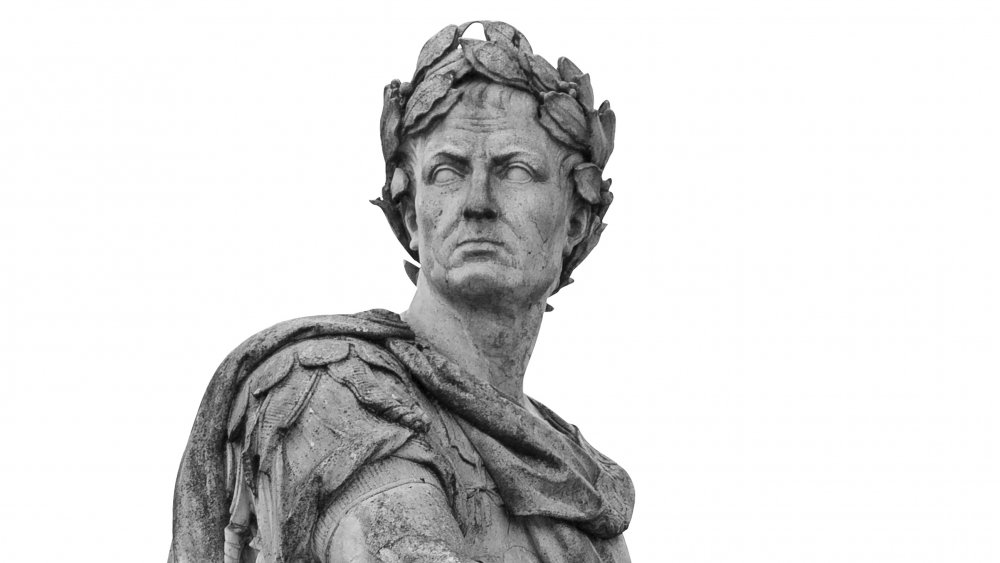

How A Volcano May Have Led To The Rise Of The Roman Empire

I have long been sated with power and glory; but, should anything happen to me, Rome will enjoy no peace.," as UNRV.com translates Suetonius's quotation of Julius Caesar. "A new Civil War will break out under far worse conditions than the last." Then, on March 15 44 BCE, Julius Caesar fell assassinated before the daggers of the Roman Senate.

With his death, the Senate thought that the unrest that had defined the last half century and last fifty years in particular would end. The last of the Triumvirate had fallen, so they could start again.

However, they were wrong. Virgil, a contemporary epic poet, would later write how "[The sun] and no other was moved to pity Rome on the day that Caesar died, when he veiled his radiance in gloom and darkness, and a godless age feared everlasting night." Nor was this mere poetical embellishment. The biographer Plutarch wrote that "the sun's rays were veiled. Throughout the year, it's orb rose pale and without radiance, while the heat from it was slight and ineffectual... and fruit remained [on the trees] imperfect and half-ripe, and withered away and shriveled up due to the coldness of the atmosphere."

The consequences of such phenomena extended beyond the pathetic fallacy however. Due to the lack of sunlight and unseasonal temperatures, the army of the conspirators faltered in the Greek countryside, allowing Mark Antony to defeat them and Augustus to direct the Republic to the Empire.

The disrupting eruption

Now, we don't believe that the ball of gas burning billions of miles away had any feelings for Julius Caesar one way or the other. However, a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests a coincidental explosion at Mount Okmok, a volcano in Alaska, caused the extreme climate that decided the very end of the Republic and birth of the Empire. Evidence from ice cores and tree rings indicate that 43 BCE, the year Okmok erupted, was the second coldest in the last 2,500 years with an average 13-degree Fahrenheit drop across southern Europe and northern Africa, the extent of the Roman Republic at the time.

But, as Smithsonian Magazine details, there is still some disagreement about the idea, with critiques ranging using this one event to exaggerate all cooling effects to conflating natural issues with political. Guy Middleton, an archaeologist at Charles University, dislikes the emphasis placed on the eruption itself: "The problems with the republic were political, deep in origin, fought out between members of the elite, not a popular revolution or a subsistence crisis." The extensions between elites throbbed long before and for a good decade afterwards.

Even one of the study's co-writers, John Manning at Yale University, agrees: "It's not 'a volcano erupts and a society goes to hell." But, examining history through this lens could help us understand better both then and our climate changing present.