The True Story Of The Ancient Aztec Capital Of Tenochtitlan

The ancient Aztec city of Tenochtitlan is the source of a flood of fascinating history. Then again, it's also the source of many fascinating rumors and half-truths. Thanks to the Spanish conquistadors who overtook the city in 1521, led by Hernán Cortés, misinformation about Tenochtitlan and its inhabitants has been around for 500 years. Those errors still persist today. For instance, some of us might still think of the Aztecs as bloodthirsty conquerors. While war was a central part of their society, as Aztec Warfare explains, that's not the whole story. We also can't really trust the word of Cortés, who had a stake in making Aztec society look as rotten as possible in order to pretty up his own brutal conquest.

We do know that the empire he encountered was part of a complex system of culture, religion, warfare, trade, and deep memory. The story of Tenochtitlan, the largest city in the region, is part of a much larger history of Mesoamerican people going back thousands of years.

It's important for us to get this story right. It encompasses the history of a people whose descendants are still alive today, whose buildings are still being revealed in the middle of Mexico City and beyond. The real history of Tenochtitlan is just as dramatic as any tale you've encountered.

They didn't call themselves Aztecs

Imagine that you were somehow able to travel back in time and walk through the streets of Tenochtitlan at its height, just before Hernán Cortés came and basically ruined everything. You'd see a huge city full of people, packed with houses, markets, farming plots, and an imposing temple. Now, imagine wandering up to a market stall and asking the person inside what they call themselves. No one, not a single person, will answer "Aztec."

That's because the term "Aztec" isn't quite right for the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan, explains Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs. Writers in the 18th century, long after the Spanish conquest, used that word to describe what was really a vast group of people. This includes the dominant group that lived in Tenochtitlan, who called themselves the Mexica. Other "Aztecs" would be far more likely to refer to themselves by city-state. Someone from Tlaxcala would probably say they were Tlaxcalan, or a person from Tabasco a Tabascan.

Most people were able to communicate through a common language, Nahuatl. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, it's still spoken today. That's thanks in part to native people who wrote it down in the 16th century, before the language disappeared under Spanish rule.

One legend claims that an eagle and a cactus were part of Tenochtitlan's origins

Before Tenochtitlan, the Mexica people were wandering the land, looking for a home. It was the 14th century and the Mexica were newcomers to what is now central Mexico. According to Chungará, much of the land might as well have had a "no vacancy" sign, since people like the Olmecs and Toltecs had been there for centuries. That meant the Mexica were often unwelcome guests in someone else's city, like awkward, visiting cousins. What they really wanted, more than anything else, was a place of their own. They prayed for help to Huitzilopochtli, the god of the sun and war.

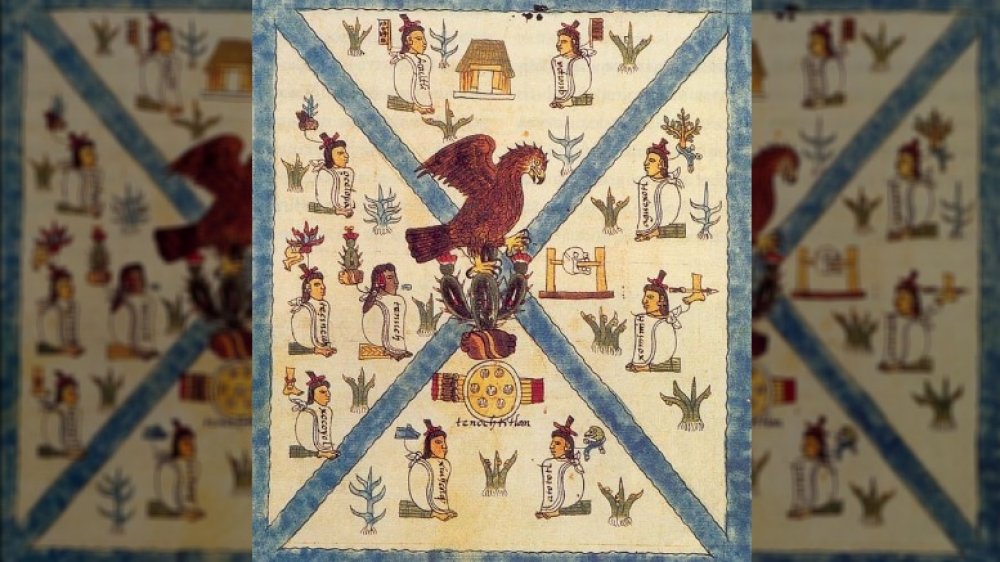

In one of the most famous versions of the tale, Huitzilopochtli came through with a striking vision. The Mexica found an island in the middle of a salty, swampy lake in a valley. There, they saw a great eagle land on a prickly pear cactus, a snake caught in its beak. This, said Huitzilopochtli, was a sign that they should settle on the very spot. When your primary god says to do something, you do it. The Mexica started building right away in the middle of what was eventually called Lake Texcoco.

The story of the eagle was so powerful that it's survived to the present day. In fact, the Mexican flag has the very same symbol at its center.

Tenochtitlan was an engineering marvel

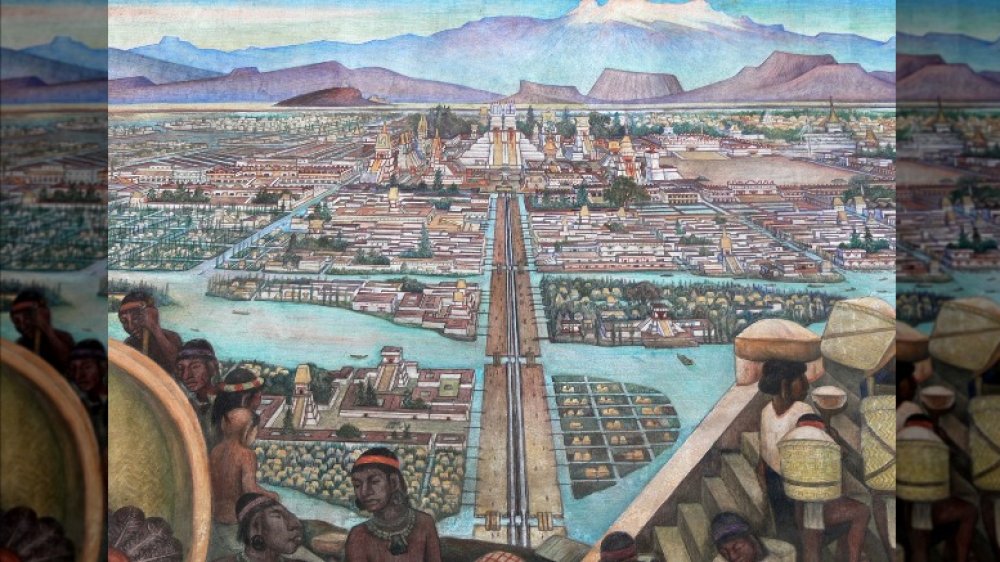

Soon enough, the swampy island in the middle of Lake Texcoco was transformed. The Mexica set about building chinampas, described by the United Nations as small agricultural plots built up out of the surrounding earth that floated on top of the water. As more and more chinampas were built, the growing settlement literally gained ground as it turned the lake into solid land.

A sophisticated system of canals separated the brackish salt water of the lake from freshwater runoff higher up in the basin. These fed the growing chinampas and created a watery highway through the city. Someone navigating Tenochtitlan could theoretically do so entirely by canoe. Thanks to its engineering and location, the city prospered. In only 80 years, says LiveScience, the collection of huts by a swamp had become a power center.

Tenochtitlan was full of monumental architecture and well-planned city streets. In a letter to the Spanish king, Cortés said that the streets and causeways across the lake were beautifully made. They were so well-done, he said, that the people could turn them into defensive measures pretty easily. As Cortés learned the hard way, he was right.

Tenochtitlan's main temple was designed to impress

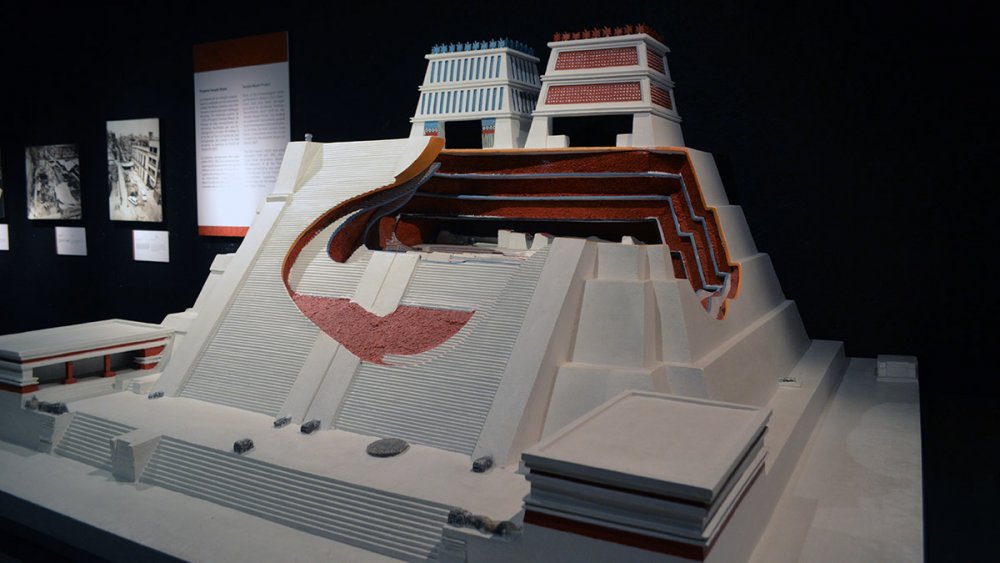

At the center of Tenochtitlan lay one of the grandest, most imposing pieces of architecture in the whole region: the Templo Mayor. It was a large stepped pyramid, rising 90 feet into the air, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The complex soared far above anything else in the city. It was topped by two temples dedicated to the gods and covered all over with the best carvings and decorations that the empire could muster. These include the Coyolxauhqui stone. Khan Academy says the stone is a beautifully-made carving uncovered in 1978 that shows the gruesome fate of Huitzilopochtli's sister after she attempted to kill their mother.

All of this was a tremendous amount of work to build, but you want to impress some of the biggest deities in your cosmos, right? The Aztec Templo Mayor: A Visualization says that one of the temples was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war that gave the signal to found Tenochtitlan. The other went to Tlaloc, the all-important god of rain and agriculture.

Like many grand pieces of civic architecture, the temple changed according to each city leader's plan. It was rebuilt six times before the Spanish conquistadors invaded. Google Arts and Culture says Cortés' forces razed the seventh temple to make way for a cathedral, the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City.

Tenochtitlan wasn't alone

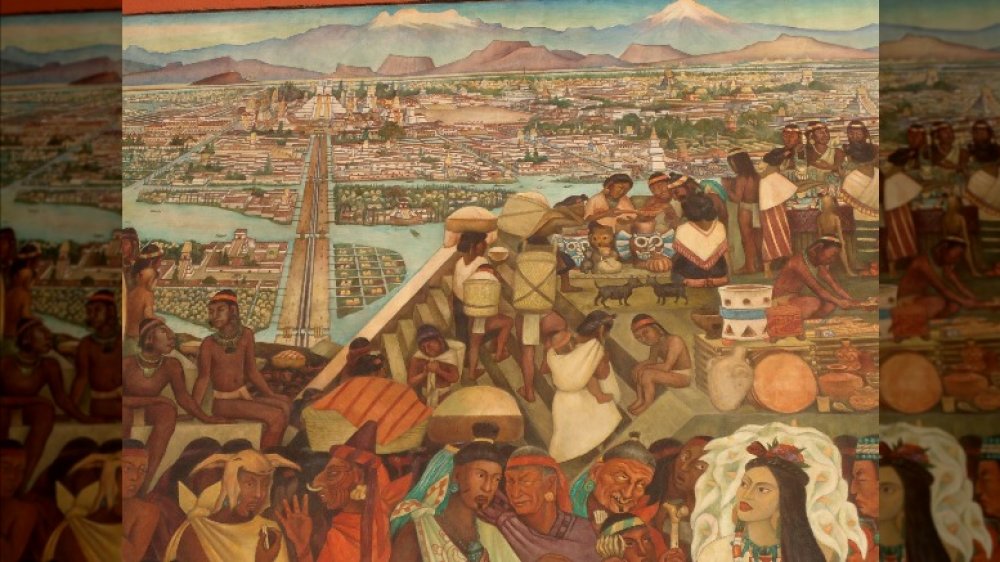

While Tenochtitlan became the big name in the area, it wasn't the only player in this game. A large number of people lived in city-states that were part of a complex and sometimes violent system of war and trade. It wasn't even the only major settlement around. Texcoco: Prehispanic and Colonial Perspectives says that the area was teeming with people. Tlacopan was so close that you could reach it in a short canoe trip.

A slightly longer boat ride would get you to Culhuacan in the south, then Xochimilco only a bit further on. And that's only talking about the cities around one lake system. Other, more far-flung settlements, like Tabasco, had the dubious honor of meeting Cortés first when he sailed in from the Gulf of Mexico.

Tenochtitlan found it beneficial to form alliances with nearby cities, especially Tlacopan and Texcoco. The idea was that these three settlements would form a "triple alliance." Then again, that was more a matter of political convenience and polite white lies. Everyone knew the real power came from Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma II, the last ruler of the city, eventually became the biggest name in the Aztec world.

Moctezuma II wasn't just some city mayor

If you lived in Mexico at the time, you'd do well to treat Moctezuma with some respect. He wasn't just a mayor or even a high-flying politician. His power was rooted in political might, religious force, and the weight of a big-time family lineage, as outlined in Conquest: Cortes, Montezuma, and the Fall of Old Mexico. Moctezuma II's power stretched over a vast region, bringing the Aztec empire to its greatest extent just before the Spanish made contact. Millions of people were expected to take part in a complicated economic system that supplied food, trade, and prisoners to Tenochtitlan and its ruler.

When Cortés arrived in Tenochtitlan, Moctezuma treated him as a fellow noble, according to the Florentine Codex. It was a cautious, politically calculated move. They didn't know who this newcomer was, exactly. Moctezuma, who was by then an experienced ruler, wasn't about to make a rash move.

By the way, the notion that the native people thought Cortés was a god doesn't hold water, according to JSTOR Daily. Moctezuma's later actions and the Mexica resistance to conquest point to their understanding that these invaders were mortal beings like them, not deities.

Human sacrifice definitely happened

We can't deny the fact that human sacrifice was part of life in Tenochtitlan. Spanish conquistadors were taken aback by what they saw, however. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, a soldier who was part of the Cortés expedition, described the practice in gruesome, shocked detail. It served as justification, alarming enough people in Europe for them to wave away the similar horrors of conquest.

The truth of human sacrifice in Tenochtitlan is more complicated than Diaz and others thought. It's almost certainly true that human sacrifice was used to frighten and intimidate across the empire. Chemical analysis of bones found in the city, shown in Science, proves that sacrificial victims came from many different regions. They may have been slaves sold in the marketplace, warriors captured in battle, or regular citizens selected for the role. Human sacrifice was also a vital part of religious belief. To empower the gods and stay in their good graces, people were obliged to sacrifice members of their own community. Skulls of victims were displayed in racks called tzompantli or cemented into large towers, as described by Reuters.

Some captives even expected to be sacrificed and were enraged when their fates were slow in coming, as in the story of Shield Flower told in Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs. As a noble in enemy hands, she demanded her own sacrifice after her captors dragged their feet.

Cortés took advantage of Tenochtitlan's unsteady position

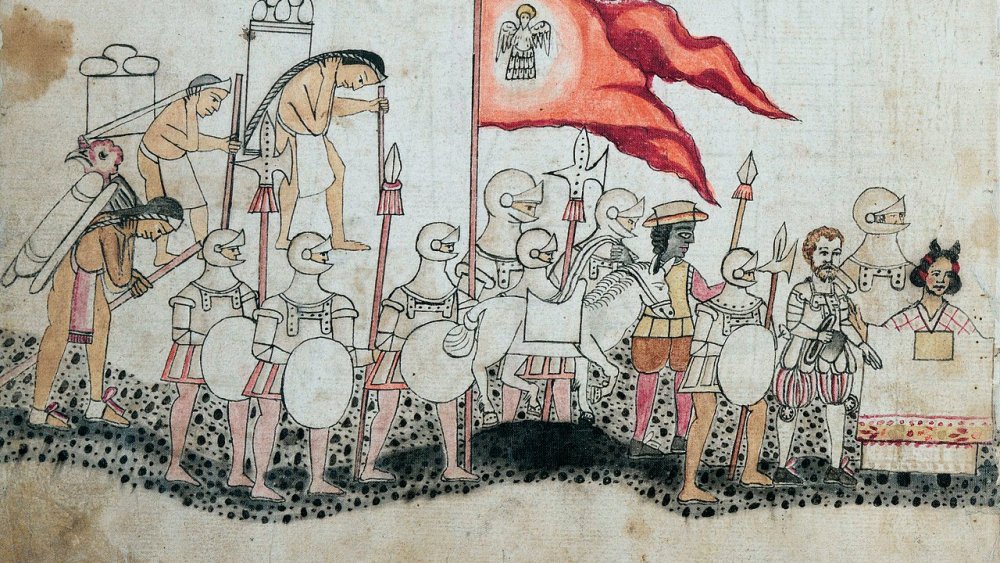

Few city-states sat easy, including Tenochtitlan. Other settlements greatly resented contributing hard work and people to Tenochtitlan's well-being, like the city's arch rivals in Tlaxcala. When Cortés arrived on the Gulf Coast in 1519, Live Science says he allied himself with these groups and used them to get into Tenochtitlan.

Though Tlaxcalan leaders were suspicious of the Spanish, they teamed up anyway. HistoryNet outlined the basis of Tlaxcala's decision, saying that it was rooted in inequity and rivalry. Their antipathy towards Tenochtitlan, which demanded food, treasure, and sacrificial victims for its own benefit, was simply too strong. Since Tenochtitlan and therefore Moctezuma were in a near-constant state of suspicion, that made it all the easier for Cortés to work his way into the upper echelons of the city. Once there, his forces quickly imprisoned Moctezuma, upending the existing power structure and further weakening Tenochtitlan.

Though the shine had quickly worn off the Spanish visitors, Cortés wasn't done wreaking havoc. Moctezuma died soon after his imprisonment, though we don't know whether it was at the hands of his own people as ThoughtCo. claims, or strangulation courtesy of the conquistadors as argued in Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs.

La Noche Triste showed that the Mexica could defend their city

Relations between the Spanish and Mexica deteriorated soon after Cortés entered the city and decided to imprison Moctezuma. Unsurprisingly, the Mexica turned against the newcomers, especially once they learned of Moctezuma's death. The Spanish were dealt a devastating blow when they tried to flee. That attempt became known as La Noche Triste, or the Night of the Sorrows.

That night, Cortés and his men attempted to slip out of the massive city. However, according to The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico, warriors caught up with them, killing many of the foreigners. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, one of those foreigners who survived La Noche Triste, recalled that their position on a bridge was especially perilous. On one side was water, full of angry, armed warriors in canoes. On the other were rooftops, where people flung stones and other weapons at the conquistadors.

The Spanish who made it out fled to Tlaxcala, regrouped, and eventually returned to siege the city. They found a city weakened by a smallpox epidemic and unable to stand much further against the conquistadors' weaponry. With their leader gone and a vast number of people killed by disease, Tenochtitlan could not offer any more resistance. The city surrendered in August 1521. According to National Geographic, an estimated 100,000 native people were killed during the siege, compared to 100 Spanish dead.

A woman named Malintzin was key to Tenochtitlan's downfall

Malintzin, also known as La Malinche and Marina, is a deeply complicated figure in Mexican history. Without her help as a translator, Cortés and the rest of the Spanish expedition would have failed. Is she a hero, a villain, or someone in between?

An article in Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies says that she was born the daughter of a chief. When her father died, she was sold into slavery and ended up in Tabasco, near the Gulf Coast. In 1519, she was given to Cortés as part of a peace offering. Malintzin quickly showed an aptitude for learning languages, becoming an invaluable translator. She survived the siege of Tenochtitlan, treks across the jungle, and the labor of bearing Cortés' children, according to NPR. Yet Cortés couldn't even be bothered to name her in his letter to Charles V of Spain. Instead, he refers to her only as "an Indian woman."

Malintzin's help meant that Cortés could communicate and conquer more easily, but was she really free to make her own decisions? Some, like Candelaria, argue that she has been treated rather poorly throughout history. Can someone be a villain if they are trapped in a system requiring their subservience? And how did she feel about her society anyway, given her experiences as a slave before Cortés arrived? We will never know, since she didn't leave a first-hand account of her life. Whatever her true views, Tenochtitlan may not have fallen if she wasn't there.

Codices saved disappearing history

Despite the downfall of Tenochtitlan and the suppression of their culture, indigenous people weren't about to give up their history. That doesn't mean the newcomers didn't try their hardest to steamroll native culture into oblivion. In the encomienda system, as described by ThoughtCo., Spanish nobles were given previously native-held land to rule over like feudal lords. The Mexica were pushed down to the lower strata of society as Tenochtitlan metamorphosed into Mexico City. Meanwhile, smallpox and another disease, cocoliztli, kept devastating native communities.

Resistance still happened, in ways both obvious and subtle. All of those churches built on top of sacred sites led to a remix of native and Catholic religious belief, according to The Daily Beast. Meanwhile, many young people grew up with priests teaching them in the Spanish language, which they used to preserve their history.

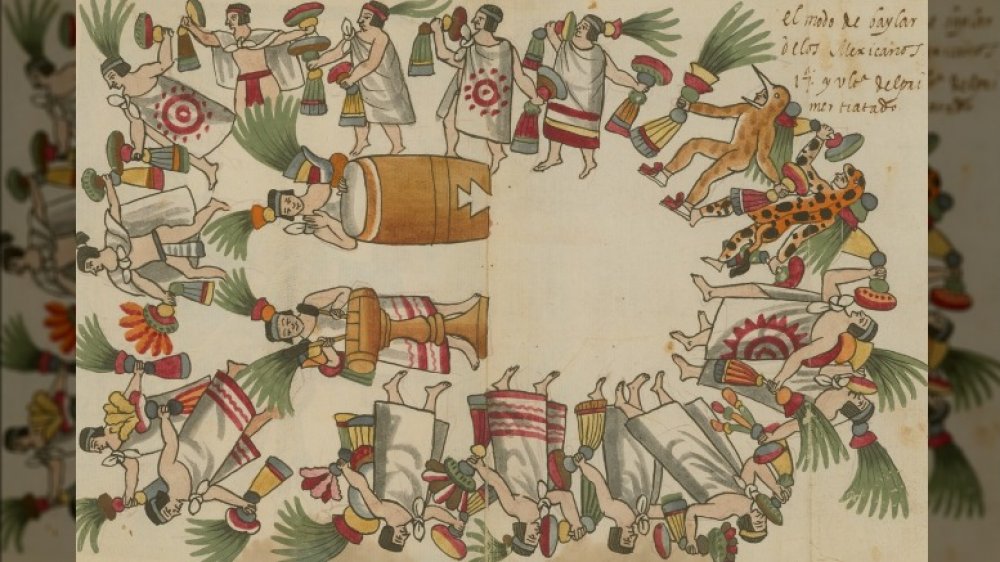

That's where we get the codices, colorful records of Aztec life densely packed with information about a fading history and culture. Many, like the Codex Mendoza described in City of Sacrifice, were produced with the support of Spanish nobles. They used Spanish spelling systems to put Nahuatl in writing that could be understood by later generations. Thanks to the scholars who created and cared for them, many are still around.

Tenochtitlan still has much to reveal

After the death of Moctezuma II and the fall of Tenochtitlan, the Spanish invaders quickly set about changing things. Many buildings were demolished to make way for European style structures, while the city itself grew to eventually fill the lake. Native culture was deeply impacted by all the forced change, but the Spanish weren't entirely successful in paving it all over.

Some structures, like the Templo Mayor, were halfway saved because previous rulers couldn't help redecorating. Every time a new ruler revamped the temple, the old structure was partially covered and protected by the new one. So, the Spanish demolished the latest version to install a cathedral, but then inadvertently preserved all of the other structures beneath.

As explained by Archaeology magazine, archaeologists and historians are still busy excavating Tenochtitlan's remains in the middle of Mexico City. They've found evidence not just of the Templo Mayor, but of everyday life in the city, from agricultural plots to family homes. The story of Tenochtitlan is still very much alive, thanks to the codices, archaeological remains, and living descendants who are still working to learn more about this world-class city and its people.