Times Hamilton Lied To You About History

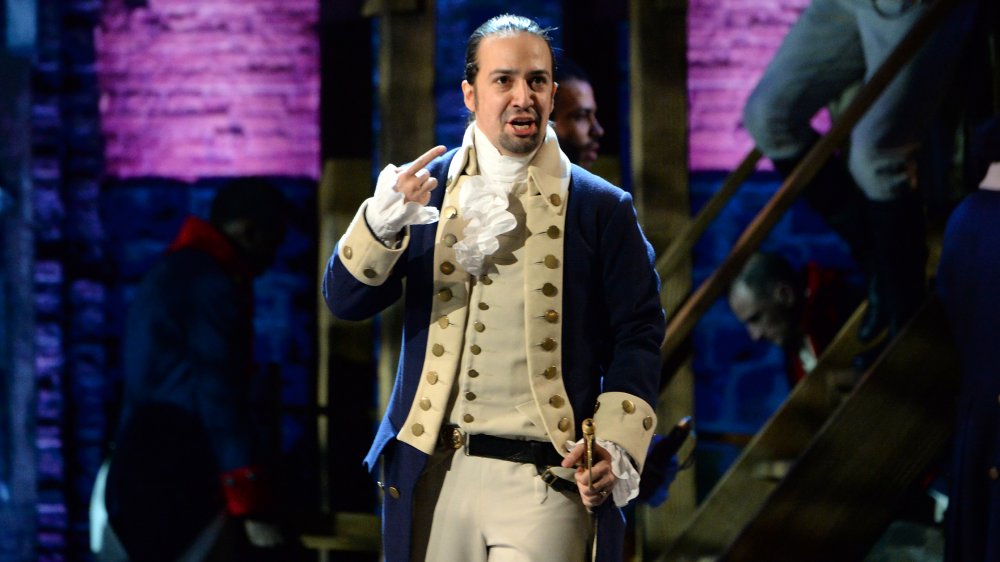

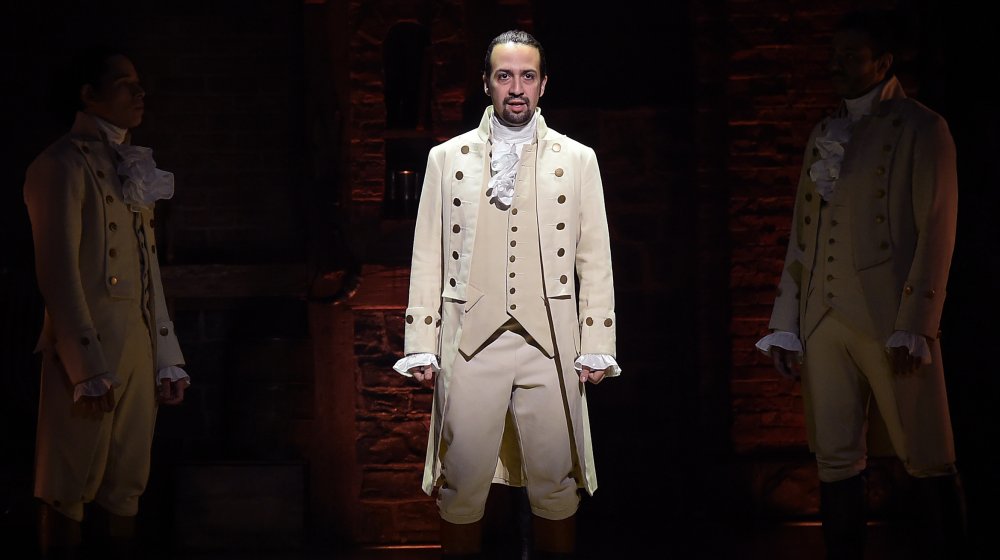

The musical Hamilton deserves every bit of its status as cultural phenomenon. Lin-Manuel Miranda took Ron Chernow's excellent work of history and biography and created something modern and fresh. With its color-blind casting, hip-hop-influenced songs, and exuberant costume design, the production is truly a watershed moment in the world of Broadway musicals.

Part of what makes Hamilton special is its density — as FiveThirtyEight notes, if its songs were sung like a normal musical (instead of the frenetic, speed-rap style it employs), it would take four to six hours to get through. The sheer amount of historical information and life story that Hamilton gets through has inspired many in the audience to learn more about Alexander Hamilton and the history of the country he helped found and shape.

That's ironic, since Hamilton plays fast and loose with historical fact. And while any play that imagines the Founding Fathers as a multiracial group engaged in rap battles is obviously not meant to be a history lesson (Vox calls it fan fiction, which feels right), many people might assume they're getting the whole story from Miranda's production, so it's important to note the times Hamilton lied to you about history. Here are a few examples of the creative liberties Miranda took in bringing the story to the stage.

Just about everyone in Hamilton owned slaves

There are a few glancing mentions of slavery in Hamilton, but in general, the subject is largely ignored. In fact, as Oprah Magazine notes, when the filmed performance debuted on Disney+, controversy erupted over this, with some arguing for the play to be "canceled" over these omissions.

The fact is, just about every major character in the musical — including our first president, George Washington — owned slaves. Attitudes varied a great deal, and many of these men spoke out against the institution and freed the slaves in their households (as Washington did toward the end of his life), but the simple fact remains that no one in the musical was free of the stain of slavery, including Hamilton himself.

Although Miranda writes Hamilton to emphasize his abolitionist beliefs, as Esquire reports, those beliefs were very mild. Hamilton never directly owned slaves, but he traded slaves, buying and selling them for others. And he married into the Schuyler family, which owned slaves. And although he belonged to at least one organization which aimed to abolish the slave trade, and Miranda's lyrics work hard to suggest otherwise, Hamilton actually did almost nothing in his otherwise very energetic career to end the practice. In fact, the only person who gets shade for his slave-owning is Thomas Jefferson, who Miranda uses as a villain in the story.

Alexander Hamilton didn't want democracy

For all his "immigrants, we get the job done" energy, Alexander Hamilton was not exactly a patron saint of democracy. Miranda's version of Hamilton emphasizes his immigrant status and presents him as a populist hero, a man who reaches the pinnacle of power and achievement through sheer talent. The musical's Hamilton has to fight elitists like Thomas Jefferson who view him as a nobody who doesn't deserve his place at the table at every turn.

Which is funny, because Hamilton himself was pretty elitist. In fact, he wouldn't recognize — or approve of — the nation as it exists today. As The New York Times reports, Hamilton was an "unabashed elitist" himself. He supported big banks and overwhelming federal power. As the National Constitution Center notes, Hamilton also proposed that the president and senators serve lifetime terms, in part because he didn't trust the people to make decisions for themselves.

In other words, in real life, Alexander Hamilton was almost the opposite of the character Miranda has created. He was someone who wanted to concentrate power in a very small group of people — a group he was part of, of course — and someone who didn't trust his fellow citizens to make decisions any more than he trusted rivals like Jefferson. Pretty much, the only opinion that Hamilton respected on these matters was his own.

Angelica Schuyler didn't give up Hamilton

Everyone enjoys a solid love story, and love triangles are even better. They generate tension and drama and make for some very emotional beats in the story. So it's not surprising that Miranda chose to highlight Hamilton's relationship with not one but two of the Schuylers — his eventual wife, Eliza, and her sister, Angelica (pictured above). In the musical, it's very clear that Angelica and Alexander fall in love, but she steps aside in favor of her sister because she has an obligation to marry a wealthy man. Their passionate but platonic relationship forms one of the core aspects of the story.

As Bustle points out, the reality was a lot less juicy. While it's very clear from their correspondence that Alexander and Angelica had a close and flirtatious friendship, there's no evidence that it went beyond that. Angelica also wasn't, as the play states, responsible for her family's fortunes because she had no brothers — she had brothers. And most importantly, Angelica was already married by the time she met Hamilton and had two children. (She would eventually have eight kids.)

And the marriage wasn't some stuffy arranged thing allowing us to imagine an unhappy Angelica pining for her Alexander. In fact, she eloped with John Barker Church against her family's wishes, hardly the act of a lady forced to social-climb due to a lack of brothers.

George Washington didn't dislike Aaron Burr

One of the smartest things Miranda does with his source material is put the relationship between Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton front and center. Their rivalry was very real and makes for an incredibly dramatic story in its own right. After all, how many of our frenemies actually wind up killing us in a pseudo-legal duel?

Miranda's a little hard on Burr, actually, overemphasizing his aversion to risk and making him seem like the sort of fussy person no one liked much. This is demonstrated by Burr's treatment at the hands of George Washington. The musical implies that Washington dislikes Burr and passes him over for promotion in favor of Hamilton due to a natural affinity he has for the younger man. This is made out to be a big part of why Burr is so angry with Hamilton.

But as author Arthur S. Leftkowitz makes clear, despite several rumors that circulated to make him look bad, Burr actually left Washington's service voluntarily because he had what he thought was a better job. His position on Washington's staff was a dull administrative post, and he thought working with Putnam would be a better gig, plain and simple. The decision had nothing to do with Hamilton.

Washington didn't beg Hamilton to return

The Broadway version of Alexander Hamilton is portrayed as a proud and ambitious man who was nevertheless selfless in his pursuit of America's independence. The character is frustrated throughout much of the first half of the story because he's never given an opportunity to show what he's truly capable of.

This dynamic is most plain in the relationship between Washington and Hamilton. After joining Washington's "family" (his closest military staff, who lived and worked together), Hamilton chafes because he wishes to have a field command, to lead soldiers. But when he and Washington have a falling-out, he leaves the future president's staff — until Washington, egged on by his French ally Lafayette, begs Hamilton to return to help him "turn the tide."

But as Ron Chernow writes, while Washington undoubtedly appreciated Hamilton's talents, he never begged the young man to return. It was Hamilton who pestered Washington, demanding his field command and eventually threatening to resign his commission if he didn't get it. This was a risk — Washington was the most influential and powerful man in the war, and Hamilton needed him if he was going to have the sort of career he desired. Irritating Washington even more than he already had would have been fatal to his prospects. There's no evidence that Washington would have bothered reaching out to Hamilton on his own. He was pretty busy fighting a revolution with people who were serving alongside him without demanding promotions.

Hamilton wasn't Washington's first choice for secretary of the Treasury

The musical implies that upon being elected our first president, George Washington's first order of business was tracking down Alexander Hamilton and getting him to agree to be secretary of the Treasury. It's also implied that this is a priority for Washington because he knows just how much of a genius Hamilton is.

It's undoubtedly true that Washington appreciated Hamilton's abilities despite his arrogance and tireless self-promotion. It's also undoubtedly true that Hamilton wasn't Washington's first choice for secretary of the Treasury. In fact, Washington expressed some doubt that the young man had the talents for the job.

As The National Constitution Center makes clear, Washington offered the job to Robert Morris (pictured above) first. Morris held a similar role during the revolutionary years and under the Articles of Confederation, so he was a natural choice — unlike Hamilton, who'd never had any real experience. But Morris wasn't interested in the job. He was familiar with Hamilton's prolific writing on the subject and knew they shared ideas about a central bank and a general economic vision for the young country. So Morris recommended Hamilton to Washington, and there's reason to believe that this recommendation was the only reason Washington even considered Hamilton.

Burr was the better man

To Lin-Manuel Miranda's credit, the complex nature of the real-life history and relationships between many of the Founding Fathers is reflected in his creation. These were passionate, articulate people who often had vastly different ideas concerning the shape and structure of this country. Things got heated.

If there's a villain in the musical, it's Thomas Jefferson, who waltzes in like a rock star, relentlessly opposes everything Hamilton tries to do, and then takes glee in trying to destroy him. But in many ways, Hamilton's antagonist in the play is Aaron Burr, his frenemy who tracks his career with mixed awe and rage — and who eventually kills him in a duel. That's all true enough — but it purposefully obscures Burr's achievements, making him look like a jealous wannabe who simply can't stand that an immigrant son of a prostitute outshines him.

As Time points out, the truth is quite different. Burr had his flaws, but his track record on slavery, freedom of the press, and women's rights is stronger than Hamilton's. History is written by the victors, and Burr's messy reputation in the modern age is in large part due to the efforts of Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson to discredit a man they saw as a threat to their own ambitions.

Eliza Hamilton didn't leave

Hamilton doesn't try to make Alexander Hamilton out to be perfect, and it highlights one of the biggest mistakes of his life — his extramarital affair with Maria Reynolds. This affair led to blackmail and humiliation and prompted Hamilton to publish a detailed account of his infidelity in order to prove his innocence of other charges. This, in turn, prompted his wife Elizabeth to leave him.

Except, she didn't. Ron Chernow makes it very clear in the musical's source material that Elizabeth Hamilton was certainly angry, but she didn't pack up the kids and leave her husband. In fact, her response was to go on the offensive. She railed against the people who had conspired to embarrass Alexander, who had forced what should have been a private matter between them into the open for political gain. And as The Washington Post points out, she held her head high and began fundraising for widows and orphans, refusing to cower or publicly denounce her husband.

The truth about Eliza Hamilton's feelings is also seen in how she lived her life after her husband's death. She worked tirelessly to preserve and protect his reputation and achievements — but when President James Monroe, the chief architect of Hamilton's humiliation, came to visit her years later, she refused to see him.

Hamilton's mother was not a prostitute

Part of the brilliance of Hamilton is its dense, richly imaginative lyrics, which manage to pack in a lot of facts, epic rhymes, and visuals in a fast-paced series of songs that are as smart as they are catchy. The first lines of the play, in fact, neatly lay out the overarching theme of Hamilton as the ultimate outsider and underdog: "How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by providence, impoverished, in squalor, Grow up to be a hero and a scholar?"

Describing Hamilton's mother, Rachel Faucette, as a "whore" fits the theme, but it's not true. As National Geographic explains, Faucette was a victim of the sexual politics of the time. Rachel married an older man, Johann Michael Lavien, and had one son with him. Unhappy, she tried to leave Lavien — but he had her thrown in jail for several months. When she got out, she ran, leaving behind her son and eventually meeting James Hamilton and having two sons with him, one of whom was Alexander.

When Lavien got around to seeking a divorce from Faucette, he savagely painted her as a loose woman who was no better than a prostitute, having affairs with many different men. The divorce was granted under Danish law, which meant that Faucette was forbidden to remarry and that her two sons with Hamilton (who had also left her by this time) were disinherited.

James Madison Gets Short Shrift

If all you know about James Madison, our fourth president, comes from the musical Hamilton, you think you know about three things: He was sick a lot, he helped write the Federalist Papers, and he was more or less Thomas Jefferson's flunky. Madison, white handkerchief fluttering, follows Jefferson around throughout Act 2 like an admiring puppy. You get the distinct impression Madison was just a member of Jefferson's entourage.

The truth is, Hamilton doesn't give Madison nearly enough credit. As The New York Times notes, Madison not only shaped much of the Constitution, but he was also one of the most talented politicians of his day. One reason he's not nearly as famous as his fellow Founding Fathers is simple: As author Kevin R.C. Gutzman makes clear, most of Madison's achievements were behind the scenes. He simply wasn't as loud or flashy as Jefferson and Hamilton.

The other reason Madison is often overlooked is that his presidency is easily seen as an extension of Jefferson's. After having such a profound influence on the formation and organization of the new country, Madison wasn't nearly as energetic when actually leading it. But the fact is that Madison was far from just Jefferson's sidekick. He was instrumental in framing our fundamental laws, was a fierce defender of religious liberty, and had just as much to do with how the United States of America turned out as anyone else in the play — and possibly more.

There weren't Ten Duel Commandments

Duels, understandably, play a big role in Hamilton. Although they were falling out of style and increasingly illegal by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, duels were still a thing among the elite when Hamilton was alive. Personal reputations were paramount, and there was no modern public relations machinery. When someone spread lies about you, you had to defend yourself — sometimes literally.

The song "Ten Duel Commandments" is one of the most memorable of the numbers in Hamilton, describing the rules surrounding an official duel between gentlemen. It takes some inspiration from the classic rap song "Ten Crack Commandments" by The Notorious B.I.G. and isn't a work of fantasy. As PBS confirms, there actually were codified rules for dueling: The Code Duello. But there weren't ten rules — there were 25.

The Code was put together at a meeting in Ireland in 1777 and was followed there, in England and Europe, and more or less in America. In typical American fashion, the code was considered more like a set of guidelines instead of actual rules, but the real reason Lin-Manuel Miranda made it ten rules instead of 25 is because of Biggie's classic — and the fact that no one wants a 15-minute song in the middle of a play.

Thomas Jefferson didn't get high with the French

Hamilton is a story, not history, and as such, it needs a few things history usually doesn't provide cleanly. Things like a clear hero — pretty obviously the guy the play's named after, natch — and a villain. While Aaron Burr truly did kill Alexander Hamilton, he's used more as a Greek chorus on Hamilton's life throughout the play, commenting on the man's achievements and setbacks. The real villain is Thomas Jefferson, who explodes into Act 2 like a ball of aristocratic energy to oppose Hamilton at every possible moment.

The truth about Jefferson is fudged a bit to make him more villainous. One of the most blatant lies about Jefferson in the play is contained in the line from "Cabinet Battle #1": "we almost died in a trench while you were off getting high with the French."

It's a great lyric, but as the Tampa Bay Times reports, Jefferson spent most of the war in America, not in France. He didn't go to France until 1784. Jefferson was no soldier, but he served his nascent country in ways that suited his talents — as an administrator and legislator. Jefferson didn't hide out in Europe while folks like Hamilton fought for freedom, and he didn't sail in like a rock star after the fighting was over, because he never actually left.