The Crazy True Story Of The Haitian Revolution

For roughly as long as there have been slaves, there have been slave revolts. On the gauge of success, the needle has generally oscillated between "total disaster" and "gave The Man something to think about," thanks to the unfortunate fact that oppressors don't generally get where they are by being bad at oppressing.

At the turn of the 19th century, however, slaves in the French colonies in Haiti pulled off an unprecedented feat, beating back the armies of the world's most powerful empires and taking a nation for themselves. This new country would be theirs and theirs alone, and there would be no more slavery. Theoretically. It's complicated.

The story, like many of the worst chapters of world history, starts with Christopher Columbus. While sailing the ocean blue in or around the year 1492, Columbus's men founded the settlement of La Navidad in northern Hispaniola. Two centuries of requisite bloodshed, smallpox, and enslavement later, the island was split into two territories: the eastern two-thirds was owned by the Spanish, while the West, aka modern-day Haiti, went to the French. French colonists set up a series of coffee and sugar plantations, and the island soon became France's most productive colony.

Haiti: a historically tough place to be

Of course, it was all thanks to a brutal culture of enslavement. According to sociologist Arthur Stinchcombe, workers were constantly being shipped in from Africa thanks to the colony's exceptionally high slave mortality rate. Britannica reports that by 1789, slaves outnumbered colonists on the island by more than 10 to 1.

In August of 1791, fueled by centuries of abuse and the ideals of freedom for the oppressed leaking in from the French Revolution, the slaves began to revolt. Former slave and general on the rise Toussaint Louverture became the movement's figurehead, conquering the island's major settlements and proclaiming himself "governor-general for life." In 1801, Napoleon sent a contingent of warships to the island to restore French rule and captured Louverture, but their forces were hoisted by their own colonial petard when an epidemic of yellow fever tore through their ranks.

By the end of 1803, France was fighting wars on every front, and its presence in the Americas was an expenditure that the empire couldn't afford. It's been speculated that the losing battle being fought in Haiti may have even been what convinced Napoleon to go through with the Louisiana Purchase. French troops were pulled from the area, and the Haitian Revolution came to an end.

Epilogue:

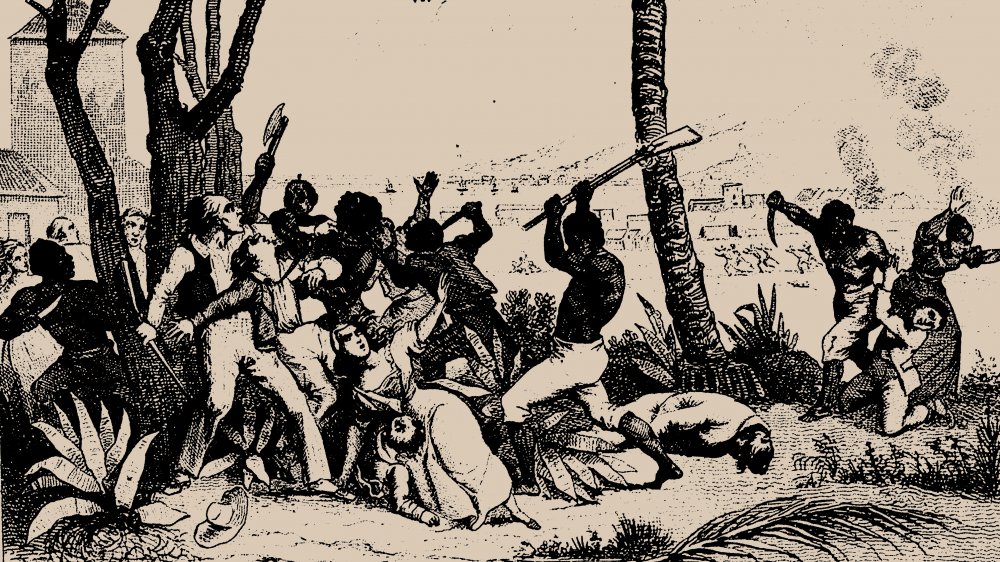

On January 1st, 1804, Haiti was declared an independent nation, the first in history created solely by the revolt of former slaves. The results were far from utopian. The 1804 Haiti massacre saw thousands of French colonists systematically slaughtered by the new Haitian government, with the country's leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines traveling from settlement to settlement and ensuring that remaining Europeans were put to death en masse. According to Brown University's History of Haiti, his rallying cry was "Koupe tèt, brule kay," or "Cut their heads, burn their houses."

A constitution was drawn up, declaring that all Haitians were Black, and that slavery was theoretically abolished. The truth is murkier — James Leyburn's The Haitian People outlines a history of blurred definitions. Serfdom replaced slavery, and when whips were outlawed as a symbol of colonial oppression, workers were struck with vines instead. As the war torn country struggled to rebuild, its reputation as the hot spot for slaves chopping up Europeans landed it with a heavy economic stigma, and development of Haiti was hampered further by reparations paid to France in exchange for their recognition of Haitian independence. Stories of unspeakable horrors carried out against whites would be used in anti-abolitionist Confederate arguments leading up to the American Civil War. Further conflicts and economic strife would continue to plague the island for centuries.

History is complicated.