What Solomon Northup's 12 Years As A Slave Were Really Like

In the mid-1800s, slave narratives were a portal into the human cost of American slavery. Between 1750 and 1865, historians believe that about 100 slave narratives were published. These stories revealed just how indefensible the institution that laws still upheld was. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 had afforded pro-slavery states controversial loopholes: If someone was declared a fugitive slave, all that was needed to establish proof was an affidavit by the claimant, according to The Guardian. In other words, during the antebellum period, enslaved Black people had no legal recourse, and those who aided their flight to freedom were also subject to prejudicial laws.

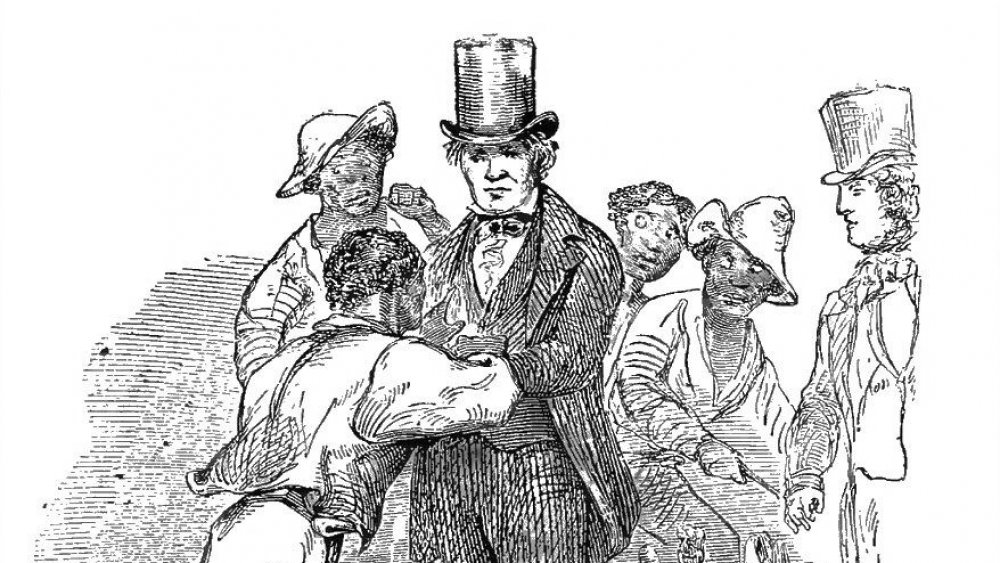

It was in this climate that the free man Solomon Northup lived in bondage and, once free again, wrote his illuminating 1853 memoir Twelve Years a Slave. Northup's tale is wholly unique because his account of slavery was from the lens of a free man. Northup was educated and skilled and had a wife and children before he was stolen and forced into 12 years of heinous brutality and labor. It is said that Harriet Beacher Stowe, author of the popular Uncle Tom's Cabin, used the New York Times' descriptions of Northup as inspiration. Here is what Solomon Northup's 12 years as a slave were really like.

Solomon Northup was born free

Solomon Northup was born a free man in Minerva, New York, in 1808. Northup was the son of Mintus Northup, who had been formerly enslaved but was freed by a member of the Northup family. Solomon Northup described his mother as mixed, and she was also free, ensuring his own freedom. While Solomon was young, Mintus Northup encouraged him and his brother to gain a high level of education and work the family farm.

Solomon Northup married his wife, Anne, in 1828, and they had three children, Elizabeth, Margaret, and Alonzo. Later on, he moved to Saratoga Springs, New York. Northup was a jack of all trades, doing railroad constriction as well as working within Saratoga Springs' hotel culture as a violinist while his wife cooked, per Saratoga.com. However, the town's economy ran on a tourism schedule, making winters tougher than summers for the Northup family. It wasn't unusual for Solomon and Anne to take jobs in neighboring communities, like Sandy Hill, to make ends meet.

Solomon Northup was drugged and kidnapped

At age 32, while searching for work in Saratoga Springs on the corner of Broadway and Congress Streets, Solomon Northup encountered two white men, whom he later identified as Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton (though their names might have actually been Alexander Merrill and Joseph Russell, per History). The pair said they were part of a circus company traveling down to Washington DC.

Merrill and Russell offered to hire Northup as a fiddler in their company for a show in New York City, and Northup accepted their touring offer without so much as sending word to his wife. In New York, the pair of kidnappers suggested Northup register for his free papers to have on hand. Of course, that was a ruse. The tour kept extending, and as the circus performers arrived in Washington DC, where slavery was still legal in 1841, Merrill and Russell made their move. With President William Henry Harrison's funeral overwhelming the entire DC area, they suggested an extended stay. On a night out drinking, they drugged Solomon Northup, making him outrageously ill. In his hallucinatory state, Northup was brought to a second location. He did not have his belongings, his free papers, or any form of identifying himself. "It could not be that a free citizen of New-York, who had wronged no man, nor violated any law, should be dealt with thus inhumanly," Northup wrote in his memoir.

Solomon Northup's journey South

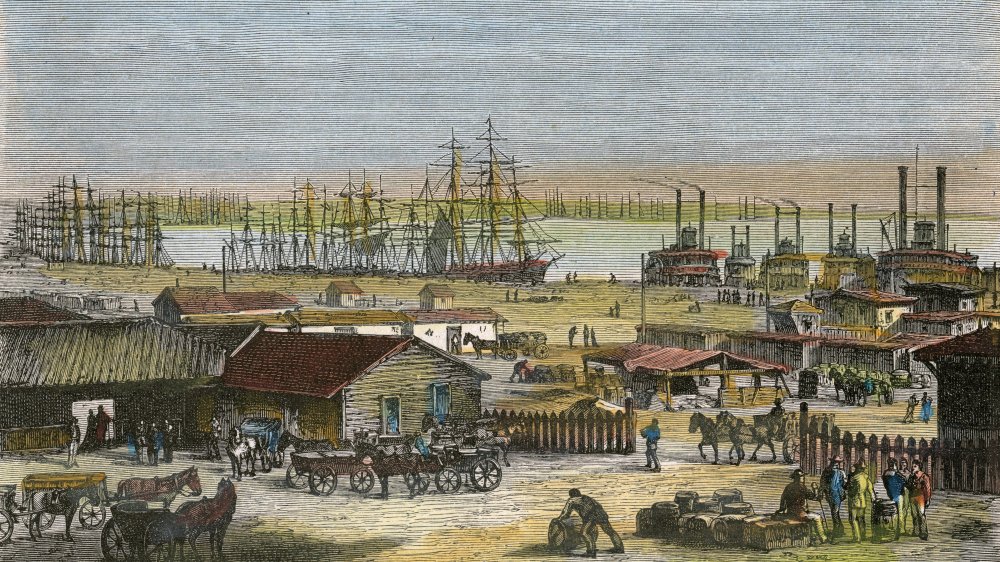

Solomon Northup woke up chained in Washington DC in what was known as Williams' Slave Pen. This pen, located mere blocks from today's Capitol, was run by the slave trader James H. Burch and his turnkey Ebenezer Radburn. Northup initially insisted on his free status but was brutally beaten with a paddle by his jailors until he ceased to mention it. Other kidnapped and enslaved men and women were locked with Northup, including a woman named Eliza and her two children. The group was brought to Richmond, Virginia, where they boarded a ship headed for New Orleans, Louisiana.

On the ship, there was limited space and barely any food, and a smallpox outbreak caused the death of one enslaved passenger named Robert. Days before Solomon Northup expected the ship to dock, he risked asking a sailor, John Manning, if he would bring him a pen and paper to write a letter to his family about his kidnapping. Manning agreed and aided Northup. This letter actually made it to New York, and although Henry B. Northup received it and brought it to Governor Seward, nothing was done about it because they didn't have Solomon Northup's precise location in Louisiana. This was at a time that the state of Louisiana had civil codes on the books such as "The slave is entirely subject to the will of his master," according to Accessible Archives.

Solomon Northup lost his identity

In New Orleans, Solomon Northup was put on auction by a man named Theophilus Freeman. Freeman, reading from a roll call, insisted that Northup must be called "Platt." From that point on, Northup's true identity was concealed, and he was only ever addressed as "Platt" for the next 12 years.

Before the auction, Northup and many aboard the ship contracted smallpox and were hospitalized, as records confirm. When the enslaved men and women were cured of their near-fatal illness, Northup witnessed the horrific separation of Eliza and her two children, who had been sold to different enslavers. "Never have I seen such an exhibition of intense, unmeasured, and unbounded grief," Solomon Northup recounted in his book.

Northup was then purchased by a man named William Ford and taken to the Red River region of Louisiana. Northup described the intensely Christian Willam Ford as a "model master" — one who avoided unwarranted beatings, who read scripture to those he enslaved each Sunday, and offered praise for his carpentry. It is this particularly generous characterization of Ford that was striking to readers of Northup's memoir. Northup was describing an institution in which not every enslaver was irrevocably evil: "It is not the fault of the slaveholder that he is cruel, so much as it is the fault of the system under which he lives," Northup maintained. However, Northup was only enslaved by Ford for about a year.

Solomon Northup's cruel enslavers

Solomon Northup's fate was changed when William Ford, owing much debt, sold off 18 of his enslaved workers. Northup was sold to John Tibeats, a cruel and petty carpenter, in the winter of 1842. However, as reported by Britannica, Ford still held 40-percent ownership of Northup, as he was deemed to be "worth" more than the debt.

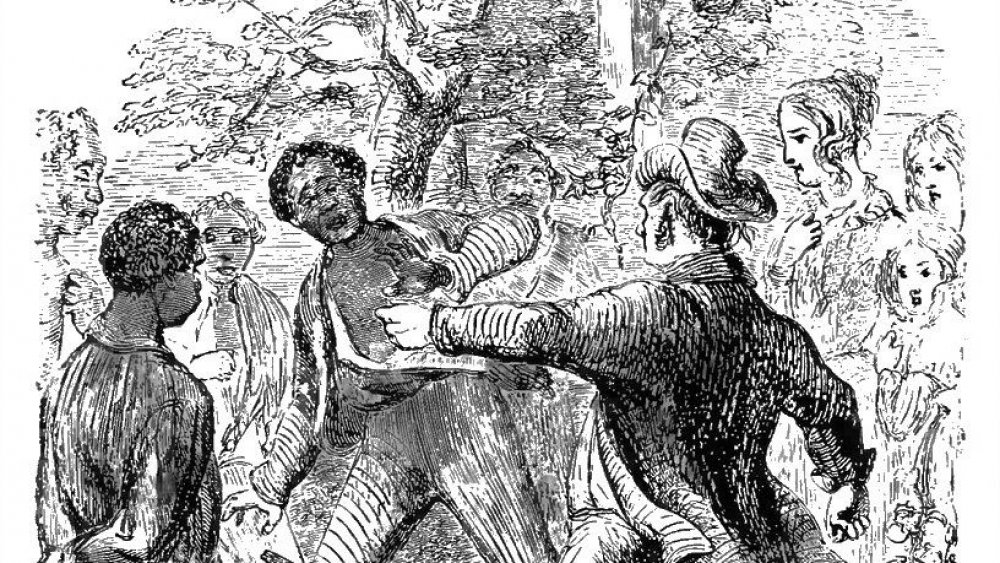

John Tibeats (who was likely named John Tibaut) was an especially cruel man. Tibeats, in an altercation about nails at a construction site, tried to whip Northup, but Northup physically restrained him and stepped on his neck, something almost unheard-of for an enslaved person. In retaliation, Tibeats, along with some local enslavers, attempted to lynch Solomon Northup and tied a noose around his neck and bound his limbs. As they looked for a tree from which to hang Northup, Chapin, the field overseer, walked up carrying a pistol in each hand. Chapin reminded John Tibeats that he would owe Ford a mortgage if Northup was murdered.

Tibeats fled the scene, leaving Northup bound under the hot sun for hours. "During the whole long day I came not to the conclusion, even once, that the southern slave, fed, clothed, whipped and protected by his master, is happier than the free colored citizen of the North. To that conclusion I have never since arrived," Northup said of the horrifying torture. It was only after Ford arrived at the plantation that Solomon Northup was let free from his noose.

Solomon Northup attempted to escape

Solomon Northup remained enslaved by John Tibeats. During another tempestuous criticism of Northup's forced labor, Tibeats seized a hatchet. Northup, fearing for his life, fled to the surrounding swamps to escape. However, Tibeats got a horse and hired bloodhounds to chase Northup. Solomon Northup evaded capture and spent the evening wading through the Great Pacoudrie Swamp, dodging alligators, snakes, and capture. By daybreak, Northup realized he could not flee forever, as this was Louisiana, and he was without his papers identifying him as free. At the time, enslaved individuals were not allowed to travel without a pass. The pass was important: "Catching runaways is sometimes a money-making business. If, after advertising, no owner appears, they may be sold to the highest bidder; and certain fees are allowed the finder for his services, at all events, even if reclaimed," as Northup wrote.

Northup, desperate for sanctuary, returned to William Ford's plantation, where Ford allowed him to nurse back to health. But Ford returned Northup to Tibeats with a warning that Tibeats should sell Northup off or risk another runaway situation. It was from this abusive situation that Solomon Northup passed into his next.

Daily life on a cotton plantation

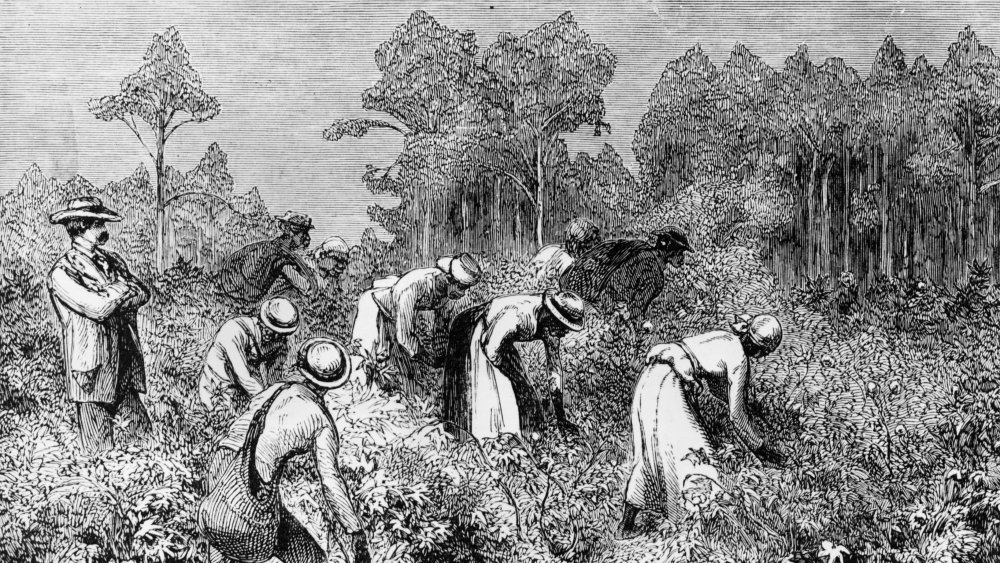

From Tibeats, Solomon Northup was sold to Edwin Epps, who he was enslaved by for the next ten years. A cruel man who whipped those he enslaved for fun, Epps required a particularly grueling workday on his cotton and sugar plantations. Food was scarce — Northup was given three and a half pounds of bacon and some cornmeal for the week and forced to hunt for possums if he ran out. Enslaved workers were in the fields by daybreak, had merely ten minutes for lunch, and worked until dark, where they then weighed their output. According to Northup, enslaved workers were fearful of their daily weigh-ins: If they'd picked too much cotton, they'd be expected to pick more. If the enslaved workers hadn't picked enough cotton, they would be whipped.

The enslaved men and women on Epps' plantation were given three days off a year at Christmas. On this "vacation" and some evenings, Northup was hired out to play violin for local plantation families.

The idea of freedom was never far from Solomon Northup's mind. Northup's literacy was an advantage — a fact he kept hidden from his enslavers, as noted by ThoughtCo. He looked for opportunities to write, stealing a sheet of paper from Mrs. Epps. By boiling white maple bark and plucking a feather from a duck, Northup fashioned ink and a pen. He waited patiently for a time to send a letter, but he never found a trustworthy white person to deliver it.

The torture of a friend

Solomon Northup was made the driver of the other enslaved men and women on Edwin Epps' plantation, a position he took against his will. Asked to whip others if they weren't working speedily, Northup mastered giving out lashes that were just a few centimeters from people's bodies so that they didn't actually inflict pain. Patsey, a friend of Northrup's, was frequently a victim of the whip. Patsey was a terrifically talented field worker, strong, and dexterous. Tragically, she was also regularly raped by Edwin Epps and would afterward endure the beatings and vitriol of Epps' jealous wife.

In one of the most harrowing events of Northup's enslavement, sometime in the late 1840s, Patsey went to a neighboring plantation to get soap — which Mrs. Epps denied her — and returned to find Epps incredulous. Epps made Northup strip Patsey and tied each of her limbs to a stake in the ground. Acting as his proxy, Northup was forced to horrifically beat his friend Patsey. When Northup could not go on, Epps proceeded with her beating. Patsey, flayed after hundreds of lashes, was near death.

There is no historical record of what happened to Patsey between 1853 and emancipation, but it is likely she endured such abuse from the Epps family for years to come, according to Vanity Fair. "The institution that tolerates such wrong and inhumanity as I have witnessed, is a cruel, unjust, and barbarous one," Solomon Northup wrote.

Solomon Northup meets Bass

In 1852, a Canadian abolitionist carpenter named Samuel Bass came to work with Solomon Northup, constructing a new house for Epps. A rarity in the antebellum South, Bass was unafraid of criticizing slavery and would often engage in debates about it with Edwin Epps. As Northup recalled, one day Bass argued: "If they don't know as much as their masters, whose fault is it? They are not allowed to know anything. You have books and papers, and can go where you please, and gather intelligence in a thousand ways. But your slaves have no privileges."

Solomon Northup, sensing he could trust Bass, impressed him with his knowledge of Canada and Northern geography. Finally, Northup explained that his name was not "Platt" and that he was born a free man in New York. Bass, sympathetic with Northup, agreed to deliver a letter to the post office for him. When, after months, no reply came, Bass returned to Epps' plantation to inform Northup that he would go to Saratoga Springs himself in a few months to get help. Bass' aiding Solomon Northup was an act that risked his own life at the time, per The Guardian. Miraculously, the letter did reach New York.

Solomon Northup's rescue from bondage

Solomon Northup's rescue took shape. William Perry and Cephas Parker of Saratoga Springs, New York, received the letter and forwarded it to Anne Northup. She then sent it to Henry B. Northup, a lawyer and the grandnephew of Solomon Northup's father's former enslaver. Luckily, there were grounds for his release. There was an 1840 statute allowing the rescue of New York citizens sold into slavery, per Britannica. Henry B. Northup petitioned the governor of New York, Washington Hunt, for help and secured free papers for Solomon. According to ThoughtCo, after a stop in Washington and a visit with the Louisiana senator, Henry then traveled to New Orleans, making his way to Epps' plantation in January 1853.

There was one major snag in the rescue effort: Henry was searching for Solomon Northup, but local enslavers and the Louisiana government only knew him by the name of "Platt." The lawyer managed to track down Samuel Bass, who directed him to Epps' plantation, where finally, Henry was able to free Solomon after confirming his identity with a series of personal questions.

Solomon Northup was again a free man after 12 heartbreaking years of near-starvation and hard labor. However, the occasion was not without its bitter note. The men and women Northup had labored beside for a decade remained enslaved. As Solomon Northup left the plantation, Patsey and others mournfully asked him, "What'll become of me?"

Solomon Northup's trial

Before heading home, Henry B. Northup and Solomon Northup made a stop in Washington DC to prosecute the slave trader responsible for his 12 years in bondage.

However, there were many legal impediments to Solomon Northup's 1853 case. First, Washington DC law prohibited Black witnesses from testifying against white people, leaving Northup banned from taking the stand. A January 20 New York Times article also pointed to Louisiana laws, like a statute of limitations on prosecuting someone illegally selling slaves or buying slaves without knowing their true legal status, per Smithsonian Magazine. Those laws nullified Solomon Northup's ability to find justice. When James H. Burch, the slave trader in DC, testified, he spun a preposterous lie: Burch accused Solomon Northup of colluding with his kidnappers on a get-rich-quick scheme, as reported by The Guardian. All charges were acquitted.

It wasn't until January 21, 1853, that Solomon Northup arrived at his home in Sandy Hill, where his wife and children greeted him with overwhelming relief. But Northup had another chance at justice in 1854, when a New York judge, Thaddeus St. John, identified Alexander Merrill and Joseph Russell as Northup's kidnappers. St. John had seen the pair in the company of Northup on the way to DC. in 1841, but on their return, he observed them again, this time with new clothes, canes, and watches, per History. However, after two years of appeals, the charges were dropped. The system failed Solomon Northup.

After Northup's 12 years as a slave

Within months of his release, Solomon Northup set to work on a memoir, calling on lawyer and author David Wilson to help him translate his life to a book. The memoir, Twelve Years a Slave, sold 30,000 copies in three years, according to History. Despite its success, Northup earned only $3,000.

After the print of his book, Solomon Northup did a lecture circuit of his life story and produced two stage plays about his experience, and according to NPR, there's evidence that he might have aided the Underground Railroad. After that, Northup lived the rest of his life in relative obscurity, with the last known mention of him being in an 1857 Canadian newspaper. It is not known when or how he died — his grave cannot be located.

Solomon Northup's narrative might never have been heard by a contemporary audience if it weren't for the work of Louisiana historian Sue Eakin, who, in 1968, co-edited a new edition of the memoir. Eakin tracked down records to confirm Northup's story — from the Lousiaian ship's manifest to hospital records, as told by the BBC. A 2013 film of Solomon Northup's life, Twelve Years a Slave, directed by Steve McQueen, renewed interest in his story. Solomon Northup's story was the rarest of slave narratives and one that deserved to be seen as more than anti-slavery propaganda. Twelve Years a Slave is a fact-checked view of the United States' most horrifying institution.