Lies Manhunt: Unabomber Told You

Modern industrial society certainly has its drawbacks. From mass surveillance to the military industrial complex to systemic racism, it's not all rainbows and kittens in our modern world. Of course, there are right ways and wrong ways to try to change things you don't like, and the Unabomber picked a very violent, very wrong way. From 1978 to 1995, a man the authorities have labeled "the Unabomber" (for "university" and "airline" bomber) sent 16 package bombs to targets across the United States, killing three people and injuring two dozen others. According to his manifesto, the Unabomber did this in an attempt to draw attention to the evils of industrial society — and to hopefully launch a large-scale uprising against the system.

Discovery's 2017 series Manhunt: Unabomber provides a fictionalized account of the years-long attempt to identify and arrest the Unabomber. The show is framed as a dramatic showdown between a shrewd FBI investigator, James "Fitz" Fitzgerald, and the elusive Unabomber himself, Theodore "Ted" Kaczynski. As the beginning of every episode states, Manhunt is "based on true events." However, while the show does get the basics correct, the writers of Manhunt alter many aspects of history to create a more exciting story. Let's dive into exactly how Manhunt: Unabomber broke away from reality.

James Fitzgerald never actually met Ted Kaczynski

Some of the most dramatic scenes in Manhunt: Unabomber come when James Fitzgerald meets face-to-face with the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski. Early in the show, we see a 1997 meeting between Fitz and Ted. Fitzgerald has been asked by the FBI to convince Kaczynski to plead guilty, but he's unsuccessful; instead, the two men discuss their critiques of modern society. It's not until later — after Kaczynski's failed attempt to overturn the search warrant of his cabin — that Fitzgerald convinces the Unabomber that a guilty plea is the only way to get his anti-technology ideas to live on.

These mental showdowns between two brilliant men — one fighting for law and order, the other for anarchy — are unquestionably entertaining to watch. Unfortunately, they're completely made up. Fitzgerald has never met face-to-face with Ted Kaczynski; the real Fitzgerald reports that the most intimate moment between the two men was some eye contact at Kaczynski's sentencing.

Fitzgerald did try to interview Ted Kaczynski back in 2007, but Kaczynski canceled the meeting at the last minute, asking a guard to tell Fitz that he was too busy. "You're in lockdown by yourself 23 hours a day seven days a week," Fitzgerald told WHYY. "However, he was too busy for me that day." Fitz is pretty confident that Ted isn't a huge fan of his.

Fitz didn't single-handedly bring down the Unabomber

After watching Manhunt: Unabomber, you'd probably think James Fitzgerald was the sole reason the Unabomber was brought to justice. The show depicts the FBI's UNABOM Task Force as a bumbling group of self-righteous veterans who spent 17 years with no concrete leads. Fitz is shown as the fresh blood with new ideas — ideas that are begrudgingly accepted by his old-school superiors when they're proven to work. The Unabomber's capture in 1996 is the direct result of the tireless efforts of Agent Fitzgerald, Manhunt: Unabomber implies.

This is a major deviation from reality. The real Fitzgerald told Bustle that the Fitz on the show was "a composite character" combining the contributions of many agents who worked on the case. Agent Fitzgerald did not personally figure out that the Unabomber must be an isolated, anti-technology academic, nor was he the primary advocate for publishing the Unabomber's manifesto.

Even so, James Fitzgerald wrote a fervent defense of his involvement in the Unabomber case after another retired FBI agent doubted the importance of his contributions. Fitzgerald argues that his analysis of the Unabomber's writing was critical to identifying Ted Kaczynski as the key suspect and obtaining a warrant to search his cabin.

Fitz didn't leave his wife for a woman he met on the Unabomber case

Even though James Fitzgerald was a consulting producer on Manhunt: Unabomber, the show doesn't always portray his character in the best light. In Manhunt, Fitz's obsession with the Unabomber case drives a wedge between himself and his wife, who ultimately decides to kick Fitz out of the house. But before his split with his wife was official, Fitzgerald is shown flirting with Natalie Rogers, a graduate student in linguistics who agreed to help Fitz analyze the Unabomber's unique writing style.

In reality, the stress of the Unabomber case did lead to a divorce between Fitzgerald and his wife. And, according to a conversation he had with the Press of Atlantic City in 2017, Fitzgerald is now in a committed relationship with a linguistics professor named Natalie Schilling. But the key difference between Manhunt: Unabomber and reality is that Schilling never actually worked on the Unabomber case, nor was she dating Fitzgerald at the time. While Manhunt's character Natalie Rogers is partly inspired by Natalie Schilling, it's also inspired by Roger Shuy, a Georgetown linguistics professor who played a key role in the case. Natalie (Schilling) + Roger (Shuy) = Natalie Rogers. The math checks out.

'Forensic linguistics' started long before the Unabomber case

Manhunt: Unabomber implies that "forensic linguistics" was a brand new field pioneered by James Fitzgerald and Natalie Rogers to crack the 17-year-old Unabomber case. Since the Unabomber took extreme care not to leave behind any traditional forensic evidence — like fingerprints or DNA samples — investigators had to rely on linguistic analysis in order to pin down a culprit. This approach was successful; after publishing the Unabomber's anti-technology manifesto, Ted Kaczynski's brother David contacted the FBI, saying the manifesto's writing style reminded him of letters that his brother had sent him. The FBI was able to confirm that the letters and manifesto had the same author, noticing similar linguistic choices — most notably, the seemingly-reversed proverb "Eat your cake and have it too."

Finding a culprit based on linguistic analysis was a majorly impressive feat in its own right, but Manhunt: Unabomber hammers in the excitement by telling viewers that "forensic linguistics" was completely unheard of before the Unabomber case, which is simply not true. The term "forensic linguistics" has been around since at least 1968, and Roger Shuy had been studying the field for quite some time before he helped find the Unabomber. Linguistic analysis has been used in a variety of cases throughout history, according to legal expert John Olsson, but the Unabomber investigation certainly seems to be the most high-profile example.

Manhunt: Unabomber's Tabby Milgrim didn't actually exist

While some docudramas create plenty of imaginary characters to present a more exciting narrative, Manhunt: Unabomber does not; the vast majority of the show's main characters are recreations of real people who were actually involved with the Unabomber case. One notable exception is FBI agent Tabby Milgrim. Agent Milgrim serves as James Fitzgerald's right-hand-woman throughout Manhunt: Unabomber. While most of the UNABOM Task Force rejects Fitz's plans, Milgrim encourages them, helping to lay the groundwork for the eventual capture of the Unabomber. In reward for her indispensable assistance, Fitz gets Tabby fired; she's removed from the task force after Fitz tells their bosses that Tabby secretly faxed him confidential documents.

The constant undermining of women's contributions is all too real. But Tabby Milgrim herself is a fabrication. According to Keisha Castle-Hughes, the actress who plays Tabby, the character is "a combination of a bunch of women that worked on the UNABOM task force." Milgrim may have been inspired by Candice DeLong, an FBI criminal profiler who helped lead the stakeout of Kaczynski's cabin. Or perhaps she's based on Kathy Puckett, an FBI Special Agent who used Kaczynski's writings to help identify his behavioral issues.

There was no 'mockingbird moment' that made the Unabomber abandon society

A few of the most memorable bits of dialogue in Manhunt: Unabomber come from one of the (fictional) interactions between Fitzgerald and Kaczynski. The men are discussing the exact moments they realized there was something deeply flawed about modern society. For Fitz, it was when he found himself sitting at a red light in the middle of the night — not a soul was around, and yet he still felt compelled to follow the rules that industrial society had imposed upon him. For Ted, it was the time in Chicago when he heard a mockingbird singing outside his window and realized it was imitating a car alarm.

Both these stories are quite beautiful in their simplicity. But then they should be — both are completely made up. The real Ted Kaczynski didn't abandon modern society because of some misguided mockingbird. But as it turns out, Kaczynski did have a "last straw" experience that made him commit to fighting the industrial system.

As Kaczynski told an interviewer, that moment occurred in 1983 on a trip to his favorite spot in the Montana wilderness, two days from his cabin. When he arrived, Kaczynski was dismayed to find that a road had been constructed right through the spot he loved. "From that point on, I decided that I would work on getting back at the system," Kaczynski told the interviewer. After that, Kaczynski's bombs became more destructive, and his first fatal explosion occurred in 1985.

Manhunt: Unabomber over-dramatized Ted Kaczynski's upbringing

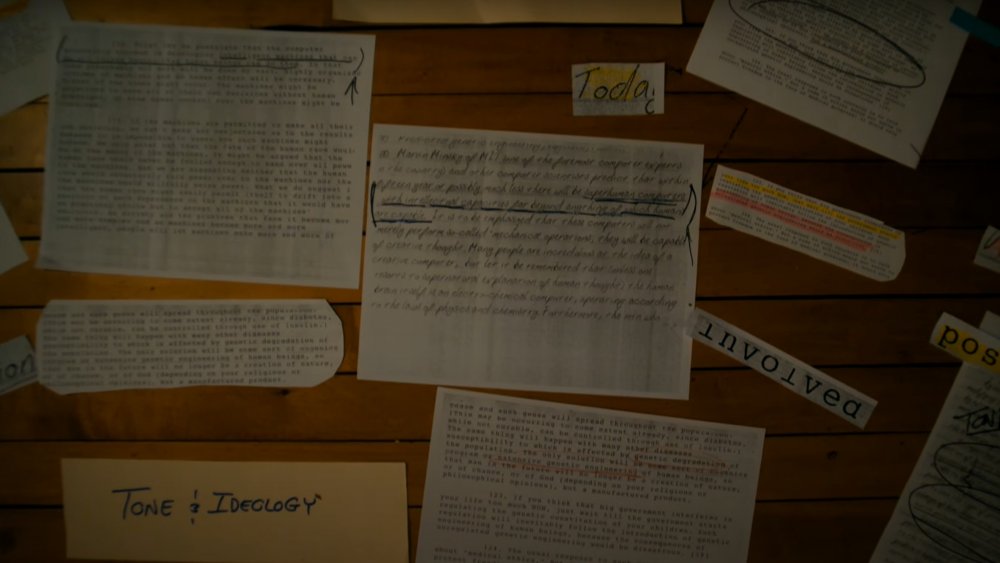

Episode 6 of Manhunt: Unabomber is the first to focus entirely on the Unabomber himself. The episode gives us a deeper look into Ted Kaczynski's past through a letter he's writing to his brother David, which serves as the background narration throughout the episode. The letter describes Ted's troubled childhood as a gifted child, his issues forming relationships with other people, and a devastating psychological experiment he endured while an undergraduate at Harvard.

However, the letter that frames this episode seems to be a fabrication written for the show, and the details it presents about Ted's childhood are heavily fictionalized. We know that Ted Kaczynski skipped two grades, but there's no evidence that he only had one close friend who later abandoned him. And while a friend of Kaczynski's did confirm his interest in explosives from a young age, there's no proof that Kaczynski sent tiny chemical bombs to anyone at his grade school.

And what about the dramatic Harvard experiment? Well, that part is actually true. The show provided a relatively faithful recreation of an experiment conducted by psychologist Henry Murray starting in 1959, as described by Psychology Today. However, Ted Kaczynski wrote a letter after Manhunt: Unabomber came out suggesting that the experiment was not nearly as torturous or damaging as the show would have you believe. Of course, it's possible it had more of an impact on him than he would want to admit.

The Montanans didn't actually like Ted Kaczynski that much

Manhunt: Unabomber's sixth episode also depicts one of Ted Kaczynski's semi-frequent voyages into Lincoln, Montana — the 1,100-person town situated close to the Unabomber's cabin. Kaczynski would often travel into Lincoln to get books from the local library and to buy essential supplies. Manhunt suggests that Ted had a friendly relationship with Lincoln's residents. He's shown exchanging polite greetings with the town's mailman, and he's particularly close with the librarian and her son; Kaczynski even accepts an invitation to the boy's birthday party, but becomes too uncomfortable to actually go inside.

In the real world, the people of Lincoln report having mixed feelings about Ted Kaczynski during his time living near the town. After Kaczynski was apprehended, Lincoln was flooded with members of the press, who pressured the locals to give their impressions of Ted. One woman described Kaczynski as a smelly "creeper" with no respect for women, saying he would sometimes peek through her windows. She would later discover that Kaczynski had stolen car parts from her property to use in his bombs. Similarly, Sherri Wood — Lincoln's real-life librarian — remembers Kaczynski telling her blonde jokes, then saying she should get her husband to explain them to her. (Wood said she actually found this rather charming, telling reporters that Ted had "a fantastic sense of humor.") On the whole, Lincoln seemed to view Ted as the weirdo in the woods, not some lovable outsider.

The Unabomber's package bombs didn't create big, fiery explosions

One of the very first scenes in Manhunt: Unabomber depicts a businessman being handed a mysterious package by his coworker. He takes the package to his office and proceeds to cut open the cardboard lid. As soon as he does, his office is destroyed in a large fireball. It's a dramatic way to begin the series, and the scene is based in reality — it's a recreation of the death of Gilbert Murray, a timber industry lobbyist who, in 1995, became the Unabomber's final victim. However, this scene exaggerates some key elements. In particular, it's highly unlikely that Murray would have been killed by the big, Hollywood-style explosion you see at the beginning of Manhunt: Unabomber.

Ted Kaczynski was skilled at chemistry, and his bombs did get more complex over time. Regardless, he was no explosives expert and was restricted to working with common materials. As a result, the destructive power of Kaczynski's bombs came primarily from the shrapnel they enclosed. The Washington Post described one of the Unabomber's victims as being maimed by "shrapnel wounds and powder burns." Some of Kaczynski's later victims lost fingers, and others were partially blinded; a total of three people were killed.

The final bomb found under Ted's bed was actually kept as crucial evidence

In the penultimate episode of Manhunt: Unabomber, viewers finally get to see FBI investigators raid the Unabomber's cabin, arresting the man who had spent 17 years mailing bombs to targets across the country. After Kaczynski is in custody, Manhunt shows investigators surveying his cabin via a remote-controlled robotic vehicle. Besides finding a variety of bomb-making equipment in the cabin, they also find a fully made bomb under Kaczynski's bed, which they proceed to detonate at a safe distance.

In reality, while a complete bomb was found under Kaczynski's bed, it wasn't immediately discarded. In fact, the FBI took special precautions to ensure that the bomb wouldn't detonate so they could take it apart and compare it to the bombs known to be constructed by the Unabomber. A Popular Science article from 1998 tells the story of the three bomb disposal experts tasked with disassembling the explosive package. By carefully studying the Unabomber's notes and by using the best technology 1996 had to offer, the experts successfully diffused and dismantled the bomb, though they did have some close calls. It's a dramatic tale, and it's surprising that Manhunt: Unabomber decided to leave it out.

Manhunt: Unabomber makes up a few answers

As of 2020, there are a number of questions about the Unabomber case that continue to stump the experts. One unresolved dilemma is the origin of the words "Call Nathan R wed 7 pm" that were faintly imprinted on the envelope of one of the Unabomber's letters. This "Nathan R" message was considered a major lead in the Unabomber case. According to the Washington Post, it led investigators to contact thousands of Nathan Rs across the country. But the hunt was a wild goose chase. The "Nathan R" message was completely irrelevant to the case, and its meaning remains unknown. To resolve this, Manhunt: Unabomber explains that the imprint was left behind by a mailroom intern at the New York Times who had a habit of writing Post-it-Note reminders to himself. Believable? Sure! The truth? Probably not.

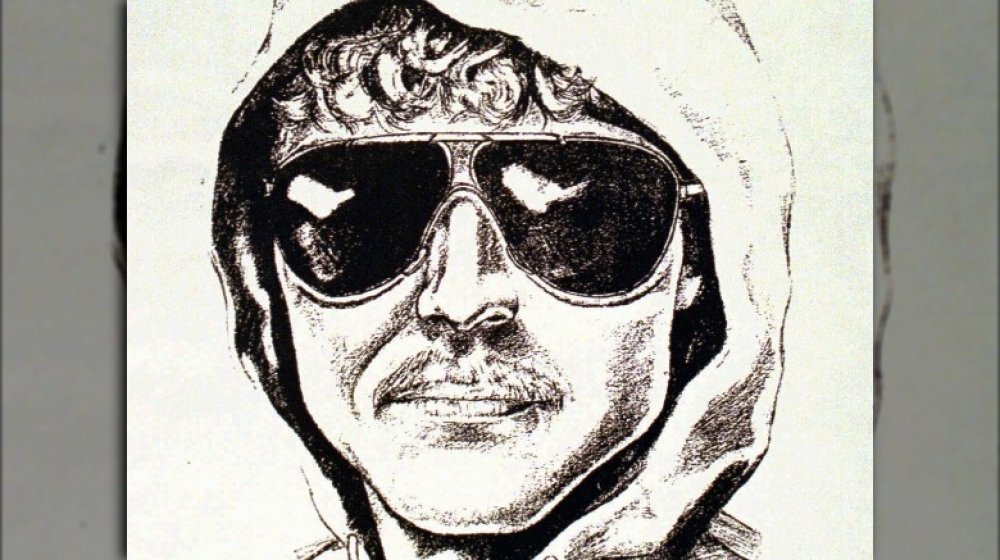

Another unanswered question is why the Unabomber sketch doesn't much resemble the real Ted Kaczynski. The image was based on the testimony of a Utah woman who briefly saw Kaczynski leaving a bomb outside a computer shop in 1987. But, as reported in the Chicago Tribune, the now-famous sketch was drawn "nearly eight years later" by forensic artist Jeanne Boylan. Manhunt: Unabomber suggests that during her meeting with Boylan, the witness was subconsciously describing another sketch artist she met with for many hours in 1987, and not the serial bomber whom she only glimpsed. While intriguing, this explanation appears to be yet another made-up story.

Ted's lawyers didn't actually sabotage him on the FBI warrant

In the final episode of Manhunt: Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski is dangerously close to being set free. (Most viewers probably know that won't happen, but it's more fun when you play along.) Ted tells his lawyers to argue that the FBI's search warrant was obtained without sufficient justification. If a judge agrees, then all the evidence collected from Kaczynski's cabin must be thrown out, leaving almost nothing to tie him to the Unabomber's crimes.

It's a brilliant legal play, and Manhunt: Unabomber almost makes you want to see it succeed. But when the warrant hearing comes, Kaczynski's lawyers ask to meet with the judge privately; when they return, the judge immediately denies the motion to reject the warrant. The implication is that Kaczynski's lawyers sabotaged the motion so they could move forward with their own preferred plan-of-action: convincing a jury that Ted Kaczynski is insane.

It's a spicy final twist, but one that's patently false. According to a New York Times article from June 1997, Kaczynski's lawyers really did try their best to convince a judge that the FBI's warrant was wrongfully obtained, but the judge disagreed, saying there was "substantial justification for the search." It was only after this legal failure that Kaczynski's lawyers turned to an insanity defense — which Kaczynski vehemently opposed, deciding to plead guilty instead. Now, Kaczynski is serving eight life sentences in maximum-security prison, where he continues to send and receive many letters (but no packages).