Did Ian Fleming Steal James Bond?

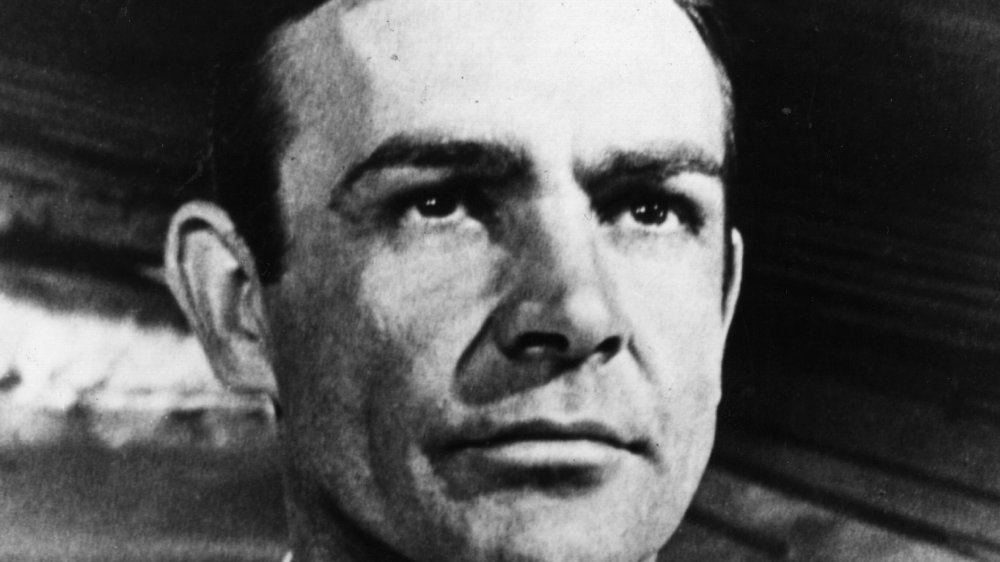

A quick primer for the cheap seats — Bond, James Bond, has been murdering, exploding, and seducing his way across the world of fictional international espionage for nigh on seven decades. Likes: killer gadgets, drinks that are shaken, and smoking three packs a day. Dislikes: communism, drinks that are stirred, and the rules. Between the spectacle, the camp, the quippy slaughter puns, and the earth-shattering kabooms, 007 has been demanding audience attention since the Cold War was still room temperature, pulling in around $20 billion as a franchise, according to International Business Times. And there's an argument to be made that all of that money came from that oldest and most noble of literary traditions: plagiarism.

At least that's what Rupert Allason thinks. Allason, also known by the pseudonym Nigel West, is a spy novelist and former member of Parliament (the governing body, not the George Clinton funk sensation.) In an interview with the BBC, he made a compelling case for the idea that MI6's most antibiotic resistant asset was stolen from author Phyllis Bottome.

Your word is my Bond

In 1946, Bottome published a new book, "The Life Line." It was the story of Mark Chalmers, a dark haired spy in his mid-30s, working under the head of British Intelligence, a man called B. Chalmers expresses interest in mountain sports, speaks French and German, appreciates the best epicurean offerings available to him, and is a hit with the ladies.

Seven years later, Ian Fleming debuted one James Bond in his novel "Casino Royale." Bond, a dark haired spy in his late 30s, works under the head of British Intelligence, a man called M. He also expresses an interest in mountain sports, speaks French and German, and really, you get where this is going.

Coincidence? There's an argument to be made, sure. Or there would be, if it weren't for the fact that Fleming and Bottome were well acquainted — she'd even vacationed at his villa in Jamaica in 1947 and, according to the BBC, encouraged a young Fleming to write his first short story in 1926.

The better part of a century after its release, Phyllis Bottome's "The Life Line" isn't even in print anymore, which is, if nothing else, a prime example of history giving someone the gold finger.