Famous Works Of Art With Messed Up Backstories

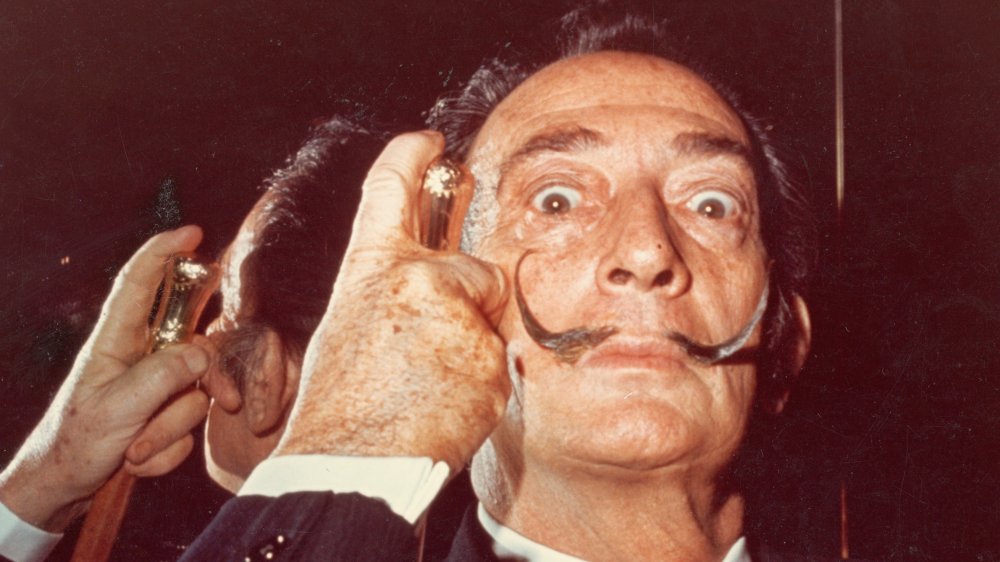

The French artist and writer Alfred Jarry declared: "The work of art is a stuffed crocodile." Then again, he lived on absinthe and ether and used to cycle around 19th century Paris with his face painted green. Salvador Dalí was similarly self-aware in his eccentricity, such as, when asked whether he used drugs, he claimed: "I don't do drugs. I am drugs!" according to The Dalí Universe. With quotes like these, it's no wonder the stereotype of the mad artist is so common.

But the world of art doesn't just attract unusual characters; it's also filled with strange and messed up stories. Many would argue that this is due to the "intensity" with which arty types lead their lives, mixing hedonism and violence, creativity and self-obsession, artistic vision with personal trauma. That means that more often than not, to know the background to a work of art, to put it in context with knowledge of the circumstances of its composition, means to pull even greater meaning from it. In other cases, such biographical information – about the work itself and the artist who made it – just makes for a damn good story.

And that's what we're here for, great stories attached to art that we perhaps know by sight, but not by its story. You'll never look at these works of art in quite the same way again.

Salvador Dali had serious mother issues

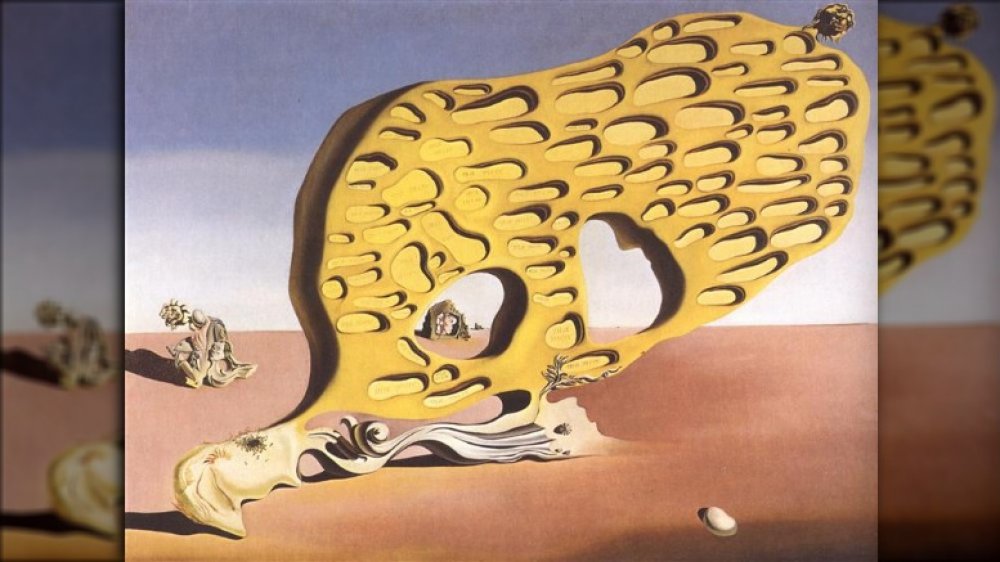

The Surrealist movement of which Salvador Dalí was at one time a central figure is considered to be a direct development of the Freudian thinking and psychoanalysis that dominated much of the art of the early twentieth century. Much Surrealist art is ambiguous, with artists recreating the subconscious images encountered in dreams and leaving others to decode what they might mean.

Dalí, however, seemed confident in self-analyzing the providence of the symbols that dominated much of his art – an aspect of his work that is reflected in his descriptive titles. Dalí's disturbing The Enigma of Desire, or My Mother, My Mother, My Mother, pictured above, is a case in point. Dalí seems to simultaneously ask us to analyze the meaning of the painting's 'enigma' in the first part, but then goes on to repeatedly give us the answer, which in turn guides our analysis. The viewer can't help seeing the image is about his mother – and to hammer the point home, the words "ma mere" are repeatedly written in many of the craters that cover the painting's central figure.

Dalí couldn't help thinking about himself in Freudian terms because of the highly Oedipal nature of his upbringing. The painter lost his mother at the age of 16, which was devastating for him, according to the Smithsonian. His loss was made particularly difficult in the years that followed, as Dalí had to deal with the fact that his father then went on to remarry his deceased wife's sister.

Tracey Emin's 'My Bed' was just too accurate

Tracey Emin rose to prominence within a generation of British artists that were used to controversy. As part of the "Young British Artists" collective that exhibited together in the early 1990s, Emin's My Bed was shown alongside such monumental and outrage-baiting work as Damien Hirst's The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, in which Hirst famously pickled a tiger shark in formaldehyde.

It is Emin's work, however, which seems to have attracted the most negative press, as reported in the Guardian. The My Bed installation was a recreation of a chaotic sleeping arrangement, with the bed surrounded by bottles of booze, old cigarette cartons, a pregnancy test, and menstrual stains. Objections ranged from those claiming that anyone could produce such a work, to those saying that the scene was too disgusting to display in public.

But the truth is, the bed is modeled closely on Emin's own – at least, the state her bed had been a few months previous to the art going on display. As The Telegraph notes, Emin had at one point spent days in such a pitiful state, consuming nothing but alcohol and cigarettes, before snapping out of it and getting the idea for the piece. My Bed is really a confessional sculpture, which also goes some way to explaining the strong reactions it provokes.

'The Charnel House' is graphically violent

Pablo Picasso's long career is punctuated with numerous famous anti-war pieces. The most famous is surely Guernica, a huge 1937 oil painting dealing with the bombing of the Spanish town that gives the piece its title by Nazi German and Fascist Italian troops. Picasso's famous Dove of Peace sketch is similarly iconic, having been used as the symbol of the First International Peace Conference in Paris in 1949, according to pablopicasso.org.

First exhibited in 1946, The Charnel House is no less overt in its anti-war sentiment, though perhaps its brutality is obscured on first viewing by the style. The Tate describes how the painting actually depicts a Spanish family that had been killed in their own kitchen – footage of which Picasso had seen in a short black-and-white documentary. Picasso's use of various values of gray, a style known as grisaille, is intended to replicate the unreal feeling of witnessing such violence on film. The fact that the image isn't immediately shocking is perhaps its intention; rather, we are made to feel growing unease as our eyes start to assemble a full image from the assorted shapes that are given to us in eerie monotone.

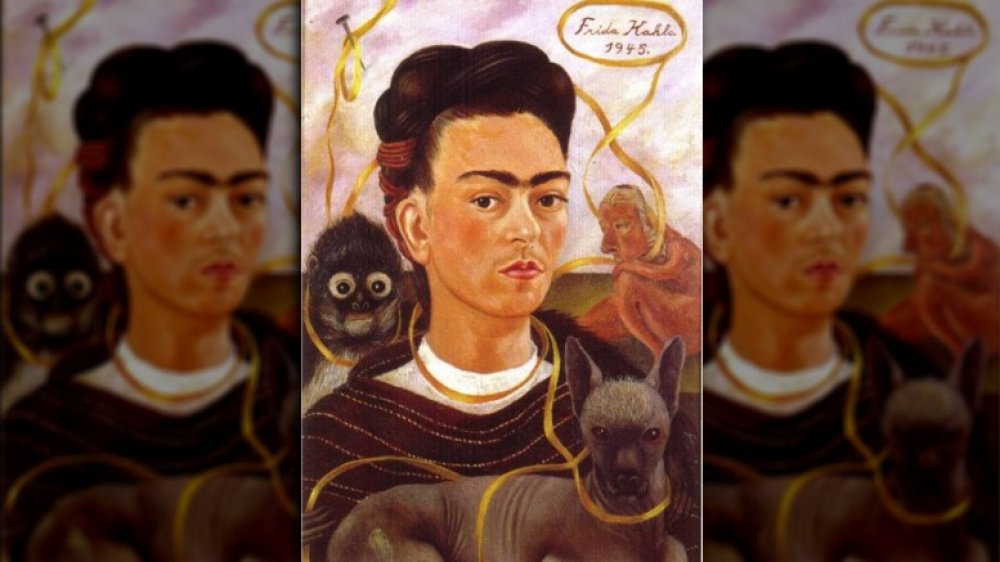

Frida Kahlo's 'Monkey' is a symbol of trauma

Frida Kahlo is most famous for her self-portraits, with her distinctively strong monobrow look, and she is now considered a glamorous artistic icon with her work adorning an array of merchandise, and her characteristic art can be found on everything from handbags to throw pillows and even sneakers. Despite her often being considered a symbol of strength for many women, her self-portraiture often shows her at her weakest and most vulnerable.

Kahlo had a tragic early life. According to Biography, she came down with polio at the age of six, which withered her right leg and left her with a pronounced limp in later life. Her recovery was to dominate her childhood and leave her isolated and alone. Later, as a politically-active teenager, she was critically injured in a horrific bus crash, in which she was impaled through her pelvis by one of the bus' iron handrails.

It is believed that it was these misfortunes that left Kahlo unable to have children, and many of her self-portraits in fact depict the artist in bed, surrounded by symbols of her ill health, and also of the miscarriages that she suffered as a result. Famous pieces such as Self-Portrait with Monkeys do not overtly carry such imagery. However, academics such as Museo Dolores Olmedo argue that images of Kahlo's favorite animals serve a melancholy purpose, representing the children that she was never able to have.

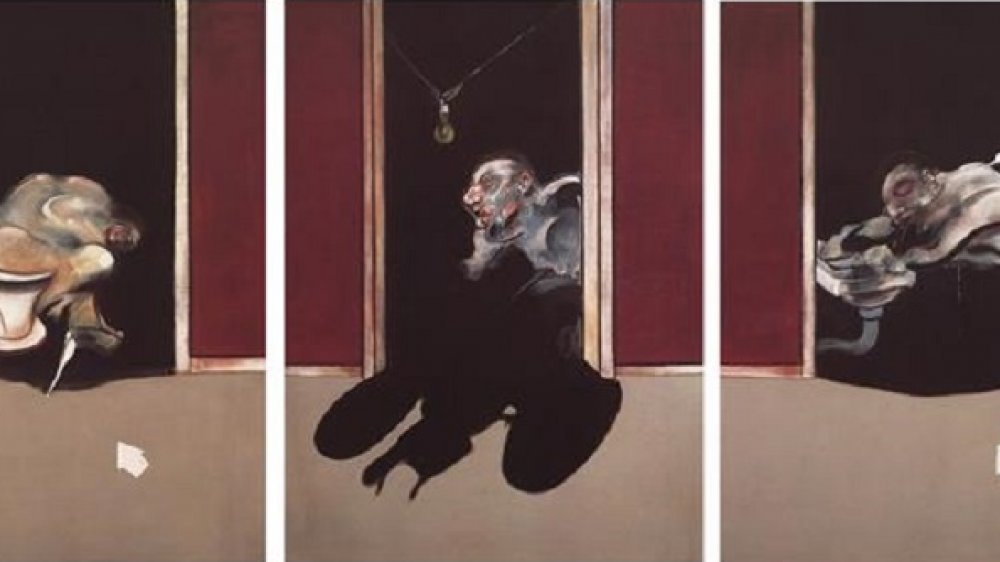

Francis Bacon's 'Black Triptychs' are also suicide scenes

Francis Bacon's work is most recognizable today for its strange, unworldly figures, in which the blurring of detail means we can't quite pin down the form of the object we are viewing in the painting. The reason for this in some of his most famous paintings, his Black Triptychs, has its root in Bacon's own traumatized reaction to what he was trying to depict.

In 1971, Bacon was in Paris, overseeing the opening of a glamorous retrospective of his work at the Grand Palais, and his long-term lover and muse, George Dyer, was in the city with him. The two had had a tumultuous relationship, made rockier by heavy drinking and drug use, according to Sotheby's. Two days before the exhibition opened, Dyer was found dead in Bacon's hotel room, after having taken an overdose of sleeping pills.

Bacon forced himself to continue with the exhibition as normal, but the death of Dyer never left him, and the artist painted him "obsessively" after his death, according to francis-bacon.com. The style that Bacon had mastered by the time of Dyer's suicide now came to take on a new significance – to visualize the horror of encountering such a death scene, and how the memory attempts to simultaneously revisit and distort the scene in question.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Andy Warhol hated Campbell's soup

Now for some light relief – it's true, the inventor of pop art actually hated the subject of his most famous creation. Messed up or what? Campbell's Soup Cans made Andy Warhol's name when the series of paintings were first shown in Los Angeles in 1962, and regardless of what you think of them in terms of art or ability – though the lack of ability on show is for many part of the point – their impact in the history of 20th Century art is incalculable.

Many sources, such as the Masterworks Fine Art Gallery, suggest that, as Warhol is known throughout his career to have painted what he loved – such as dollar bills and glamorous movie stars – that he must have had a great love for this particular brand of canned soup. Evidence for this is often given by the fact that Warhol claimed to have eaten the soup every day for 20 years.

But according to the biographer Tony Scherman, whose book, Pop, recreates the moment that Warhol and his friends came up with the idea, Warhol hated it. The fact was, his relatively poor upbringing meant that as a child, Warhol was forced to eat the same canned soup every day. In this context, the 32 varieties of Campbell's soup seem like something of a cruel joke at Warhol's own expense.

William Blake's 'Flea' is a demonic vision

The London-born artist, engraver, and poet William Blake is today revered as a visionary genius in the realms of both art and literature, but in his own lifetime (1757-1827) the son of a hosier was considered to be a madman by many of his contemporaries. According to poets.org, Blake claimed to have received mystical visions that began when he was just 4-years-old, when he saw God "put his head to the window" of his family home. Blake then saw angels that populated the neighboring trees, a vision that continued throughout his adolescence.

Such visionary experiences influenced his art strikingly, informing the "illuminated" works featuring heavenly forms for which he is most famous. However, the miniature The Ghost of a Flea represents something else within Blake's oeuvre – a challenge to his spiritual belief in the transcendence of human nature and imagination. According to the Tate Gallery, Blake's friend John Varley described how Blake claimed that creatures such as fleas are inhabited by the ghosts of bloodthirsty men. Blake's Christian beliefs were wildly unorthodox and thus allowed for his idiosyncratic adoption of reincarnation within his theological thought – it is true too that Blake considered conventional organized religion to be a form of devil worship, and that freedom and creativity were the key indicators of divinity and saintliness.

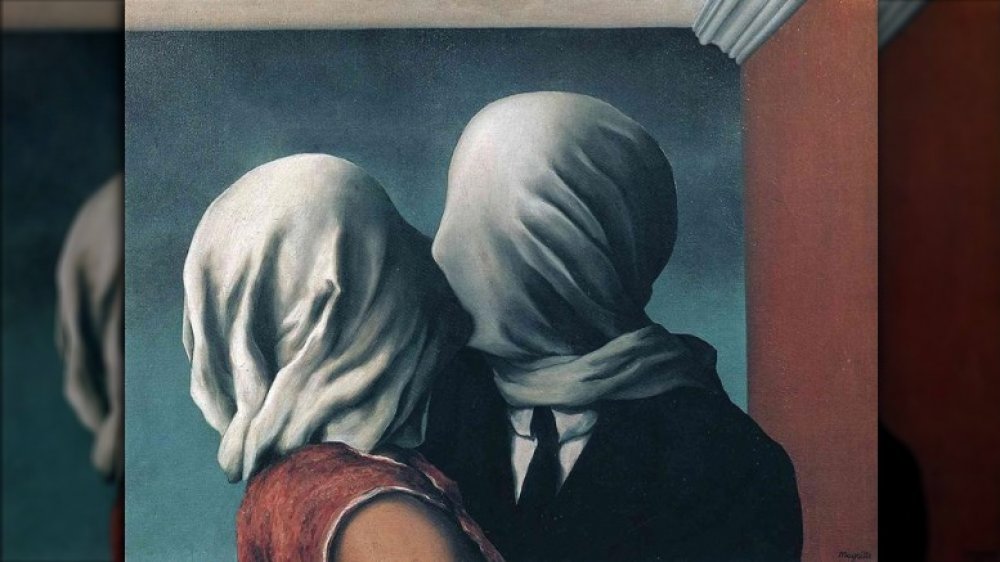

Rene Magritte's 'The Lovers' recalls his mother's suicide

The work of Rene Magritte is instantly familiar to most of us nowadays thanks to the great number of parodies and pastiches that exist in pop culture – especially of his paintings that feature anonymous men in bowler hats. The Lovers is perhaps not so globally iconic, but the images of faces obscured by light material have become something of a signature of the Belgian surrealist.

But the image is not derived, as with much surrealist art, from the artist's subconscious, but rather has its roots in a real, visceral, and woefully tragic experience from Magritte's youth. According to Artsy, when Magritte was 13, his mother committed suicide by jumping into the Sambre River. When her body was recovered, Magritte witnessed how the material of her nightgown had slipped up over her face, covering it, and creating the image that would recur throughout his work. It is also worth mentioning that Magritte's obsession with hats may have a similar psychological root – before her death, Magritte's mother used to work as a hat-maker.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Richard Dadd's 'The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke' was painted behind bars

Richard Dadd's baroque paintings – such The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke, his most famous work – are wonderfully intricate and dreamlike, and, if asked to describe the state of mind of the artist who created them, most people would assume that they were the creations of a mind that was totally at peace. That couldn't be farther from the truth.

The New Statesman describes how, in 1843, the British-born Dadd suffered a psychotic episode in which he brutally murdered his own father with a razor and a five-inch knife, before attempting to hide the body and escape to France. Once there, however, Dadd attempted another razor attack, this time on a fellow coach passenger, and was then arrested and brought back to Britain. In custody, Dadd claimed that he was ordered to undertake the attacks by the Egyptian sun god Osiris.

Dadd was imprisoned as a "criminal lunatic" for the rest of his life, dying in prison in 1886. According to the Tate, he worked on The Fairy Feller, in prison, for nine years.

Vincent van Gogh was trying to prove he wasn't insane

Many elements of the life and work of Vincent van Gogh have passed into popular culture since his death. In fact, some of the stranger elements of his biography – such as the fact Van Gogh amputated his own ear – are perhaps as famous to us nowadays as his paintings of sunflowers or his self-portraits. In fact, the incident and his work combine in Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, which depicts Van Gogh in the days after the event in question.

According to Khan Academy, Van Gogh had been living with his friend and collaborator, the artist Paul Gauguin, for more than two months, and together had been planning on opening a new studio together when their relationship deteriorated. Many say their falling out was the result of a love rivalry, with Van Gogh delivering his ear to the woman in question and telling her to "guard this object with your life." However, accounts of the exact sequence of events vary.

Whatever the case may be, Van Gogh ended up under psychological observation once his ear had been treated, with psychiatrists, concerned for his mental health, considering sending him to an asylum. The self-portrait, then, is Van Gogh's attempt to portray himself in a way that not only shows himself sane, but also that he has been following doctor's advice regarding his recovery, such as keeping and wrapping up warm in a coat and hat.

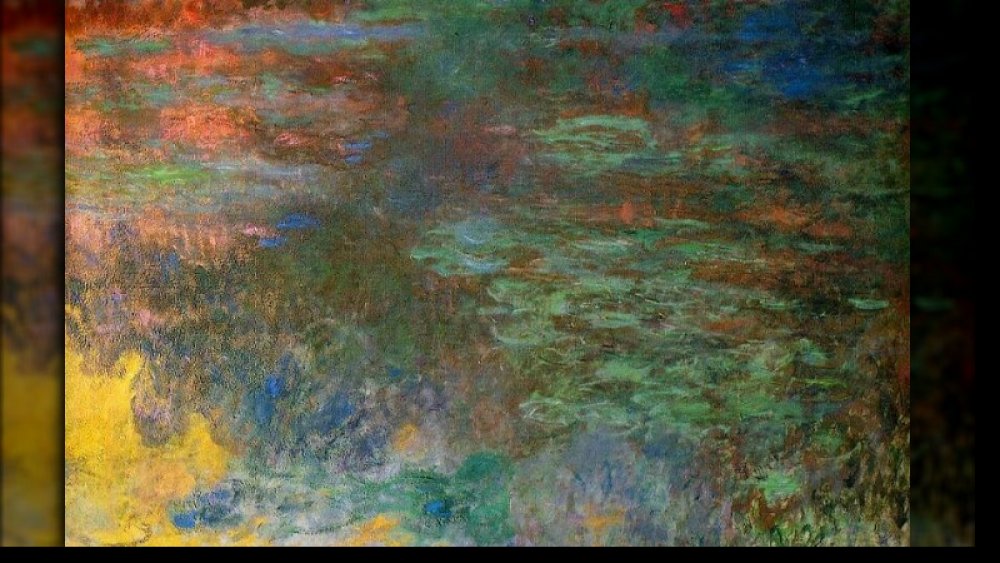

Could Monet see water lillies in unltraviolet?

Often mocked and sneered at by art aficionados when it was first displayed in the early 1920s, the work of Claude Monet is now celebrated for its innovative use of color and stylistic prowess. However, one theory is starting to gain some traction that means we may soon see the work of Monet in a whole new light.

In The British Journal of Medical Practice, Anna Greuner describes the effect that Monet's cataracts had on his work, and postulates how his symptoms acutely affected his painting; that rather than a concerted attempt at experimentation, his cataracts led to his adoption of an impressionistic style out of necessity. Monet was terrified of cataract surgery, refusing it on the grounds that similar surgeries undertaken by two other contemporary artists had been unsuccessful.

In 1923, however, Monet eventually agreed. According to the Guardian, this event may have had a great impact on the work that followed. The removal of the eye lens that such surgery involves potentially means that patients are then able to see in ultraviolet, which would cast a blue light over everything – just how Monet's Water Lilies looked immediately after his surgery.