The Messed Up Story Of The 1992 L.A. Riots

Without a doubt, the five days of rioting experienced by Los Angeles in the spring of 1992 rank high as one of the most racially volatile moments in post-Civil War America. After a jury essentially exonerated four Los Angeles policemen accused of using excessive force on an African-American motorist, Rodney King, the city erupted into the costliest urban civil disturbance in American history.

Los Angeles hadn't seen anything like it since the summer of 1965, when racially charged unrest broke out in the community of Watts. What happened in LA in 1992 deepened America's racial divide and exposed the faults of a criminal justice system that hasn't always been fair to African-Americans, and the riots are just as relevant today as they were 28 years ago. The saga of the Rodney King trial and the ensuing riots began with a grainy home video that sent shock waves around the world.

The Rodney King beating started it all

On March 3, 1991, when plumbing contractor George Holliday stood on the balcony of his LA apartment filming Rodney King's savage beating, he had no idea that he was capturing what would become the most famous home video since the Zapruder film, according to film critic Peter Bradshaw. As reported by The Washington Post, Holliday captured four LA cops striking Rodney King 56 times with batons while at least a dozen others stood by watching. King was jolted with a stun gun charged with 50,000 volts of electricity. The beating was so bad that one of the cops said that he hadn't "beaten anyone this bad in a long time."

Before the beating, King had been speeding down a freeway when police officers tried to initiate a traffic stop, but King refused. He was afraid of getting sent back to prison for violating his parole for a robbery conviction. King led the police on a high-speed chase that ended across from Holliday's apartment building.

Later, Holliday took the footage to a local television news station. It made the rounds on TV in America and around the world. For African-Americans, the recording was hard proof of the police brutality that they had long complained about. King was reportedly left with several lacerations, a broken cheekbone, broken teeth, an injured leg, skull fractures, and permanent brain damage.

The verdict that led to the LA riots

A jury of 12 people — nine white, one biracial, one Latino, and one Asian — sat for the trial of the four police officers charged with using excessive force on Rodney King. From the beginning, racial demographics played a role in the highly publicized state trial, which was taken out of Los Angeles to a nearly all-white suburb in Ventura County. A Los Angeles Times poll showed that most LA residents believed the cops were guilty.

After listening to testimonies for seven weeks and watching Holliday's tape more than 30 times, the jurors decided that King had committed a lot of errors. One juror told the Los Angeles Times that "he refused to get out the car" and was uncooperative and went on to say that King was "obviously a dangerous person" and that the police had no choice, even though a witness testified that King never resisted and was compliant with the cops.

The jury also doubted the severity of King's bruises. According to ABC News, one juror thought that the police beating looked bad, but didn't seem to be against the law. The defense, meanwhile played up a narrative that the cops had a duty to protect themselves and the community. After seven days of deliberation, on April 29, 1992, the jurors found the four officers not guilty of using excessive force. UCLA law professor Jody David Armour said his "jaw dropped" when he heard the verdict.

No justice, no peace

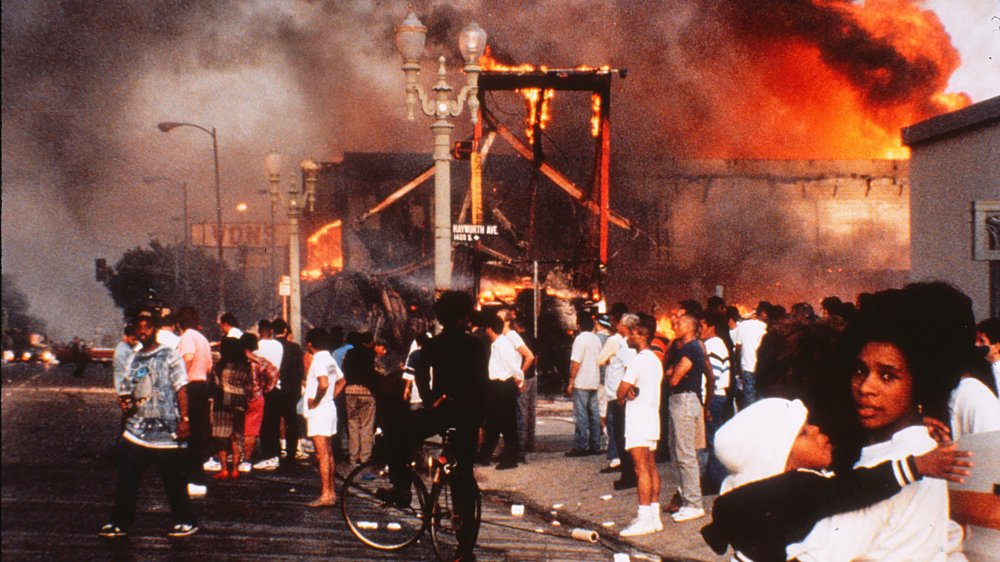

About an hour later, 300 protesters gathered in front of the courthouse to cry foul. LA mayor Tom Bradley, a former police officer himself, said the cops involved with the beating did not deserve to wear the LAPD uniform. The city wasn't prepared for the outpouring of rage that followed. Residents converged on police headquarters, chanting "no justice, no peace." Over the next few days, protesters set cars, stores, and trees ablaze. LA was on fire, and it didn't take long for the demonstrations to turn violent. The major news media outlets covered the rioting extensively. The fire department received more than 1,000 emergency calls the first night alone. Protesters reportedly even attacked firefighters with axes and guns.

The overwhelming sense of lawlessness was shocking. Witnesses said that initially, police officers did not make any arrests and had even retreated from some of the hot spots. People were afraid to leave their homes. Most of the activity was concentrated in the mostly Black neighborhood of South Central. That's where protesters began throwing cans at cars passing through. Alcohol may have fueled the violence — looters destroyed more than 200 liquor stores in the area.

Who are the LA four?

On the first day of riots, four African-American men, suspected members of the notorious Crips gang, beat up a white truck driver named Reginald Denny while a news helicopter caught everything on videotape. The attack was broadcast on live television, and the men flashed gang signs for the camera. They yanked Denny out of the truck and rained blows, kicks, and punches upon him. One threw a cinder block at his head, another slammed a fire extinguisher at his face. Denny was knocked unconscious, and part of his skull was crushed into pieces. He was down for 20 minutes before four African-Americans helped him get to a hospital. Somehow, he survived.

The intersection where Denny was attacked is now infamous, as is the moniker his four attackers — the LA Four. Denny wasn't the only motorist assaulted by the mobs, but his ordeal was by far the most brutal. It stood out as an incriminating testament to how bad the riots had deteriorated in such a short amount of time. The LA Four were all convicted, with three of them sentenced to prison time.

These days, Denny keeps a low profile, seldom talks to the media, and has made peace with some of his attackers. One media outlet reported that he left California for Arizona. When he went back to the infamous intersection on the tenth anniversary of the riots, Denny said, "I will probably cry later when it all sinks in, but right now I'm just nervous."

Can we all just get along?

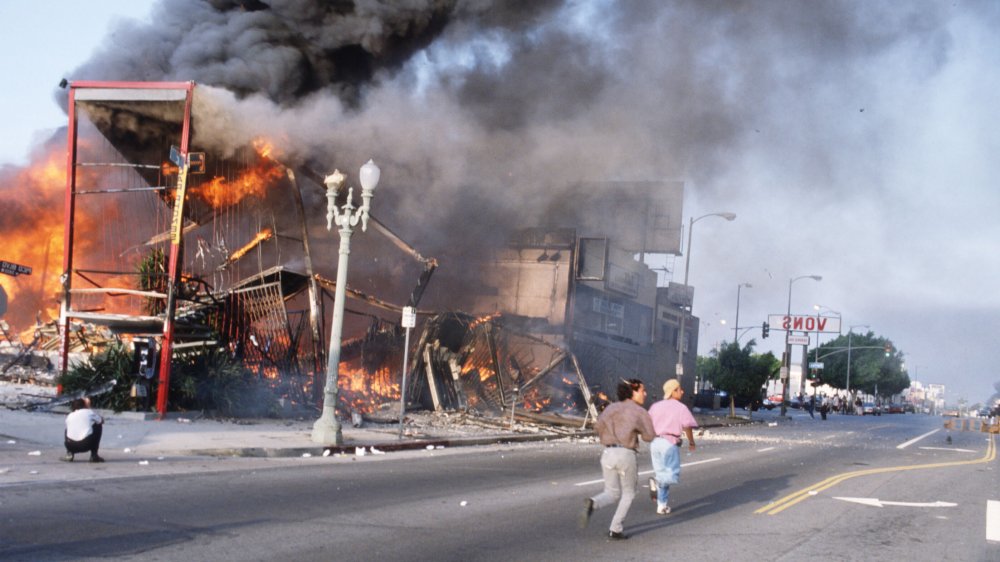

The violence was spiraling out of control as Americans watched in horror. The rioters transformed the city, and with the heavy military presence, LA looked like a war zone, according to reporters who were covering the events. Nearly 4,000 National Guard members were on the streets trying to restore order, along with 4,000 soldiers and Marines, according to The Washington Post.

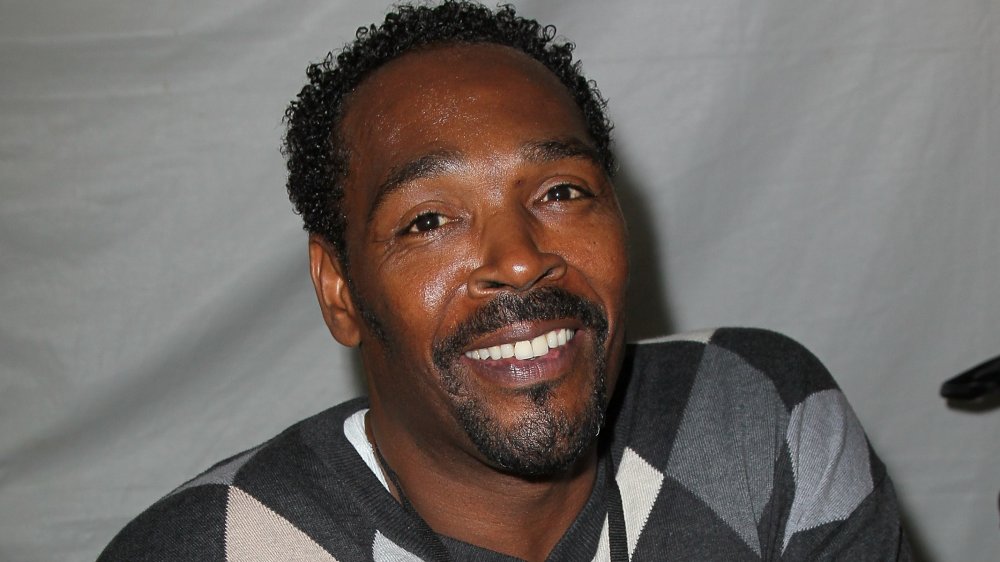

On May 1, Rodney King stood outside of a Beverly Hills courthouse with his lawyer to make an impassioned plea for the violence to stop. It was his first public appearance since the previous year. King spoke in a tearful voice, asking, "can we all get along?" It was a simple question that angered some, namely those who thought King was being too conciliatory, and touched others. But his emotional appeal did not stop the rioting, which continued until May 3.

By the end of it all, more than 50 people had died, nearly 12,000 people were arrested, more than 1,000 buildings destroyed, and the estimated cost of the damage reached $1 billion, per CNN. King's question has since been printed on trendy activist garb and commercial merchandise like coffee mugs. It's still a rallying cry for social justice and racial harmony in America. Pop culture has rephrased his words to "Can't we all just get along?"

The LAPD's paramilitary roots

For decades, African-Americans in LA had lambasted the LAPD's heavy-handedness. If the 1992 riots were the fiery explosion, then the gasoline was the officers' acquittal, and the spark was Holliday's video. Over time, the LAPD had incorporated military-style techniques that Chief William Parker (1950-1966) introduced. Under his administration, the department got its first helicopter. Parker changed the police stance away from standing on street corners to a mobile one that patrolled in vehicles.

Chief Daryl Gates, Parker's protégé, continued his predecessor's militaristic tone while he led the force from 1978 until his retirement in 1992 after the riots. He used SWAT teams and an elite unit to mingle with gang members and infiltrate immigrant communities for intelligence gathering. Members of the unit also fabricated arrests and framed innocent people. The 1991 Christopher Commission report condemned the LAPD's racist culture.

The LAPD established the SWAT unit in 1967, two years after the Watts uprising which motivated the Black Panther Party to create an LA chapter in 1968. In 1969, cops raided the organization's LA headquarters. With more than 200 cops, 5,000 rounds of ammunition, a grenade launcher, and a helicopter spraying bullets and tear gas, the predawn raid turned into a shoot-out that lasted roughly five hours. The raid was one of America's first militarized police operations.

Another cause of the LA riots

The officers' acquittal was not the only reason behind the 1992 LA riots. Local residents were still angry over a teenager's murder. Thirteen days after King's publicized beating, 15-year-old African-American Latasha Harlins was buying orange juice in a Korean-owned store. The store owner, Soon Ja Du, thought Harlins was trying to steal the $1.79 bottle when she put it inside her backpack. But witnesses said Harlins had the money in her hand. Du pulled out a 0.38 revolver and fatally shot her in the back of the head, according to FindLaw.

Du, claiming self-defense, got off with a $500 fine, 400 hours of community service, and five years of probation and was told to pay for the family's medical and funeral expenses — even though the jury found her guilty of voluntary manslaughter. The presiding judge said that she did not see Du as a danger to the community. The district attorney, however, saw the sentencing for an intentional killing as a "stunning miscarriage of justice" and tried to overturn it. Du could have gotten up to 16 years in prison.

The public outrage was strong within the community, and during the riots the following year, protesters attacked more than 2,200 Korean-owned businesses while shouting "Latasha Harlins." Her killing was not widely known, but in 2019, an LA-born filmmaker made a documentary film called A Love Song For Latasha. Rapper Tupac Shakur's 1993 hit single "Keep Ya Head Up" is dedicated to the memory of the slain teenager.

California's history of racism

Today, California is touted for its progressive politics, entering the Union as a free state under the Compromise of 1850. But the state's first elected governor, Peter Hardeman Burnett, a former slaver owner from Tennessee, wasn't exactly thrilled with the idea of allowing free Black people to enter California. He tried to pass laws prohibiting them from doing so, similar to the one he had earlier pushed in the Oregon state legislature that mandated lashing for any free Black person who did not leave Oregon within a specified time frame. Though the "lash law" took effect for a short while in Oregon, Burnett was not able to get Black exclusion laws passed in California, according to Gold Chains: The Hidden History of Slavery in California.

Government-backed housing discrimination in the state meant that African-Americans were red-lined into certain areas. They weren't able to access mortgage financing. Color-coded maps kept races within defined zones. Many lived in Fresno, California's poorest large city, and in LA, they occupied the city's southern area.

Racism in California wasn't typically as overt as it was in the American South, but the state did have a history of white-only schools, segregated beaches, and Ku Klux Klan recruitment, especially in the affluent Orange County suburbs, according to the Fullerton Observer. Other ethnic groups, alongside African-Americans, bore the brunt of racist discrimination in the state as well.

Black activism in LA

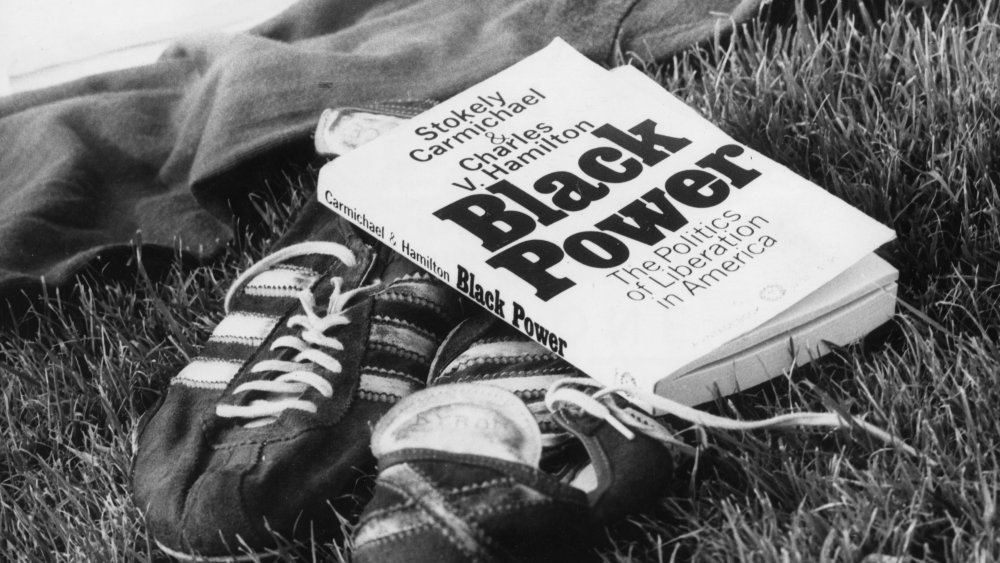

The Black Panther Party tried to break down some of the barriers that African-Americans were facing in California, starting in Oakland and quickly spreading across America. Its LA chapter was very active and was led by Bunchy Carter, dubbed the "Mayor of the Ghetto" when he headed the Slausons gang. Though Carter, a one-time follower of the Nation of Islam, is not as famous as the party's other figures like Huey Newton and Bobby Seal, he was respected in the black activist community.

Other progressive African-American-led campaigns and groups pushed for civil rights, especially within the churches and community outreach organizations. According to the nonprofit organization Black Past, the United Civil Rights Committee of LA challenged school segregation and also came up against a proposition to repeal California's Rumford Fair Housing Act of 1963, which gave African-Americans opportunities to get decent housing without discrimination. The Los Angeles chapter of the NAACP, American's oldest Black civil rights organization, started in 1914 and quickly got to work. The members, which included white professionals, gave legal defense services and lobbied for fairer policies.

Another type of street activism rose in the '80s with the rise of hip-hop culture and rap music. The music became more and more political and socially conscious, and by 1988, the southern LA hip-hop group N.W.A was shouting "F*** tha Police" on one of their hit singles. The song channeled intense hostility toward the police officers, or pigs, as the Black Panther Party had called them.

What happened to the jurors?

Hearing one of the most controversial trials in American history could not have been easy. The 12 jurors knew they had an enormous role to play in helping to administer justice in the Rodney King case. One juror later said that it might have helped the prosecution's case if King had been called to testify, but he never was. During the trial, the jurors were sometimes tense with emotions, and when it was over, some of them had a hard time moving on, according to the Chicago Tribune. People called them racist.

The trial was a momentous and life-changing experience for some of the jurors. After the acquittal announcement, many received death threats, and local police officers worked to keep them safe. Alice Debard described her life as "beyond hell." Christopher Morgan said he received hate mail, had to change his phone number, and secured his front door with iron gates. Henry King, juror number eight, told ABC News that he left town and headed for his cabin. The sole Hispanic juror said the televised images of the rioting haunted her. The presiding juror, Dorothy Bailey, published a book about the case.

Three months after the acquittal, a federal grand jury indicted the same four police officers for violating Rodney King's civil rights.

A tragic end in a swimming pool

In 1994, Rodney King was paid $3.8 million in compensation for his beating. The money was much lower than the $15 million King's lawyer was asking for, but it was still seen as a victory on several fronts. For one, King was able to testify in the second trial, and the jury panel was more diverse.

On the downside, the money created tension between King and his lawyers. Nonetheless, King tried to move ahead with his life and started a romantic relationship with Cynthia Kelly, the African-American woman who sat on the jury in his civil case. He also started a hip-hop record label. But by 2012, the LA Times reported that he was pretty much broke, getting by on odd jobs and construction work. A lot of the settlement money went to lawyers, family members, and payment for a house.

King struggled with substance abuse throughout his life and had more run-ins with law enforcement for drug-related offenses. He participated in Celebrity Rehab, a reality TV show, for two seasons. In April 2012, King published a memoir, but a few months later, Kelly, his fiancée by then, found 47-year-old old dead in his swimming pool. Investigators said they didn't see any signs of foul play, but they had to figure out how an avid swimmer drowned. Later, an autopsy report said that King was "in a state of drug and alcohol-induced delirium." A toxic mix of PCP, marijuana, alcohol, and cocaine was found in his system.

Rodney King and the LA riots changed policing forever

America's system of policing isn't perfect or anywhere near it. There's much room for improvement. Black and Hispanic people still face higher arrest rates, and the recent killings of unarmed African-Americans shines a light on institutional faults. But the Rodney King incident was a catalyst for police reform in America. Police departments around the country started trying to practice better community policing, working with communities, not against them. It also ended the "lifetime tenure" that the LAPD had in place for chiefs, pr CBS News.

Warren Christopher, the head of the independent commission that investigated the LAPD and produced the Christopher Commission report, went on to serve in President Bill Clinton's administration as secretary of state. Clinton's 1994 crime bill, however, increased federal funding for prisons. Today, critics say the bill paved the way for the mass incarceration of African-Americans.

In 2000, the federal Department of Justice began an agreement with the city of Los Angeles to allow the DOJ to supervise the LAPD for five years as it went through reforms. The LAPD is no longer a majority-white force. Crimes rates are lower, and public opinion of the police improved. Federal oversight helped clean up other police departments in the country, as well.