The Untold Truth Of Thurgood Marshall

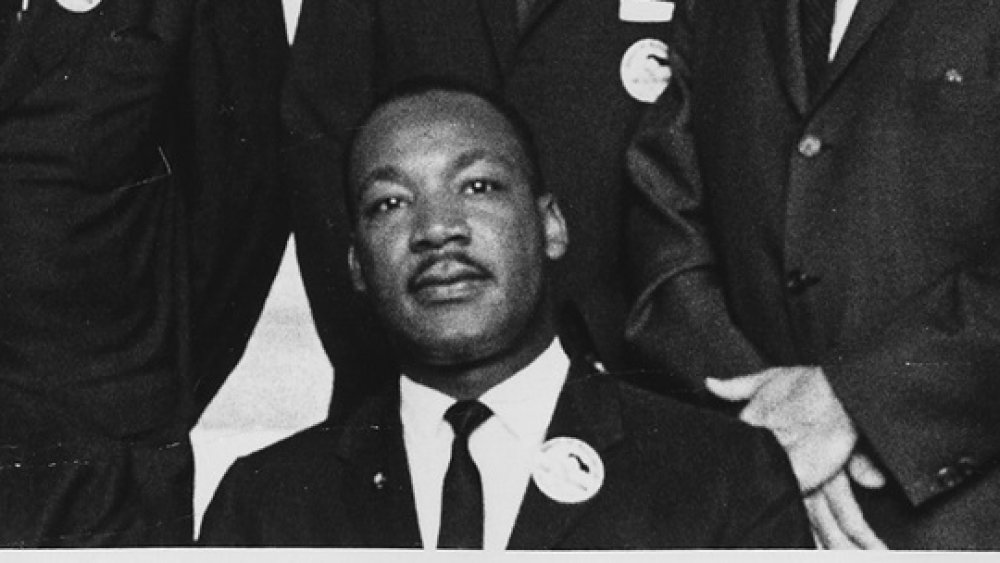

Before the battle for civil rights took to the streets in the mass demonstrations of the 1960s, lawyers around the country were risking their lives to secure those rights and fight injustice in the nation's courtrooms. One man became the face of the legal struggle, drawing crowds hostile and affectionate everywhere he went.

In the 1930s, Thurgood Marshall was a hero among Black communities in the South. At a time when lynching, segregation, and racist laws were used to keep Black people separate, terrified, impoverished, and very much unequal, watching a Black lawyer not only confront all-white juries, prosecutors, and judges but actually win was inspiring.

As chief legal counsel of the NAACP, Marshall oversaw hundreds of cases. He set a record for the number of cases argued and won in front of the Supreme Court — most famously, Brown v. Board of Education. And his quick wit and charm won over allies and enemies alike. But he was not without his flaws and complexities. This is the untold truth of Thurgood Marshall.

Thurgood Marshall's parents taught him to fight for justice

Thurgood Marshall credited his family for instilling in him his determination to fight injustice through the law. His maternal great-grandfather was kidnapped from Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) when he was a child, and enslaved in Maryland. But he was so resistant that the man who kidnapped him eventually set him free.

According to Thurgood Marshall: A Biography, Thurgood 's mother, Norma, was one of the first Black people to graduate from Columbia Teachers College. Thurgood's father, William, quit high school and eventually worked as a railroad porter and head steward at a whites-only country club. Despite his lack of formal education, William was determined that Thurgood and his older brother Aubrey be informed about the world. He made them read the newspaper every day, and held debates with them around the dinner table, in which they were expected to defend every point they made. William would also take his sons to watch court trials in Baltimore. Thurgood Marshall told U.S. News and World Report, "He never told me to become a lawyer, but he turned me into one."

Even though William "looked" white, he never lied about his race in order to have an easier life. He and Norma instilled in their sons the understanding that not only were they as good as any white person, but being Black was something to be proud of.

Thurgood Marshall was never a pushover

Thurgood Marshall's school days didn't exactly indicate Future Supreme Court Justice. He was far more interested in girls and causing trouble than he was in studying, and at home, he hung out with the tough kids. He was disruptive in class, teasing other children — although he also changed his name from "Thoroughgood" when he was six to escape taunts. One of the punishments he faced came in useful later: he was made to memorize the Constitution. He knew the whole thing by age 16. Marshall still managed to graduate a year early, and also led the debate team and took part in the student council.

As Marshall grew up, he wasn't afraid to literally fight back against the racism he encountered in segregated Baltimore. According to Thurgood Marshall: A Biography, his father William had told him to fight anyone who used racial slurs against him. He was once arrested over a physical altercation with a white man who pulled Marshall off a trolley car because he got in ahead of a white woman. At the time, Marshall was still in school but also had a job as a delivery boy. His employer, Mortimer Schoen, put up bail and called his own lawyer to secure Marshall's release.

A college that excluded Marshall for being Black named a library after him

After high school, Thurgood Marshall followed his older brother Aubrey to Philadelphia's Lincoln University, the oldest Black college in the US. He enrolled for pre-med because his mother wanted him to become a dentist but remained just as fun-loving: he joined a fraternity and led the debate club.

Before his second year started, ThoughtCo. says Marshall switched from medicine to law. After graduating, he applied to the University of Maryland School of Law, but was turned down because he was Black. Instead, Marshall earned his law degree from Howard University Law School in Washington, D.C. He worked three jobs and his mother pawned her wedding and engagement rings to pay his out-of-state tuition.

Marshall graduated top of his class and passed the bar exam in 1933. In 1936, Marshall and his mentor Charles Hamilton Houston served as the attorneys for Donald Gaines Murray, a law student who filed suit after he, like Marshall, was rejected by the University of Maryland School of Law over his race. Marshall, Houston, and Murray won the case, forcing the University of Maryland to desegregate. In 1980, the University of Maryland named its new law library after Thurgood Marshall, but the then-Supreme Court Justice refused to attend the naming ceremony, saying the college was only trying to "salve its conscience."

Marshall became the architect of the NAACP's fight against segregation

At Howard University Law School, Thurgood Marshall grew close to the dean, Charles Hamilton Houston, a civil rights legend in his own right. Houston planned to recruit up-and-coming Black lawyers to fight the NAACP's battle against segregation laws. He masterminded the strategy of attacking the "separate but equal" doctrine that had formed the legal backbone of segregation since 1896 by challenging segregation in schools.

Marshall joined the NAACP while still in law school. After passing the bar, he set up his own private practice in Baltimore, but in 1935 he started working as a part-time legal counsel for the NAACP. According to Baltimore Magazine, in 1938, Marshall became the NAACP's chief legal counsel — replacing Houston — and the architect of Houston's plan. He founded the Legal Defense Fund in 1940, which served as the engine in the legal battles of the Civil Rights Movement.

Thurgood Marshall traveled all over the country, defending plaintiffs in cases that could strike a blow to segregation and racism. Many involved schools, but he also tackled racism in other areas, including housing, primary elections, and military justice. In 1940, he won his first of many victories in the Supreme Court: over the next 21 years, he won 29 of the 32 cases he argued before the Court — a record. At one point, he was overseeing as many as 450 cases at the same time.

Thurgood Marshall came very close to being lynched

Thurgood Marshall's success as a civil rights lawyer also made him a target of racist whites. The danger was very real, since a big part of his job was traveling around the rural South, often alone, to represent people in court. Black families in the towns would risk their own lives to let him stay with them, and ThoughtCo. says he would move from one house to another to avoid detection, change cars mid-journey, and use disguises.

Marshall's closest brush with death came on November 18, 1946, in Columbia, Tennessee. He'd successfully secured acquittals from all-white juries for 24 out of 27 Black men who had been charged with various crimes including rioting and attempted murder following a large-scale clash with police. Thurgood Marshall was traveling with fellow Black NAACP lawyer Zephaniah Alexander Looby, and a white lawyer and journalist, when their car was stopped by police, who falsely accused Marshall of drunk driving. He was bundled into an unmarked car, supposedly headed to the police station, but Looby was suspicious and decided to follow.

His fears were proved right: the car left the road and headed towards the Duck River — a notorious lynching spot, now filled with a white mob. A prominent Nashville lawyer, Looby refused to leave without Marshall. The police, fearing the bad publicity, ultimately gave in and drove Marshall back to Columbia, and from there he and his companions drove to Nashville, just ahead of the mob.

Thurgood Marshall won the most famous Supreme Court case in history

Unless you're a lawyer or a law super-nerd, you can probably only name a handful of Supreme Court decisions. And we bet one of them is Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the unanimous 1954 landmark decision that found the concept of "separate but equal" that propped up segregation to be unconstitutional.

Brown was the culmination of the NAACP's strategic use of multiple lawsuits to attack segregation in education and beyond. The decision combined five separate cases brought by the NAACP against segregation in schools in five districts. Brown is Oliver Brown, the father of Linda Brown, who History says filed suit in 1951 when his daughter was denied admission to a white elementary school near their house in Topeka, Kansas.

In the Brown case, a lower court had found that although segregation negatively affected Black students, the facilities provided for them in this case were equal to those at the white schools, and therefore the Board of Education was not violating the "separate but equal" requirement. When arguing before the Supreme Court, Thurgood Marshall used sociological data to prove that attending segregated schools was damaging for Black students regardless of the facilities, because it instilled in them a feeling of inferiority. Therefore, laws based on "separate but equal" violated their rights under the Equals Rights Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court agreed, setting a new precedent that declared segregation inherently unconstitutional.

Thurgood Marshall didn't win every case

After becoming chief counsel of the NAACP in 1938, Thurgood Marshall focused most of his personal efforts on undermining segregation: but he also fought to save Black defendants who faced the death penalty. One such case that haunted him was that of the Groveland Four.

According to PBS, in 1949, four Black men were accused of raping a white woman in Lake County, Florida. Ernest Thomas was killed by a mob led by the county's notoriously racist sheriff, Willis McCall. The other men were jailed and beaten into confessing, although one man, Walter Irvin, never did. Despite evidence that proved the men weren't even in town when the alleged crime occurred, they were found guilty. Irvin and Sammy Shepherd were sentenced to death, while 16-year-old Charles Greenlee was sentenced to life in prison.

Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP appealed the case to the Supreme Court and won a retrial for Irvin and Shepherd (Greenlee didn't appeal.) But before it took place, McCall shot both men in the chest. Shepherd died, but Irvin survived that and a second gunshot. Marshall represented Irvin in his retrial in 1951, but the jury again found him guilty. His sentence was later commuted to life in prison. He was released in 1968, and died in 1970. Greenlee was paroled in 1962 and died in 2012. All four men were posthumously pardoned in 2019. While his successes outshone his losses in media reports, Marshall himself never forgot the Groveland Four.

Thurgood Marshall was not Martin Luther King, Jr.'s biggest fan

Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King both dedicated their lives — and risked them — to fight systemic racism in the US. But they had very different and sometimes conflicting ideas about how to go about it.

Marshall's most famous legal victory, Brown v. Board of Education, preceded King's first nationally recognized civil rights campaign, the Montgomery bus boycott, by about a year. But the truth of the Montgomery bus boycott is that the courageous actions of the Black protestors were given teeth by a Supreme Court decision argued by Marshall and other lawyers in the NAACP. The Washington Post says Marshall felt King took the credit for the legal team's hard work.

Throughout the Civil Rights Movement, Marshall disagreed with King's strategy of using non-violent demonstrations and marches to win civil rights, fearing that these would provoke a backlash and lead to attacks and riots against Black people. When he was named a Supreme Court Justice in 1967, Thurgood Marshall became part of the system King was trying to fight. As part of the establishment, he also disagreed with King's opposition to the Vietnam War. Even after King was assassinated, Marshall praised him as a leader and speaker, but said that his tactics didn't achieve tangible goals.

Thurgood Marshall had a complicated relationship with the FBI

Under J. Edgar Hoover's COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) the FBI spied on and sought to destroy civil rights organizations and Black radical groups. For example, the history of the Black Panthers includes stories of FBI informants and fake letters that exacerbated divisions between the party's leaders. Martin Luther King, Jr. was top of Hoover's list of targets, mainly because Hoover believed he had ties to Communists.

Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP were also wary of the Bureau's prying eyes, but they were more concerned about white supremacist terrorist groups like the KKK. As a member of the National Lawyers Guild, which represented civil rights groups and accused Communists, History says Marshall was suspected by the FBI of being a Communist sympathizer. Deciding that it was better to keep the FBI as an ally against more dangerous enemies, Marshall and other NAACP leaders strategically fed agents information about suspected Communists that had infiltrated the group.

When it came to King, Marshall's allegiances were torn. When Marshall found out King was being surveilled, he told him, but said the leader didn't care. When the FBI supposedly uncovered details about King's extramarital affairs, Marshall didn't believe the information but also defended Hoover. The Washington Post reported that Marshall said he'd never known Hoover to lie. In an interview published on Marshall's website, he said of Hoover, "I never thought he was [racist]. I still don't." But even Thurgood Marshall can't win that case in the court of public opinion.

Thurgood Marshall's second marriage was controversial

Thurgood Marshall's sense of humor and infinite charm made him a hit with women. In 1929, he met and married his first wife, Vivan Burey — known as Buster — when he was still in college and she had just graduated from the University of Pennsylvania.

It wasn't all smooth sailing. Marshall traveled a lot in his work with the NAACP and was accused of having affairs, and Burey's pregnancies ended in miscarriages. In late 1954, according to Thought Co., Marshall found out that Burey had been keeping a terminal cancer diagnosis from him, not wanting to distract him from the Brown case. She died in February 1955.

That December, Thurgood Marshall married his second wife, Cecilia Suyat, a secretary for the NAACP. They went on to have two children together. Some believed the couple had been seeing each other since before Burey's death, but it wasn't just the short time between Marshall's widowhood and his second marriage that raised eyebrows. In an echo of the life story of Frederick Douglass, some civil rights activists felt that Marshall was betraying Black women by marrying Suyat, a Filipino-American who grew up in Hawaii. But Marshall didn't care. In 2013, Suyat told the Southern Oral History Program that he said to her, "I'm marrying you. I'm not marrying the country, and they're not marrying me."

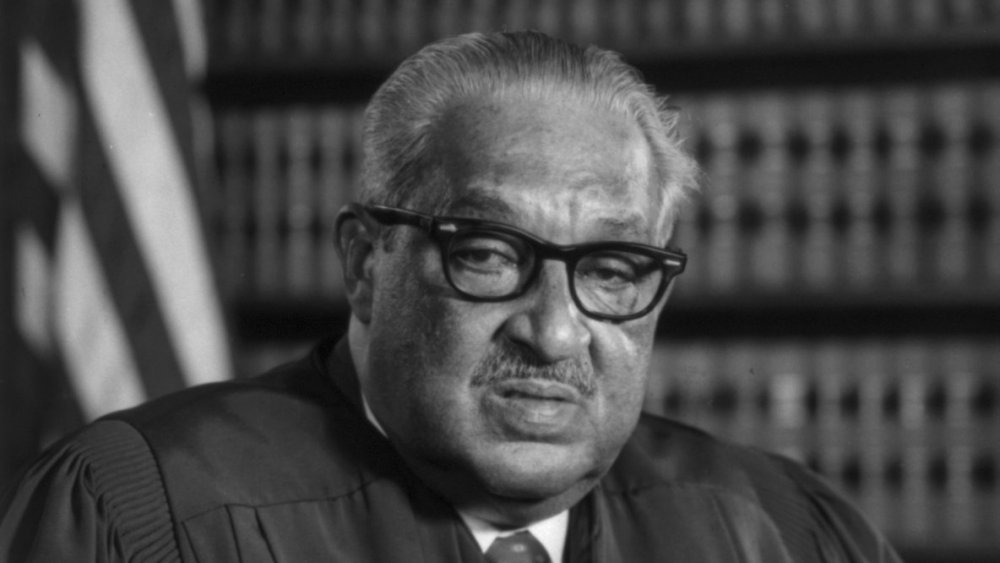

Thurgood Marshall was the Supreme Court's holdout liberal

Having spent over two decades confronting courtrooms with racial injustices, in 1961 Thurgood Marshall switched to the other side of the bench when President Kennedy appointed him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In 1965, President Johnson made him U.S. Solicitor General, which again meant arguing cases in front of the Supreme Court, this time on behalf of the federal government. The Independent says Marshall won 32 of 39 cases. In 1967, Marshall was confirmed as a Supreme Court Justice — the first Black person to serve on the highest court in the country.

Time records that throughout his tenure on the Supreme Court, Marshall fought to apply the rules of the Constitution to everyone in America, not just the white men its authors had in mind. As the Court became increasingly conservative, Marshall was often the lone dissenter, especially in cases relating to criminal justice. He didn't exactly fall in line with what we think of as liberal today. But he did aim to use his time on the Court to influence law in a way that conservatives bristled at.

Worried that he would be replaced with a conservative, Thurgood Marshall would tell his clerks, "If I die, prop me up and keep on voting." Ultimately, however, he retired from the Court in 1991, with plans to "sit on my rear-end." He died of heart failure two years later, on January 24, 1993.

That's St. Thurgood, by the way

Like all civil rights leaders, Thurgood Marshall was not a perfect person and he didn't always find himself on the prevailing side of history, at least not in his public declarations. (See, for example, his defense of J. Edgar Hoover, his criticisms of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s tactics, and his support of the Vietnam War.) However, he is still a hero among civil rights legislators, thanks to his determination to force the Constitution to live up to its promise to protect everyone equally — even people the Founding Fathers didn't regard as human.

Some people have taken this admiration one step further. In 2006, the Episcopal Diocese of Washington (D.C.), of which Thurgood Marshall was a member, made him a saint. This isn't the same as a Catholic saint: there's no need to prove miracles, and no one is worshiping him. As Alice MacArthur, a trustee of St. Augustine's Episcopal Church, explained to the Chicago Tribune, it's more about celebrating people who "have lived good lives." "Marshall risked his life for racial justice," she said.

His feast day is on May 17, the day the Brown v. Board of Education decision was handed down in 1954.