The Troubled History Of Benjamin Franklin

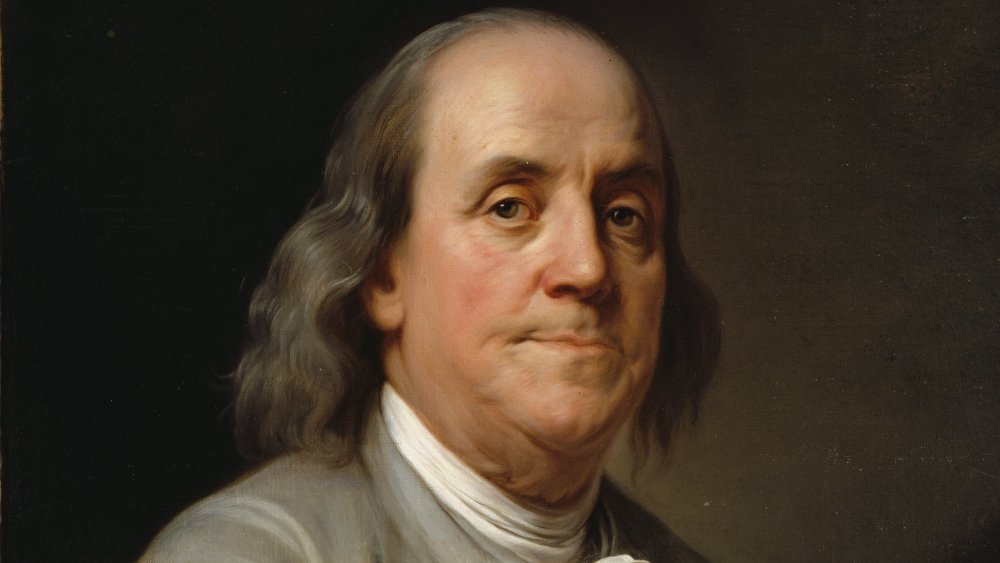

Benjamin Franklin is one of those historical figures who gets a bit lost in the telling. If you're American, you might think back to your school days, where you were told the tale of a wise old man who invented a bunch of things like bifocal glasses and also harnassed electricity. Perhaps you can recall some old painting that shows the Continental Congress gathering before an unsigned Declaration of Independence. Old Ben is probably somewhere in the foreground, looking sage and maybe like he's about to fall asleep.

While Franklin truly was an inventor and an occasionally sleepy dude, he was so much more than a first-grade story about flying a kite in an electrical storm. The reality is that Franklin led a deeply conflicted life. He was a brilliant polymath who often neglected his family in order to further himself. He was a British Loyalist until he suddenly wasn't. He was a renowned man of letters who bullied his fellow printers and maybe helped to birth the legend of the Jersey Devil. He was a Founding Father who probably let a doctor bury human bones in his garden. In short, he was complicated.

Some of the most exciting takes on Franklin dive into that complication headfirst and grapple with the dark side of his story, no matter how many $100 bills carry his smiling face. If nothing else, Benjamin Franklin gives us plenty of troubled history to contemplate.

Benjamin Franklin was a grammar school dropout

For a man who could rightfully be called America's first nerd, Franklin didn't have much success with formal schooling. In fact, one of the greatest minds of the American Revolution didn't even make it out of primary school.

Now, this wasn't Ben's fault. From an early age, it was clear that his mind was more than up to the task of spelling and sums. The problems started when finances came into play. It turned out that his parents, Josiah and Abiah, could only afford to send him to the Boston Latin School for two years, according to the introduction of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. After that, the boy talked vaguely about going out to sea, while his mom and dad talked equally vaguely, it seems, about preparing him to be a clergyman. Ultimately, he ended up as the shop boy for his father's candle-making business.

What's a bright young polymath supposed to do when he's been denied a formal education? School himself, of course. In a world without standardized testing, the expectation of college, or even something as seemingly basic as a résumé, Benjamin found he could get on just fine with books.

Franklin found writing success, but only while pretending to be a sassy widow

Young Ben Franklin moved on from his dad's candle shop to the world of his brother James' Boston print shop. Like many young men of the time, he was an indentured apprentice. Indentured children, says The Journal of Economic History, were typically bound to their workplace by a legal contract that required years of commitment.

At least Franklin was working in the world of letters, which clearly satisfied his drive to learn. Indeed, he began writing at a relatively young age, but no one seemed interested in publishing this nobody's work. Therefore, young Ben hatched a plan that makes it sound like he was about to go Mrs. Doubtfire on colonial Boston. If no one was going to publish a newcomer named Benjamin Franklin, they might publish a sharp-tongued widow named Silence Dogood. And, boy, wasn't it convenient if Silence Dogood left her letters on the steps of James Franklin's shop? All the easier for her to get published in his newspaper, the popular New-England Courant.

Mrs. Dogood became a hit. According to the Massachusetts Historical Society, publishers never believed that Silence was a real woman. But, when Ben revealed that it had been him all along, it created animosity between him and his possibly jealous brother, James.

Ben Franklin got a career boost after his brother was jailed

James Franklin's newspaper, The New-England Courant, was a popular and truly independent publication at a time when the press business was booming, says American Antiquarian.

Things were looking up for James' print business until the summer of 1722. That's when he printed an article that kind of implied that the colonial government was lax when it came to apprehending pirates. According to the Massachusetts Historical Society, that was enough for the local General Court to throw him in jail for the remainder of their legislative session. While James sat around in jail, it was up to the 16-year-old Benjamin to keep the print shop up and running. He did so for three weeks.

1723 wasn't much kinder to James and his print shop, reports the National Archives. That year brought a court order to stop publishing altogether, after the Courant was found to be mocking religion and local officials. James found a loophole by publishing everything under Benjamin's name while he went into hiding. Before he was even 20, Ben could claim to have worked as a newspaper publisher on two different occasions. All that had to happen was his brother landing in serious legal trouble.

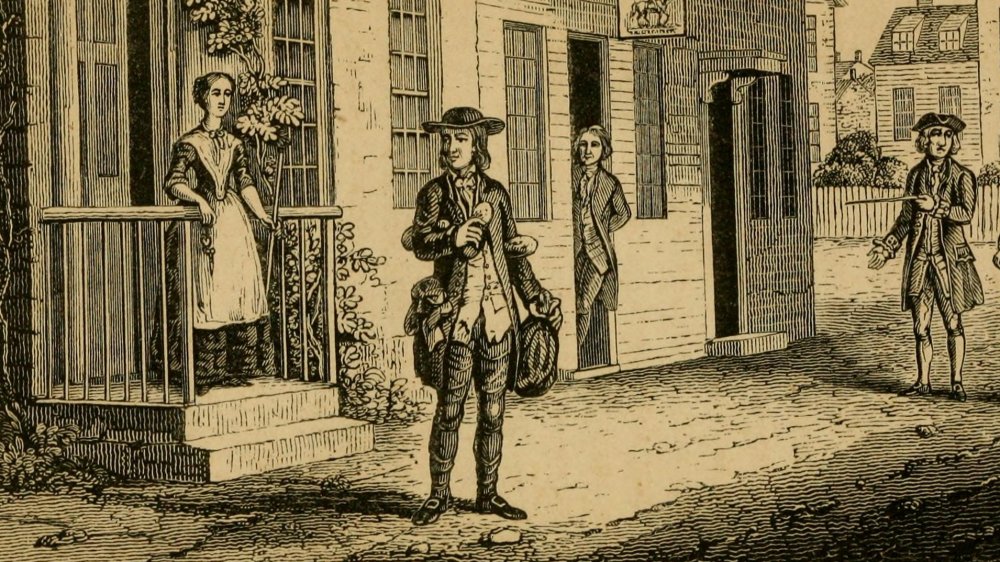

Benjamin Franklin was a teenage runaway

It's clear that Ben Franklin and his older brother, James, had a difficult relationship. According to sources like The Unfinished Life of Benjamin Franklin, James could be downright abusive, berating and beating his younger brother. That wasn't necessarily out of the ordinary for indentured apprentices, who could be forced to endure rough conditions in the hopes of a good career.

As the old apprentice agreement expired, James proposed a new term of servitude that would be kept secret. This struck Ben as odd and exploitative, but as he wrote in his own letters, he signed anyway. He later argued for his own freedom, claiming "resentment for the blows his passion too often urged him to bestow upon me." James resisted. But when you're a teenager who's had enough, at least in your own estimation, a recalcitrant older brother isn't much of a hurdle. At just 17 years old, Ben Franklin ran away from the print shop to Philadelphia, then one of the biggest cities in the colonies.

James would later admit that he might have been too harsh on his brother. In his autobiography, Ben says that James "was otherwise not an ill-natur'd man: perhaps I was too saucy and provoking."

Ben Franklin could be a real bully

Benjamin Franklin left a lot of printed material, which has been a boon for historians. It has also left behind an awkward legacy that has been hard to ignore. Benjamin got some of his earliest print work done through almanacs, which essentially mashed up calendars, agricultural information, and a touch of literature. According to the journal Early American Literature, almanacs were pretty trendy in the pre-Revolution colonies. They also generated a ton of competition and what amounted to an endless series of 18th-century diss tracks shared among printers.

Ben never held himself above the fray. In 1732, says Skeptical Inquirer, he started publishing Poor Richard's Almanac. This eventually led into a fight with a rival almanac printer, Titan Leeds, whose family had been publishing almanacs since the 1600s. Franklin took a humorous tack, predicting Leeds' death. Titan, meanwhile, didn't seem to think jokes about his impending doom were all that funny and printed a response in the Leeds Almanac. Thus, a feud was born.

Franklin kept pretending that Titan was already dead, claiming astonishment that his ghost was still kicking around the old printing press. There's even speculation that Franklin, who referred to the dragon-encrusted Leeds family crest as a "Leeds Devil," inadvertently spawned the legend of the Jersey Devil. According to NJ.com, Franklin's somewhat boorish taunts may have been revived by a 20th-century showman as the now-infamous cryptid haunting the New Jersey wilderness.

Benjamin Franklin had a rocky relationship with his wife

Poor Deborah Read. It's bad enough that she's been largely ignored by history. Worse, she was often discarded by her own husband. According to the Encyclopedia of Women in American History, Deborah was from a Philadelphia family who happened to give lodging to a 17-year-old Ben Franklin. Sparks started to fly between the two, but Deborah's family was skeptical about the scruffy runaway.

After some on-again, off-again travails that included Deborah's marriage to another man, the pair decided to rejoin, says History. The only issue was John Rogers, the first husband, who had gone missing in the Caribbean. A missing husband could still be an alive, legally entangled one, and Franklin apparently didn't want to mess with bigamy. Though Deborah and Ben would enter into a common-law marriage that lasted over 40 years, they never officially wed.

Those four decades held plenty of upset. Their first son, Francis, died at only four years old of smallpox. The matter of whether or not he had been inoculated may have created lasting marital discord, says Smithsonian Magazine. Franklin often took years-long overseas trips, reports The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Toward the end of Deborah's life, he kept sending home letters delaying his return, until it was finally too late. Deborah died of a stroke in 1774, while Franklin was still in London.

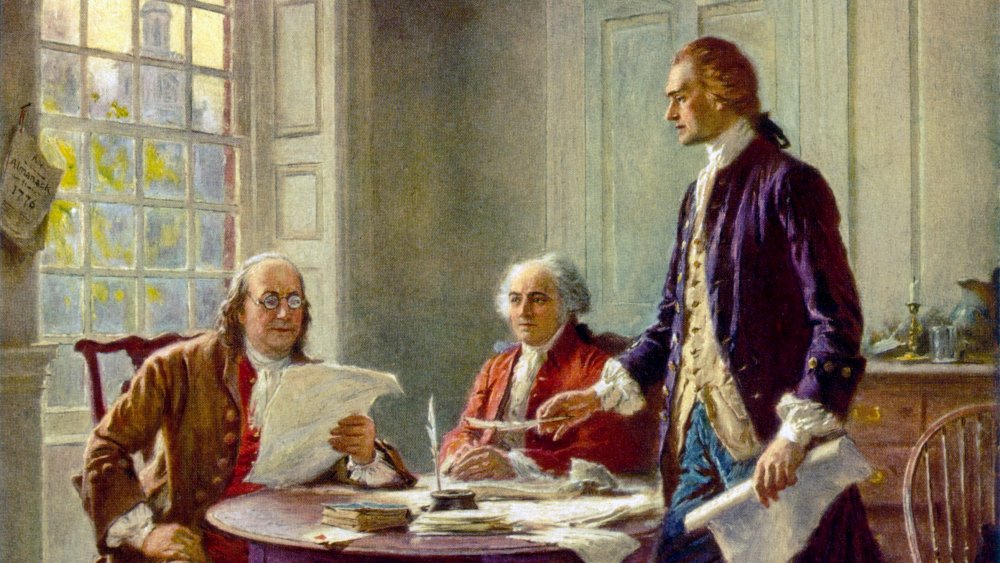

Franklin had to be dragged into the Founding Fathers club

Ben Franklin was pretty comfortable under British rule. He had held royal appointments and traveled back to England before the American Revolution, says History. Franklin clearly wasn't ready to run afoul of a system that had benefited him for so long. When tensions started to rise in the lead-up to the American Revolution, Franklin at first advocated for peaceful compromise. In his own words, he argued that "every mistake in government, every encroachment on rights, is not worth a rebellion."

So, what finally pushed him to the other side? Franklin himself could be frustratingly silent on the matter. John Adams, as quoted in Our Lives, Our Fortunes, and Our Sacred Honor, wondered how everyone could love old Ben when he spent so much time "sitting in silence, a great part of the time fast asleep in his chair." Ultimately, says Smithsonian Magazine, the thing that pushed Franklin over the edge was probably the way in which the colonies' "middling people" were treated so poorly by their governors. All those taxes broke his Loyalist resolve. He was, finally, a patriot.

Even when he finally crossed over to the revolutionary side, many suspected he was still a British spy, says the International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. Ultimately, Franklin proved to be loyal to the cause, but it's understandable why so many were skeptical about his true allegiance.

The Revolution destroyed Franklin's relationship with his son

In his early life, Benjamin Franklin had fathered a son out of wedlock, named William. Though Franklin acknowledged William as his son, the American Revolution eventually ruined their relationship.

As he grew, William had seen to it that he would become a proper Loyalist, just like Dad. According to The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, that eventually led to a plum job as the royal governor of New Jersey. When Benjamin Franklin finally changed sides to support the revolutionaries, his son remained a steadfast supporter of the crown. Even when Ben was hounded by other Loyalists, William remained in his post. They continued on in this way, with William supporting England and Ben backing the emerging United States, for years. In 1776, colonial militiamen imprisoned William for two years, says Pennsylvania History. His father appeared to do nothing to defend him. October 1781 brought the surrender at Yorktown and the approaching end of the war. William moved to England soon after.

Though father and son met a few more times before Benjamin's death in 1790, their relationship was irrevocably broken. In his final will, Franklin gave William very little. As quoted in A Benjamin Franklin Reader, he said, "The part he acted against me in the late war, which is of public notoriety, will account for my leaving him no more of an estate he endeavored to deprive me of."

Benjamin Franklin was an absent father

Before and after the American Revolution, Ben Franklin was busy doing the diplomatic thing overseas, reports American Diplomacy. This was obviously important work, but it made him a stranger to his own family. Often, he was gone for years at a time, fielding letters from his family asking when Father was going to finally come home. His relationship with his daughter, Sarah, often called "Sally," was strained thanks to this distance and his apparent disregard for her wishes. The tension is still plain to see more than 200 years later.

Take the issue of Sally's marriage. As told in Benjamin Franklin and Women, young Sally had her heart set on a merchant named Richard Bache. Conveniently forgetting his own early history, Benjamin raised concerns about Richard's financial stability. Sally's mother, Deborah, allowed the marriage to go forward anyway — it wasn't like her husband was there to stop it. For a year after the wedding, Franklin refused to acknowledge that he had a son-in-law at all. Eventually, he at least warmed up to their union and even lived with their family in his old age.

When Ben decided to take his grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache, overseas on a European diplomatic mission, it caused further upset. Sally argued, saying that the passage was dangerous for the young boy. Still, there was no resisting the paterfamilias. According to George Washington's Mount Vernon, the younger Benjamin accompanied his grandfather for an extended trip beginning in 1776, his mother's concerns largely ignored.

The basement of Franklin's London home shows his creepy side

Prior to the American Revolution, Benjamin Franklin lived in London as head of the Pennsylvania delegation to England, according to the Benjamin Franklin House. He traveled far and wide, at one point staying away for over a decade. Much of that time was spent at 36 Craven Street, still standing in London as the Benjamin Franklin House. With his intellect and charm, Franklin had no problem making connections in British society and politics. He has also been lauded for his scientific interests that resulted in a slew of well-known inventions, says The Franklin Institute.

That insatiable curiosity may have had a dark side. In 1998, workers began the long process of conserving the history of 36 Craven Street, says the Benjamin Franklin House. While excavating what had been the garden, the team made a shocking discovery: the bones of more than 15 people. Even more alarming was confirmation that the bones date from Franklin's time there. They also showed clear evidence of dissection.

The evidence, says Smithsonian Magazine, doesn't point directly to Franklin. All of those human remains were probably connected to an underground anatomy school led by William Hewson, a young doctor. Franklin isn't totally in the clear, however. He was a mentor to Hewson and may very well have known what was going on in his own home.

Benjamin Franklin didn't bother with marital fidelity

Ben Franklin must have had a powerful charisma to go along with his deep intellect and apparently boundless energy. Yet, his life story also points to a self-regard that sometimes eclipsed the needs of his friends and family. Deborah, his common-law wife of 44 years, must have suffered knowing that her husband was both a brilliant man and an inveterate skirt-chaser. Franklin often acknowledged his strong amorous desires and, per Biography, was even scared of them. The pure force of his libido was such that it brought him into contact with "low women" and other bad company.

A young Franklin was apparently quite the hell-raiser when he first visited London in 1725, reports the Chicago Tribune. Even as he grew older, his reputation for wooing the ladies followed him. During his post-Revolution time in Europe, a popular verse said that he "is too ready to engage / When younger arms invite him."

The smoking gun of this story has to be a letter that Franklin's family and associates tried to suppress for centuries. Written in 1745, "Advice to a Young Man on the Choice of a Mistress" was first published in 1926, says the National Archives. In the letter, Franklin addresses a friend on the need for caution when selecting a mistress. "You should prefer old Women to young ones," he says, because they are generally more interesting people and rarely have the pesky side effect of producing illegitimate children.

Sometimes, Ben Franklin was just too weird for society

At least a few of Ben Franklin's wild notions went over well at parties. Franklin's interest in electricity was a genuine scientific endeavor, for instance, but why wouldn't he use it to impress Philadelphia society at the same time? According to Atlas Obscura, Franklin was entranced by the showmanship of Dr. Archibald Spencer, who had a kind of stage show where he played around with electricity. Franklin took on the tricks himself and elaborated on a few, including one prank where he created an electrical "spider" and, says Cabinet magazine, an electrified portrait of King George II.

In Europe, Franklin may have been in attendance at meetings of the infamous "Hellfire Club," a gentleman's club that has been subject to lots of scandalous rumor. According to The Hell-Fire Clubs, there isn't much to the tales of Satanic rituals and secret societies. There was some merry blasphemy involved, like playing cards on a Sunday, but not much else. Did Franklin ever attend a meeting of the Hellfire Club? Maybe, says History, but he might have been disappointed that the legend didn't live up to reality.

After all that, Franklin's habit of "air bathing" seems positively family-friendly. It wasn't, of course. That's because air bathing is a euphemism for walking around nude. Franklin's variation on the theme was to sit about sans clothing near his open ground-level window, says Smithsonian Magazine. No word on his neighbors' reactions.