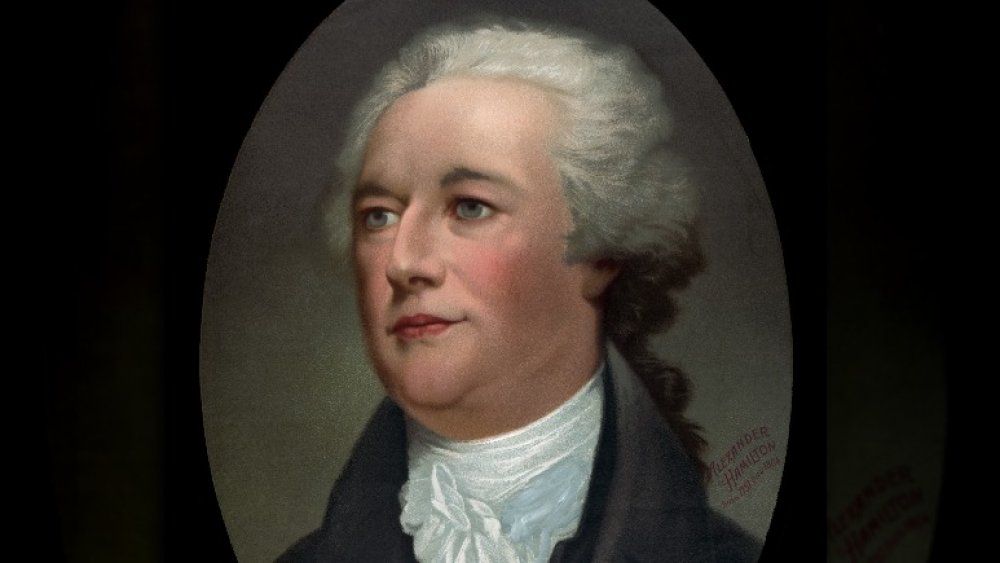

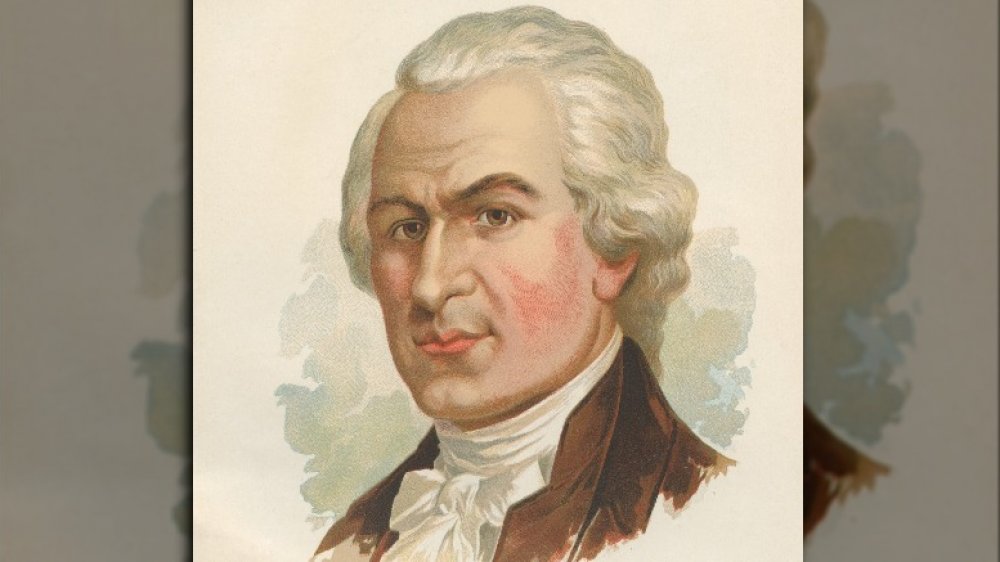

The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton has long been renowned as one of America's Founding Fathers, but he hasn't received quite as much attention in history as fellow founders. One reason Hamilton has had less recognition may be because many of his colleagues (and occasional political enemies) went on to serve as presidents of the United States, while Hamilton did not. Of course, the legacy of Alexander Hamilton has experienced an astounding revival thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda's hit musical, Hamilton.

The musical, which premiered in 2015, has become a cultural touchstone of our time, opening eyes and showing the powerful impact Hamilton had on the foundation of the United States. He was an enormously fascinating and complex figure. While Hamilton is an extraordinary musical that has brought history to the stage (and to Disney+), in many ways, it has only scratched the surface of Hamilton's real history. This is the tragic real-life story of Alexander Hamilton.

Alexander Hamilton's parents were never married

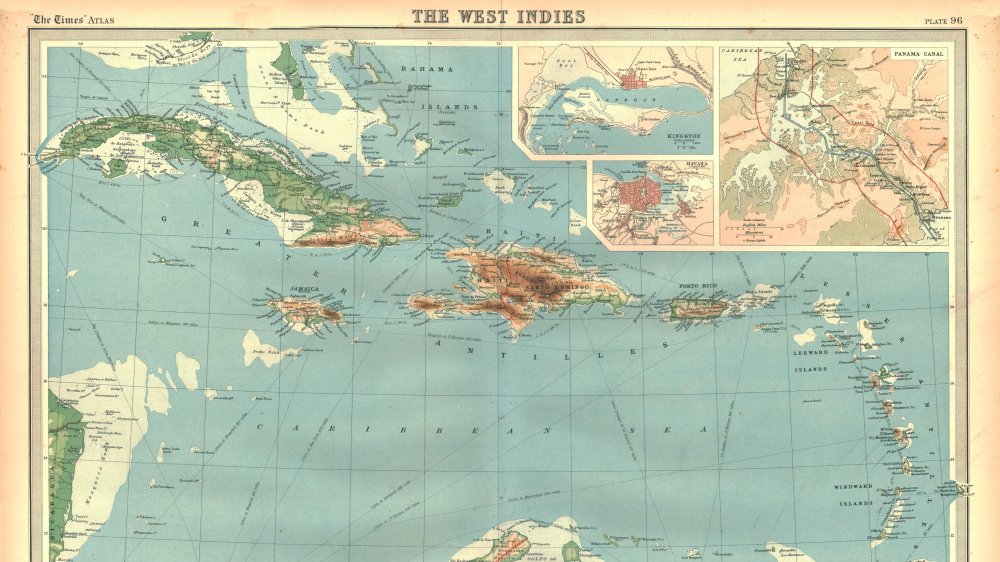

Alexander Hamilton had a rocky start to life. For starters, his parents were never married to each other, making Hamilton's birth "illegitimate." An illegitimate child in the 18th century was guaranteed to have a hard go of it, despite having no control over the circumstances. According to Biography, Hamilton's mother was Rachel Faucett Lavien, who came from a British and French Huguenot background, though she was brought up on the Danish-ruled Caribbean island of St. Croix. Rachel was already married to a much older merchant named James Lavien whom her family had pushed her to marry when she was still a teenager. The two had a son together named Peter. But Rachel's marriage to Lavien was a miserable one — Lavien brutally abused his young wife and squandered her entire inheritance from her father's death. Lavien even had Rachel imprisoned for several months (citing Danish law) on charges of adultery, though there is no record indicating these allegations were true.

As described by History Today, once Rachel was released from prison, she decided she couldn't go back to her awful husband and fled to St. Kitts. It was there that she met the Scottish trader James Hamilton with whom she resided and had two sons — James Hamilton Jr. and later Alexander. James Lavien later denounced his wife as a whore and divorced her, which may have been something of a relief for the much-maligned Rachel.

Alexander Hamilton wasn't allowed to attend school

Although a very intelligent child, neither the young Alexander nor his brother, James, were allowed to attend school when they were children. Since their parents were never legally married and the two boys were deemed illegitimate in the eyes of society, they were prohibited from any local school. Therefore, the boys were privately educated at home. Alexander in particular was especially bright. An avid reader, he pored over his father's collection of classical works and was very much self-taught. Through his devoted studying of his father's books, Alexander became highly literate and developed his writing skills early in life. It was thanks to this early study, Hamilton's hunger for knowledge, and his natural brilliance that would allow the young Alexander to secure his first job at an early age, and later to escape the Caribbean Islands for good.

Alexander Hamilton's childhood was plagued by instability

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, Alexander Hamilton never had a very stable childhood. His father, James Hamilton Sr., abandoned the family when his sons were still very young. According to Britannica, Rachel was left completely destitute and had to start working to provide for herself and her two boys. She managed to accomplish this by opening a provisions shop. Even the 11-year-old Alexander helped support the family by securing a position as a clerk in the counting-house of two New York merchants who had set up their practice on St. Croix.

In 1768, both Rachel and Alexander contracted yellow fever. Alexander eventually recovered, but Rachel died at the age of 38, leaving her sons orphaned. Alexander and his older brother were first given into the care of their older cousin, Peter Lytton. As described in the New York Times, Lytton was the Hamilton boy's legal guardian for one year until he was found to have committed suicide. The boys' uncle James Lytton, tried to settle the estate and care for the two boys but found himself hindered for legal reasons. James Lytton ultimately died a month after Peter's suicide. After that, the Hamilton boys were separated. Older brother James Hamilton became an apprentice to a local carpenter, and Alexander was adopted by a wealthy merchant while he continued to work at his job at the counting-house.

Alexander Hamilton's writing skills saved him

Alexander Hamilton could have had a much different life were it not for his extraordinary writing talents. According to Biography, from the age of 12, the young Alexander was already a talented poet and essayist who could write in both English and French. However, what sealed the deal for Alexander and propelled him to America was one single letter. In 1772, the West Indies was struck by a horrific hurricane that the teenage Alexander described in a letter he wanted to send to his father. He had the good fortune to first show the letter to his mentor, Presbyterian minister Hugh Knox. Knox was so impressed with Alexander's prolific writing skills that he proposed printing the letter in the local newspaper he edited. After reading the letter in the paper, other local businessmen were likewise amazed by Hamilton's talents and took up a collection to send Hamilton to King's College (later Columbia University) in New York. It was Hamilton's ticket off the Island of St. Croix and on to a greater destiny.

Hamilton's writing skills continued to serve him well throughout his life. As noted by Reader's Digest, he went on to write 51 of the 85 Federalist Papers and helped write George Washington's renowned Farewell Address. Hamilton also went on to found and publish the New York Evening Post which is still in print to this day as the New York Post.

Alexander Hamilton was technically an immigrant

While he certainly isn't an immigrant in the way we think of immigration today, Hamilton was technically an immigrant. He wasn't born in the colonies and he was never a British citizen, either. He was born and spent his entire childhood in the Caribbean — and the island where he grew up was under Danish rule. And, according to Reader's Digest, Hamilton's enemies never let him forget it. Even the Church of England denied Hamilton membership because of his parents' lack of a legal marriage. His non-native status plus his illegitimate birth gave Hamilton's political foes — and he had enough of them — plenty of fodder to work with whenever they wanted to denigrate and insult him. And quite a few of the Founding Fathers would count themselves as Hamilton's adversaries. John Adams himself referred to Hamilton as, "That bastard brat of a Scottish peddler!" James Monroe took a more direct approach and preferred to simply call Hamilton "a scoundrel."

Alexander Hamilton's best friend was killed

One of Hamilton's best friends was John Laurens whom he met while serving under George Washington during the Revolutionary War. According to Britannica, Laurens was the son of American statesman Henry Laurens, who served as president of the Continental Congress and was an early supporter of the patriot cause. John Laurens had a particularly crucial role in the war — he served as Washington's confidential aide and secretary. Laurens and Hamilton became very close friends while serving together. They both shared similar ideals and were passionate revolutionaries devoted to their cause against British rule. Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow speculates that Hamilton may have had a sort-of adolescent crush on Laurens.

As shown in the musical, Hamilton and Laurens' friendship was probably cemented when both testified against General Charles Lee after he bungled an attack on the British during the Battle of Monmouth. Lee was court-martialed. After insulting Laurens, Hamilton, and George Washington himself, Laurens challenged Lee to a duel. Lee was struck in the side by Laurens and honor was declared satisfied.

Laurens was sadly killed at the age of 27 at the Battle of the Combahee River in 1782 to Hamilton's eternal grief. Chernow said in an interview that Laurens' death dramatically affected Hamilton psychologically: "After the death of John Laurens, Hamilton shut off some compartment of his emotions and never reopened it."

Alexander Hamiton had serious health problems

Alexander Hamilton had an absolutely brilliant mind, but many don't realize he was actually plagued by numerous physical health issues — something that was never mentioned in Hamilton. While he did recover from yellow fever during his childhood in the Caribbean, Hamilton still suffered from residual side effects from the disease for the rest of his life. He had a recurring kidney ailment and a tropical malarial infection that would roll around almost every summer. After the Revolutionary War, Hamilton's health problems caught up with him and left him so ill that he was bedridden for two months. According to the Lehman Institute, while he was still serving as treasury secretary, he later fell victim to yellow fever once more after an epidemic hit Philadelphia in 1793. The disease ran rampant through the city and killed around 4,000 people. Luckily, Hamilton was treated and healed thanks to the medical attention of his childhood friend and adoptive brother, physician Edward Stevens.

Alexander Hamilton was involved in the nation's first love scandal

Sex scandals aren't new, and Alexander Hamilton has the honor of being the first person in recorded U.S. history to become entangled up in one. The musical Hamilton definitely covered the real-life Hamilton's affair with a woman named Maria Reynolds fairly accurately. As described in an article in Smithsonian Magazine, in the summer of 1791, the 23-year-old Maria approached Hamilton for help, claiming she needed money to get to New York and live with relatives after being abandoned by an abusive husband. At this point, Hamilton was secretary of the treasury and probably the second most powerful person in the United States. Hamilton was appropriately sympathetic to the beautiful Maria's plight and was eager to help. However, his sympathies soon became far less appropriate when the married Hamilton decided to have an affair with the young woman. Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow has referred to the Reynolds affair as "one of history's most mystifying cases of bad judgment."

However, according to History, Maria's husband– James Reynolds — discovered the affair and decided to take advantage. Reynolds blackmailed Hamilton for $1,000 (which would be around $25,000 in today's money) to keep quiet. Hamilton did pay the bribe in full, but Reynolds decided to stick around and encourage the relationship between Hamilton and Maria (who was now complicit in her husband's scheming) to continue. Unfortunately, a one-time pay-off wasn't satisfying Reynolds, and he kept coming back to request more "loans" until Hamilton ended the affair in the summer of 1792.

Alexander Hamilton was accused of financial scheming

Alexander Hamilton landed himself in hot water with the Maria Reynolds affair and subsequent blackmail. Hamilton does discuss the fallout, but the history is a little more complicated. According to Smithsonian, after the affair ended, James Reynolds was arrested on fraud charges and called on Hamilton for a favor. Hamilton declined. From his jail cell, Reynolds arranged a meeting with then-Congressman James Monroe after hinting that he had dirt on Hamilton. Reynolds claimed Hamilton was complicit in the financial scheme and forced Reynolds to share his wife — revealing Hamilton's letters to Maria. Monroe confronted Hamilton, who admitted he was not conducting crooked deals, but he was being blackmailed for the affair. Monroe agreed to keep this quiet once he saw that Hamilton's only offense was poor personal judgment. However, Monroe also sent Thomas Jefferson copies of Hamilton's letters to Maria.

The Reynolds affair wasn't publicly exposed until 1797 — after Hamilton stepped down as treasury secretary (he was never fired by John Adams). A Republican muckraker named James Callender obtained copies of the Reynolds letters and published a pamphlet accusing Hamilton of financial scheming and immoral conduct. Hamilton knew he couldn't deny the affair allegations, but he could defeat the scheming charges. Contrary to what happens in the musical, the affair accusation was already out there. Hamilton simply decided to save (some of) his reputation by publishing a pamphlet in which he fully detailed the affair and blackmail and successfully denied the corruption charges.

Alexander Hamilton's son was killed in a duel

Just like Hamilton himself would eventually die, Alexander Hamilton's eldest son, Philip, was killed in an ill-fated duel. In 1801, the 19-year-old Philip was at the theater with his friend, Richard Price, when they spotted a Republican lawyer named George Eacker. According to PBS, Eacker had made derogatory statements about Philip's father during a speech, claiming Hamilton wanted to overthrow the presidency and impose a monarchy. Philip and Price stormed Eacker's private box (they may have been drunk) and started hurling insults at him. The three took their argument to the lobby, but they failed to reach a resolution. Eacker called the two young men "scoundrels" (a high insult back in the day), which led to the call for a duel. Although Philip Hamilton seemingly led the charge to confront Eacker, it was actually Richard Price who initiated the duel challenge.

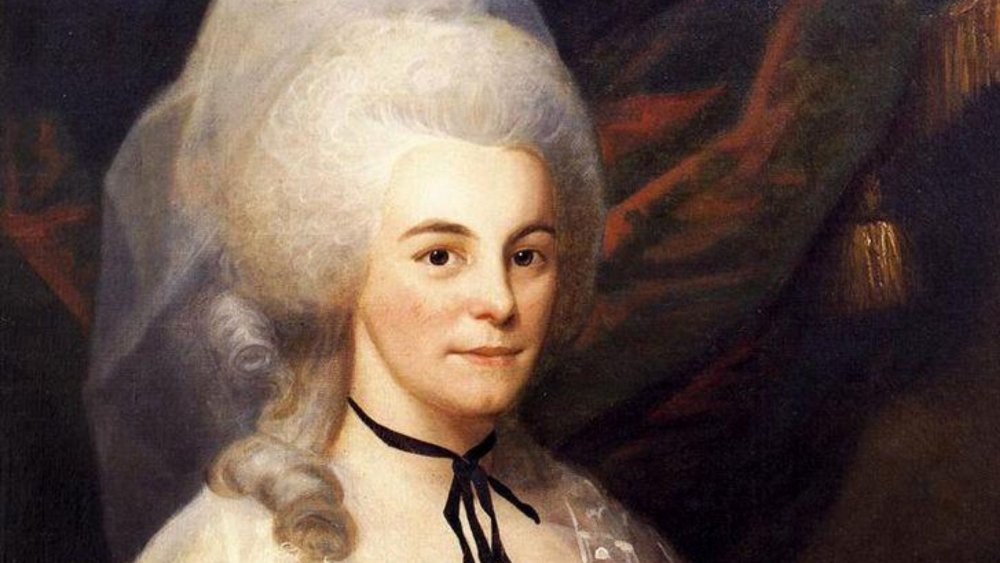

Eacker and Price dueled on November 22, and both walked away with no injuries after firing at each other. Philip was supposed to face Eacker on the 23. His father did not deter Philip from dueling but did suggest that Philip fire harmlessly to the sky to abort the duel. It is said that Philip did not shoot immediately, but Eacker took aim and fired. The bullet struck Philip, lodging in his left arm. Philip Hamilton died on November 24, 1801, devastating his mother and father.

Alexander Hamilton was killed by Aaron Burr

Despite the devastating loss of his son in a duel, that did not deter Hamilton from engaging in a duel of his own. As described by History, Hamilton and Aaron Burr were notorious political enemies — Hamilton was a Federalist, and Burr was a Democratic-Republican. Political enmity eventually turned to personal dislike, certainly in no small part by the fact that Burr defeated Hamilton's father-in-law in a U.S. Senate election. In 1800, when Burr tied with Thomas Jefferson for the presidency, Hamilton crusaded against Burr in Congress, lobbying for Jefferson instead. (Hamilton's efforts probably had little influence, but Jefferson was pronounced the winner.) Burr later ran for governor of New York in 1804 as an independent, and Hamilton deemed Burr untrustworthy, actively campaigned against him, and discouraged his fellow Federalists from voting for him. Burr lost the election to Republican Morgan Lewis.

According to PBS, because Hamilton so savagely attacked Burr's character, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel in the hopes of reviving his faltering political career. Hamilton was reluctant, but agreed, knowing that he risked his own career if he didn't. How the duel played out is up for debate (there's no proof that Hamilton actually fired to the sky), but we know Burr shot Hamilton in the stomach and the bullet lodged itself next to his spine. Hamilton died the next day. Burr was charged with two counts of murder and would never hold political office again.

Alexander Hamilton left his family with a mountain of debt

He might have been treasury secretary, but after Alexander Hamilton died he left his family with significant debt. Hamilton's political enemies certainly wanted people to believe that he was using his position to enhance his personal wealth, but quite the opposite was true. It could actually be said that Hamilton may have been too ethical. He refused his army pension for his military service — something he was undeniably entitled to accept. He could have made more money as a lawyer than as treasury secretary, but even when practicing law, Hamilton regularly undercharged his clients. Hamilton could have been quite a wealthy man, but he left behind a record that was absolutely free of any corruption.

However, his wife, Elizabeth, was stuck with a pile of debt. According to the National Archives, Elizabeth petitioned Congress for the military pension Hamilton had originally refused. Elizabeth didn't immediately receive the pension, but in 1816, Congress passed a bill that granted her five years' pay. Elizabeth Hamilton lived to be 97 and devoted the rest of her life to preserving her husband's legacy. She founded the Hamilton Free School, which provided education for children whose parents were unable to afford private schooling, and the city's first private orphanage, the Orphan Asylum Society, which would provide homes for hundreds of children. Elizabeth closely tied these organizations to her husband's memory as a reminder that Hamilton too was an orphan and thrived in America thanks to the help of generous benefactors.