagued by depression for much of his life — a mental illness that may have been exacerbated by neurosyphilis, according to some modern medical historians. His depression left him incapable of completing a journal of his expedition, which disappointed President Jefferson. To add insult to injury, Lewis' dealings with the War Department left him in steep debt, so he took a trip to Washington D.C. to sort out his financial situation. In 1809, in a remote inn on the route to Washington, Meriwether Lewis committed suicide. He was 35 years old.

But, as Smithsonian Magazine explains, the circumstances surrounding Lewis' death have led some to speculate that he was actually murdered. Lewis was found with gunshot wounds to both the head and chest, and the innkeeper's wife reportedly saw him crawling around before he died. It was also well-known that bandits roamed the area. Could Lewis have been the victim of a mugging gone awry? Possibly. But it's far more likely that his death was a tragic botched suicide: Lewis had composed his will before his trip to D.C. and had attempted suicide just a few weeks earlier.

Sacagawea also died at a young age ... Or did she?

As with Meriwether Lewis, there is some mystery surrounding the death of Sacagawea. Three years after the expedition had finished, Sacagawea's family accepted an invitation from William Clark to come live in St. Louis. According to the History Channel, Clark gave her and her husband Charbonneau some land to farm and offered their son Jean-Baptiste a Western education. But farming proved unsuccessful, so Sacagawea and Charbonneau joined a fur-trading expedition, leaving Jean-Baptiste under the guardianship of William Clark.

After this point, written records of Sacagawea's life become sparse. It is reported that she gave birth to a daughter, Lisette, in late 1812 and became fatally ill soon after. And according to the journal of fur trader John Luttig, "the Wife of Charbonneau [...] died of a putrid fever" on the evening of December 20, 1812. Historians have generally accepted this as Sacagawea's official death date. She was only 25 years old. William Clark adopted both Lisette and Jean-Baptiste the following year, but Lisette likely died as an infant.

However, fans of Sacagawea may have reason to hope. Sacagawea was not Charbonneau's only wife, so Luttig's journal entry is unhelpfully vague. Furthermore, Native American oral tradition says that Sacagawea left her husband and moved out west, eventually returning to the Shoshone Tribe in Wyoming, where she remained until her death in 1884. If this is true, then Sacagawea would have been in her nineties when she died — a happy ending for the most beloved member of the Corps of Discovery.