What Life Was Like For U.S. Marshals In The Wild West

We've got plenty of notions about the Wild West. Thanks to various films, television shows, novels, and more, many of us assume that it was a harsh place. We see it full of dusty, squalid little towns and overrun by bandits. Very often in these imaginings, a hero of sorts arrives to put things right, be they a square-jawed man in a white hat or an antihero with a half-grown beard.

The Wild West, also often called the Old West, was a period of expansionism into Native American territory, spanning from the middle of the 19th century and into the 20th. Because this was a frontier for many, law enforcement could be scant, though perhaps it wasn't as dramatically violent as The Good, The Bad and the Ugly would have you believe. Then again, there were indeed violent gangs and outlaws wreaking havoc across vast territories. Someone had to reel them in.

Enter the U.S. Marshals Service. The Marshals and their deputies have actually been around since 1789, when the Judiciary Act created the agency. It essentially created the marshals to be agents of the federal court system. They were empowered to support the courts and carry out a judge's orders. A marshal could swear in deputies, who then carried out the on-the-ground work as needed. In the Wild West, this included law enforcement and the capture of fugitives. Sometimes, the marshals' experiences lined up with our imagination. Sometimes, it was surprisingly different.

A U.S. Marshal could face incredible danger

Sure, many of us have romantic notions about U.S. Marshals roaming the Wild West, dispensing law and justice throughout the land while wearing a cool hat. But let's get one thing straight: Being a U.S. Marshal was heinously life-threatening. Think about it. You're a deputized agent of the Department of Justice. As a deputy U.S. Marshal, it's your job to track down fugitives, which, in the Wild West, typically meant dangerous criminals who had to be apprehended and turned over to the legal system. Few of them would be willing to come along quietly, and many were armed to the teeth. You had to be ready for violence in a place where the law could be seem terribly thin at the best of times.

Consider one of the deadliest days for the U.S. Marshals: April 15, 1872. In the Going Snake Massacre, eight deputy marshals were killed by members of the Cherokee tribe. Ten marshals had been approaching a schoolhouse on the tribal reservation, tasked with retrieving a man who had just been acquitted of murder by the Cherokee court.

Seeing the marshals approaching, a few Cherokees exited the building and opened fire. It's not clear whether or not the marshals had drawn their own weapons before the gunfire began. Neither is it entirely clear how the tribespeople saw the approaching group. Did they fear violence from an unidentified posse? Regardless, seven deputies died at the scene, and another passed hours later.

The U.S. Marshals were part of a confusing political network

As lawless as the Old West could be, there was sometimes a bewildering mix of law enforcement officers to track down criminals. U.S. Marshals and their deputies acted alongside an array of sheriffs, Texas Rangers, military officers, civilian-led posses, and more.

Like many government agents, the marshals could also be subject to the whims of politics. Frequently, whenever an appointed U.S. Marshal retired or was asked to step away from their office, most of their deputies were likewise replaced, says The United States Marshals of New Mexico and Arizona.

Remember that marshals also couldn't just charge out to apprehend evildoers, no matter what all those westerns might have you believe. No, they had to wait for the paperwork to come through. Without a proper warrant and the oversight of a government agency, a marshal would have been little better than the criminals they were pursuing.

Not all of the U.S. Marshals were men

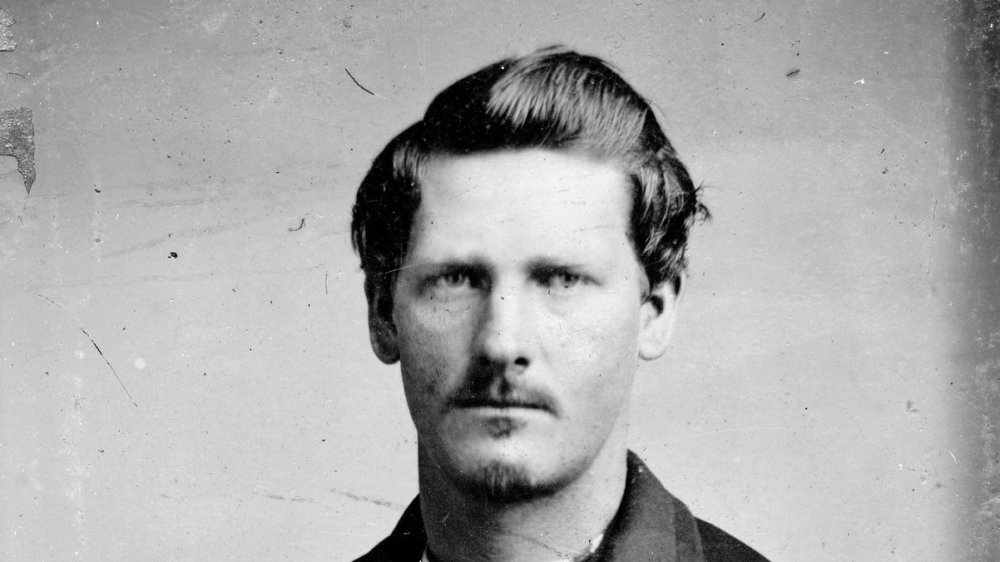

When you picture a U.S. Marshal galloping across the Wild West, who do you see? Chances are it's someone like Wyatt Earp, who served as a deputy marshal. You know the picture, right? Grizzled, big hat, equally large mustache, gun at his hip and a tin star pinned to his chest. But that's not the whole story: "He" could have been a "she." Though they never outnumbered the men in the service, a notable number of women also served as U.S. Marshals. They were often relegated to desk work, naturally, as many of their superiors assumed that women were simply unable to handle the intense nature of field work.

Some female U.S. Marshals, however, made arrests and tracked down fugitives just like their male counterparts. These include Ada Curnutt, who tracked down two outlaws in Oklahoma City in 1893. As told in Oklahoma Justice, she'd been instructed to send out a deputy. As all deputies were out in the field already, Curnutt took the task upon herself. She boarded a train to Oklahoma City and found the men in a saloon. She presented such an improbable figure that they laughed and let her handcuff them, only to realize too late that she wasn't joking.

F.M. Miller was another deputy marshal working in Texas during the 1890s. A November 6, 1891, article in the Fort Smith Elevator describes her excellent riding and shooting skills, saying that she was "brave to the verge of recklessness."

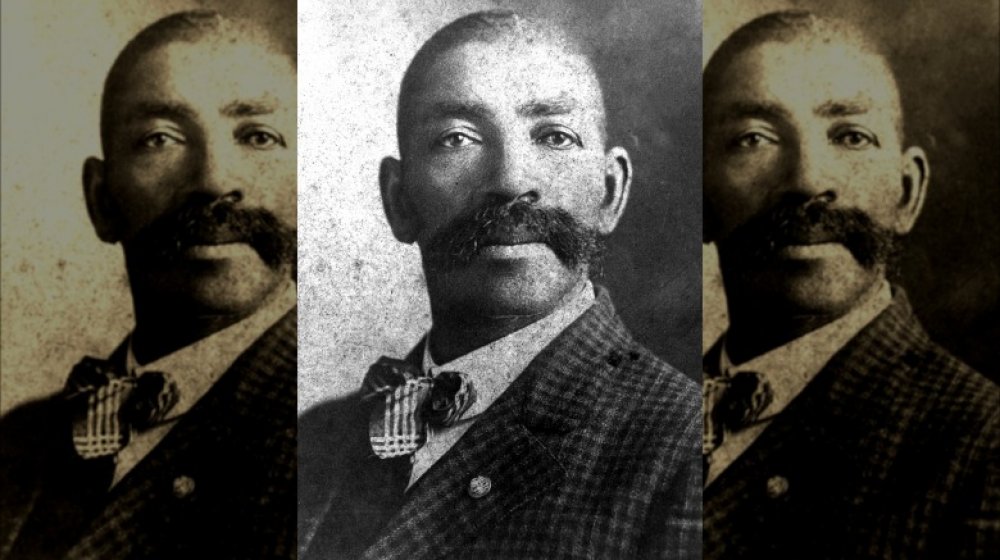

One of the greatest U.S. Marshals was a former slave

Bass Reeves was the first Black deputy U.S. Marshal west of the Mississippi, becoming well-known for his reliability and relentlessness. Reeves was so legendary that he became the inspiration for film and TV's Lone Ranger. He was born into slavery in 1838 in Crawford County, Arkansas, according to the Texas State Historical Association. Reeves eventually fled slavery after beating his master over a card game gone wrong. He hid with Native Americans in the Indian Territory until the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1862. Now legally considered a free person, Reeves became a farmer and family man.

It's clear that Reeves did not settle down into a sleepy domestic life. In fact, danger came looking for him. When Isaac Parker, the infamous "Hanging Judge," was appointed to the area, he specifically recruited Reeves as a deputy marshal. Reeves already had an in with the Native Americans, having learned their languages and earned their trust during his fugitive years. Native people also suffered extensive abuse at the hands of white criminals and therefore distrusted white officials. To Judge Parker, Reeves was the perfect man to mediate between whites and native people.

Reeves soon became renowned not just for his skill in apprehending criminals but for his strict adherence to the law. He even tracked down his own son, Bill. According to Black Gun, Silver Star, Reeves followed him for two weeks before finally apprehending him and turning him in to the courts.

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral complicated the U.S. Marshals' legacy

We've all heard of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. It's a hallmark of Wild West history that saw honorable lawmen facing off against dastardly outlaws. But is that really how it happened? The 30-second gunfight left serious questions.

The October 1881 shooting was the result of a feud between lawmen and a group of civilians, sometimes called the Cochise County Cowboys. Of the cowboys, Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury were killed in the shootout. The lawmen included Wyatt Earp, a deputy marshal known for his hard living and, per the National Park Service, occasional horse-stealing. Earlier in his career, according to History, Wyatt was even booted off the Wichita police force after walloping a candidate for sheriff. The other members of Wyatt's group were his older brother, Virgil, the deputy federal marshal and acting police chief of Tombstone, young brother Morgan Earp, and a tuberculosis-ridden dentist called Doc Holliday. All had been deputized by Virgil for the confrontation

Ike Clanton later filed murder charges against the group, but despite the testimonies of many who were at the scene, the charges didn't stick. Where the law didn't get vengeance, someone apparently did it themselves. Morgan Earp was killed in March 1882, shot by an unidentified assailant while playing billiards in a saloon. Wyatt's resulting vendetta led to further death and a dramatic but violent addition to the legacy of deputy U.S. Marshals.

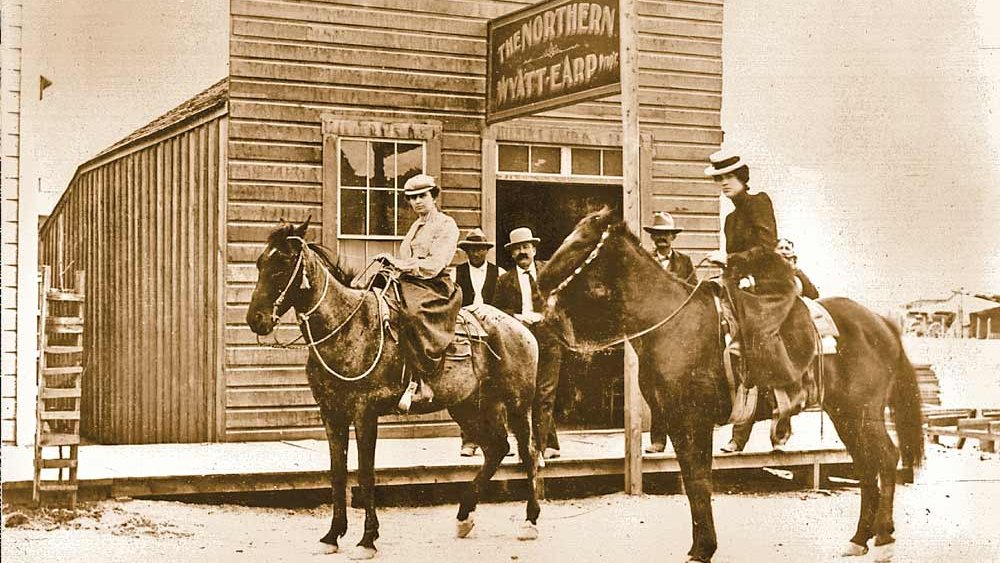

The Earps maybe weren't the best representatives of the U.S. Marshals

In retrospect, the U.S. Marshals probably weren't so proud of the Earp brothers as the movies might want you to think. Wyatt Earp, for one, was perhaps better at raising hell and running saloons, and the embarrassing truth is that he might not have made it in the modern U.S. Marshals Service. For one, Marshal Eugene Davis noted that Wyatt would have faced some serious questions when it came time to run his background check. His lack of a college degree and penchant for fistfights could make modern recruiters leery as well.

Younger brother Morgan was a fellow lawman and sometimes marshal who was killed by one of the remaining Cochise County Cowboys, says an article from Wild West Magazine (via HistoryNet). Wyatt proceeded to go on an infamous vendetta ride against the remaining cowboys. Both Wyatt's and Morgan's apparent loyalty to family over the law would also raise eyebrows both then and today.

Virgil, their elder brother, was at least a more legitimate lawman, serving as a long-term, though sometimes piecemeal, officer. Virgil was elected to various marshal posts and sheriff's offices and even worked for a time as a stagecoach driver and miner. It may not be fair that his rowdier younger brothers have overshadowed him, but Virgil comes out looking better for the comparison. At least he might make it past the U.S. Marshals' recruitment stage today.

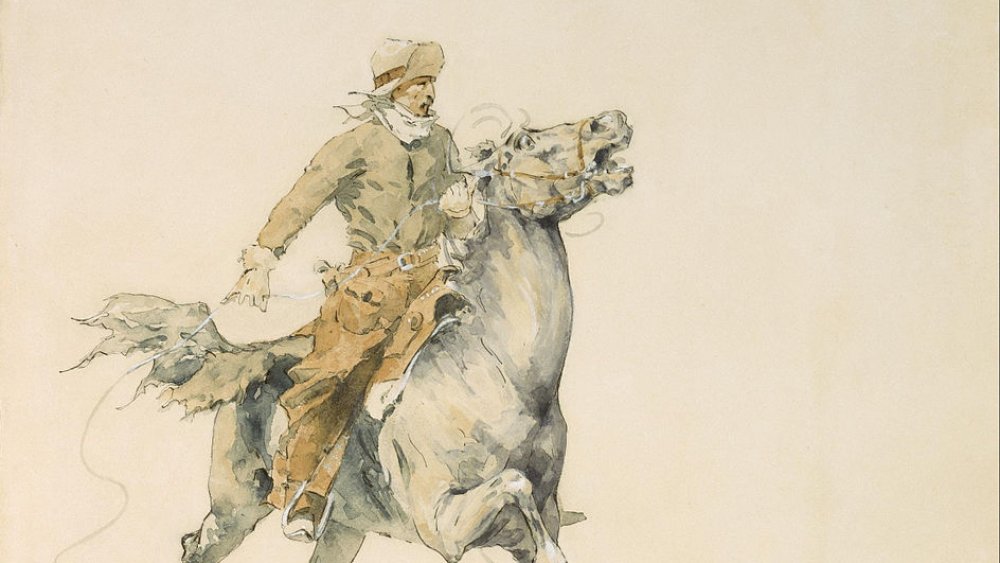

Marshals had to like riding horses

Wyatt Earp's early rap for horse-stealing may not be fair, says True West Magazine, but the hatred of horse thieves serves to illustrate the importance of these animals to marshals and criminals alike. The truth of the matter, as seen at the National Cowboy Museum, is that getting around the Old West was a chore. Sure, you could eventually take trains to some settlements, which tended to thrive around railroad stops. Stagecoaches and wagons were also an option. That only took you so far, however. It's not as if the train would take you straight to an outlaw's door.

For marshals, tracking fugitives could mean long hours on horseback in punishing conditions. In one case, described in Too Tough to Die: Down and Dangerous with the U.S. Marshals, lawmen Pat Garrett, Thomas K. McKinney, and John W. Poe went 81 miles through New Mexico on such a trip. The man they wanted had escaped from jail in April, killing two sheriff's deputies in the process.

They rode at night, avoiding roads and sleeping rough with only their saddle blankets for cover. They rode into Fort Sumner in July 1881, using a network of informants and some discreet questioning to find their target. That alone wasn't easy, considering that the man went by the names Henry McCarty, William H. Bonney, and "Billy the Kid." The trio found him on July 14, when he was surprised and shot to death by Garrett.

Marshals could be like Terminators

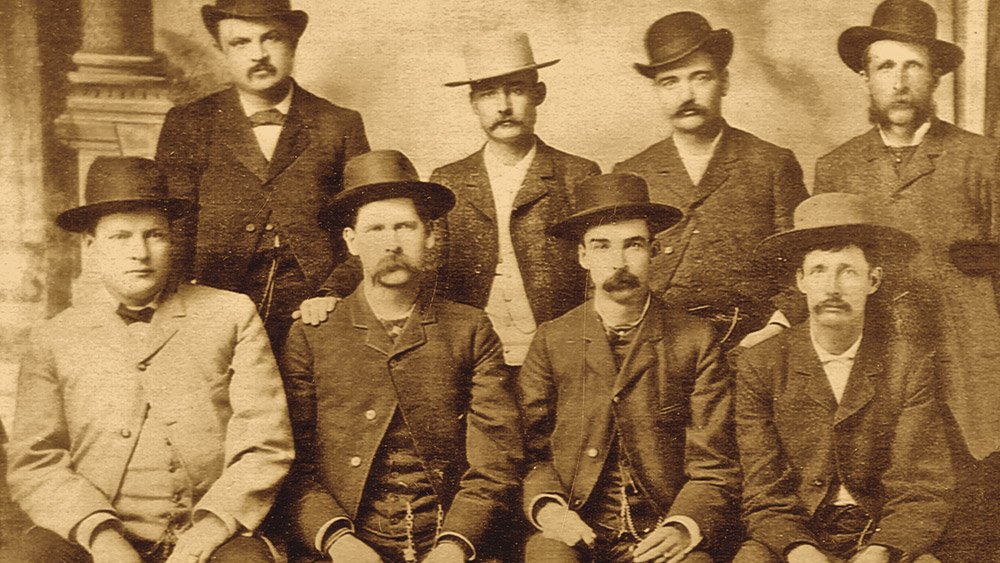

U.S. Marshals were not known to give up. If you were named in an arrest warrant, it could seem like they would only stop when, desperate and exhausted, you were either dragged into court or the local undertaker's office. Take the "Three Guardsmen," who pursued the Doolin-Dalton Gang with relentless drive. The gang had become notorious for their deadly train heists, says the U.S. Marshals Service. The Three Guardsmen, all deputy U.S. Marshals, were Bill Tilghman, Chris Madsen, and Heck Thomas (pictured above). They worked under Marshal E.D. Nix in the notoriously wild Oklahoma Territory.

According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, the trio first teamed up for their pursuit of the Doolin-Dalton gang in 1891. They spent the next five years pursuing the group, picking off individual members as they encountered them. They worked like a cinematic trio of superheroes, each with their own individual specialties. Madsen was their organizer, Thomas the best marksman, and Tlighman the most skilled tracker.

E.D. Nix was therefore like their Charlie Townsend, if Charlie's Angels were grizzled, gun-toting marshals riding rough through 19th-century Oklahoma. It probably didn't seem so cute to Bill Doolin, the gang's leader and last free member, who was shot by the Three Guardsmen in 1896.

U.S. Marshals were also the law's administrative department

U.S. Marshals had to keep the judicial system running. It wasn't as exciting as shootouts, but they needed an administrative backbone. You could indeed argue that all that paperwork helped to put them on the right side of the law.

U.S. Marshals were and still are agents of the legal system. As much as some accounts glamorize their pursuits, they were ultimately government employees whose jobs required a lot of paperwork. Their work certainly didn't end once an arrest had been made. Once a deputy marshal had apprehended a wanted person, they had to make sure that the criminal had their day in court. During the era of the Wild West, marshals took on the nitty-gritty of arranging trials, assembling juries, securing courtrooms, and even hiring janitors to clean up the place, says Legends of America.

Sometimes, deputy marshals would be dispatched into the world for less violent work, as described by the New York Public Library. In the earlier days of the Wild West, that included a lot of tasks now done by a variety of modern agencies. Marshals could be seen taking census data, overseeing elections, and even acting as tax collectors. This was unlikely to make them popular, but these duties are what kept many communities together during a tumultuous time in American history.

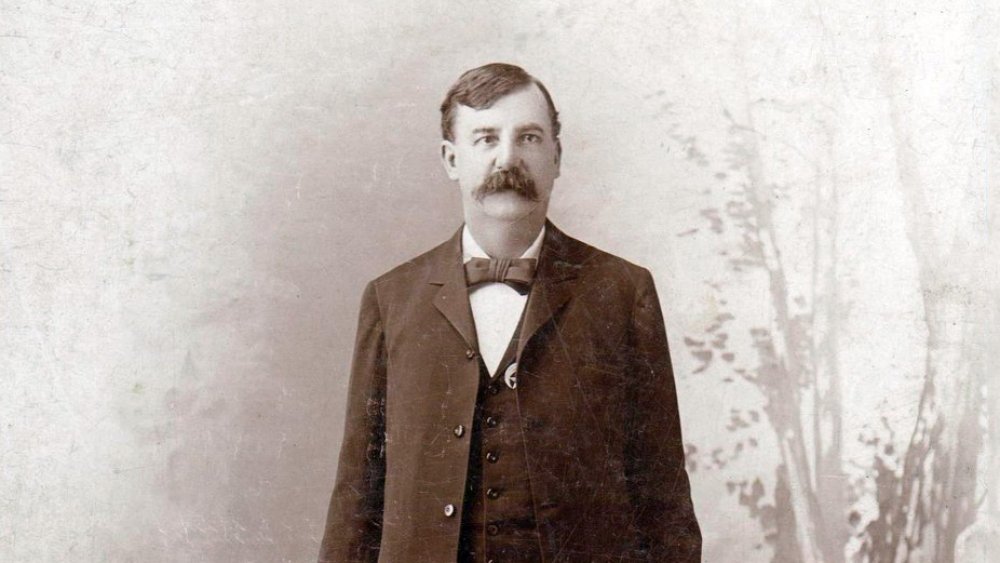

One U.S. Marshal found fame by settling down and writing

Like many lawmen of his time, W.B. "Bat" Masterson did his fair share of adventuring throughout the Wild West. He also had a bit of a checkered past, thanks to his reputation as a gunslinger with something of a sensitive trigger finger.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, Masterson started off normally enough, with a family that moved into Kansas in the 1870s. Wanting some more adventure than home life could offer, he left them to work as a hunter and teamster and, eventually, in law enforcement. By the end of the 1870s, he was a deputy marshal in Dodge City, Kansas. After Masterson lost the election for sheriff of Dodge City, he went to Leadville, Colorado. There, he became a gambler, befriended Wyatt Earp, and followed his new bud to Tombstone. He would also show up in Las Animas, Colorado, and Fort Worth, Texas, where he worked in a saloon after an ever-so-brief stint as a prohibitionist, says author Robert K. DeArment.

Eventually, it looked as if Masterson was ready to settle down — he got married and moved to Denver, Colorado. However, he and his wife, Emma, moved to New York City after Bat's gambling buddies started causing trouble. That's where Teddy Roosevelt made Masterson a deputy marshal again in 1905. By then, according to Smithsonian Magazine, he had already started a journalism career that would cement his legacy with a series that retold his frontier adventures.

One of the last Old West Marshals caught wolves bare-handed

In the American West, almost everyone hated wolves. These predators were menaces to the herds of domestic animals installed on ranches throughout the region, namely sheep and cattle. Over time, people developed an oversized distaste for the animals that ignored their vital place in the environment, says Environmental Review. For many, a wolf pack might as well have been snatching money directly out of a family's bank account.

"Catch 'Em Alive" Jack Abernathy was committed to catching wolves in what is now the state of Oklahoma. But where others would simply resort to trapping or poisoning, Abernathy took a unique tack. He reportedly learned that he could take wolves alive by jamming his hand down their throats, which prevented them from biting down, reports Legends of America. Abernathy sold the wolves to parks, zoos, and other attractions, which was at least better than an agonizing death by wolf trap or strychnine.

He also ran his own wolf-centric show, which caught the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt. After befriending Bat Masterson, Teddy had apparently begun cultivating a habit of appointing people to law enforcement posts based on their wild pasts. In 1906, he made Abernathy the then-youngest U.S. Marshal, says 405 Magazine. This put him in charge of the Western District of the Oklahoma Territory with an a salary of $5,000 per year. Ultimately, as claimed by the White Mountain Independent, he sent around 800 criminals to the courts.