The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Jackie Robinson

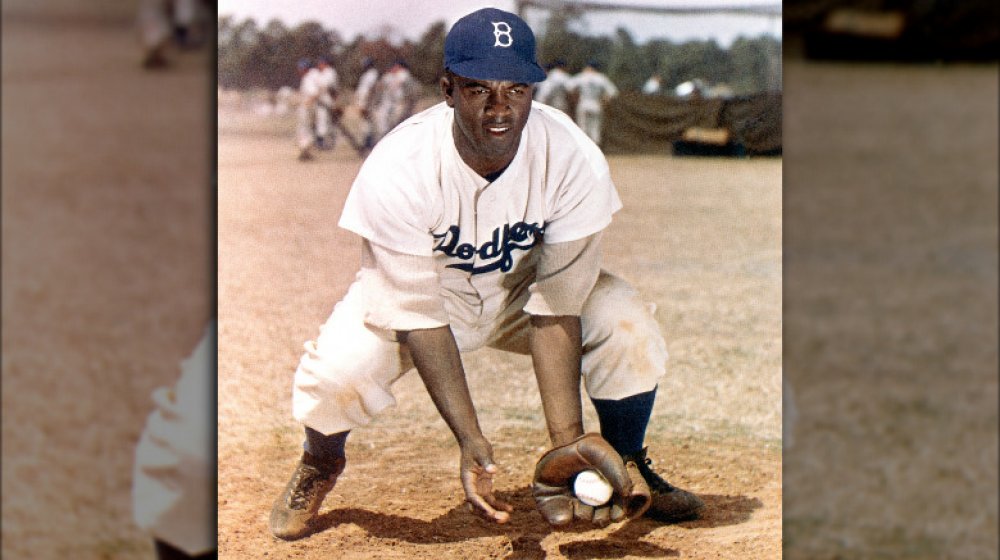

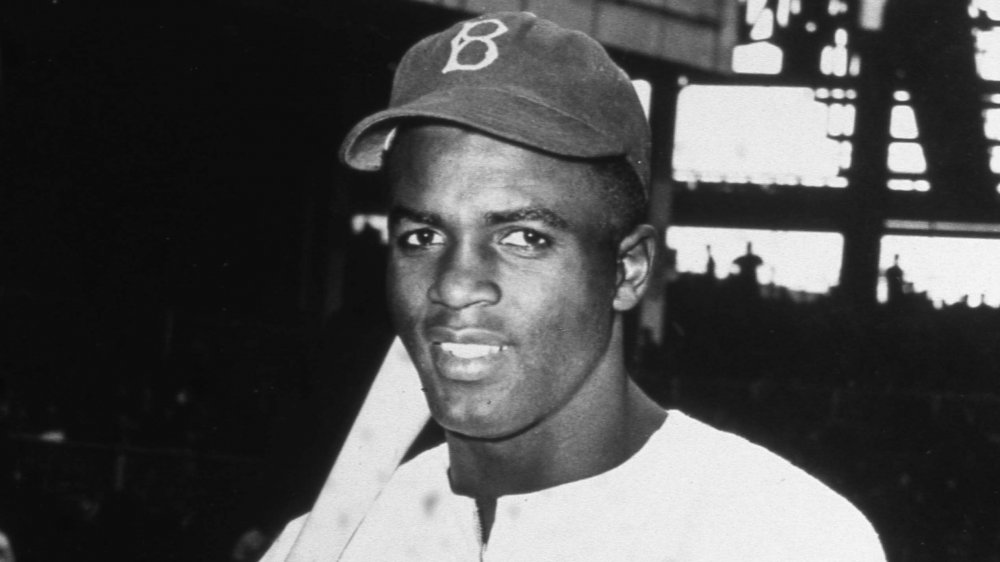

Tommy Lasorda, legendary manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, once said, "There are three types of baseball players: Those who make it happen, those who watch it happen, and those who wonder what happens." Jackie Robinson was definitely one of those who made it happen. An incredibly talented athlete, Robinson smashed baseball's color barrier and ended the era of segregation in the sport when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

To accomplish this, Robinson had to stoically endure explicit racism, violent threats, and a body that would eventually break down and betray him. What often gets forgotten when Robinson is discussed is how great a player he actually was — Robinson had a huge impact on the game, influencing its evolution from the home run-dominated pre-WWII era into a more balanced game where speed and base running skills were considered just as crucial.

Despite his fame as both a civil rights pioneer and an athlete, most people are unaware of the true scope of Jackie Robinson's struggle and impact. The tragic real-life story of Jackie Robinson doesn't take away from his heroism — in fact, it only emphasizes it.

Jackie Robinson ran with street gangs

When we think of Jackie Robinson today, we tend to think of him in terms of a relatively sanitized, feel-good version of his achievements. While focusing on his brave challenge to segregation in baseball and his on-field achievements is certainly appropriate, Robinson didn't materialize out of thin air in 1947. In fact, as SFC Today reports, Robinson grew up in poverty despite living in a relatively affluent part of Pasadena. He encountered racism on a regular basis and quickly found that he and other non-white children were excluded from activities and recreational facilities.

As the Georgia Historical Society notes, this prompted Robinson to join up with other neighborhood youths in a gang known as the Pepper Street Gang. While the gang definitely engaged in some low-level crime, stealing fruit and golf balls (which they sold back to the golfers) and committing some acts of vandalism, it was mostly harmless stuff — but it could have led to something much worse if a neighborhood friend hadn't intervened. As author Arnold Rampersad writes in his biography of Robinson, a man named Carl Anderson convinced the future Hall of Famer that his gang activities weren't worth it and helped him focus his energies on his athletics and education.

Jackie Robinson aimed for the Olympics

Jackie Robinson wasn't the only gifted athlete in his family. His older brother, Mack, is often overshadowed by Jackie, but he was an incredibly gifted athlete all on his own. In fact, as The New York Times notes, Mack overcame a congenital heart condition and a lack of funds for training to land a spot on the 1936 American Olympic team — and came in second to the legendary Jesse Owens at those games, claiming a silver medal in front of Hitler and the Nazi elite. Mack Robinson also set a number of local athletic records and spent his life serving the community of Pasadena in several capacities.

Jackie originally intended to follow in his brother's footsteps. As History reports, Jackie intended to compete at the 1940 Olympic games, and The Washington Post notes that after winning the NCAA long jump competition, there's little doubt the 1940 and 1944 Olympics would have been the natural next step for Robinson.

Of course, a little thing known as World War II broke out and canceled the Olympics in those years, meaning we'll never know if Jackie could have done better than his brother and brought home some gold medals. By the time the Olympics returned to the world in 1948, Robinson had launched his historic professional baseball career.

Jackie Robinson missed five prime playing years

Before breaking the color barrier and joining Major League Baseball, Jackie Robinson actually only played one partial season in the Negro Leagues and one full season in the International League, where he batted .349, stole 40 bases, and scored 113 runs. Once in Brooklyn playing for the Dodgers, he was a six-time All Star, a Rookie of the Year, and Most Valuable Player. He won a batting title in 1949, led the league in stolen bases twice, retired with a lifetime batting average of .311, and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, per Britannica.

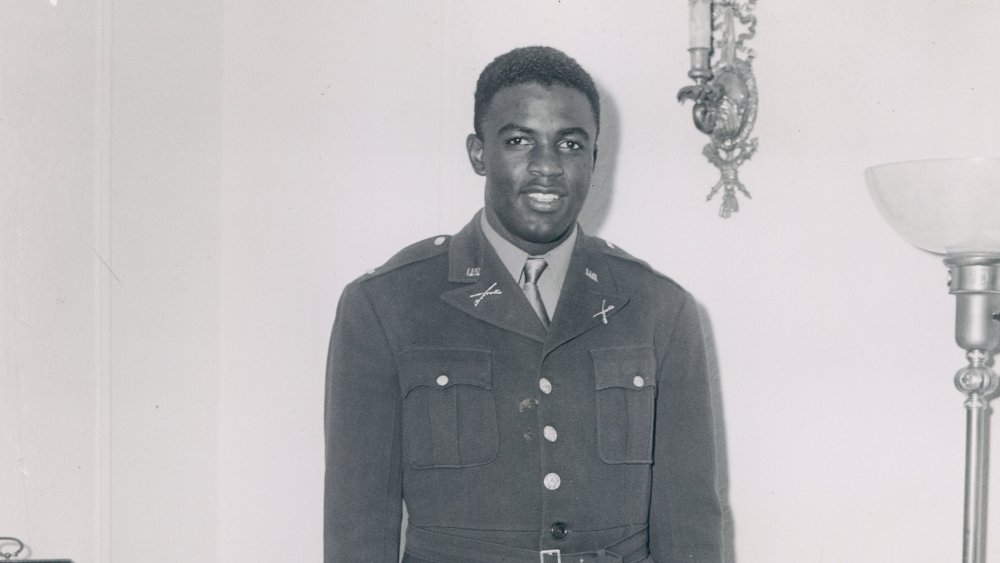

Those are some pretty impressive numbers and achievements, but it's hard not to imagine what Robinson could have done if he hadn't missed five prime playing years due to his military service.

When America was sucked into World War II in 1941, Jackie Robinson was 21 years old — in his athletic prime. He was drafted in 1942, and while he played some football (Robinson was a multi-talented athlete), as History notes, he didn't play a single inning of baseball between 1940 and 1945. There's no doubt that Robinson's statistics and impact on the game could have been much greater had the world not gone to war.

Jackie Robinson was court-martialed

Robinson didn't suddenly become interested in civil rights and racial equality when Branch Rickey suggested he join the Brooklyn Dodgers. In fact, Robinson got into a few scuffles with authorities as a young man mainly because he refused to give in to the legal segregation known as Jim Crow in the South. This got him into a lot of trouble — and almost saw him dishonorably discharged from the Army.

As PBS reports, Robinson was on a military bus in 1944 and sat down next to the wife of a fellow officer. The bus driver, taking her to be a white woman, demanded that Robinson move to the back of the bus. When Robinson refused, things got ugly, and military police eventually arrived and arrested him. He was officially charged with "behaving with disrespect" toward a superior officer and "willful disobedience of lawful command" and had to defend himself at a court-martial.

Robinson argued his case passionately and was not afraid to call out the explicit racism that had sparked the incident. In the end, he was acquitted of both charges — but the legal proceedings meant that when his unit was sent into combat, Robinson wasn't able to join them and thus never saw combat.

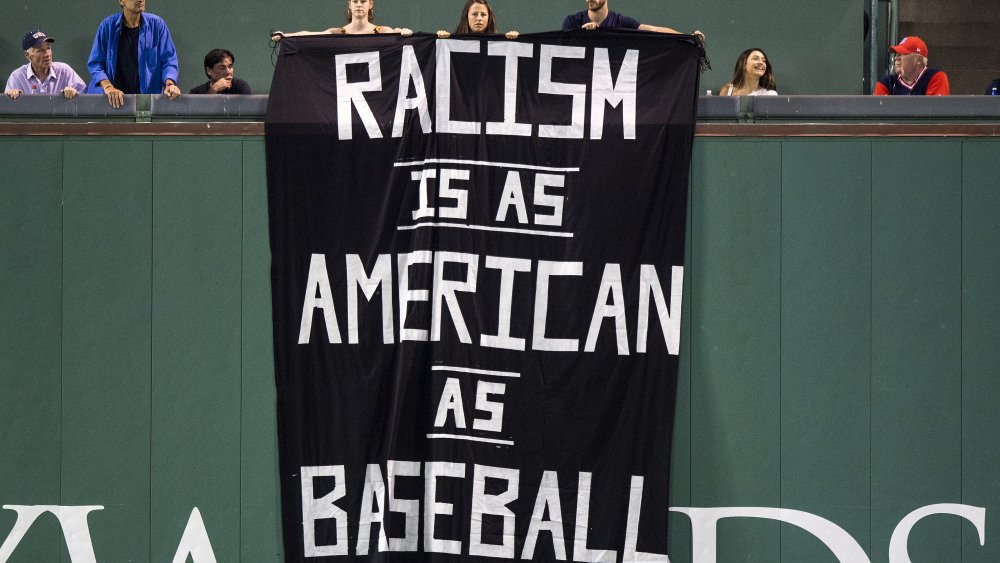

Jackie Robinson was greeted with racism in baseball

It shouldn't be a surprise that when Jackie Robinson became the first Black player in Major League Baseball in 1947, not everyone was happy to see him there. In fact, some of the worst treatment Robinson received was from his own teammates and fellow players.

As The New York Times reports, a petition circulated among the Brooklyn Dodgers players speaking out against having Robinson join the team. The player suspected of starting that petition, Dixie Walker, also wrote a letter to the team's president asking to be traded rather than play alongside a Black man. Walker later claimed he had acted not out of actual racism but due to fear of how his neighbors would react back in his hometown of Leeds, Alabama, if he played alongside a Black man.

History notes that many teams canceled exhibition games in the lead-up to the season in order to avoid playing him, and when the Dodgers played the Philadelphia Phillies, the whole opposing team – led by their manager – shouted racial slurs and insults at Robinson in an effort to drive him out of the game. And as The Atlantic notes, this racism and antagonism wasn't limited to other players. Robinson encountered bitter examples of racism in all aspects of his baseball career, from the hotels the team stayed at while playing road games to the restaurants they ate at.

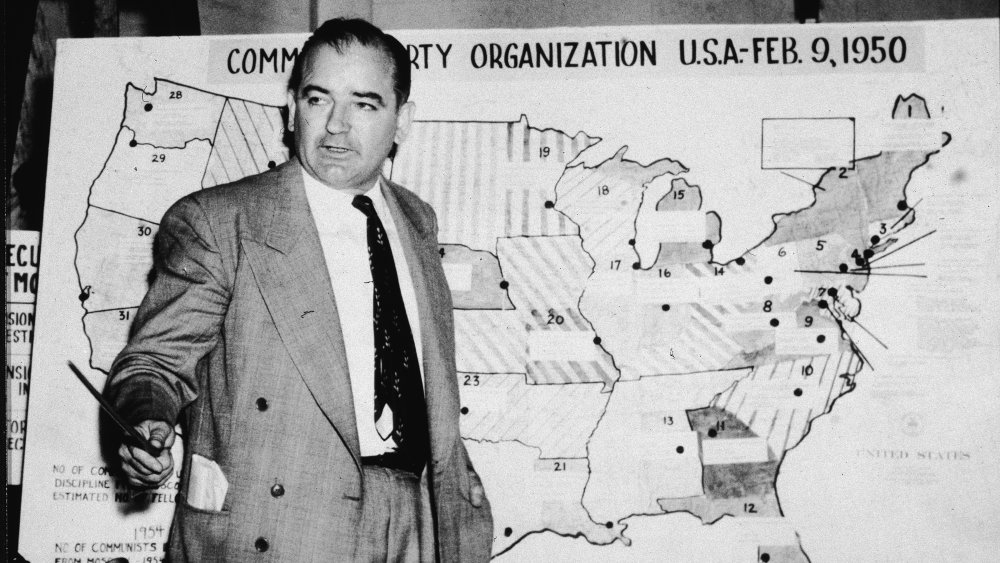

Jackie Robinson got swept up in McCarthyism

It can be difficult to believe today, but in the 1940s and 1950s, there was a real fear in the United States that communists were infiltrating our society and undermining our country. Nothing exemplified this paranoia more than the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), led by Senator Joseph McCarthy. McCarthyism, as it has come to be referred to, leveraged the power of that committee to force people to denounce others in order to save themselves and ruined many lives in the process.

As Time reports, in late 1948, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers received a call from an investigator for HUAC, who suggested that it would be good for Robinson to testify as a "friendly witness" in order to prove that he was a full-throated anti-communist. Robinson's chance came a few months later when the athlete, actor, and singer Paul Robeson was accused of having stated that Black Americans would not fight for their country because of how they had been treated historically. (Robeson did not actually say this.) Robinson was called to testify.

Robinson attempted to thread the needle. He called Robeson's supposed statement "silly" but used the opportunity to make several cogent points about racism and its negative impact on the country. Robeson was blacklisted, and his career was ruined, and Robinson later regretted his part in the hearing, saying, "I have grown wiser and closer to painful truths about America's destructiveness."

Jackie Robinson routinely received death threats

Jackie Robinson's heroism can't be understated. The color barrier that kept baseball segregated wasn't a genteel tradition — it was a racist policy backed by violence and intolerance. The decision to bring Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers wasn't just met by resistance from prejudiced players and other personnel in the game — it was met with threats of violence against Robinson and his family.

As The Washington Post notes, most of these threats came from fans and other players as Robinson took the field. He endured constant abuse and psychological pressure from fans and opposing teams, and as The Pop History Dig notes, his tireless efforts to expose the racist policies of hotels and restaurants used by the team on road trips made him a target of even more violent, threatening talk.

In fact, as author Arnold Rampersad notes in his biography of Robinson, things got so bad that the FBI was actually called in to investigate a threat against Robinson. At the beginning of the 1951 season, letters were sent to the Cincinnati Reds and local newspapers claiming that if Robinson took the field at the next Reds-Dodgers game, he would be shot by a sniper set up in a building across from the stadium. The letters were signed "The Three Travelers." Robinson chose to play anyway, and no shots rang out — but he endured similar threats for the rest of his career and, indeed, the rest of his life as his civil rights activism continued.

Segregation cost Jackie Robinson time

When Jackie Robinson stepped into a Dodgers uniform in 1947, he was officially a rookie player. In fact, that year, Robinson won the coveted Rookie of the Year Award — but he was hardly an inexperienced youngster. Robinson was 28 years old at the time and had already played several years of pro ball in the Negro Leagues.

As Sports Illustrated notes, being a 28-year old rookie is no small thing because a player's peak age in terms of statistical ability is 27, meaning Robinson was already one year past his best playing years when he debuted. The average age of a baseball rookie is 24 years old, which means that at best, Robinson lost at least four years of playing time in the Majors. According to Baseball Reference, Robinson's average yearly performance was a .311 batting average, 178 hits, 16 home runs, 86 runs batted in, 23 stolen bases, and a remarkable 111 runs scored. Four more playing years would have burnished his career totals nicely.

Segregation was only one reason Robinson started so late, of course — his military service during World War II was another. Even so, he came back to professional baseball in 1945. The effect the delay due to segregation had on his career is made clear when you consider the numbers he put up playing for the Montreal Royals in the International League: A .349 batting average with 40 stolen bases and 113 runs scored — the first two stats being career bests.

No team offered Jackie Robinson a manager job

Baseball is a sport and a business. Athletes who make baseball into a career frequently take high-level positions in a baseball organization, bringing their years of experience on the field to the back office, where their insights can guide the team's decisions. In fact, according to ESPN, only six Major League Baseball managers were not players first. And while success as a player isn't necessary to be a great manager, it seems logical that a player with Jackie Robinson's experience dealing with controversy and getting his teammates to back him up against threats and racism would make him an attractive candidate for a managerial job when he retired from the game in 1956.

But as The Atlantic reports, when Robinson retired, not a single team offered him a managerial or executive role. Instead, Robinson took a position as an executive with the Chock Full o' Nuts restaurant chain. This shouldn't be too surprising — despite Robinson's brave success in breaking baseball's color barrier, things hadn't changed that much. It took 12 years for every team in Major league baseball to finally integrate. (The Boston Red Sox were the last all-white team, adding Elijah 'Pumpsie' Green in 1959, three years after Robinson retired.) Clearly, racism hadn't been eradicated — something proved beyond a shadow of a doubt in 1962, when Robinson was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame with just 77.5 percent of the vote.

Diabetes shortened Jackie Robinson's career -- and his life

Jackie Robinson died in 1972 at the age of just 53. The official cause of death was a heart attack — his third in five years. But what really killed Robinson was diabetes.

Although Robinson's family have always maintained that he was unaware of his diabetes until after he retired from baseball, as Sports Illustrated reports, it's speculated that Robinson began experiencing the symptoms of diabetes when he was about 30 years old and that he was diagnosed in 1952, when he was 33. And The New York Times writes that Robinson experienced abnormally high blood pressure, a heart condition that worsened over the course of his lifetime, and progressive blindness that saw him lose vision completely in one eye. Curiously, Robinson didn't like to talk about his condition — he doesn't even mention the disease in his autobiography.

There's little doubt that diabetes had a terrible impact on Robinson's health. Not only was it clearly the ultimate cause of his early death, but it very likely contributed to his decision to retire from baseball in 1956 at the age of 37, just a few years after his diagnosis. His physical decline in the last decade of his life was remarkably swift and almost certainly attributable to this terrible disease.

Jackie Robinson's son died young

Aside from being a legendary athlete and hero of the civil rights movement, Jackie Robinson was a dedicated family man. He married his wife, Rachel, in 1946, and they had three children together: Jackie Jr., Sharon, and David.

Jackie Jr. joined the Army and served in Vietnam when he was just 19 years old, following his father's example of military service. According to The New York Times, he was severely injured while trying to rescue a fellow soldier. Soon after that, Jackie Jr. became addicted to drugs, an addiction that followed him home and caused his parents much distress.

But by 1972, when Jackie Jr. was still just 24 years old, his life seemed to be turning around. As noted by the New York Daily News, he'd gone into rehab at Daytop, Inc. in the late 1960s. In 1971, clean and sober, he'd been hired on as assistant regional director there. Just as his life seemed to be getting back on track, however, Jackie Jr. died tragically in a car accident. The death hit Robinson hard. He was quoted as saying "I never told him, 'I love you.' I never hugged him. I never showed him any emotion at all. I was never a father to him."

Jackie Robinson died young

Jackie Robinson achieved an amazing amount in his lifetime. He set athletic records, he served his country, he broke the color barrier in baseball, and he dedicated his life to pushing back against racism and prejudice. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, wrote a bestselling autobiography, and became a tireless agitator for racial equality in this country. It's worth considering what else he might have done had he lived longer.

In fact, it's astonishing to think that he not only achieved so much despite dying at age 53, but he did so despite spending the final decade of his life in increasingly worse health. Suffering from diabetes and a range of associated symptoms, like elevated blood pressure, blindness, and heart disease, Robinson was a gray-haired shell of the strapping athlete he'd once been.

Robinson remained clear-eyed about both his achievements and how much work was left to do. As Sporting News reports, Robinson's autobiography I Never Had it Made was published just four days after his death and contains a quote that has become chillingly prescient: "I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, in 1919 at my birth, I know that I never had it made.”