Tragic Details About The Marx Brothers

Combining razor-sharp wit with wacky, slapstick antics, Groucho, Chico, Harpo, and Zeppo Marx defined comedy for a generation. At the peak of their popularity, the Marx Brothers brought Depression-era audiences the irreverent and subtly subversive laughs they needed. Born into a family of performers and musicians, the Marx brothers developed their patented comedy act on the vaudeville circuit.

Originally part of a musical act, the brothers' comedic skills soon eclipsed the songs. As their trademark personas emerged, the Marx Brothers soon outgrew vaudeville. By 1924, they made the leap to Broadway with their musical comedy revue I'll Say She Is. Two more Broadway hits followed: The Cocoanuts in 1925 and Animal Crackers in 1928. However, not even the Great White Way could contain the Marx Brothers' mayhem for long. By the decade's end, Hollywood was calling, and the four comedians were more than ready to make the leap to the silver screen. The new medium of talking pictures would prove the perfect vehicle for the Marx Brothers' hilarious wordplay. Beginning with 1929's The Cocoanuts (based on their successful Broadway musical), the Marx Brothers would spend the next two decades making some of the greatest comedy films of all time.

Nevertheless, the story of the Marx Brothers isn't all chuckles and pratfalls. From their hardscrabble upbringing to their legendary legal troubles, the Marx Brothers faced more than their share of heartache. These are the tragic details behind the hilarity.

Firstborn Marx Brother Manfred died in infancy

Long considered a myth, even among members of the family, rumors of a sixth Marx brother were finally confirmed by Maxine Marx, daughter of eldest brother Chico, in her 1983 book Growing Up With Chico. Manfred Marx, nicknamed "Mannie," was the firstborn son of parents Sam and Minnie Marx. Surviving for only seven months, Manfred died on July 17, 1886. Although it was long assumed that the firstborn Marx brother passed of tuberculosis, asthenia and entero-colitis, complications which probably arose from influenza, are cited as the actual causes of death. Manfred Marx is buried beside his maternal grandmother, Fanny Schoenberg, in New York's Washington Cemetery.

Manfred's death had a profound effect on Sam and Minnie Marx which would translate into the mourning parents lavishing eldest surviving son Leonard, better known by his stage name Chico, with love and attention. Baby Manfred's sickness would also instill a heightened sense of parental vigilance in the Marxes. According to the website Marx-Brothers.org, Groucho Marx once recalled his mother saying, "Sam can cough all night and I never hear him, but if one of my boys coughs just once, I'm wide awake."

In memory of their lost child, Sam and Minnie Marx would bestow their youngest son Herbert, known to Marx Brothers fans as "Zeppo," with the middle name Manfred.

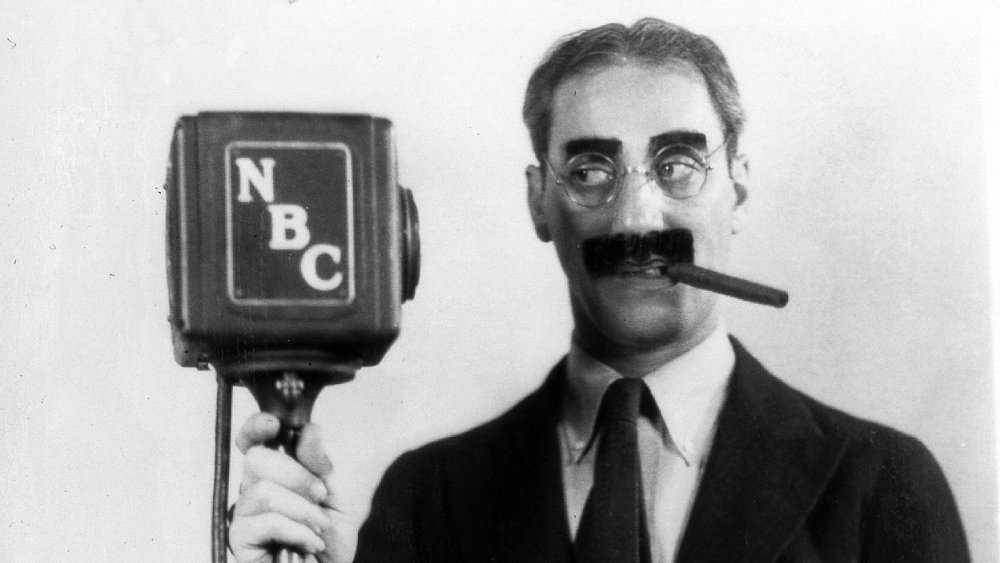

Poverty forced Groucho Marx out of school at age 12

Best remembered for his greasepaint mustache, ever-present cigar, and lightning-fast wit, young Groucho, born Julius Henry Marx, was an outsider in his own family. A middle child, he yearned for the approval of his parents but found himself overshadowed by brothers Leonard (Chico) and Adolph (Harpo). Unlike his siblings, Groucho loved school and threw himself into his studies, per Biography. Although he faded into the background at home, Groucho could shine in school, the praise of his teachers standing in for the parental affection he craved. Books were his comfort, and he dreamed of one day becoming a doctor.

Sadly, Groucho's academic ambitions were crushed by his family's dire financial circumstances. At only 12 years old, Groucho, at the behest of his mother, left school to help support his family. Put to work in a wig factory, Groucho's stint in the workforce was mercifully short. At 15, he joined the Leroy Trio, a traveling musical act. He would go on to sing with English performer Lily Seville as half of Lady Seville and Master Marx before joining the vocal group Gus Edwards' Postal Telegraph Boys. Ironically, the formerly unassuming Groucho would eventually find his greatest success with his brothers Milton (Gummo) and Adolph (Harpo) as a member of the Four Nightingales. During a particularly disastrous gig in Nacogdoches, Texas, in which the group was upstaged by a runaway mule, Groucho used his acerbic wit to put down an unreceptive audience. "Nacogdoches is full of roaches," Groucho quipped. To everyone's surprise, the sparse crowd roared with laughter.

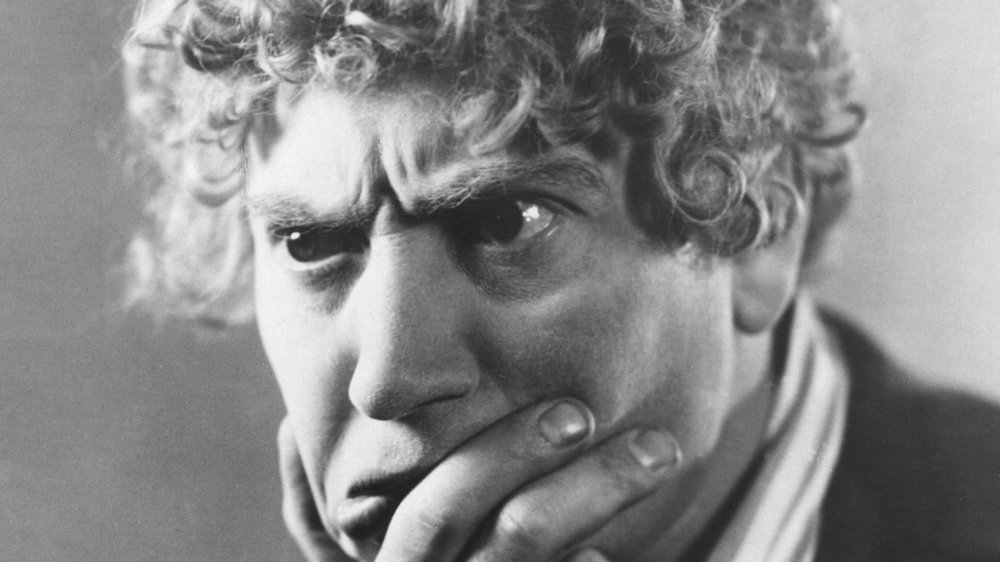

Young Harpo Marx was the victim of classroom bullies

Harpo, the Marx Brothers' silent master of physical comedy, was born Adolph Marx on November 23, 1888. One of a handful of Jewish kids growing up in a largely Irish and Italian neighborhood, young Harpo often found himself the target of persecution. Abuse from both bullies and a discouraging teacher who considered him "slow" led to his permanent exit from academia at age eight.

In his 1961 autobiography, Harpo Speaks!, Marx writes "[...] my formal schooling ended halfway through my second crack at the second grade, at which time I left school the most direct way possible. I was thrown out the window. There were two causes of this. One was the big Irish kid in my class and the other was a bigger Irish kid." Over the course of his abbreviated tour of the second grade, physical ejections from the classroom at the hands of his tormentors became commonplace. "I was the perfect Patsy," Marx explained. "I was small for my age. I had a high squeaky voice. And I was the only Jewish boy in the room."

Although Harpo may have suffered minimal physical damage from his bullies, the emotional anguish inflicted by his teacher left more lasting scars. "The teacher, a lady named Miss Flatto [...] liked to predict, in front of the class, that I would come to no good end, " Marx recalled. "This was the only matter on which the Irish kids agreed with Miss Flatto, and they saw to it that her prediction came true."

Chico Marx's gambling addiction

Chico Marx, born Leonard Joseph Marx on March 22, 1887, had a lifelong penchant for gambling. Over the course of his career, this vice would cost him dearly. According to Hollywood Stories by Stephen Schochet, Chico's gambling addiction began when the comedian was just nine years old. Family patriarch Sam "Frenchie" Marx, a tailor, discovered early on that he couldn't trust his eldest son with deliveries. Young Chico would pawn the garments and blow the cash in local pool halls and bars. As recounted in the 1993 television documentary The Unknown Marx Brothers, he even hocked his father's shears to pay off a gambling debt.

The Marx Brothers' success allowed Chico to indulge his habit at higher stakes. In a 2000 interview with L.A. Times journalist Robert W. Welkos (via SFGate), Chico's daughter, Maxine Marx, recalled the extent of her father's gambling debts. "When somebody asked Chico how much money he lost betting, he would say, '$2,640,239.27' or some figure he'd make up," Maxine said. "He would always include the cents." Toward the end of their careers, the Marx Brothers wound up making some of their less memorable films to get Chico out of trouble. Miriam Marx, daughter of Groucho Marx, explained how a desperate Chico would beg his brothers for assistance. "They are going to kill me! They are going to kill me!" Chico would say. "Then they made some lousy movie to save his life," Miriam stated.

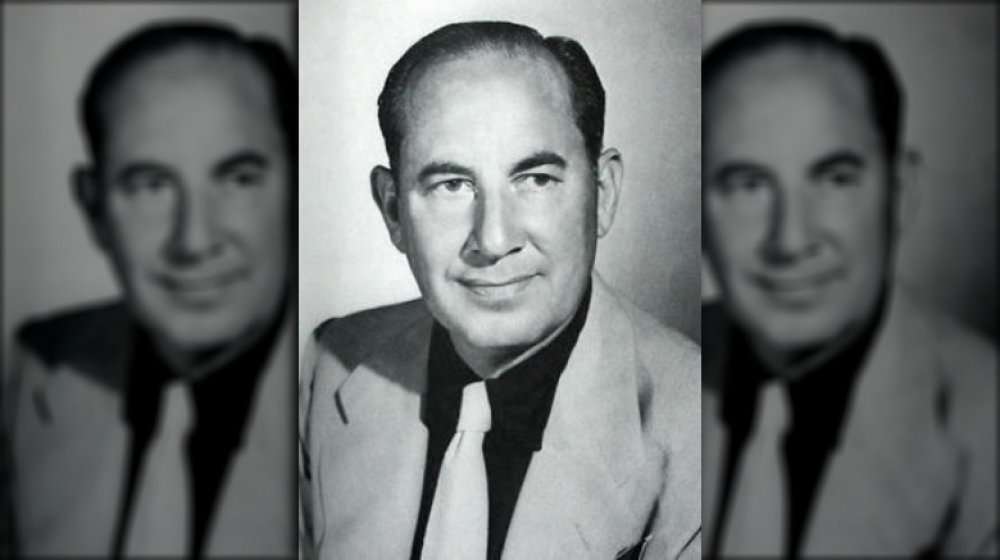

Gummo, the forgotten Marx Brother

Largely unknown to all but the most devoted fans, Milton "Gummo" Marx, born October 23, 1892, is the forgotten Marx Brother. Although Gummo was the first to enter show business as the dummy in an uncle's ventriloquism act and was the second brother to join the family act that would make the Marx Brothers famous, his tenure as an entertainer was short-lived. A talented dancer and comedian, Gummo, who got his stage name from the gum rubber overshoes he wore to cover his worn-out footwear, often portrayed a broad Jewish stereotype in the brothers' vaudeville act. After 11 years with the Marx Brothers, Gummo exited the act when he was drafted into the Army during World War I. Replaced in the Marx Brothers by younger brother Herbert "Zeppo" Marx, Gummo entered the garment industry, selling dresses and textiles, after the war. According to Marx-Brothers.org, Gummo was an industry innovator who held a patent for a laundry rack of his own design.

Gummo, however, eventually returned to show business and the Marx Brothers. After his dress business went under in 1933, Gummo apprenticed in the distribution arm of Universal Pictures before returning to New York to found the talent agency Marx, Miller, and Marx with younger brother Zeppo. In addition to the Marx Brothers, Gummo and Zeppo's clients included such big names as Lucille Ball, Jean Harlow, and Lana Turner.

Zeppo Marx's departure led to success and sadness

The youngest of the Marx Brothers, Herbert Manfred "Zeppo" Marx, appeared in the comedy team's first five films. Cast as the straight man, Zeppo never had the opportunity to develop as a comedian. Zeppo's long-simmering frustration led to his departure from the Marx Brothers after their final film for Paramount. As detailed in Monkey Business: The Lives and Legends of the Marx Brothers, Zeppo broke the news about his intentions to Groucho in a letter. "I have only stayed in the act until now because I knew that you, Chico and Harpo wanted me to," Zeppo wrote. "But I'm sure you understand why [...] and that you forgive my action. Wish me luck. Love, ZEPPO."

Zeppo became a successful talent agent, first on his own and then as part of Marx, Miller, and Marx with partner Allan Miller and brother Gummo. Disillusioned with show business, the mechanically inclined Zeppo left the entertainment industry in the 1940s to start an industrial engineering firm that specialized in the manufacture of aircraft parts.

Despite his professional success, Zeppo's personal life was turbulent. Twice divorced, his second wife, actress and former showgirl Barbara Blakely, left him in 1973 for Frank Sinatra after a torrid affair with the crooner. In 1978, Zeppo was ordered by an Indio, California, court to pay 37-year-old former girlfriend Jean Bodul $20,690 for physically assaulting her during an argument. Legal woes surrounding Groucho's estate would haunt Zeppo until his death from lung cancer in 1979.

Money disputes plagued the Marx Brothers' movie career

Although critics and fans agree that the Marx Brothers were at their unhinged best during their tenure at Paramount Pictures, the comedians' time at the studio was marred by financial disputes. According to writer and documentarian Robert Bader, author of the definitive Three of the Four Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage, creative accounting on the part of Paramount robbed the Marx Brothers of profits. Following the success of The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers, the brothers negotiated a deal which should have garnered them 50 percent of the net profits for their next two films, 1931's Monkey Business and 1932's Horse Feathers. Although both comedies were box office hits, the studio cooked the books to avoid paying the brothers their share. Paramount and the Marx Brothers fought the matter out in court for decades. Finally, in 1962, the Marx Brothers were awarded a $36,000 settlement.

After 1933's Duck Soup, the Marx Brothers parted ways with Paramount, and MGM head Irving Thalberg snatched the comedians up with a personal contract. The brothers successfully negotiated for 15 percent of the gross of their next film, A Night at the Opera, netting the greatest financial returns of their careers. However, that monetary success would ultimately come at the cost of their creativity. A Night at the Opera and its follow-up, A Day at the Races, shoehorned the Marx Brothers' mayhem into formulaic plots with the brothers featured as supporting players in their own films.

A Night at the Opera was the beginning of the end

The 1933 film Duck Soup marked a low point for the Marx Brothers. However, their fortunes would take a turn for the better in 1935. With a lucrative new contract with MGM and an ally in wunderkind studio head Irving Thalberg, the Marx Brothers were set for their greatest success with A Night at the Opera.

According to Brigham Young University film historian James D'Arc, MGM was in need of a comedy hit when it nabbed the Marx Brothers. Nevertheless, the studio wasn't willing to give them the free reign they'd enjoyed at Paramount. MGM was intent on fitting the brothers into a structured plot rather than merely turning them loose in front of the camera.

Featuring some of the Marx Brothers' best comedic bits, A Night at the Opera was a hit for MGM and a financial windfall for the comedy team. However, MGM's smoothing of the Marx Brothers' rough edges robbed the comic trio of the anarchic quality that was their hallmark. Scott Tobias of The Dissolve describes Irving Thalberg's reengineering of the troupe's act as the beginning of the end for the Marx Brothers. Where their early films portrayed the brothers as a force of anti-authoritarian chaos, A Night at the Opera relegated Groucho, Harpo, and Chico to supporting players — mischievous but kindhearted troublemakers in the service of MGM's stable of stars. Thalberg's gambit initially worked, but in the long run, it robbed the Marx Brothers of their unpredictable essence.

Harpo Marx's tragic passing

Harpo Marx performed for the last time in January 1963. Appearing opposite comedian Allan Sherman at the Pasadena Theater, Marx pulled out all of the stops with his classic bits. Then, as recounted by his son, Bill Marx, in the PBS documentary Make 'Em Laugh: The Funny Business of America, the silent comic stunned the audience with a surprise ending. "[...] at the very end, he picks up the microphone and he launches into his Bar Mitzvah speech," Bill Marx says. "The people are just silent. [...] And he comes to the end of this and he says, 'And, in conclusion, I am so honored to know that you folks have the keenness and the perspicacity for recognizing monumental genius. I thank you.' And walked off the stage. Well, people must have applauded for at least a good two or three minutes."

On September 28, 1964 — the date of his 28th wedding anniversary with wife Susan Flemming – Harpo Marx died at the age of 75 after undergoing an open-heart procedure. Groucho Marx wept at the funeral. According to his son, Arthur Marx, it was the only time he ever saw his father cry.

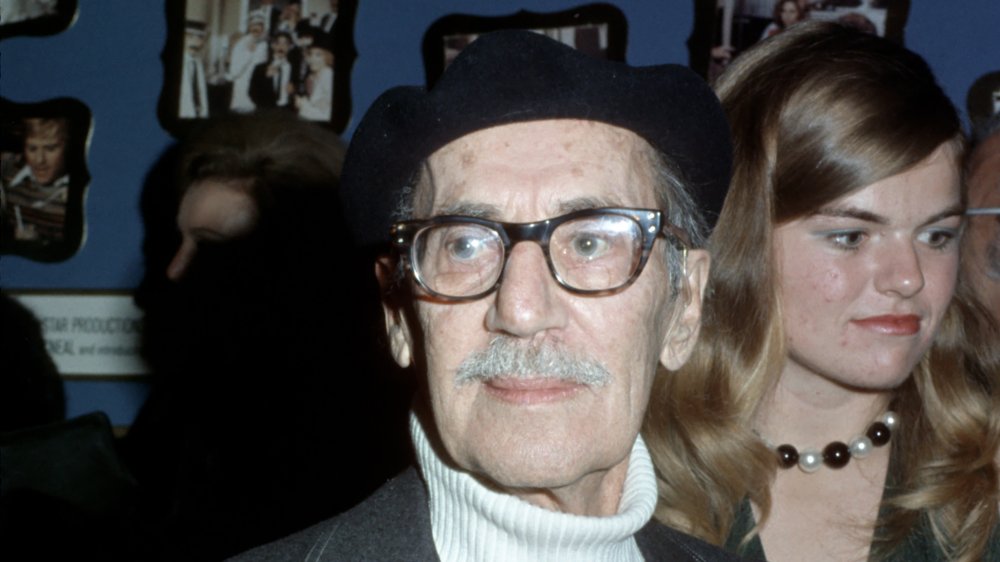

An ailing Groucho Marx was the victim of elder abuse

By the end of his life, Groucho Marx was in extremely poor health. Suffering from dementia, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and a host of other debilitating ailments, the aging comedian was no longer able to care for himself. Estranged from his children, Groucho's care fell into the hands of his companion and manager, Erin Fleming. Fleming, 51 years Marx's junior, was instrumental in engineering the comedian's comeback in the early 1970s.

However, the revival of Groucho's career was not without its dark side. Many of Groucho's friends accused Fleming of pushing him too hard, forcing an increasingly frail Marx to perform against his will for her financial gain.

As reported by PBS NewsHour, Groucho's son, Arthur Marx, filed suit against Fleming, accusing her of having a "harmful and destructive influence" on his ailing father. Groucho's nurses testified that Fleming administered overdoses of tranquilizers to the comedian and verbally abused him. Melinda Marx, Groucho's daughter, accused Fleming of attempting to alienate the star from his family. Fleming was eventually removed as Marx's conservator, but his family's legal woes with the former showgirl would continue long after Groucho's death from pneumonia in 1977.

Elvis Presley's death overshadowed Groucho Marx's passing

By the time of Groucho's death at age 86, the comedy star was an icon of pop culture. His trademark image from the Marx Brothers' heyday had become as familiar as that of Santa Claus and Mickey Mouse. Still, his passing on August 19, 1977, went largely unnoticed by the public. Just three days before Marx died, the world was shocked by the untimely passing of rock 'n' roll legend Elvis Presely from a drug-related heart attack at age 42. As millions of music fans went into a protracted state of mourning for the King, Marx was cremated and interred in Los Angeles' Eden Memorial Park.

More than 40 years after the stars' deaths, Groucho Marx's passing sadly remains a footnote in entertainment history. While the anniversary of Elvis' death is marked with yearly memorial celebrations, Marx is remembered only by dedicated fans of film and classic comedy.

Legal troubles plagued the Marx Brothers' heirs

The children of Groucho, Harpo, and Chico Marx spent many of the years after the passing of their famous fathers embroiled in intense litigation related to the immortal comedy troupe. At the center of these long-standing legal battles was the issue of the licensing of the comedians' likenesses. Surprisingly, these legal quarrels were just as often between the Marx children as with outside parties.

In 1981, the Marx heirs successfully filed suit against the producers of a Broadway play which included "performers simulating the unique appearance, style and mannerisms of the Marx Brothers.” However, in 2000, just as the Marx estates were coming to an amicable agreement on a proposed biopic about the comedy team, the estates of Chico and Harpo Marx came to legal blows with Groucho Marx Productions over a proposed Marx Brothers animated TV show. As of this writing, a Marx Brothers biopic has not been filmed.