The Untold Truth Of African-American Sports Pioneers

LeBron James, Simone Biles, Russell Wilson, Serena and Venus Williams — it's impossible to think about American sports today without African-Americans, yet there was a time in the not-so-distant past when Black athletes were kept off the court, field, rink, and track due to systemic racism and segregation. Virtually every African-American pioneer to play their respective sport was berated by fans and teammates alike, but they bravely pushed through, inspiring millions in the process.

The contributions of these courageous athletes stretch beyond sports and into the wider realm of equality in society, although many didn't get the respect they deserve until many years later. Some have only been recognized in the last few years, well after their deaths, and a couple tragically fell into poverty as their accomplishments were left out of the history books. Here are 12 of the most influential Black sports pioneers and the untold truth of their stories.

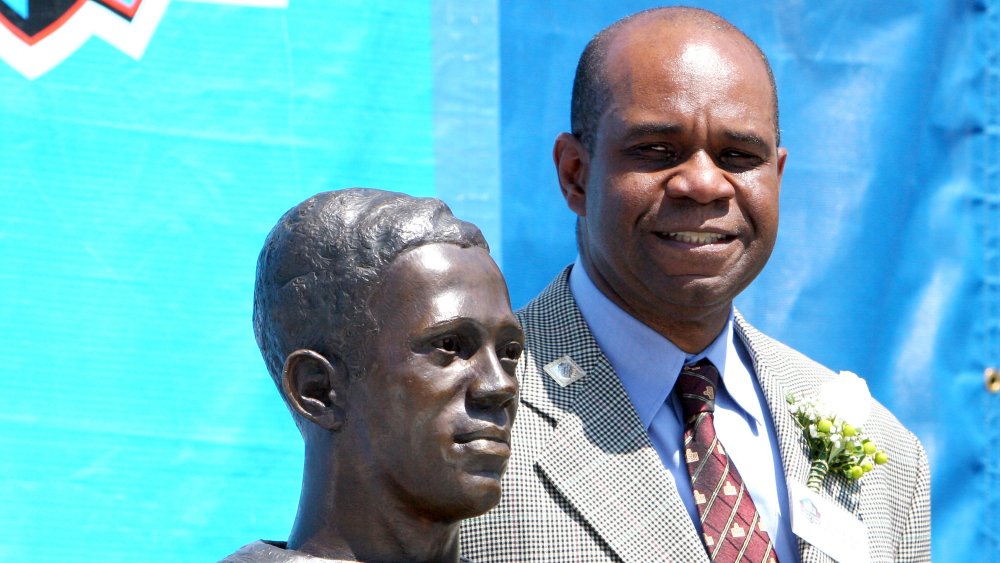

Fritz Pollard

When Frederick Douglass "Fritz" Pollard attended Brown University, he became a football star, but the spotlight didn't come without challenges. According to the New Haven Register, Pollard had to enter games using a separate entrance, and in a notable matchup with Yale in 1915, fans chided him with "Bye Bye Blackbird," among other racist taunts, but Pollard wasn't deterred. He went on to become the first African-American to play in the Rose Bowl in 1916 — a game Walt Disney himself attended. According to NFL.com, an animated Pollard flailing his hands to convince his coach to let him back in the game inspired Disney to draw Mickey Mouse with similar movements.

In 1920, Pollard went professional with the Akron Pros. With the Pros, Pollard was named a player-coach, becoming the first African-American to be named as such. "I wanted the honor of being the first black coach more than anything else," Pollard told NFL Films. In 1923, Pollard earned another accolade. According to The Undefeated, he joined the Hammond Pros as the signal-caller — also known as the quarterback — and was the first African-American to play the position in the NFL.

Pollard was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame in 2005.

Althea Gibson

As a teenager, Althea Gibson drew attention for her tennis skills and applied to competitions but was always rejected (or her applications were "lost") due to racism in the 1940s, according to The New York Times. Eventually, top players wanted to compete against the budding tennis star, and in 1950, she was the first African-American player to be admitted to the US national championships at Forest Hills. The next year, she became the first Black player to compete at Wimbledon, and six years after that, she won the competition — again, the first Black player to do so. "Shaking hands with the Queen of England," she wrote in her 1958 autobiography, "was a long way from being forced to sit in the colored section of the bus."

Gibson also won a Wimbledon doubles championship with British player Angela Buxton, who was Jewish. Like Gibson, other players didn't speak to her. "She was completely isolated," Buxton said of Gibson. "I was too, because of being Jewish. So it was a good thing we found one another."

Gibson retired from amateur tennis in 1958 and sadly fell into obscurity and poverty. In 1995, Gibson called Buxton to "say goodbye." "She said she was going to kill herself," Buxton said. "I said, 'Now, wait just a minute.'" Buxton wrote a letter to a popular tennis magazine and asked for donations for Gibson. Money came in, and the tennis pioneer lived for another eight years.

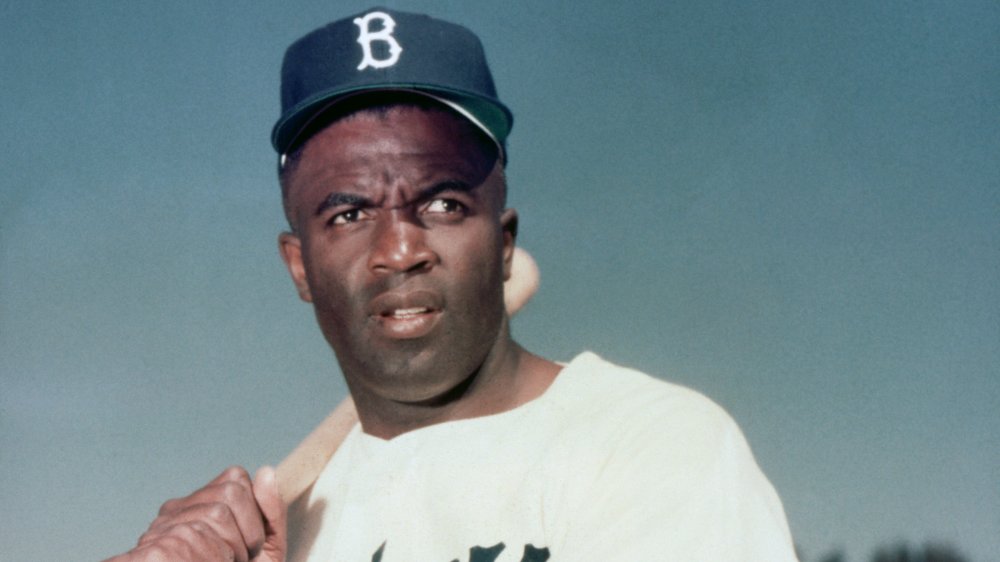

Jackie Robinson

When you think of African-American sports pioneers, you probably think of Jackie Robinson. Two years after World War II, Robinson suited up for the Brooklyn Dodgers, bucking the racist trend that saw African-Americans play in a separate league, according to History. In his first season with the Dodgers, Robinson shocked Major League Baseball when he became Rookie of the Year. In 1949, he became the first African-American MVP and went on to play in six consecutive All-Star games. In 1956, Robinson helped the Dodgers win the World Series.

After retiring from baseball in 1957, Robinson was active in the NAACP and campaigned for civil rights until he died of a heart attack in 1972. In 2013, a biopic on Robinson's life was released, and in 2019, every MLB player wore his number 42 to honor the player who busted baseball's color barrier.

A little-known fact about Robinson is that he actually wasn't the first African-American pro baseball player. According to The Washington Post, Moses Fleetwood "Fleet" Walker played catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884. There was also African-American pitcher George Stovey, who led the International League with 35 wins in 1886. In an 1887 game, the National League's Chicago White Stockings (now the Chicago Cubs) refused to play if any Black players did, and the league decided to ban any new Black players. The unwritten ban continued until 1946, when Robinson joined Brooklyn's farm team in Montreal.

Wilma Rudolph

One of 22 siblings, Wilma Rudolph was born prematurely with infant paralysis brought on by polio. According to Bleacher Report, Rudolph wore a leg brace until she was 12. Unbelievably, despite that rough start to life, Rudolph went on to become a high school and college track star.

In the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Rudolph won a bronze medal in the 4 x 100-meter relay, but her coming out party was the 1960 Olympics in Rome. There, she became the first American woman to win three gold medals in track during a single Olympics and became known as the world's fastest woman after setting an Olympic record in the 200-meter dash and a world record in the 4 x 100-meter relay. To Italians, Rudolph was La Gazella Negra (The Black Gazell), and to the French, she was La Perle Noire (The Black Pearl).

Shortly after finishing college, Rudolph retired in 1962, but despite her short career, she still managed to earn her place in the National Track and Field Hall of Fame, the US Olympic Hall of Fame, and the National Women's Hall of Fame. "Winning is great, sure, but if you are really going to do something in life, the secret is learning how to lose," Rudolph once said, according to Biography. "If you can pick up after a crushing defeat, and go on to win again, you are going to be a champion someday."

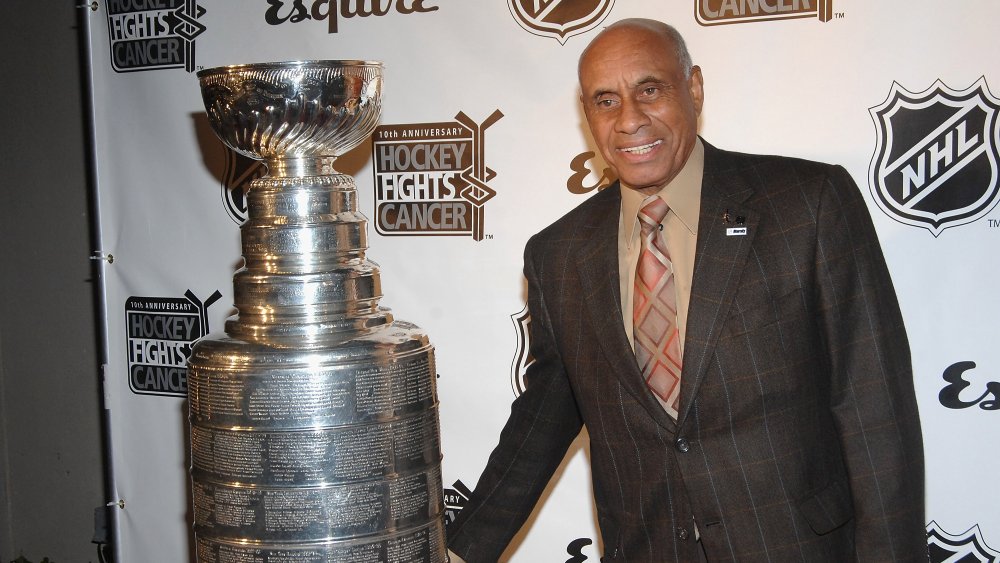

Willie O'Ree

When Willie O'Ree was 14, he went on a trip to New York and met Jackie Robinson. "When I get my chance to shake his hand, I said, 'Nice to meet you, Mr. Robinson,' I say. 'I'm Willie O'Ree,'" he recounted to The Undefeated. "Jackie Robinson says, 'Nice to meet you, Willie,' while shaking my hand. Then I said, 'I'm a baseball player, but what I really love is hockey.' He responded by saying with a smile, 'Oh? I didn't know black kids played hockey.' I smiled back and said, 'Yup!'"

Ice hockey isn't known for having too many Black players, but O'Ree became the Jackie Robinson of hockey in 1958 when he suited up for the Boston Bruins against their rivals, the Montreal Canadiens. "To me, I didn't know I was breaking the color barrier until the next morning when I read it in the paper," O'Ree said.

O'Ree only played two games in his first season but spent most of the 1960-61 season in the pros, potting four goals and 10 assists. The New Brunswick-born player said that during his time in the NHL, he received more racist taunts while playing in the US than in Canada, according to The Washington Post. O'Ree went on to have a long career in the minors and was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2018.

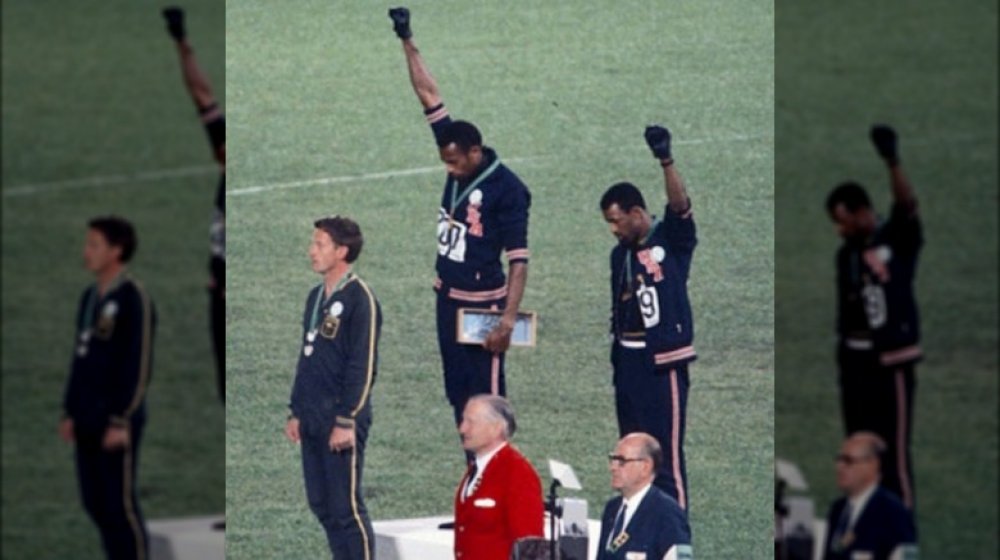

John Carlos

John Carlos (pictured above, right) told The Player's Tribune that when he was eight or nine, he had a vision that he was standing on a box in front of a crowd of people cheering, but the crowd's joy turned to fury when he raised his left hand. Around 15 years later, that vision came to be when Carlos and fellow American 200-meter sprinter Tommie Smith (pictured above, center) stood atop the podium at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City with their fists in a Black Power salute.

Carlos and Smith were subsequently kicked off the US Olympic team and faced death threats, but 50 years later, America has come around to seeing the bravery in their protest. According to USA Today, Smith and Carlos' alma mater San Jose State erected a statue of the two sprinters, and they were both inducted into the US Olympic and Paralympic Hall of Fame in 2019. "It's great when an individual [goes] from the most hated individual in society and then becomes formative icons in society," Carlos said. "Then everyone wants to be attached to that history."

The third man on the podium, Australian Peter Norman, supported the protest and also faced backlash back home for it. "If we were getting beat up, Peter was facing an entire country and suffering alone," Carlos said, according to The Toronto Star. In 2012, Australia formally apologized to Norman.

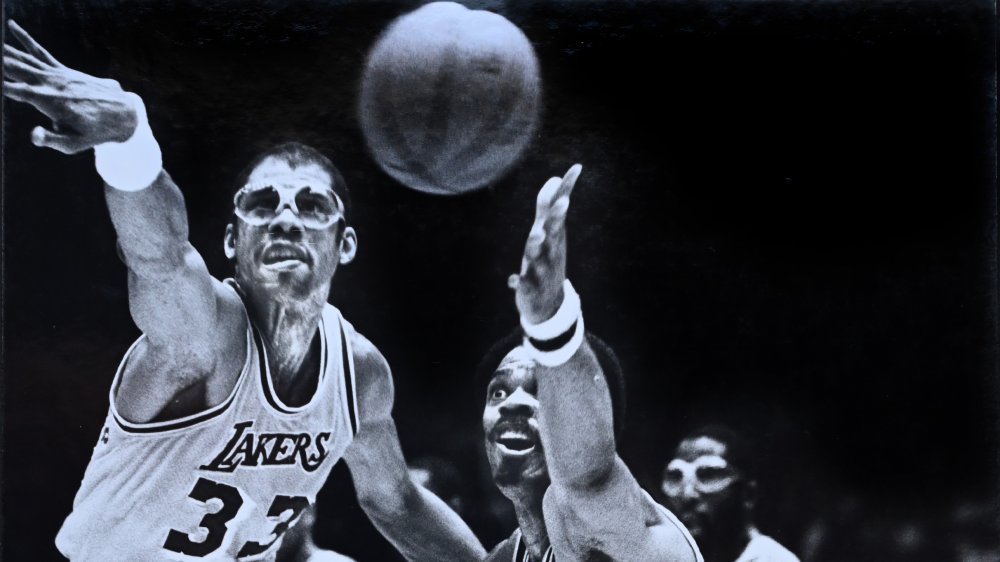

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Before Michael Jordan, LeBron James, and Kobe Bryant, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was crushing NBA records. Born Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr., the 7-foot center from New York City won three national championships for the UCLA Bruins before entering the NBA with the recently formed Milwaukee Bucks — a team he quickly made unstoppable. According to NBA.com, Alcindor easily won Rookie of the Year honors with 28.8 points per game and followed it up with a 66-win season in 1970-71 where he won MVP, the scoring title, and an NBA championship after going 12-2 in the playoffs, including a sweep in the Finals.

Despite his success in Milwaukee, Alcindor, who went on to be named Kareem Abdul-Jabbar after converting to Islam, demanded a trade to New York or Los Angeles so he could be close to other Muslims. With the Lakers, Abdul-Jabbar completed an astonishing career. By the time he retired in 1989 at the age of 42, no player had ever scored more points (38,387), blocked more shots (3,189), won more MVP awards (six), or played in more games (1,560). His longevity is attributed to his commitment to physical and mental fitness, as he'd practice yoga and martial arts to maintain his strength and meditate to keep his focus before games. "He's the most beautiful athlete in sports," said former teammate Magic Johnson.

Since his retirement, Abdul-Jabbar has been outspoken against racism, recently penning an op-ed in The Los Angeles Times about the George Floyd protests.

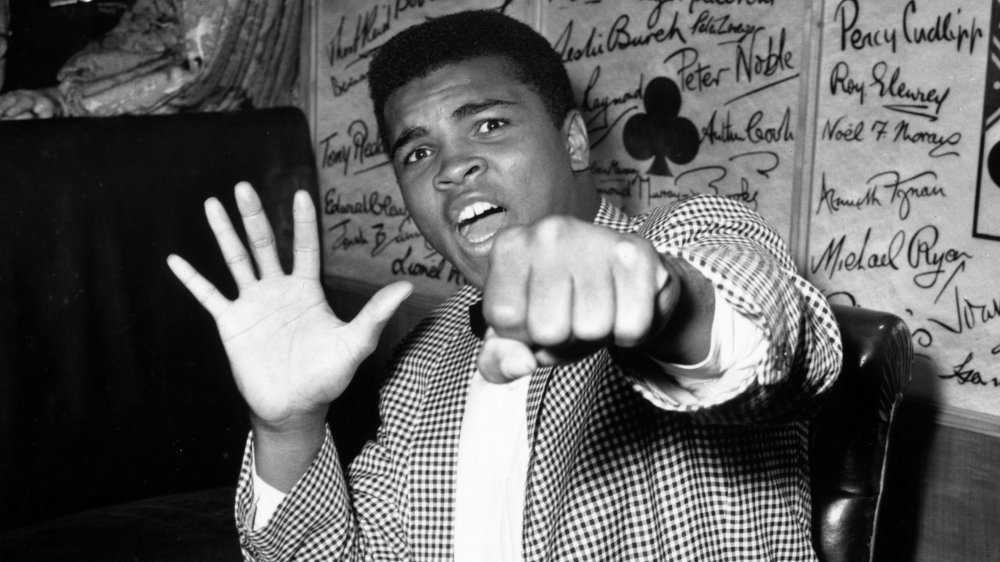

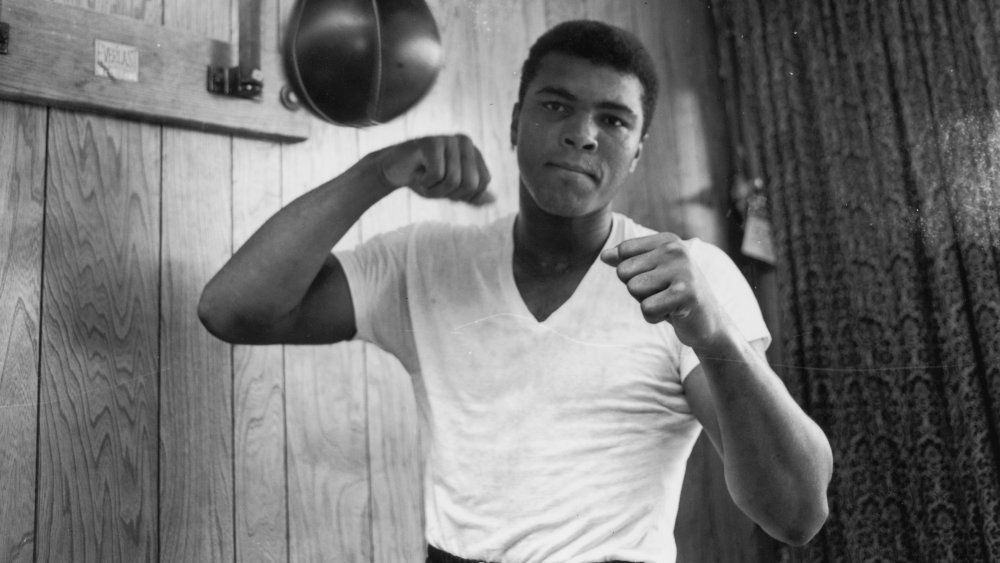

Muhammad Ali

According to Biography, when Cassius Clay was 12 years old, a kid stole his bike, and he reported the theft to police officer Joe Martin. Clay vowed to beat the thief up, and Martin, who also happened to be a boxing trainer, decided to take him under his wing. Six weeks later, the young man won his first fight.

Clay would go on to ditch his name (which he called a "slave name"), opting instead for Cassius X and then Muhammad Ali, as given by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. As a boxer, Ali was one of the greatest of all time, with a 56-5 record, including 37 knockouts, before he retired in 1981 at the age of 39.

Aside from his boxing prowess, Ali was an outspoken activist. He famously refused to join the US-led war in Vietnam, which got him arrested and left him unable to fight professionally for nearly three years in the prime of his career. Ali also questioned why popular education and religion left out Black faces. "Why are all the angels white? Why ain't there no black angels?" he said, according to Al-Jazeera. Once, Ali was so furious about racism in his hometown that he threw his Olympic gold medal into the Ohio River and lost it, according to History. The Olympics graciously gave him a replacement.

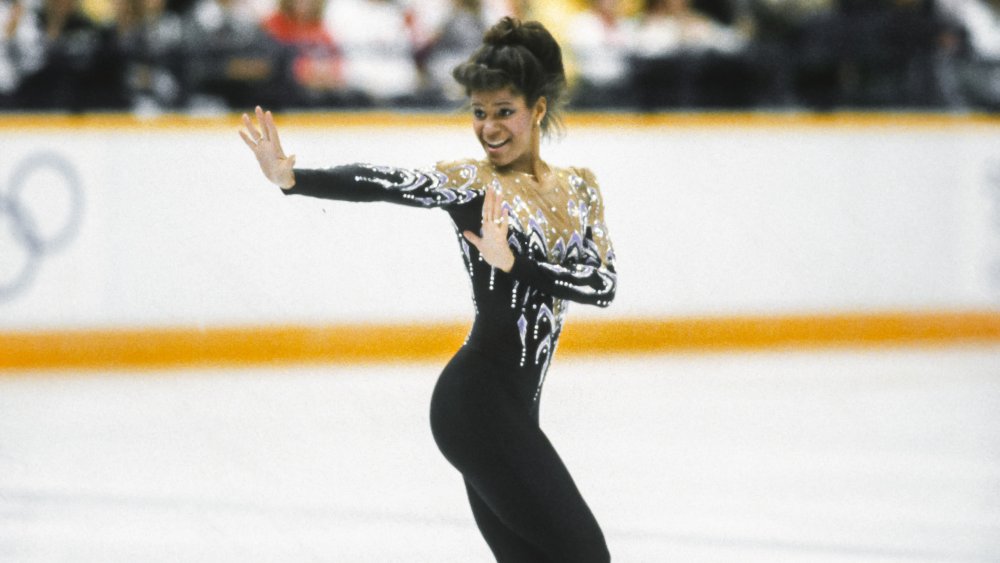

Debi Thomas

The story of Debi Thomas is easily the most tragic on this list. Early in her life, Thomas was a superb student who also won figure skating competitions. "My mother introduced me to many different things, and figure skating was one of them," Thomas told ABC Sports. "I just thought that it was magical having to glide across the ice. I begged my mom to let me start skating."

While she was rising up the ranks of figure skating in the US, the Poughkeepsie, New York, native studied engineering at Stanford. As a freshman in 1986, she won the national and world championships and was named Wide World of Sports' Athlete of the Year. At the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, Thomas took home the bronze medal, becoming the first Black athlete to do so at a Winter Olympics. At the time, she was labeled the best African-American figure skater ever, and that title holds today.

But the former star suffered from mental illness and had a terrible fall from grace, as revealed in a harrowing Washington Post feature. After retiring from skating, Thomas became an orthopedic surgeon but lost her license after she told a police officer she had a gun and wanted to hurt herself. After being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, Thomas lost her medical license, and nearly 30 years after competing in the Olympics, she was living in a trailer on social security in Richlands, Virginia.

Sheryl Swoopes

Few women have had more impact on the game of basketball than Sheryl Swoopes. In her senior year at Texas Tech, Swoopes averaged a scorching 27.4 points per game and dropped 47 in the national championship game, an NCAA record for men and women, according to The Undefeated. "People say, if you were a male, you would have gone in the [NBA draft] lottery," Swoopes told The Washington Post.

In 1997, Swoopes was the first player to sign on to the freshly formed Women's National Basketball Association, winning four titles, two Defensive Player of the Year awards, two MVPs, and a spot in the 2016 class of the Basketball Hall of Fame. There's certainly an argument to be made that Swoopes was the Michael Jordan of women's basketball. In fact, some people do say that, and once, the two Airnesses played one-on-one to see how they matched up.

"When we played, he said, 'A lot of people say you're the female Michael Jordan. Get out here and show me what you've got.' I said, 'Michael, I didn't say that. I had nothing to do with that,'" Swoopes recounted to The Baltimore Sun. "The first thing he told me [after the game] was, 'Girl, you can play.' He said, 'I watched you play and you did some things that kind of reminded me of myself.' I was going, 'Thank you' [in a timid voice]."

Tiger Woods

At the age of two, a young Eldrick Tont Woods won a putting contest with the legendary golfer Bob Hope on the Mike Douglas Show. At eight, he showed off his skills on Good Morning America, and at 21, the golf ace known as Tiger Woods won the US Masters at Augusta, becoming the first African-American do so, per Biography.

To Woods' father Earl, who is of African-American, Chinese, and Native-American descent, winning at golf was satisfying revenge against a sport with longstanding racist traditions, according to Sports Illustrated. To Woods himself, who identifies as "Cablinasian" due to his mother's Thai, Chinese, and Dutch heritage, being a Black man at the top of his sport forces America to have an important, uncomfortable conversation about race. "Golf has shied away from this for too long. Some clubs have brought in tokens, but nothing has really changed. I hope what I'm doing can change that."

In his first decade, Woods had a shot at breaking Jack Nicklaus' record of 18 major titles, but personal issues and injuries derailed those thoughts. In 2009, a media frenzy over reports that Woods was cheating on his wife knocked him off his game, leading to an almost 11-year slump without a major title. Finally, in 2019, Woods roared back with his 15th Masters win and was recognized for his "relentless will to win, win, win" by Donald Trump with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Gabby Douglas

Gymnastics was not known to have many African-Americans ... until Gabby Douglas came along. At the age of four, Douglas could already do one-handed cartwheels, and at eight, she won her first state championships, according to Biography. By 16, Douglas was competing for the US at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London with the team that won gold. She also won the individual all-around category, becoming the first African-American to do so.

But despite being one of the most recent pioneers on this list, Douglas proved that America still has a long way to come before it achieves equality in sports. During the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Douglas again helped her team to gold but was relentlessly bullied. "She's had to deal with people criticizing her hair, or people accusing her of bleaching her skin. They said she had breast enhancements, they said she wasn't smiling enough, she's unpatriotic," her mother told Reuters. "You name it, and she got trampled. What did she ever do to anyone?"

Douglas' impact on gymnastics has already been felt, as she was the one to inspire Simone Biles, the most decorated US gymnast ever, to join the sport. "Growing up, you don't see a lot of African American gymnasts," Biles said according to Business Insider. "I remember when Gabby Douglas won I was like, 'Oh my gosh, if she can do it, then I can do it.'"