The Untold Truth Of The Navajo Nation

The Diné, also known as the Navajo Nation, have a long history on the North American continent. Despite continued threats of obliteration from Spanish and American colonizers, the Diné resisted for centuries, fighting for their lives and their culture.

The Navajo Nation has over 300,000 enrolled members, making it the second-largest Native nation in the United States, after the Cherokee Nation. While many Diné currently live on the reservation, the historical road to that reservation was paved with suffering.

After countless abuses and treaty violations over the years, in 2014, the United States agreed to pay the Navajo Nation a settlement of $554 million for the county's mismanagement of both natural resources and funds. But this number doesn't come close to accounting for the damage that the Diné people suffered and continue to suffer at the hands of the US government. This is the untold truth of the Navajo Nation.

The Navajo Nation's northwestern origins

While the Diné currently live in the southwestern United States, their origins extend up the North American continent. According to An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States by historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, while the majority of the Diné people remained in northwestern Canada, some migrated from the subarctic to the present-day Four Corners region.

Archaeological research suggests that the Diné had reached the Southwest by the 1100s, if not earlier. When linguists began classifying Native North American languages, they discovered that the Diné and Apache languages bear a striking resemblance to the Athabaskan language family, not only in vocabulary but in grammatical structure as well. The orthography was standardized by William Morgan and Robert Young as recently as the 1940s.

The Diné language was notably used in World War II by the Marine Corps, when upwards of 400 Diné were tasked with transmitting messages. The Diné language was little-studied at the time, so a code was created out of Diné words which was indecipherable to the Japanese. The Code Talkers were essential in the war effort, with Major Howard Connor declaring, "Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima." Despite the crucial work of the Code Talkers, they received no public praise for their efforts until 1992.

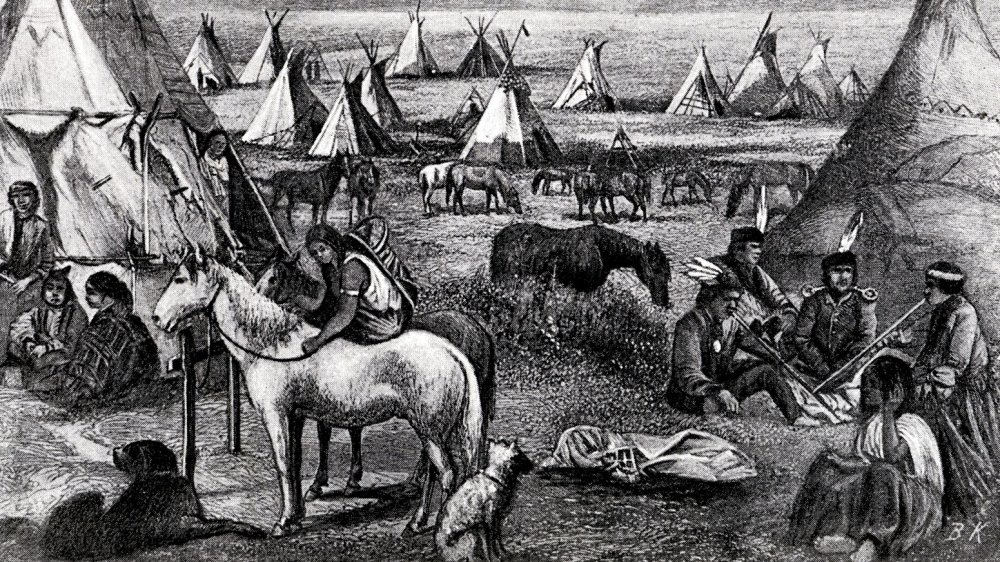

Trading and interactions of the Navajo Nation

The Native people on the North American continent created an extensive network of trade routes and roads, allowing for a great deal of movement and cultural interaction. According to A Diné History of Navajoland by Klara Kelley and Harris Francis, the trade corridor network was mapped orally by the Diné stories. In addition to hunting and foraging, in the Southwest, the Diné began farming maize, squash, and beans. Archaeological evidence shows that in addition to using the trade routes, at times, farming was concentrated in the northern Black Mesa. The networks extended far, with some Diné histories telling of hunters visiting Aztec, Chaco, and other important Anasazi locations.

When the Diné reached the Four Corners region, they began to interact and intermarry with the Pueblo people, as well as engaging in political and military alliances and conflicts. Some scholars like Peter Iverson suggest that Pueblo women were the ones who introduced the Diné to raising sheep.

According to Navajo Trading: The End of an Era by Willow Roberts Powers, the Diné were neither particularly unified nor nomadic, and their disparate groups traveled widely. Through this disunity, they covered a great deal of land and were able to trade with a wide variety of people, such as the Utes, Hualapais, Mescalero, and Yavapais.

The collective disunity of the Navajo Nation

Rather than having a centralized government, the Diné had localized leadership among a series of autonomous groups. According to Navajo Sovereignty: Understandings and Visions of the Diné People, there's no single word in the Diné language that translates to sovereignty in the Western sense. Set around a matrilineal clan, there existed a system of self-governance where leaders were chosen by consensus and worked with the people in governing using the Fundamental Laws. Participatory democracy and talking things out were integral to consensual decision-making, and the k'é principle was foundational, seeking to encourage values that promoted peace and cooperation.

These principles would guide agreements for trade, peace, and military alliances with other Native groups, the Spanish, and the United States. When the Diné were imprisoned at Bosque Redondo, before Head Chief Barboncito negotiated a treaty with General Sherman, he met beforehand with his people on May 27, 1868, and the points that were later presented to Sherman's commission were decided upon by the Diné communally.

Despite this internal unity, the Diné as a nation were a series of separate groups. While there might be occasional collaboration, more often than not, local authority prevailed.

The Navajo Nation and Spanish explorers

While the Spanish had difficulty in the 1500s telling Native groups from one another, they began to recognize commonalities among the Diné languages and rituals. In 1626, the Diné were first referred to as "Navajo" by Fray Geronimo de Zarate Salmeron, who wrote of "the Apache Indians of Navaju."

The Spanish were suspicious of the Diné's alliances with the Pueblo and frequently attacked and kidnapped the Diné people. According to Diné: A History of the Navajo, the Diné suffered more from Spanish slavery than any other Native group. Women and children were especially targeted, and according to Reclaiming Diné History by Jennifer Nez Denetdale, many people's lives were defined by being enslaved. It's estimated that upwards of 66 percent of all Diné families lost a member to slavery in the early 1800s.

The Diné would frequently carry out raids on the Spanish as reprisal and were able to withstand their assault. In 1680, they banded together with the Pueblo for the Pueblo revolt, which was a war against the Spanish, who had assaulted and terrorized the Pueblo for years. While the Spanish were driven back for a time, by 1693, they'd reconquered the Rio Grande Valley. During this time, fleeing Pueblo refugees were taken in by the Diné, resulting in further cultural intermixing.

The long walk of the Navajo Nation

Relationships between the Diné and the colonizers didn't improve when the Diné encountered the United States Army in 1846 during the Mexican-American War. Between their first interaction with the Americans in 1846 and their return to their ancestral homeland in 1868, the Diné signed nine separate treaties with the US, although only two would be ratified.

In The Navajo Political Experience, author David E. Wilkins writes about how, like the Spanish, the US government was under the impression that a treaty signed by a few Diné would apply to the entire group of people. There was no consideration given to their decentralized political structure. But ultimately, the US was more concerned with eliminating the Native people than with negotiating with them.

According to the Library of Congress, in 1863, the US Army rounded up almost 10,000 Diné and 500 Apache from what is now considered Arizona and western New Mexico and forcibly marched them at gunpoint to the Bosque Redondo Reservation. During the 18 days of marching, hundreds died from the conditions. Those who were elderly, ill, or too slow were often shot and left behind. According to NPR, this death march, known as the Long Walk, was mostly ignored by the rest of the country, which, at the time, was preoccupied with another civil war.

Imprisonment of the Navajo at Bosque Redondo

After thousands of Diné and Apache were marched over 400 miles, they reached Bosque Redondo. While the United States claimed it was a reservation, it was nothing more than a glorified prison camp, according to Smithsonian Magazine. The 40 square miles of desert and shortgrass prairie they were given was unusable for farming, and whatever crops seemed to take were soon destroyed by cutworms.

The Diné had been told they were being taken to a good place, but it was quickly apparent that this was not the case. While Native people were not allowed to leave the reservation, some were able to escape, though capture posed not only danger to oneself but also to loved ones. But some considered it worth the risk, with upwards of 1,500 people escaping from the Bosque Redondo Reservation.

While they were interned, the Diné and Apache were not allowed to practice their own traditions, since the US was hoping to assimilate them. There was a lack of clean water and little food, and living was almost completely unsustainable. Whatever food was given was foreign to the Native people's diets and would often make them sick. Shelters were incredibly crude, and diseases such as smallpox, pneumonia, and dysentery ravaged communities. Shelters were crude, and during the harsh winters, there wasn't adequate heat. In 2005, the United States opened the Bosque Redondo Memorial to acknowledge the suffering that happened there.

A partial return for the Navajo Nation

After five years of imprisonment at Bosque Redondo Reservation, the Diné signed a treaty with the United States in 1868 that allowed them to return to Dinétah, their ancestral homelands. Known as Naal Tsoos Saní ("The Old Paper") among the Diné, the document is also known as the Treaty of Bosque Redondo or The Navajo Treaty of 1868.

The treaty wasn't signed out of goodwill and was, in effect, a partial admission of defeat by the US in their attempt to remake Native people in their own image. Not only was the endeavor not working and perceived to be too harsh by some non-Native critics, but it was also considered too expensive to sustain.

The treaty also included other provisions, such as the stipulation that Native children receive compulsory education, often at government and missionary boarding schools. While the treaty established the Navajo Nation as "domestic dependent" of the US, its signing affirmed the potential of Diné sovereignty even under the oppressive rule of the United States.

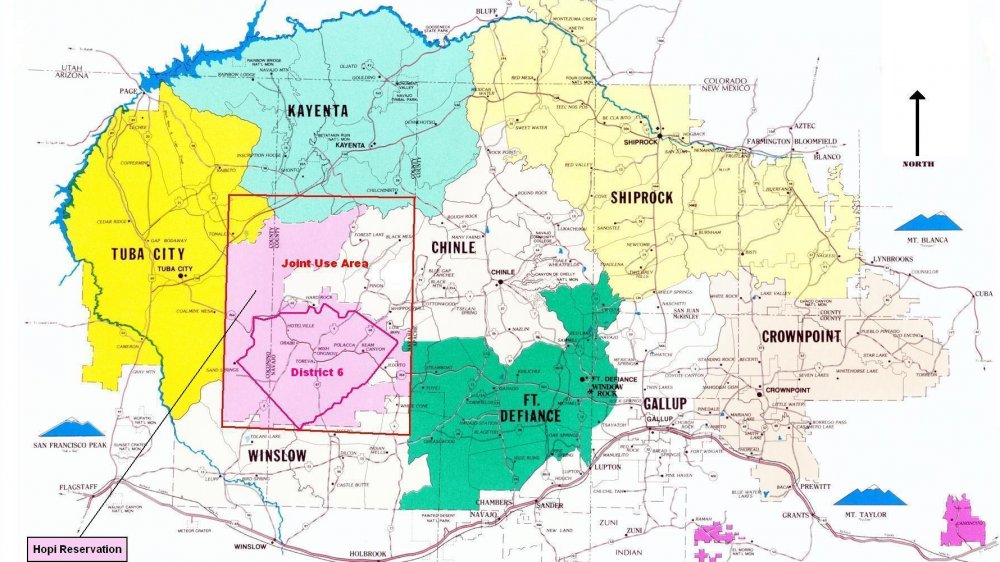

The reservation and its changing borders

Despite being able to partly return to their ancestral homelands, the Diné continued to suffer at the hands of the United States government. According to Smithsonian Magazine, while the Diné are the only Native group to reclaim their homeland through a treaty, said treaty allotted the Diné a 3.4 million-acre reservation, only about one fourth of their traditional territory. In signing the treaty, the Diné were also forced to give up their right to oppose the construction of roads, railroads, and military posts across their lands.

However, since the boundaries of the reservation were not physically defined, few Diné adhered to the borders established in the treaty. And for a brief period, congressional acts and executive orders from President Rutherford B. Hayes actually added land to the reservation in 1878 and 1880, in a sense legalizing the movement of the Diné. Despite the fact that tribal lands were decreasing, the land base was increasing.

In 1882, another executive order, this time by President Chester A. Arthur, established a reservation for the Hopi tribe in areas where the Diné already were. This led to the relocations of many Hopi and Diné people, and the right to occupy the land continues to be a point of dispute to this day.

Leasing back stolen land

In the Naal Tsoos Saní, there was a stipulation that allowed the Diné to use the land for individual farming. Although this article wasn't widely enforced, it demonstrated the United States' continued investment in dissuading Native people from their communal practices.

The article foreshadowed the Dawes Act of 1887. Also called the General Allotment Act and authored by Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, the law allowed the US to break up reservation land that was held in common by a group of people into small allotments to hand out to individuals. According to Our Documents, it was claimed that the act was meant to protect the property rights of Native people, albeit in accordance with the Western idea of property and rights. The results, however, were drastically different.

As the Diné had stolen lands leased back to them, more often than not, the land allotted would be unsuitable for farming. Any land that wasn't allotted was then deemed "surplus land" by the government and sold to non-Natives, while the land that was allotted to Natives would continue to be held in a trust by the US government for 25 years. As a result of the act, Native land holdings went from 138 million acres to 48 million acres by 1934, and land leases continue to be an issue to this day. The unsuitable conditions of the reservations themselves wouldn't be addressed until the Meriam Report of 1928.

The first Navajo Nation Council and centralization of government

The Navajo Nation Council was originally created by the United States government so that American oil companies could have someone to negotiate with. According to the Diné Policy Institute, once oil was discovered on treaty lands in 1922, the federal government decided that they needed a semblance of central authority to interact with in order to lease the land and access the resources — the decentralized nature of the Diné's governance was a threat to their potential profit margins. The creation of the Navajo Nation Council essentially eliminated the distinction between executive-order lands and treaty lands, which had previously kept land leasing at bay.

Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall and Bureau of Indian Affairs commissioner Charles H. Burke planned a representative-style, centralized government and brought their plan to the Diné. They knew that they needed the appearance of democracy, and after the Diné voted for 24 delegates, the delegates chose a chairman who promptly gave negotiating powers to Herbert Hagerman, the New Mexican politician who'd been initially selected by Fall and Burke to be the special commissioner for negotiations with Native people. After the first meeting, a resolution by the BIA gave Hagerman the power to "sign whatever oil leases he wished on behalf of the Navajo Indians."

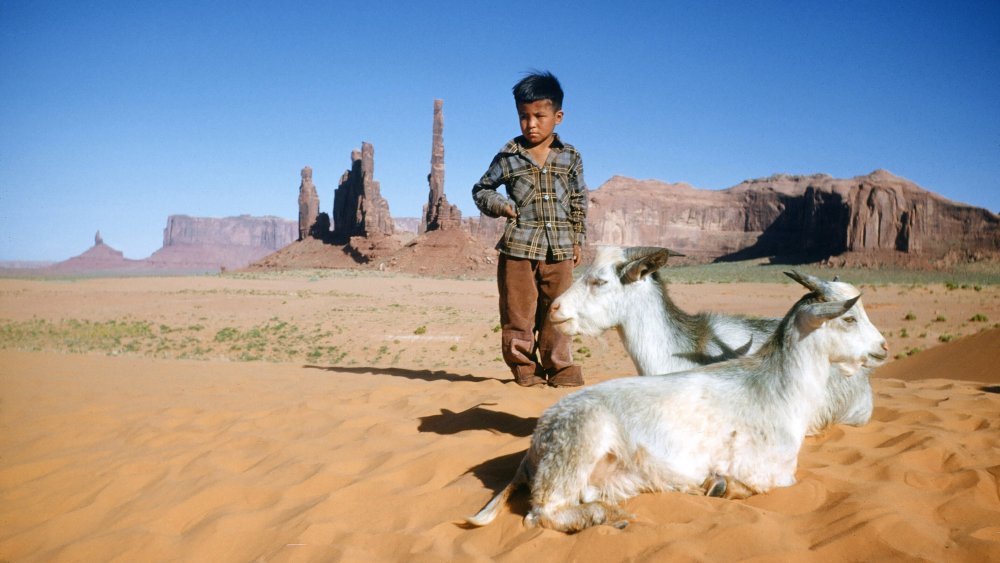

Livestock reduction act

In 1930, a forester for the Bureau of Indian Affairs named William Zeh submitted a report that remarked on overgrazing by the Diné's livestock. With fewer than 12 million acres of land trying to sustain roughly 1.3 million sheep and goats (horses and cattle not included), the land was being damaged. Zeh primarily recommended an expansion of the reservation and improving the breeds of sheep, with a gradual reduction in the number of goats.

Despite the fact that the winters of 1931-1932 and 1932-1933 had led to the starvation of numerous sheep and goats, the United States decided that the Diné had to further decrease their number of livestock. According to the Southwest Indian Relief Council, the BIA met with Diné men to let them know how many sheep they'd be allowed on their land, despite the fact that sheep were maintained by Diné women.

Initially, the government reimbursed the Diné for the livestock that they slaughtered, though the compensation was often less than fair, with one family bringing 180 horses and receiving only $2.50 a head for 80. As time went on, animals would simply be shot and left. Active reduction lasted from 1933 to 1946 and reduced the number of sheep from 1,053,498 to 449,000. This disrupted the income and livelihoods of thousands of people, and these policies remain in what are today known as grazing regulations, which continue to mandate livestock numbers.

The Navajo Nation and uranium

From the 1940s to the 1980s, almost 30 millions of tons of uranium ore were extracted from the lands of the Navajo Nation. The Diné were used as workers while being offered no protection from the radiation and being provided with no information about its dangers. Hundreds of Diné worked near or in the uranium mines, and many lived near the mines and ore mills.

According to Rafael Moure-Eraso, former chairman and chief executive of the US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, the Atomic Energy Commission and the Public Health Service not only knew and failed to protect miners from the dangers of radiation, but they conducted observational studies on the miners without their consent. It's on record that the PHS decided that "the individual miners would not be told of possible potential hazards from radiation in the mines for fear that many miners would quit and others would be difficult to secure because of fear of cancer."

According to NPR, the United States only started cleaning up in recent years. And while the mining ceased decades ago, the Associated Press reports that about a quarter of Diné women and infants suffer from high levels of uranium in their system. In 2017, a $600 million settlement was reached to help clean up some of the mines.

The Navajo Nation today

After years of continued oppression by the United States, struggling against lack of running water, lack of housing, and unemployment, the Navajo Nation is now battling the US government's mismanagement of the coronavirus pandemic. Lack of clean water has historically been an issue for the Diné's reservation, making it even harder to fight the pandemic. Nearly one out of three families don't have running water or electricity, and there are only 13 grocery stores in the entire reservation. Many areas also have an emergency room but no hospital, which means that people might have to travel over 100 miles to receive care.

The rate of infection due to COVID-19 is a shockingly high 3,739 per 100,000. According to Al Jazeera, Diné leaders have increased restrictions and are criticizing the lack of a wider effort to contain the virus, such as Navajo Nation president Jonathan Nez disparaging the pace of the federal government's response.

Despite the lack of federal support and internal infrastructure to fight the virus, many young Dine are coming together to provide assistance to their elders and families, putting themselves in danger so that more people don't get sick.