The Truth About Fred Hampton's Tragic Death

In the predawn morning of of December 4, 1969, 14 police officers surrounded 2337 W. Monroe St, the Black Panther stronghold in Chicago. Inside, the Chicago Tribune wrote nearly forty years later, were 19 guns, more than 1,000 rounds of ammunition, and nine people sleeping, one of whom was Fred Hampton, the leader of the Black Panthers in Chicago. The raid about to be carried out was organized specifically to kill Fred Hampton.

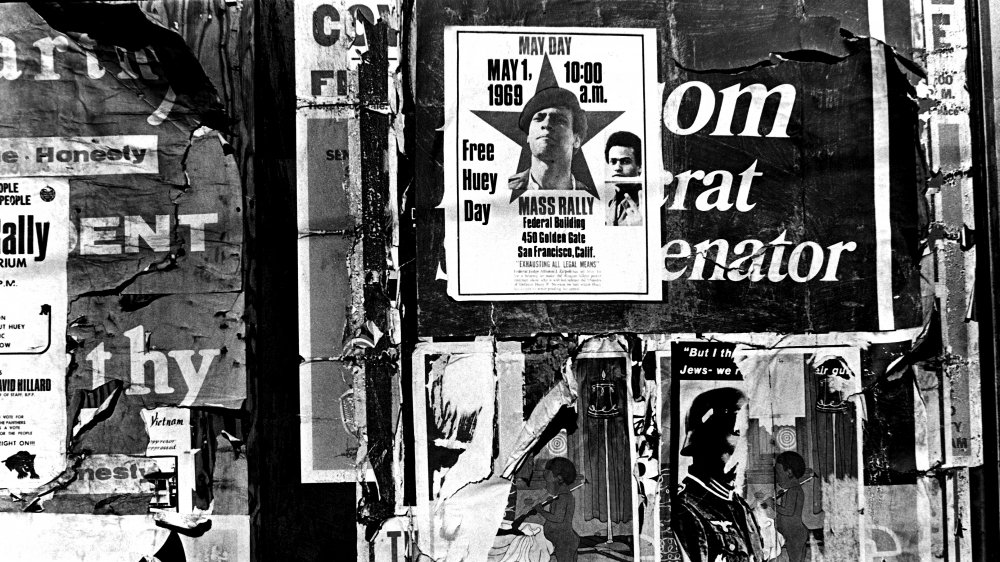

Hampton joined the Black Panthers in 1968. Until then, as summarized in the National Archives, he had been an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), leading their Youth Council of the organization's West Suburban Branch. Upon switching to the Black Panthers. Hampton quickly resumed a leadership role due to his gift for rhetoric and charisma. His lasting accomplishment was the Free Breakfast for School Children Program in Chicago, which fed impoverished children before school. To get a taste of his speaking, here is a section of him talking the Democracy Now plays from the documentary film The Murder of Fred Hampton: "You might murder a freedom fighter like Bobby Hutton, but you can't murder freedom fighting, and if you do, you'll come up with answers that don't answer, explanations that don't explain, you'll come up with conclusions that don't conclude, and you'll come up with people that you thought should be acting like pigs that's acting like people and moving on pigs. And that's what we've got to do."

Let's call it what is was: murder

Such a campaigner would be considered dangerous by many today. However, 1969 was during the Nixon presidency, the campaign of which was, as Forbes describes, "to vilify black Americans and justify raiding their homes unprovoked, incarcerating them in mass numbers, and even killing them under the pretense of 'protecting the public.'" While the police and carceral states today operate with such a logic, the racist emphasis Nixon deployed meant the FBI quickly deemed Hampton as a "radical threat."

So, the FBI approached William O'Neil, a convicted car thief. They hired him to infiltrate the Black Panthers for the price of making his charges go away. O'Neil did so, becoming the person in charge of Hampton's security. He fed the Feds a layout plan of the apartment and slipped Hampton a sleeping drug the night the raid was set to take place.

Before the clock struck five, Sergeant Daniel Groth knocked on the door. Nobody answered. The police started shooting and continued firing for the next seven minutes, firing off 82 to 99 shots. Fred Hampton was dead as was Mark Clark, a Black Panther leader from Pretoria. The seven survivors were put under arrest for attempted murder, owning weapons, and armed violence.

'This was nothing but a Northern lynching.'

In the aftermath of the raid, civil rights leaders and community members were outraged. As Jeffrey Haas, one of the attorneys representing the Hampton and Clarlk families, wrote in his book on the subject The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther, the general view was summed up by one elderly woman who saw the blood-soaked mattress: "This was nothing but a Northern lynching."

The surviving members were cleared of charges when evidence came in showing that compared to the 80 plus bullets fired into the building, only one had been fired in self-defense. Unsurprisingly, however, none of the officers who carried this out faced serious consequences, only, as the Chicago Tribune recalls, a reprimand from a grand jury which also criticized the surviving Black Panthers's lack of cooperation.

As vile as this crime was, one aspect of what makes Fred Hampton's case particularly special are the documentary films, the previously mentioned The Murder of Fred Hampton and Death of a Black Panther: The Fred Hampton Story, which was used as evidence in the trial. Firstly, it captures a portrait of Fred Hampton, whose words are prescient today. Moreover, they are some of — if not the — first videoed documentations of police violence against Black people, a genre that has surged in the smartphone age.