How Erik The Red Became A Legend

In some respects, Erik the Red was a classic Viking. He loved to cause trouble, frequently appearing happy to bash his way through life on the way to achieve riches and fame. It's easy to picture him, standing on the prow of a longboat, steely-eyed, his red bread moving in the wind. People would hear his name and tremble.

Except Erik was not exactly a Viking. Among modern scholars, that term, as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, is used to refer to the violent raiders who terrorized Europe from the 8th to the 11th centuries. When the occasion called for it, they could also act as somewhat more peaceful traders. While they were definitely part of a dramatic history, Vikings don't represent the whole story of the Norse people. The Norse were a broader group of folks who originated in Scandinavia but, starting in the 8th century, started expanding out into the world.

So, to play it safe, we might be better off referring to the fearsome Erik the Red as a Norseman. Don't get too comfortable just yet. Even though we don't have records of this man raiding settlements, he seemed to have a talent for terrorizing people anyway. Erik's story is a dramatic one, full of violence, disasters at sea, and even the mysterious disappearance of an island full of people.

He moved to Iceland because of problems with the law

We first hear about Erik the Red in historical sources when he moves from the Jæren district of Norway to Iceland with his father, Thorvald. The pair moved because of "some killings" around 970, says the Canadian Encyclopedia, but it's not clear exactly how the father and son were involved. It must have been pretty bad, though, considering that a move from Norway to Iceland in the 10th century was no small undertaking.

It wasn't easy to find a good place where they could begin their new life. At this point in Norse history, Iceland was thoroughly populated, meaning all of the good farmsteads with prime grazing and crop lands were already claimed. Thorvald and Erik were also of little account, being newcomers and established troublemakers. Their social influence in this new-to-them land was close to nil.

All of this meant that they finally settled on a rather grim little piece of land called Drangar, according to The Saga of Erik the Red. There, at the cold northern edge of the island, crops didn't grow terribly well, but it was the best they could do.

The 'red' may have been a reference to his hair and his temper

The obvious explanation here is that Erik had red hair. Gingers were relatively common in Norse settlements, so much so that Thor, the god of thunder, was a redhead in some tales. Some scientists, as reported by The Scotsman, even claim that the appearance of red hair genes follow Norse trade routes into Ireland and Scotland, where red hair is most prominent today.

Given his eventual issues with violence, "the Red" may also be a reference to Erik's tempestuous nature. That could make him deeply unpopular with his fellow Norse people. Contrary to popular belief, not all Norse folks were violent Viking types. Many of them wanted to mind their own business on farmsteads and in small settlements. Lawmaking and conflict resolution were in effect at regular meetings known as or Þingvellir, or "things," says the Journal of the North Atlantic. A man with a difficult temper and a hyperactive sword hand would have trouble fitting in to this society for very long.

While occasional conflict amongst people resulted in fighting, few places would tolerate outright murder. And someone with Erik's supposed temper and propensity towards striking out at those who crossed him, was bound to run into trouble sooner or later.

Erik moved on up through marriage

In the world of the Norse, as in many other places, an advantageous marriage could make all the difference. After a while spent eking out a life on the barren northern coast of Iceland, Erik was ready to get on with his life. It seems that the right woman gave him a serious leg up in Icelandic society.

Enter the wealthy Thjodhild. Her family didn't worry about money and, once Erik married her, neither did he for the time being. Once Thorvald died, Erik moved south to the more pleasant Breidafjordur region. Thjodhild's stepfather owned a homestead there and let the married couple settle on a piece of his estate, as told in The Saga of Erik the Red.

Excavations of the site where Erik and Thjodhild likely lived showed the footprint of a modest farm, however. Things were certainly better than the bachelor pad Erik had established with his dad, but they weren't exactly the toast of Iceland's society, either.

More legal issues ruined his sweet spot

It seems as if Erik really did have a temper. Around 980, a dispute with a neighbor turned deadly. According to The Sea Wolves, some of Erik's thralls, or slaves, apparently started a landslide on a nearby farm belonging to a man named Valthjof. Eyiolf the Foul, a buddy of Valthjof, turned around and killed the thralls. Erik didn't like that, so he then killed Eyiolf and another involved man, Holmgang-Hrafn.

As a result, Erik was exiled for three years. He picked up and moved to the Isle of Oxney, near the British coastline in Kent. Before his departure, he had asked a friend, Thorgest, to take care of his setstokkr. As per Biography, these were ornamental house beams that had serious mystical power for their owners. When Erik finally returned to Iceland, he went to retrieve the setstokkr, but the sagas say that they "could not be obtained." Erik retaliated by taking someone's mystic house beams, but the sagas aren't clear whether they were his or those of the turncoat Thorgest.

As you may have already guessed, these actions resulted in more killing. When Thorgest came to claim the setstokkr, Erik slayed Thorgest's sons and a few other people besides. Eventually, Iceland's governing assembly outlawed Erik for another three years.

At least he knew how to use his exile

Most people seemed to wait out their exile quietly, carrying on their lives until their sentence was over and they could return. Erik, meanwhile, had already done that. Now, with the dubious achievement of his second exile, he was ready to take on a more active project.

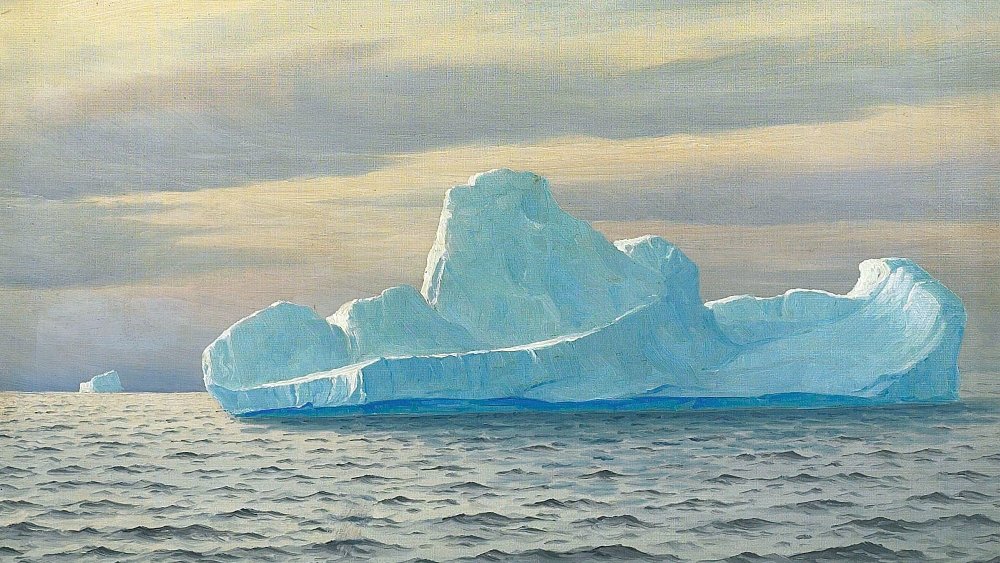

That meant sailing. Specifically, Erik had the idea to go west. It wasn't just a wild notion, either. Old reports from previous explorers had mentioned a huge island in that direction. The rigors of seafaring in the North Atlantic had made the passage difficult, however. Then again, if you had a whole three years of exile to while away, shouldn't you go for it?

So, Erik the Red, along with his family and a small group of men, set sail around 982, according to Encyclopedia Britannica. They sailed around the southern part of the land and made camp on an island at the mouth of a fjord, eventually called Eriksfjord and now known as Tunulliarfik Fjord.

Greenland made Erik see dollar signs

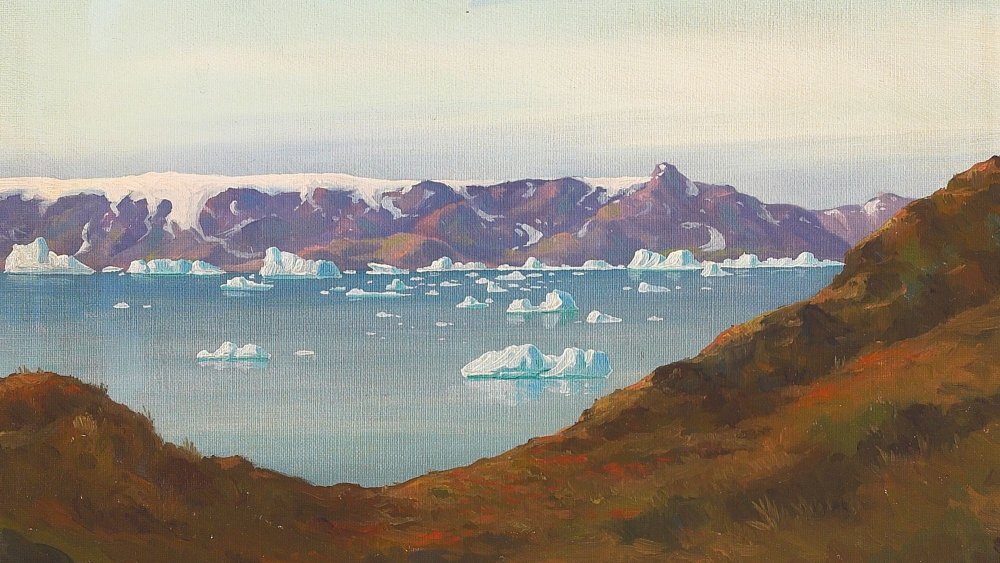

Erik's party spent the next three years exploring the huge island and naming a few spots. According to The Sea Wolves, he really did name the place Greenland as a sort of marketing ploy. That name, plus a few well-placed descriptions of animals to be hunted and land ripe for farming, would prove very attractive to future settlers.

None of the historical records say that Erik's group met native people. We now know Inuit people had already settled the north part of the island around 2500 BCE, says the June 2011 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. However, those people had left before the Norse arrived with Erik the Red. The Thule people, ancestors of the modern Greenlandic Inuit, appear to have moved in around the same time or even a bit later than the Norse settlers, says The Anatomical Record.

That bit about farming wasn't wild speculation, by the way. The Norse arrived in Greenland during the medieval warm period, described by Columbia University's Earth Institute as a time between 800 to 1200 CE when the globe's climate rose a few degrees above average. Crops grew well during this time, even at latitudes that would seem harsh to us today. Erik the Red wasn't being misleading when he sold people on a rich Greenland just waiting to be farmed. For a time, agriculture supported the Greenlandic Norse just fine.

Getting new settlers to Greenland presented a challenge

Now at the end of his exile, Erik sailed back for Iceland. He convinced a bunch of people to sail from Iceland to Greenland, but the journey would not be easy. In Iceland, Erik managed to secure 25 ships of people, says ThoughtCo. The passage proved difficult, however, and only 14 of those ships landed. Of the total party, only 350 people landed safely, including Erik and his family.

Part of the history of Norse Greenland was briefly chronicled in Íslendingabók, or Book of the Icelanders, written by a 12th century priest named Ari Þorgilsson. He claims that the new settlers found evidence of previous habitation, which they assume is connected to skraelings, their term for indigenous people. At the time, the land was apparently uninhabited, and so Erik started to parcel it off to people in his party. Ultimately, the Norse settled in two places: the Eastern Settlement and the Western Settlement, with a combined population of 2,000 to 3,000 people, says the Journal of the North Atlantic.

The people who made it across the North Atlantic enjoyed a fairly successful existence, at least in the beginning. Many farmed, while others made a living from the sea. Eventually, says the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Greenland started exporting goods like walrus ivory, narwhal horns, and even the occasional live polar bear. Erik the Red, it seems, had finally established a stable, prosperous life.

Erik wasn't cool with his son's crazy new religion

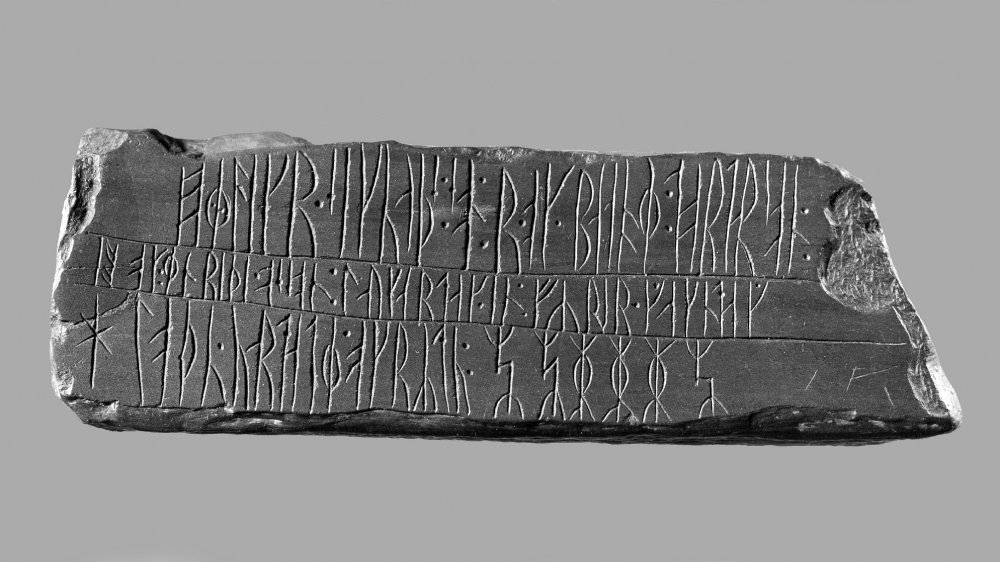

At this point in Norse history, Christianity was beginning to make some serious inroads into society. Vikings had already begun to encounter Christian ideas during their raids, says the BBC. In the middle of the 10th century, right around the time Erik was encountering all his troubles, Haakon the Good of Norway was trying to get Christianity started in his lands. Denmark's Harald Bluetooth was more forceful, at least according to his runestone, which states that he made all of the Danish people Christian during his late 10th century reign. For a time, pagan Norse beliefs and Christianity coexisted throughout this region, sometimes with ease, sometimes without.

Remote as it was, Greenland wasn't about to escape this wave of new religion. It appears that the source of this new belief was actually Erik's son, Leif, says The Viking Age. He brought Christianity to Greenland around the year 1000 after spending time at the court of King Olaf of Norway.

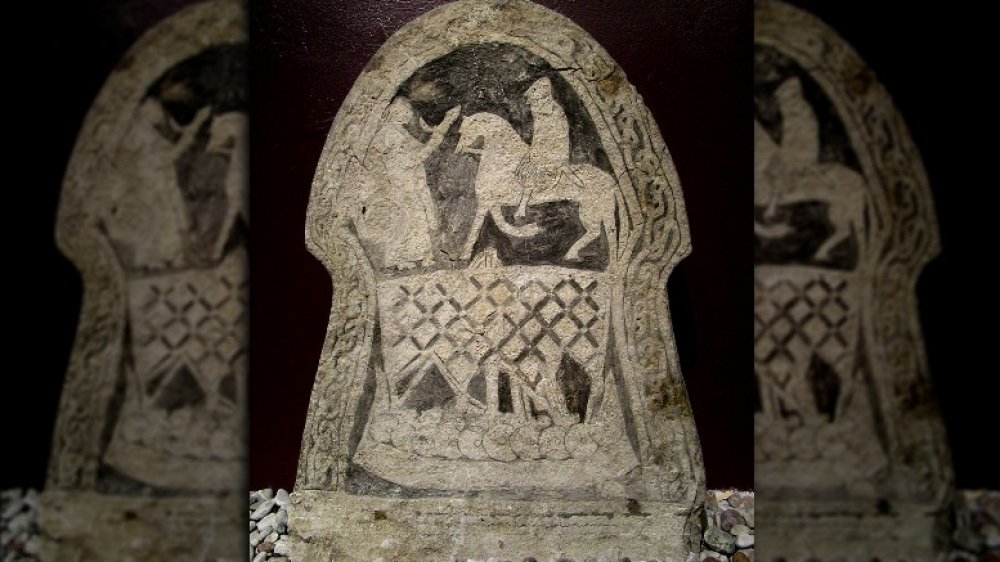

Erik couldn't muster much enthusiasm for the new beliefs, but his wife, Thjodhild, did. Soon enough, churches were sprouting up throughout the settlement. Archaeological evidence of pagan beliefs, reported in The Viking World, support the story of Erik's reluctance to abandon the old ways.

He led a fairly comfortable life in Greenland

Once settled, Erik picked a nicely situated place for his farm, which he called Brattahlid. According to The Age of the Vikings, it was near the head of Eriksfjord, about 60 miles away from the ocean and its harsh, changing weather. Brattahlid must have seemed a far cry from the dreary Drangar holding of Erik's first days in Iceland.

Erik's family set about changing to place soon after moving in. After her conversion to Christianity, his wife Thjodhild is said to have built a small chapel on the estate, says Journal of the North Atlantic, which may very well have been the first Christian church in the Americas. Other nearby structures include the main hall, a few outbuildings, and a cemetery with an estimated 144 graves.

At one farm building there, according to a 2005-2006 field report, archaeologists found stone walls about 1.5 meters, or nearly 5 feet, thick. A heavy layer of turf on the outside gave even more insulation. The floor inside was made out of flagstones, while the stalls were also made out of stone and, in one case, the shoulder bone of a whale. Clearly, Erik's family now had the means to create warm, sturdy buildings even for their farm animals.

He almost went further west, but a stumbling horse stopped him

Now well settled into his life as the head honcho of all Greenland, Eric the Red still had the drive to explore. The story told by Smithsonian Magazine says that a Norse trader named Thorfinn Karlsefni sailed west from Greenland and discovered Vinland, now assumed to be somewhere in modern-day Canada. Or, was it supposed to be Leif Erickson? The two main Norse sagas that tell the tale, The Saga of Erik the Red and The Saga of the Greenlanders, often collected together as The Vinland Sagas, don't always agree on the particular details.

In the version told by the Mariners Museum, Erik got the idea to travel to Vinland after hearing the story of a Norseman who was blown far off course and encountered the verdant land. With his son Leif now of adventuring age, the father-son duo prepared for a trip to explore these reports.

All looked well until Erik's horse stumbled on his way to the ship. He took this as a bad omen. Or, perhaps Erik took this as a sign that he was finally too old to fling himself into the wild unknown. Either way, Leif traveled on without his father and, says History, went on to become one of the first Europeans to visit North America.

The fate of Erik's people adds mystery to his story

From a storytelling standpoint, we love a mysterious disappearance. But, the Norse settlers of Greenland probably didn't enjoy the slow collapse of their settlements, which led to abandoned homesteads and empty landscapes. Scientists and historians have made some pretty good guesses, but we're still not sure why Erik's settlement faded away by the 1400s. For a while, the prevailing theory, as related in Collapse, was that the weather grew colder and more hostile to the agrarian lifestyle. The Norse were so committed to farming that they ignored the rich resources of the sea, refused collaboration with the Inuit, and therefore floundered.

That sounds pretty cut and dry, except more recent findings have upended the entire theory. More precise data and deeper investigation have shown that the Norse tried harder to adapt than we thought, says Science. Not only did the Greenland settlers focus more on trade to support themselves, but bones of sea animals made up a significant portion of garbage found in trash middens. Isotopic analysis of human remains from the time also shows growing levels of marine protein in the settlers' diet.

Perhaps the most frustrating thing is that we have very little testimony from the Greenland Norse themselves. While scientific tools can point us in the right direction, we may never know the true reason why Erik the Red's colony ultimately failed.

The tale of his life was written centuries later

The exact timing and circumstances of Erik the Red's death remain unclear. The Saga of the Greenlanders claims that he died of a "heavy sickness" that struck Brattahlid sometime around 1000 CE. Confusingly enough, The Saga of Erik the Red says that Erik actually survived the epidemic and was still around in the 11th century. If that's not enough to confound you, some legends like the one included in the Biography profile of Erik, say that he may have actually died of injuries sustained after he fell off a horse.

For all of the twists and turns in his story, we should at least be grateful that we know he existed at all. Without the literary drive of the Norse folk who lived in Iceland and Greenland, there may have never been a hint that this man existed.

That said, we should take those written sources with a grain of salt. The Saga of Erik the Red was probably written sometime in the 13th century, says Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History. That's two centuries after the man himself died, so it's not as if the author could interview anyone who was involved. At least the wealth of sources discussing Erik's life are enough to convince historians that he was a real person who had a definite impact on North American history.