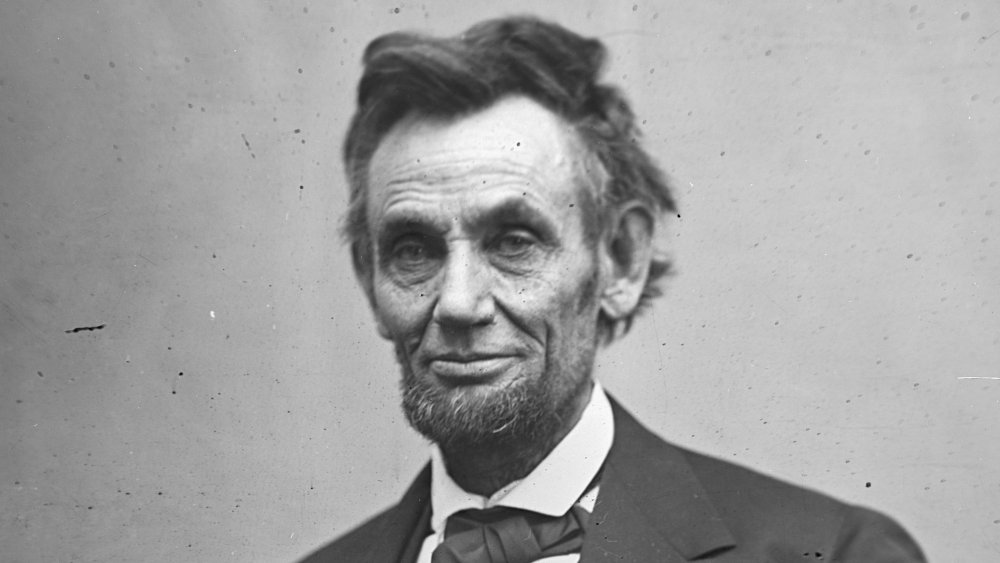

Here's What Abraham Lincoln Initially Wanted Freed Slaves To Do

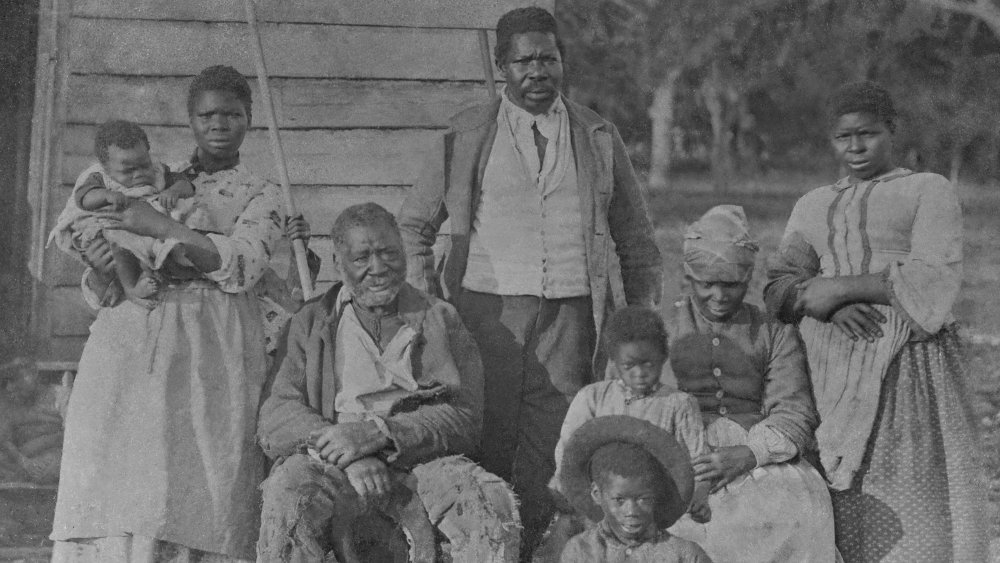

Plenty of people had plenty of opinions. A house was divided against itself, fighting a bloody war over the issue of slavery, that "peculiar institution," in the words of Southern politician John C. Calhoun. The year 1863 saw President Abraham Lincoln sign the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring an end to slavery in the states who had rebelled and joined the Confederacy, as the National Archives explains. As Union forces captured Confederate territory, the slaves they encountered would be freed. Which raised the next question: If slavery is finally abolished everywhere, what happens to all of these thousands of people, formerly enslaved, but now free?

Critics of abolitionists — those who worked for decades to abolish slavery — would occasionally dip their pens into snark-filled inkwells and suggest, in the 19th Century's equivalent of today's "Not In My Back Yard" reasoning, that it was all very well and good to free slaves, but were they really welcome among, well, white folks? (Do you want them living next door? Didn't think so.) In 1846, even Scientific American reported: "We mentioned some months since that a large number of colored people, formerly the slaves of John Randolph, had passed through Cincinnati, on their way to Mercer County, Ohio, where land, provisions, and farming utensils had been prepared for them. But we did not mention that on their arrival on their own land, the people of Mercer Co., even those who had sold them the land etc., raised a mob and drove them off...."

Lincoln learned that asking freed slaves to become colonists was a bad idea

The president also wrestled with the problem. Was it truly responsible to simply turn these people loose — people who had lived their lives with little or no self-determination, limited job skills, almost no assets? What about the families who had been fragmented by sales, separating children from parents, wives from husbands? One possibility was colonization. As posted by The National Archives, as early as 1854 Lincoln proposed that the slaves be freed and returned to Africa — specifically, Liberia, which had been founded by former slaves on the continent's West Coast. In 1861 he investigated Panama as a possible destination.

The idea didn't get far. He discussed it with a group of Black leaders in 1862, who roundly rejected the idea, as Politifact relates. Although colonization was mentioned in a preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, it was out in the final draft, according to History. Lincoln went on to propose in his last public speech that Black men who served in the Union Army — which was a huge step in and of itself — should be given the right to vote. Two years after the Proclamation, the U.S. Constitution saw its 13th amendment, abolishing slavery and involuntary servitude from the nation.

And the fight was not over.