Here's Who Eleanor Roosevelt Wanted On Mount Rushmore

So there are these granite cliffs out in the southwest corner of South Dakota, kind of near Keystone (population 337, as of the 2010 census), and at some point about a hundred years ago somebody said, "Boy howdy, wouldn't Teddy Roosevelt look good up there?" Never mind that it was sacred territory to the Lakota tribe of the Great Sioux Nation, as Mental Floss reminds us. ("What if we added Lincoln? Are you sold yet?") The site was Mount Rushmore, named for a New York attorney back in 1884 who was far from the first human being to lay eyes on the thing, but for some reason got naming rights.

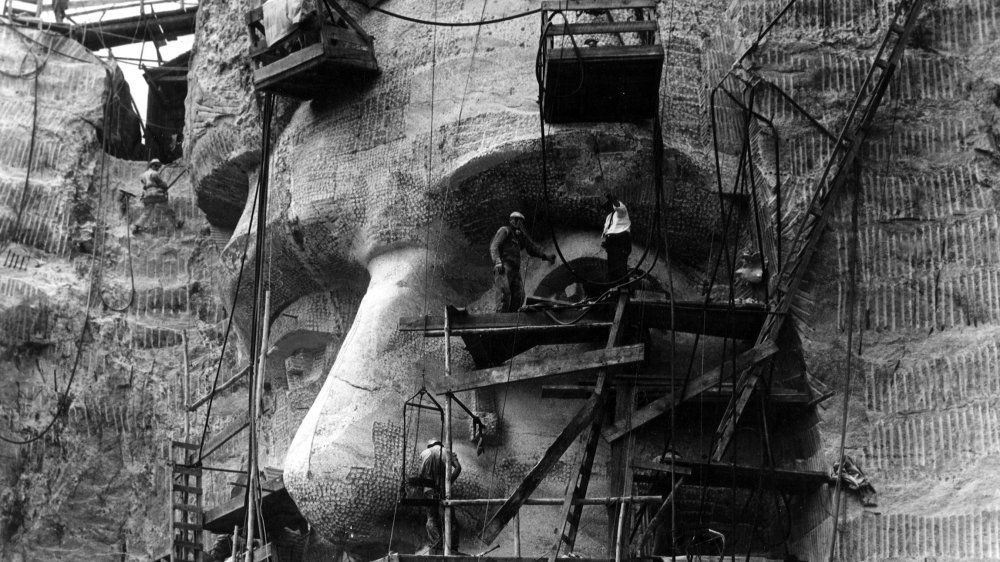

Scoot ahead. Gutzon Borglum was a sculptor working on a mountain-carving project celebrating figures of the Confederacy in Georgia. Some 10 years in he got canned. As the National Parks Conservation Association tells it, a South Dakota historian named Doane Robinson had come up with the idea of a mountain-carving-thingie to attract tourists (what, people weren't coming to South Dakota already?) and contacted Borglum who, by 1925, was available. (The talent pool of mountain carvers couldn't have been that deep. No criticism intended.) Robinson wanted a memorial to figures of exploration and settlement of the Western Frontier — Lewis and Clark, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Lakota chief Red Cloud. Borglum not only chose Rushmore, but chose the theme: presidents responsible for the development and expansion of the nation, says the National Park Service.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt had ideas about who should be included

Right away, there were people asking, "But does it have to be those guys?" Specifically, "guys," because they all were — George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. According to History, carving began in 1927, which is about the time Rose Arnold Powell wrote to President Calvin Coolidge, strongly suggesting that women's rights activist Susan B. Anthony be added to the display. Said Powell later, "Many a thrilling story of feminine heroism lies buried, which if resurrected would inject an element which in American life is missing, and it would deflate masculine superiority. ..." Powell broadened her campaign for Anthony by writing to and meeting with Borglum himself; big no. She kept up the pressure as work continued, going so far as to write to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who responded on her own with a letter to Borglum in 1936, when completion of the work was only three years away. Borglum protested that, in addition to the enormous cost of adding another head to the display, Anthony's inclusion wouldn't have fit his artistic vision.

Will the future see an addition to the monument?

"No man living has a greater respect or a greater admiration for, or places woman in a more lofty position in civilization than I do," responded Borglum. "I have resented all my life any and all dependence or second place forced upon our mothers, our wives or our daughters, as has been the history of men's civilization, but I feel in this proposal that it is a very definite intrusion that will injure the specific purpose of this memorial." So, no. Congress considered a bill later that year to remedy the Anthony exclusion, but it failed to pass.

There have been numerous suggestions over the years for additions to the quartet. Opinions vary as to whether it's physically possible — Borglum felt he'd used all of the viable space for the memorial as it now stands — but perhaps mountain carving technology has advanced sufficiently to make it a quintet. USA Today reports that a Texas stone carver, Stuart Simpson, posited in 2017 that with sufficient funds — $64 million for labor alone — and time — he guesstimated four years — it could be done. Which then raises the question of who to add. And that's a whole other kettle of fish. Er, granite.