The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Madam C.J. Walker

Madam C.J. Walker's story is a fascinating one — a true tale of struggle and triumph. Starting out life in debilitating poverty — as an orphan, a child laborer, a too-young wife, a widow, and a single mother — Walker was able to use her natural ingenuity and business savvy to build an incredibly successful beauty empire.

At a time where Black women were not regularly catered to in terms of beauty products, Walker was able to establish credibility and a massive following as a Black woman creating products designed specifically for Black hair. Her inventiveness and know-how led her to become the first self-made woman millionaire — not just the first African American woman. And it wasn't merely her inventiveness or great wealth that earned Walker admiration and respect, but also her generous, philanthropic spirit. Walker used her vast fortune to give others in Black communities a better start in life and help those who were struggling more chances to succeed.

Walker has been receiving even more attention thanks to the recent Netflix series, Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker. However, given her prominence in American history, it's important to understand and separate the fiction depicted on screen from the facts of Walker's real life. This is the crazy real-life story of Madam C.J. Walker.

Madam C.J. Walker was orphaned at a young age

Before she became the illustrious Madam C.J. Walker, the future entrepreneur was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867, on a cotton plantation near Delta, Louisiana, according to Encyclopedia Britannica. She was the fifth child of Louisiana sharecroppers Owen and Minerva Breedlove. Her parents had been recently freed slaves and Sarah was the first of their children to be born after the Emancipation Proclamation. Both of Sarah's parents were dead from unknown causes by 1875 leaving the then 7-year-old to be raised by her older, married sister, Louvinia.

Later on, according to Biography, Sarah, her sister, and brother-in-law moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi for better employment opportunities. Even little Sarah had to work to help support the three of them. Although no documentation exists, she was probably employed to pick cotton and perform household chores. However, all seemed not to be well within Sarah's family unit as her sister's husband was said to be unkind and abusive towards young Sarah. At the time, Sarah's only way out was through marriage.

Madam C.J. Walker was married three times

Since she only had one avenue to escape her abusive brother-in-law and grueling work environment, Sarah ended up marrying at the shockingly early age of 14-years-old. She married Moses McWilliams with whom she had her only child, A'Lelia (originally born "Lelia"). By 1887, Sarah was a widow and a single mother at the age of 20. According to Vanity Fair, it's assumed that McWilliams died, but there is no definitive report as to whether he actually passed away or simply walked out. With a little girl to support, Sarah moved to St. Louis near her older brothers and took a job as a washerwoman. The job paid her a mere $1.50 per day, but it was enough to send her daughter to the local public school. Sarah herself attended night school whenever she had the chance.

Later, Sarah married a laundry worker named John Davis in 1894, most likely to help out economically. However, the two divorced in 1903, and according to a Vanity Fair interview with Madam C.J. Walker's descendant, A'Lelia Bundles, it would appear that Davis was an alcoholic and a serial cheater. Her final and most notable marriage was to adman and salesman Charles Joseph Walker. Despite being married to C.J. Walker for only four years (they divorced due to drinking and cheating on his part), Sarah Breedlove took from him the name for which history remembers her.

Madam C.J. Walker experienced early hair loss

Madam C.J. Walker faced another significant problem in her life. She was losing her hair. According to Henry Louis Gates Jr. on The Root (via PBS), regular bathing proved more difficult in the early 1900s given that most Americans lacked indoor plumbing. With hair washing being so infrequent, hair was left highly exposed to bacteria, pollution, and lice. And as a laundress, Walker was regularly exposed to lye soap, steam, and dirt.

But Walker was far from being alone in her suffering. Due to the lack of resources, premature hair loss was not an uncommon condition, especially among Black women. And it was doubly frustrating for Black women because most hair products at that time catered to white women's hair. The most popular and widely available hair products of the day were not suited to adequately treat Black hair.

As noted on Biography, Walker did not want to resort to covering her bald patches with a head wrap and decided to seek out a cure for her condition. Her brothers were barbers, so she was able to garner some basic hair care knowledge from them. Additionally, Madam C.J. Walker used her own knowledge of soap properties from her job as a washerwoman, in order to experiment with at-home scalp remedies of her own. She also found significant success after discovering another Black woman's hair product.

Madam C.J. Walker wasn't the only one in the Black hair care business

Madam C.J. Walker got her start in another Black woman's hair care company — the Poro hair company run by Annie Turnbo Malone. Malone had a signature formula created for Black women — "The Great Wonderful Hair Grower." Walker herself found some success in using it to treat her scalp condition — she even became a Poro sales agent. However, that didn't stop Walker from continuing to experiment with her own homemade products.

The Netflix series, Self Made, portrays Malone's character as a bi-racial, light-skinned woman out to sabotage the darker-skinned Walker. As reported by Elle, the real Annie Malone was not bi-racial and colorism was never a factor in her rivalry with Walker. Nor did she ever hatch any great scheme to ruin Walker. There's certainly evidence that there was a falling out between the two — Walker did use Malone's business and products as a blueprint for her own, after all, although they weren't completely identical.

Both Malone and Walker had very similar businesses, products, methods. They were both wildly successful businesswomen and generous philanthropists. So, why is Madam C.J. Walker more well-known? Possibly, according to Town and Country, because Malone's records weren't as well-maintained and potentially due to A'Lelia Walker's gargantuan efforts at preserving her mother's legacy. Additionally, Malone's business suffered brutal hits between a costly divorce and the Great Depression, though she managed to hold on for several decades. But Walker's reputation ultimately surpassed her former employer's.

Madam C.J. Walker created her own hair line

After experimenting with her own hair potions at home, Madam C.J. Walker worked a commission-based job with Annie Turnbo Malone's hair product company and she also took a job as a cook for pharmacist Edmund L. Scholtz. According to Biography, Schlotz helped teach Walker the chemistry behind hair care which helped her to refine her own homemade products.

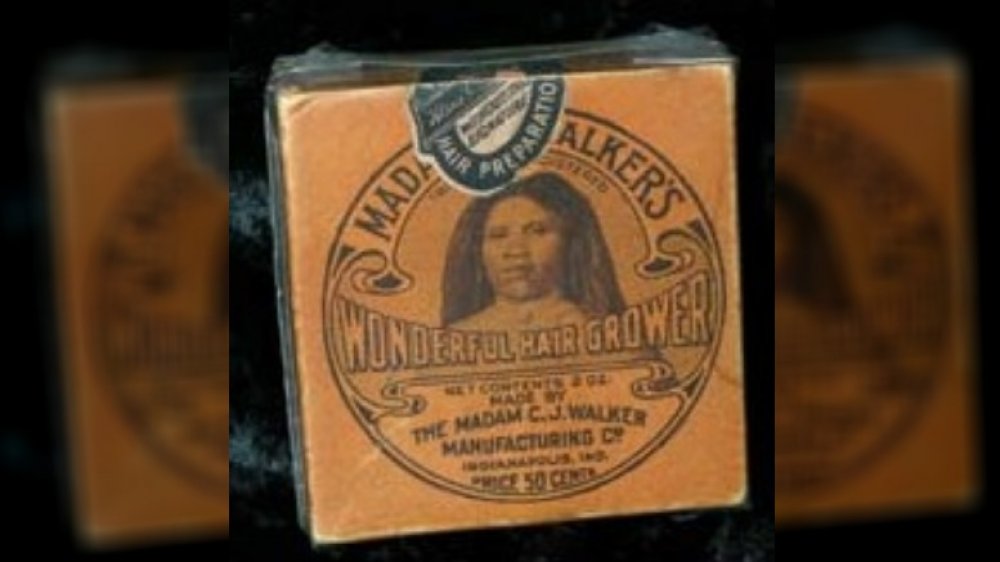

By 1906, Walker had created her own hair growth formula called "Madam Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower," made from ingredients such as precipitated sulfur, copper sulfate, beeswax, petroleum jelly, coconut oil, and a violet extract. While this sounded suspiciously similar to the product of her former employer — Annie Malone — it would appear that Walker used the formula for the initial layout but tweaked it enough to make it her own. According to a report in Collectors Weekly, Madam C.J. Walker's descendant, journalist A'Lelia Bundles, reported that several women of that time hawked secret hair formulas, so it was unlikely that they were derived from the same source.

Madam C.J. Walker built a thriving business

Madam C.J. Walker started out by selling her products door-to-door and at church and club events and later utilized ad space in black newspapers. It also helped that Walker's third husband — a professional adman and salesman — did her advertising and marketing for her in the early stages of the business. Charles Joseph Walker – a shrewd advertiser — was the one who suggested that she use his name for her business which led her to adapt the moniker of "Madam C.J. Walker." The name was intended to give her business distinction with "Madam" lending a hint of French refinement. It worked. And Walker made sure the name stuck around even when C.J. didn't.

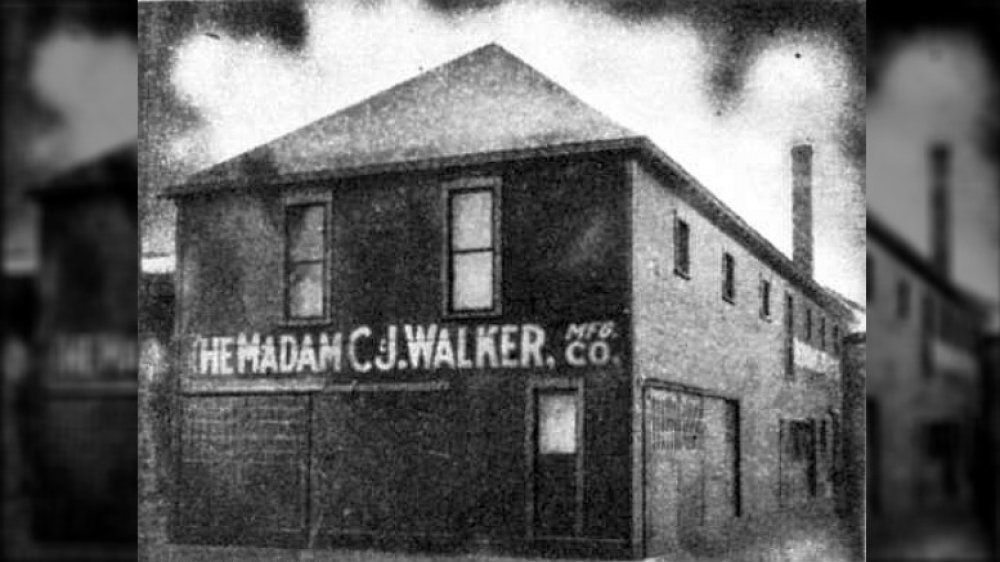

Besides her hair grower, Walker also created vegetable shampoos, a pressing oil, cold creams, and even an improved hair straightening comb. She also preached her "Walker Method" of hair care which recommended regular washings, the use of sulfur-based products, and regularly massaging the scalp. According to A'Lelia Bundles, none of these methods were new, but Walker (and Annie Malone as well) helped popularize them. As detailed by Henry Louis Gates Jr., Walker's satisfied customers were so impressed that many became her sales agents and helped her expand to new markets. And Madam C.J. Walker could afford to pay her agents generous commissions. As the business continued to expand, The Walker Manufacturing Company and a beauty school opened in Pittsburgh in 1908 (operations would eventually transfer to Indianapolis in 1910).

Madam C.J. Walker was the first self-made millionairess

Madam C.J. Walker was not simply the first Black woman millionaire — she was the first self-made woman millionaire ever, according to Guinness World Records. At the time of her death in 1919, Walker's total assets equaled over $1 million which would be approximately well over $15 million by 2020 standards. There are some who argue that Walker's former employer Annie Turnbo Malone may have hit the $1 million mark before her, but Malone's financial records were never as well documented as Walker's.

It is also of significant note that Madam C.J. Walker was a self-made millionaire — as in, she never inherited or married into her wealth. While she had the good fortune to have substantial support from her husband, daughter, and barber brothers in her business, it's generally agreed that Walker's aptitude, business savvy, and innovativeness propelled her to the top. She began her life with very little and had to undertake exhausting labor in order to survive and support herself and her daughter. Her natural ingenuity and industriousness truly allowed her to become as successful as she became.

Madam C.J. Walker lived next door to John D. Rockefeller

Madam C.J. Walker eventually became so wealthy that she could afford to have an illustrious mansion built in Irving, New York — and have millionaire John D. Rockefeller himself as her next-door neighbor. Although Self Made showed Rockefeller and Walker having a conversation in their neighborhood, there is no evidence that the two ever actually spoke or met each other as noted in by Elle.

According to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Madam C.J. Walker commissioned her New York home to be built in 1916 by architect Vertner Woodson Tandy — New York state's first licensed Black architect. Her home was a splendid 30-room Italianate mansion in the Hudson River Valley — and positioned so strategically that it could be seen by anyone traveling between New York City and Albany. Walker named her mansion Villa Lewaro after her daughter, whose full name at the time was Lelia Walker Robinson. Villa Lewaro was later named a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

Madam C.J. Walker collaborated with Booker T. Washington

Educator, author, and orator Booker T. Washington was the most powerful and influential Black man of the time, and Madam C.J. Walker hoped greatly to gain an endorsement from him. She attempted to make contact with him at the 1912 National Negro Business League as she wanted a chance to speak during the conference. However, according to A'Lelia Bundles, Washington ignored her, feeling that her beauty products were encouraging Black women to look more like white women. But Walker was not easily put off and didn't let Washington's rebuff discourage her. Instead, during the convention, she decided to address him right from the audience.

Although initially annoyed by her boldness, Washington and Walker did eventually form an alliance (there is no evidence that there was ever any real dispute between the two as was shown in Self Made). As noted by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Washington grudging recognized that many Black women — even his own wife — admired the smoother, straighter hairstyles that Walker's products helped create. Plus, he and Walker shared fixation on cleanliness and good hygiene, and both were supporters of educational opportunities for Black people. Recognizing and allying himself with Madam C.J. Walker was prudent. According to Elle, Washington visited Walker's home when he attended the opening of the Indianapolis YMCA, and Walker made a generous donation to his organization, The Tuskegee Institute. At the next National Negro Business League convention, Washington invited Walker to be a keynote speaker.

Madam C.J. Walker was a great philanthropist

Having built an incredible fortune, Madam C.J. Walker made a point to use her wealth to help others in Black communities. She knew firsthand what it was like to struggle and wanted to give other Black Americans chances to succeed. An advocate for education, as noted in O Magazine, Walker gave generously to Black colleges and secondary schools to help others have the chance at the education she was forbidden due to Jim Crow laws in Louisiana and Mississippi. She donated to educational institutes such as the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina, the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute in Florida (known today as Bethune-Cookman University), and Booker T. Washington's Tuskegee Institute.

According to The Smithsonian Institute, Madam C.J. Walker also gave to social service organizations that focused on the well-being of Black Americans such as St. Louis Colored Orphans' Home, the YMCA, St. Paul's AME Mite Missionary Society in St. Louis, the Flanner Settlement House in Indianapolis, and the Alpha Home elder-care facility in Indianapolis. She also gave significantly to the NAACP to aid their efforts in stopping lynching in America.

Madam C. J. Walker disapproved of her daughter's choice in husbands

Like her mother before her, A'Lelia Walker also married three times. Her first husband, John Robinson was a hotel waiter whom she divorced in 1914. While the Netflix series, Self Made heavily hints that A'Lelia was gay, there are no records that support this conclusion. According to an in-depth O Magazine overview which included an interview with A'Lelia Walker's granddaughter, A'Lelia Bundles, the real-life tension between mother and daughter came as a result of A'Lelia's last two husbands — Dr. Wiley Wilson and Dr. James Arthur Kennedy. Both men were well-known, handsome doctors — and they were both interested in A'Lelia. However, Wiley Wilson had a distinct "bad boy" vibe that Madam C.J. Walker didn't trust. She infinitely preferred Kennedy, who was the more stable option.

Wiley became A'Lelia's second husband, and when marriage didn't result in Wiley amending his bad boy ways, A'Lelia left him for Kennedy. A'Lelia informed Walker of her decision to marry Kennedy while her mother was on her deathbed — evidently, Walker received this news with much delight and relief.

Madam C.J. Walker left a legacy

Madam C.J. Walker died in 1919 of hypertension and kidney failure in her New York home, Villa Lewaro. She was 51-years-old. At the time of her death, Walker had just purchased a property in Indianapolis with plans of new headquarters. In 1927, the building was completed and instead became the Madam Walker Theatre Center, which became another National Landmark. According to Biography, the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company ended its operations in 1981, but there is a line of cosmetics and hair care products bearing the name "Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture" available at Sephora today.

Walker's daughter A'Lelia lived on to become a renowned patron of the arts, a delightfully eccentric hostess, and an influential figure of the Harlem Renaissance. She became good friends with writer Langston Hughes and poet Countee Cullen and even hosted her own literary society in her New York apartment. A'Lelia Walker died of hypertension in 1931. Today, Madam C.J Walker's memory lives on through her great-great-granddaughter — writer, journalist, and news producer, A'Lelia Bundles. Bundles wrote Walker's biography which inspired the current Netflix series and will be coming out with a new biography in 2021 about her grandmother and namesake, A'Lelia Walker.