The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Jesse Owens

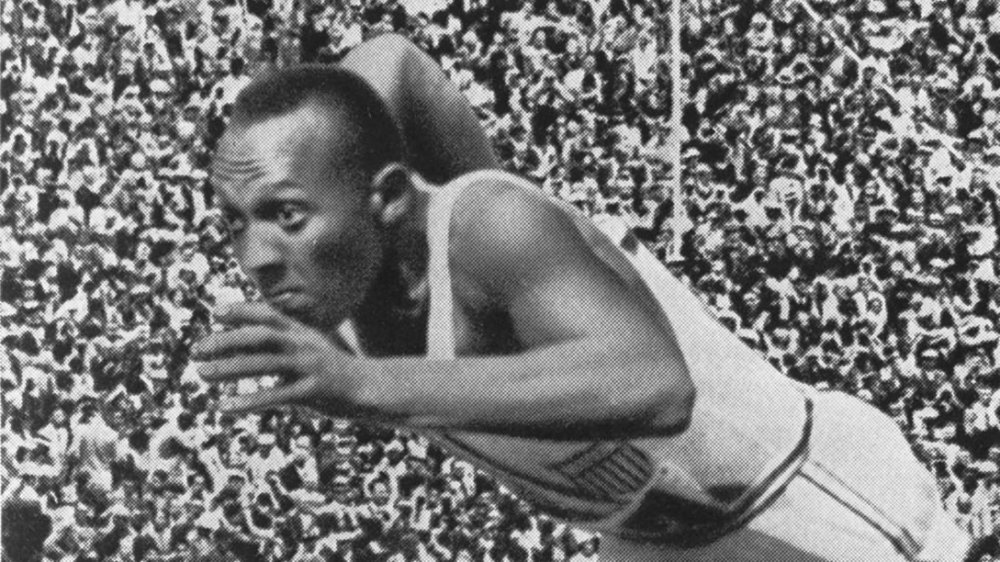

The story you know about Jesse Owens probably starts and ends with him winning four gold medals in the 1936 Berlin Olympics — also called the Nazi Olympics. You probably heard that Hitler was so furious at watching a Black American humiliate Germany's best white athletes over and over again that he stormed off and refused to shake Owens' hand. You might also have seen the 2016 biopic Race, starring Stephan James as Owens.

However, Owens and his life story are so much more than those seven days in 1936. He traveled from the cotton fields of Alabama to industrial Cleveland, and later to Michigan, London, Chicago, India, the Philippines, and finally to Tucson, AZ. He was a college student, an elevator operator, a waiter, a public speaker, a record-breaking athlete, and a goodwill ambassador. He's been abused, neglected, ignored, forgotten, and celebrated. This is the crazy real-life story of Jesse Owens, the man who turned a once-in-a-generation gift into Olympic gold four times over.

Jesse Owens was the grandson of enslaved people

Jesse Owens was born James Cleveland Owens on September 12, 1913, to Henry Cleveland and Mary Emma Owens, in Oakville, AL. James' grandparents had been enslaved and his parents were sharecroppers: they rented a small plot of land from a white landholder, in exchange for a share of their crops.

Jesse — known as J.C. — was the youngest of Henry and Emma's 10 children, all of whom worked alongside their parents in the cotton fields. Jesse was a frail kid. He suffered from bronchitis and pneumonia, but his parents couldn't afford a doctor. Time Magazine reported that when he was five, Emma had to cut a tumor out of his chest using a knife sterilized over a flame.

Despite these difficulties, Jesse maintained that his childhood was happy, according to the Telegraph. His family had fun together, and his parents made sure they always had enough food. When he was around nine, the family moved to Cleveland, OH, in search of more employment opportunities and an escape from the racist violence common in Alabama — not that the North was a paradise for Black people. It was in Cleveland that Jesse got his famous nickname: one of his teachers couldn't understand his Southern pronunciation of "J.C." and called him Jesse, a name that stuck.

Jesse Owens started running competitively in junior high

In spite of his poor health, Jesse Owens always loved running. "I wasn't very good at it, but I loved it because it was something you could do all by yourself, all under your own power," he wrote in his autobiography. When he got to Fairmont Junior High School, Owens came to the attention of Charles Riley, the school's track coach, who became his first mentor and an additional father figure: Owens called him Pop. The pair trained early in the mornings since Owens worked numerous after-school jobs to help support his family, including delivering groceries, loading freight cars, and repairing shoes, according to the Telegraph.

As well as sprinting, Owens broke the junior high world records in high jump and long jump. When Owens moved on to East Technical High School at 17, Riley went too, working as an assistant to the coach. At the National Interscholastic Championships in his senior year of high school, Owens tied the 100-yard world record and set a new world record for the 220-yard dash. He tried out for the 1932 Olympic team but didn't make it.

Meanwhile, his home life had hit a rough patch. His father and brothers were out of his work, and his girlfriend Ruth gave birth to their daughter Gloria Shirley on August 8, 1932, when she was 16 and Owens was 18. Ruth and Jesse married in 1935, and stayed together until his death in 1980.

Jesse Owens was the first Black athletic captain at Ohio State

Jesse Owens' record-breaking high school career earned him offers from numerous colleges. Most notably from an athletic standpoint were the University of Michigan and Ohio State University, both members of the prestigious Big Ten. Neither offered Owens a full ride, but Ohio State was willing to let him work various part-time jobs to help fund his degree. The Telegraph later reported that he worked as a waiter, elevator operator, and a gas station attendant, all while training and studying.

At Ohio State, Owens trained under coach Larry Snyder — one of the few college coaches who included Black athletes on his teams. Owens was named the first Black captain of the school's athletic team, and nicknamed the Buckeye Bullet.

Despite his star status on the team, Owens still faced racism within college and on the road. He was barred from living in the men's dorm because of his race, and instead lived in a boarding house with the school's other Black students. When the track team traveled, Owens and his fellow Black athletes weren't allowed into whites-only hotels with their teammates, and had to take food from whites-only restaurants to their bus, or find somewhere that served Black people. Even the showers at the school were segregated.

In 2001, Ohio State named the 10,000-seat Jesse Owens Memorial Stadium after their famous alumnus: it houses the university's track teams, among other sports.

Jesse Owens' personal career highlight was not the 1936 Olympics

It doesn't get any better than winning four Olympic gold medals and shattering the racist ideologies of a dictator and his cronies, right? It did for Jesse Owens. In his autobiography I Have Changed, Owens wrote that his finest day was May 25, 1935. Specifically, a 45-minute window in which he broke three world records at the Big Ten Track and Field Championships, all with a back injury.

As Sports Illustrated reported, at 3:15 pm, Owens equaled the world record for the 100-yard dash, at 9.4 seconds. (More than half of the timers actually showed him at 9.3 seconds, but the slowest time is taken.) To save his back, Owens only made one attempt at the long jump — and he broke the world record by more than six inches. Nine minutes later, he broke the world record for the 220-yard dash, coming in at 20.3 seconds, 0.3 seconds faster than the previous record. And 26 minutes after that, he ran the 220-yard low hurdles (they're 2.5 feet tall) in 22.6 seconds, the first runner to break 23 seconds.

The pre-Olympic year was a good one overall for Owens' athletics career. In 1935, he competed in 42 events — including four at the NCAA Championships, two at the American Athletic Union (AAU) Championships, and three at the Olympic trials — and won them all.

Jesse Owens won four gold medals and showed up the Nazis

The reason Jesse Owens' fame isn't limited to college sports is, of course, because of his success at the 1936 Olympics. These weren't just any Olympics. They were held in Berlin, Germany, then the center of Nazi power. The city had been awarded the Games in 1931, but in 1933, fascist Adolf Hitler had maneuvered his way into power, introducing racist, anti-Semitic and homophobic laws, and building up Germany's army. There had been debate over the US boycotting the Olympics to protest the Nazis' human rights abuses, and some American Jewish athletes did. But History says 312 American athletes traveled to represent the US, including Owens.

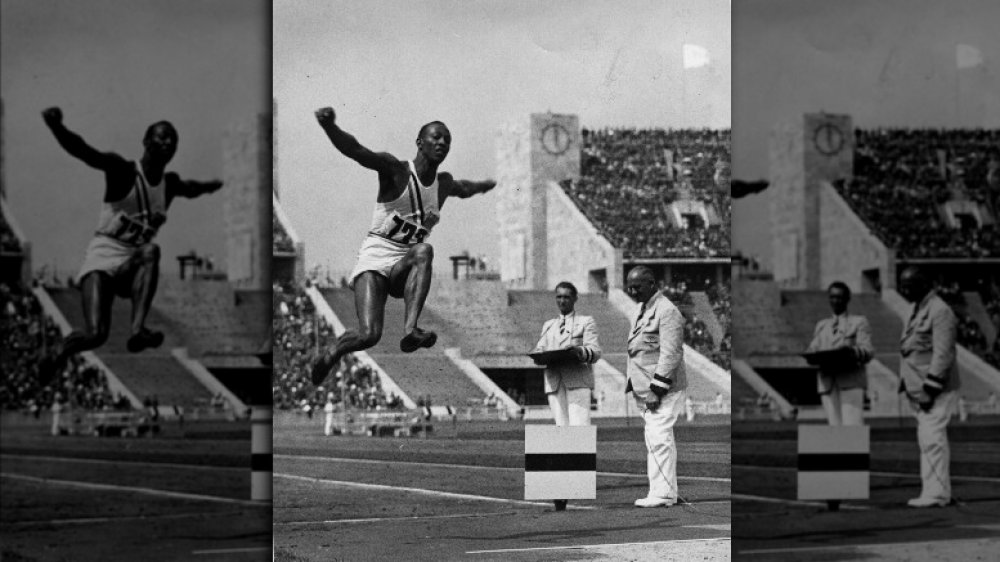

Germany ultimately won the most medals — they had the most athletes — but the American team dominated in track and field, and Owens was the star. He equaled the 100m world record, and set records in the 200m race and long jump: his distance stood until 1960. He won his fourth gold medal as part of the 100m relay team, setting a record that stood for 20 years alongside his teammates.

Hitler had hoped to use the Olympics to showcase his crackpot theories of white supremacy. Owens and his fellow Black athletes were living, winning proof that he was wrong. In his autobiography I Have Changed, Owens wrote of his Olympics experience: "It was as if I'd destroyed Hitler and his Aryan-supremacy, anti-Negro, anti-Jew viciousness."

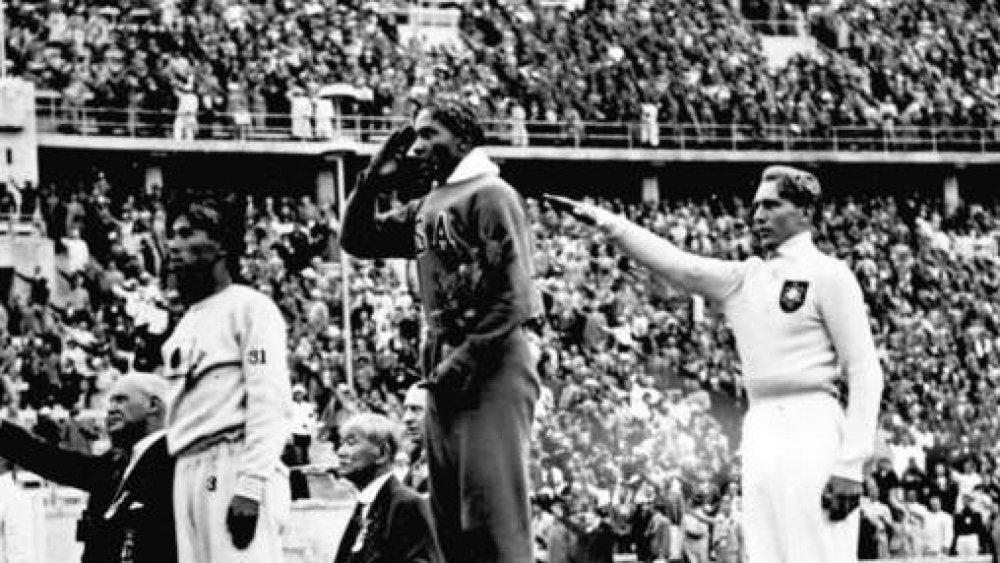

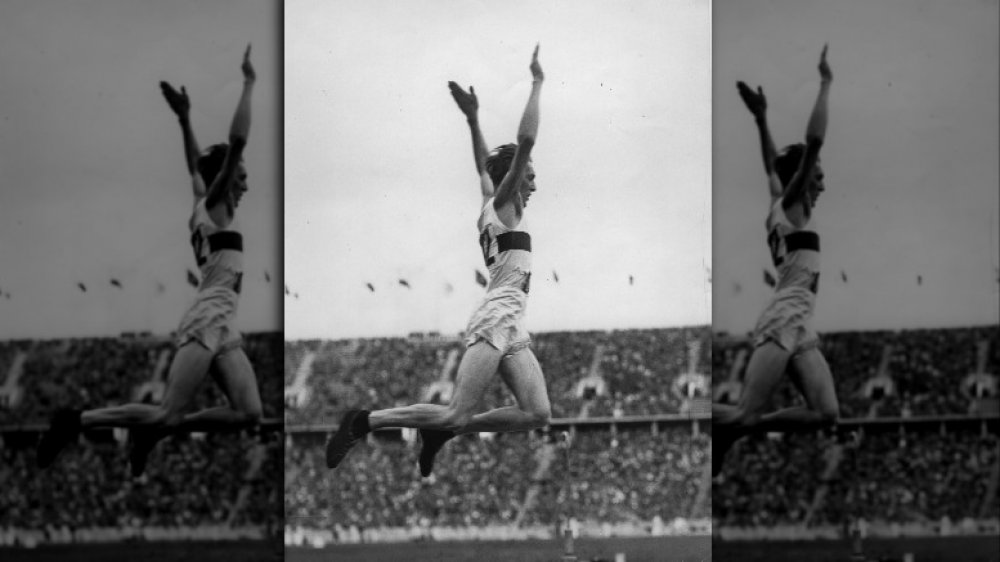

Jesse Owens made an unlikely friend at the 1936 Olympics

Jesse Owens came away from the Olympics with more than just four gold medals, global name recognition, and the satisfaction of humiliating the Nazis. In fact, Owens himself later wrote that the best thing he got out of the Games was a friendship — with an unlikely partner.

Blue-eyed, blond-haired German long-jumper Luz Long was Owens' competition at the Olympics. Owens was the world record holder, thanks to his jump at the Big Ten competition. But during qualifying, he fouled his first two attempts. According to Owens, Long advised him to move his mark back. Owens did, qualified, and went on to win the final that afternoon. Long took silver but congratulated him warmly, right in front of Hitler. Owens wrote in 1960, "You can melt down all the gold medals and cups I have received, and they wouldn't come close to outshining the 24-carat friendship I felt for Luz at that moment."

NPR revealed that Owens later admitted that Long didn't really help him during qualifying: they didn't meet properly until after the competition. But the friendship the two men developed was real. They exchanged letters until World War II broke out in 1939. Long was recruited into the German army in 1941. On July 14, 1943, he was shot by American troops in Sicily and bled to death. However, Owens started to write to Long's son Kai, and the two struck up their own friendship.

Jesse Owens wasn't the only exceptional African American athlete at the 1936 Olympics

Jesse Owens was the talk of the 1936 Olympics, but other African American athletes also performed Olympian feats. Of the 312 Americans, 18 were Black, according to NPR, and between them they won 14 medals (including eight gold) of the country's total medal count of 56.

John Woodruff came from behind to win gold in the 800m. Archie Williams won the 400m (and later trained Tuskegee Airmen.) Cornelius Johnson broke the Olympic record to win gold in the high jump, while teammate David Albritton took silver. Hurdler Tidye Pickett became the first African American woman to compete in the Olympics, but broke her foot in the semi-finals. Owens beat two of his Black teammates to win two of his medals. Mack Robinson took silver in the 200m: you may recognize him as Jackie Robinson's brother. And Ralph Metcalfe — who had beaten Owens in the 1932 Olympic qualifiers — took silver in the 100m. He also joined Owens in the record-breaking 100m relay, and later served in the House of Representatives.

There was racism within the US team. Louise Stokes was dropped from the 100m relay for a white runner. And Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller — the only Jewish members of the track team — were replaced with Owens and Metcalfe at the last minute, despite running faster than another team member. ESPN reported a rumor that the Nazis pressured US officials to make the switch.

Jesse Owens embarrassed Hitler — but returned to racism in the US

There's a famous story that Hitler was so infuriated by Jesse Owens' victories that he refused to shake his hand. In fact, after being reprimanded for only congratulating German gold medal-winners, Hitler had decided he wouldn't meet any athletes. But one world leader who specifically snubbed Owens was American President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Owens was hailed around the world for showing up Hitler's fascist white supremacist beliefs. But like other African American sports pioneers throughout history, back in the US, Owens and his Black teammates faced racism every day, including from their own President.

Unlike some of their white teammates, none of the African American Olympians received telegrams from Roosevelt, and none were invited to the White House. According to the Telegraph, at a reception held in his honor at the Waldorf Astoria, Owens and his mother were forced to use the freight elevator. ESPN reported that he later said, "I wasn't invited to shake hands with Hitler, but I wasn't invited to the White House to shake hands with the President, either."

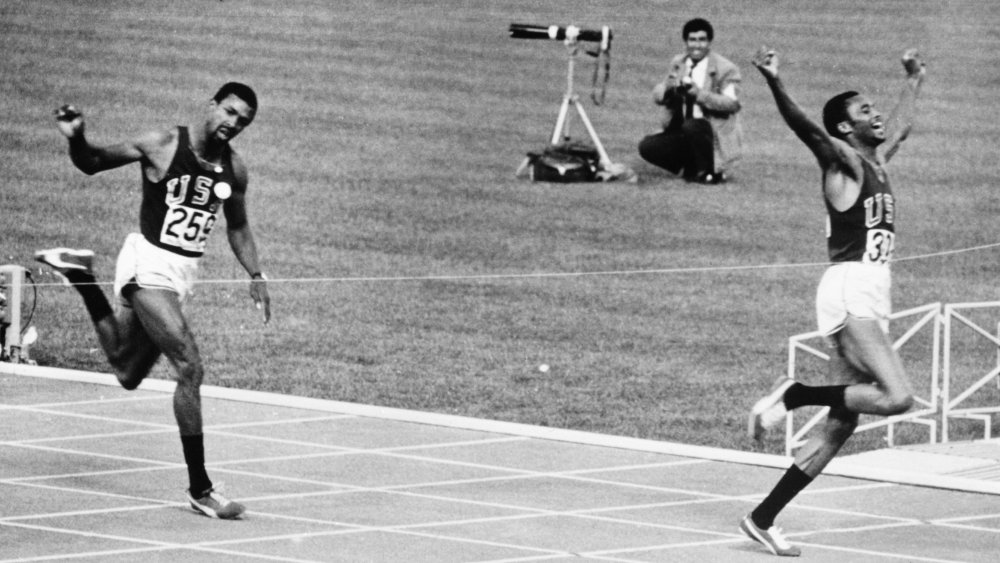

In September 2016, relatives of the athletes were invited to the White House to meet President Barack Obama, as a retrospective attempt to make amends. Tommie Smith and John Carlos were also honored: you know them as the two African American sprinters who were sent home over their Black Power salutes in the 1968 Olympics.

This is the secret to Jesse Owens' amazing speed

,Want to run and jump like Jesse Owens? You probably can't — he was a once-in-a-generation athlete, after all — but you can borrow his techniques. Owens combined his natural talent with a unique running style he learned from his first coach, Charles Riley, who was inspired by racehorses. Riley told Owens and his other students to run as though the track was on fire. The Telegraph quoted Owens describing it as: "I let my feet spend as little time on the ground as possible. From the air, fast down, and from the ground, fast up."

His second major coach, Ohio State's Larry Snyder, improved on a different part of his technique. Owens' weakest point during his races were his starts, which Snyder felt were too slow. He had Owens practice taking off from tight crouches. And for the long jump, Snyder taught Owens to move his legs in mid-air to gain extra precious inches.

You might not be able to hit Jesse Owens' speed or distances, but you could eat like him. Dr. Wilbur Harrison Smith Bohm recorded the diets of many of the American athletes participating in the 1936 Olympics, including Owens, to determine future training regimens. Owens reported eating lots of eggs and milk during training, and carrots, spinach, ice cream, more eggs, and tea right before competing.

The Olympics did not make Jesse Owens rich

Jesse Owens' achievements at the 1936 Olympics made him the most famous man in the world as well as the fastest, but it didn't translate into opportunities and wealth. The day after Owens won his fourth gold medal, the head of the American Athletic Union (AAU) and US Olympic Committee (USOC), Avery Brundage, sent him on a grueling unpaid exhibition tour to raise money for the two organizations.

After traveling around Europe with barely any time to sleep or eat, all while running races and doing long jumps, Owens had had enough. According to the Guardian, he left the tour and returned to the US, hoping to turn his Olympic fame into career opportunities. Brundage retaliated by stripping Owens of his amateur status, which meant he couldn't compete in many athletic competitions.

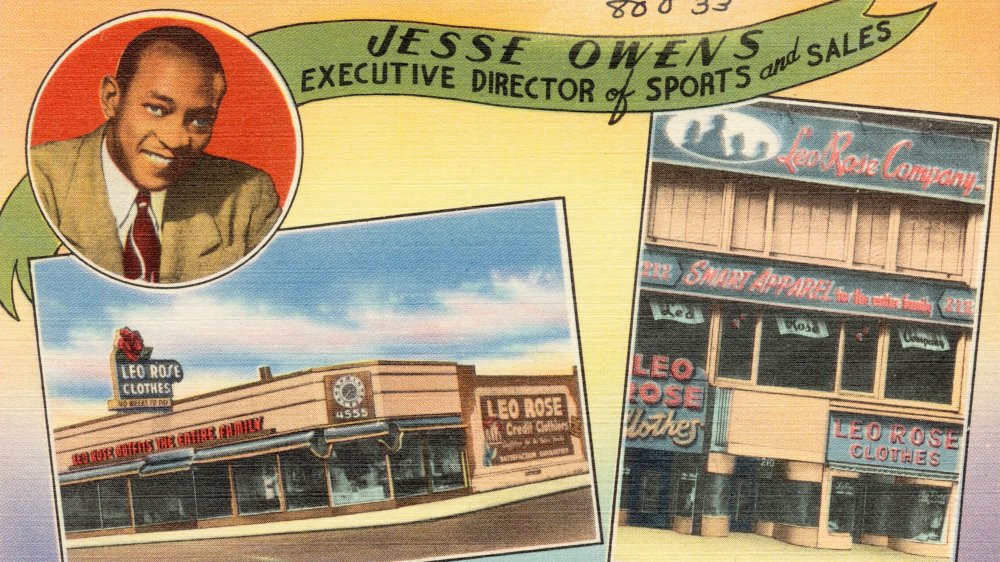

While Owens had been in Europe, he had been receiving lucrative offers for various public appearances. When he arrived home, these dried up. He resorted to racing trains, horses, and motorbikes for money. Later, he started a dry-cleaning business, but declared bankruptcy in 1939. Through the '40s, Owens held a variety of jobs, including selling sporting goods, head of personnel for Black workers at Ford, and touring with the Harlem Globetrotters. His finances improved in the '50s: he started a PR company in Chicago and became a motivational speaker, earning as much as $100,000 a year.

Jesse Owens tried to avoid politics

Jesse Owens' victories at the 1936 Olympics on Hitler's home turf made him an unwitting political symbol. And he did enjoy using his athleticism to defy racists in Germany and the US. He said, "If I could just win those gold medals... the Hitlers of the world would have no more meaning." But Owens generally preferred to keep out of politics, especially where race was involved.

When Owens and his Black Ohio State teammate David Albritton were refused service on road trips because of their race, Owens would try to diffuse the situation. According to the Telegraph, he once said, "I wanted no part of politics... The purpose of the Olympics, anyway, was to do your best... the only victory that counts is the one over yourself."

When Tommie Smith and John Carlos were kicked off the US Olympics team for raising the Black Power salute during the American national anthem in 1968, Owens — who was there — supported their punishment. He said that although he agreed with their anti-racism message, he felt that the Olympics were not the appropriate place for protest. He argued that their medals spoke for them: Smith had broken the world record in the 200m, while Carlos placed third. Later, however, Owens shifted his stance on Black Power. In his 1972 book I Have Changed, Owens wrote: "I realized now that militancy in the best sense of the word was the only answer where the Black man was concerned."

Jesse Owens finally found the recognition he deserved from his country

After being ignored in the '30s and forgotten in the '40s, Jesse Owens finally started receiving recognition for his accomplishments in the '50s. In 1953, he was made secretary of the Illinois Youth Commission, and in 1955 was appointed a goodwill ambassador for US sports, traveling around the world to promote American ideas and the benefits of exercise. At the same time, Owens became a sought-after public speaker in his own right. He was appointed to the US Olympic Committee's board of directors in 1973, and the following year, was inducted into the Track and Field Hall of Fame and awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Jesse Owens died from lung cancer aged 66 on April 1, 1980: his New York Times obituary reported that after quitting athletics, he'd smoked a pack of cigarettes a day for 35 years. Since his death, he's been memorialized in a wide variety of tributes. He has streets named after him in Berlin and Cleveland, OH. You can send a letter from Cleveland's Jesse C. Owens Post Office with a 1992 or 1998 Jesse Owens stamp. Aspiring young athletes can burn off energy in New York's Jesse Owens Playground. And in his birthplace of Oakville, AL, you'll find the Jesse Owens Museum. The US was slow to celebrate the world's fastest man, but at least it's trying to catch up.