The True Story Of The Tuskegee Airmen

We often tell American history in terms of its heroics. We are drawn to movie-shaped pieces of the past, and the legendary Tuskegee Airmen provide that sort of story perfectly. As the first all-Black fighter group in the US Air Force, trained in Tuskegee, Alabama, their story is almost an archetype of a typically inspirational Hollywood plot and has been told on multiple occasions, most memorably in the 1995 movie The Tuskegee Airmen and in 2012 in the Lucasfilm production Red Tails.

But while these movies capture the spirit of the Tuskegee Airmen and their courageous accomplishments, our collective desire to mythologize our heroes and believe the Hollywood version of events means that we are quick to overlook the historical facts. But the fact is that the truth matters today more than ever. As the discourse of politics and societal debate becomes ever more bombastic and strident, it is important to remind ourselves of what hard-won societal change actually looks like.

So what really went on there? Let's separate the fact from the fiction, because even without the Hollywood treatment, the true story of the Tuskegee Airmen and their achievements is truly awe-inspiring.

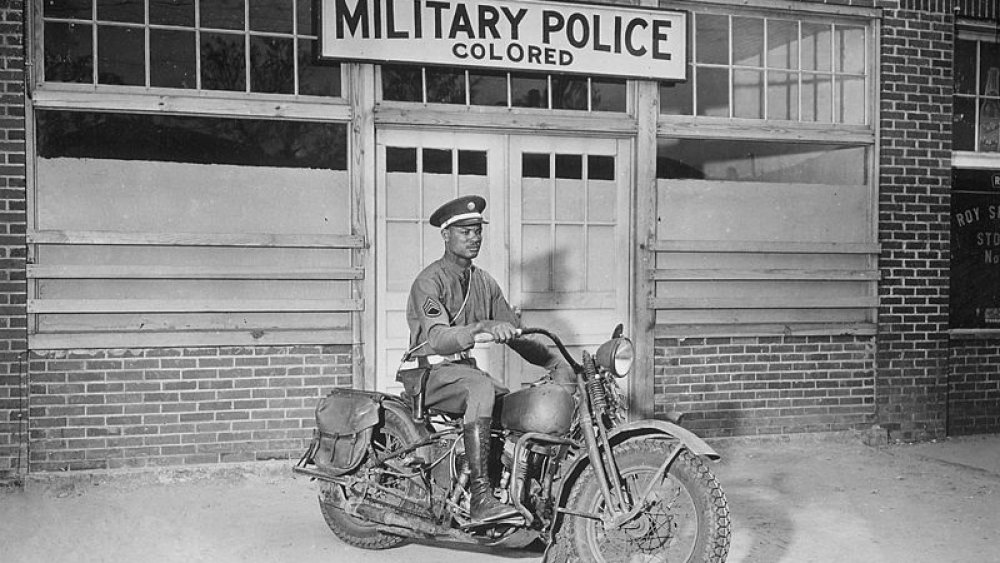

The US military was racist by design

The airplane was employed by the American military as early as 1909. However, while other countries such as France had Black gunners and pilots joining the war effort from 1914 onward, according to OZY, the United States Air Force remained segregated throughout World War I up until the 1940s. As Air Force historian Dr. Daniel Haulman points out, the reasons for this were written into US military policy, and they make for bleak reading today.

One memorandum, titled "The use of negro manpower in war," released in October 1925 by the US Army War College and preserved by the FDR Library today, demonstrates the continued systemic racism in the American military. Speaking of Black soldiers, it claimed, "Compared to the white man he is admittedly of inferior mentality. He is inherently weak in character." The memorandum recommends that Black personnel should be reserved for manual tasks and barred from those, such as aviation, that required intelligence and skill.

Set against such a backdrop, not to mention the ongoing racial segregation of civilian life in the US due to Jim Crow laws, the accomplishments of the Tuskegee Airmen when the project was finally undertaken in 1941 are even more striking.

Did Eleanor Roosevelt found the Tuskegee Airmen?

There's a charming story about the origins of the Tuskegee Airmen. The tale goes that First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was on a visit to the Tuskegee air base when she took a flight with C. Alfred "Chief" Anderson, who taught himself to fly as far back as 1929 and who is now considered the father of Black aviation. According to the story, the First Lady was impressed enough to return to President Roosevelt and convince him to establish the first all-Black flying squadron.

However, the training program for Black pilots had already been announced in January 1941, two months before the first lady's visit. Dr. Haulman states: "The President's wife visited Tuskegee, not to get a Black flying squadron started, but because the Black flying squadron had been started." The push to allow Black pilots in the American military had been a long and difficult battle, and the establishment of the Tuskegee Airmen followed years of lobbying by the NAACP and numerous press publications, according to Britannica.

So while the first lady was not directly responsible for the creation of the project, historians like Haulman have pointed out the importance of her enthusiastic support in changing the perception of Black pilots in the American media. Many news outlets carried the photograph of her and Anderson aboard his Piper J-3 Cub, and her words upon finishing the half-hour flight were widely reported: "Well, you can fly alright!"

The Tuskegee Airmen weren't all Black

This point sounds contentious, but really, it's a matter of definition. The story of the Tuskegee Airmen is popularly known to be that of the first Black pilots in the US Air Force, but in fact, the term itself means something broader — at least according to researcher and historian Theopolis W. Johnson, who was himself a pilot in the program: "That is ... anyone — man or woman, military or civilian, black or white — who served at Tuskegee Army Air Field or in any of the programs stemming from the 'Tuskegee Experience' between the years 1941 and 1949 is considered to be a documented original Tuskegee Airman (DOTA)."

Johnson has estimated that somewhere between 16,000 and 19,000 people fall into this category, and more than 14,000 of them have been given official DOTA status by Johnson himself. However, despite popular belief, the phrase "Tuskegee Airmen" was barely used during World War II.

The Tuskegee Airmen went by a different name

The phrase "Tuskegee Airmen" was, in fact, only coined in 1955, as the title of the book by Charles E. Francis which offered the first historical account of the project.

In actuality, during World War II, the pilots we now think of as the Tuskegee Airmen were known officially as the 332nd Fighter Group or, more commonly, by their nickname — the "Red Tails." They owe that name to the distinctive paintwork they applied to their P-51 Mustang airplanes to differentiate them from other fighter groups. However, they were by no means the only group to sport flashy designs, as noted by Haulman. The 325th Fighter Group, for example, had their tails painted with a black and yellow checkerboard design, while the P-51s of the 52nd Fighter Group were all painted bright yellow.

Being able to tell different groups apart was essential to aerial combat as well as the organization of units in the air, and the brightness of the tails served the useful function of helping pilots and gunners to quickly determine whether distant planes were friend or foe. However, the 332nd's all-red tail design seems to have stuck in the collective American imagination, and it even inspired the title of the 2012 movie from Lucasfilm.

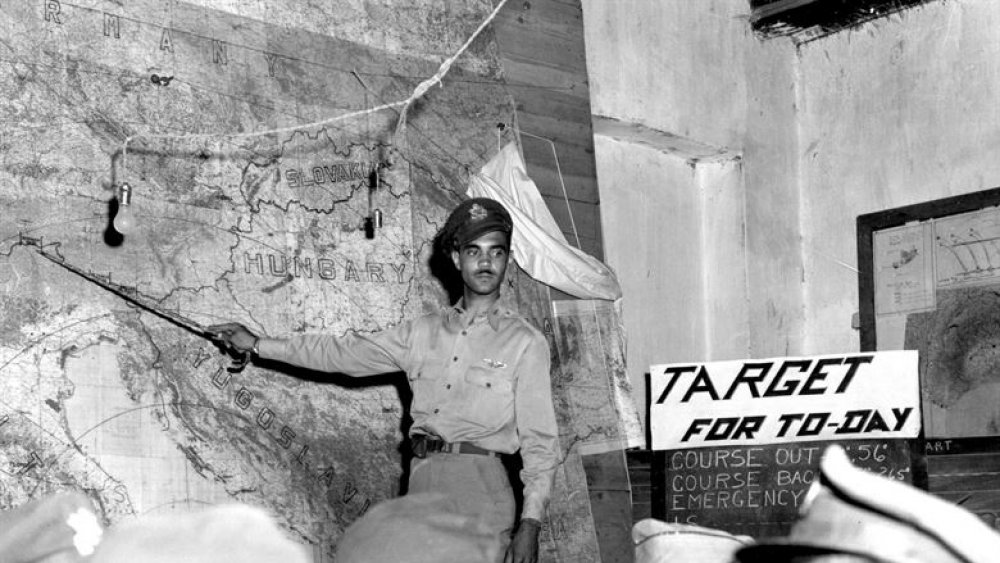

The Tuskegee Airmen served as escorts and dogfighters

Tuskegee-trained Black pilots had engaged in action in the Allies' Operation Corkscrew in Italy in 1943 as members of the 99th Fighter Squadron, for which they were awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation. According to historian Alexander M. Bielakowski, it was in this engagement that 1st Lieutenant Charles B. Hall became the first Black pilot to shoot down an enemy airplane.

However, it was in February 1944 that the 332nd Fighter Group was first sent overseas, and with it, the legend of the Red Tails was born. Under Commander Benjamin O. Davis Jr., who had also led the 99th Squadron for a time, the 332nd grew to become trusted escorts to fleets of bombers as they headed to their strategic targets of attack all over Western Europe. "Our mission of escort was really the prime mission to carry out successfully and this we did. The 332nd became known as the best escort operator in the 15th Air Force," said Davis.

The task demanded skill, discipline, and acute perception and judgment from the pilots, gunners, and their commander, who had to ensure that the fighter planes maintained a tight formation around the bombers they were defending while timing perfectly maneuvers with which they might evade, chase away, or destroy approaching enemy fighters bent on preventing the bombs from dropping. During World War II, the Red Tails conducted 1,578 missions, 15,533 combat sorties, and downed a total of 112 enemy planes, according to Theopolis W. Johnson.

Benjamin Davis challenged racism against Black officers

While the dexterity, discipline, and quick judgment of the pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group were instrumental in successfully challenging the long-running systematic racism of the US military, Colonel Davis himself became a key figure in changing the perception of Black officers and the ability of Black military personnel in positions of command. Consider that the program at Tuskegee to train Black pilots was originally described as an "experiment," as Johnson notes. That should give you a sense of the attitudes that the Red Tails had to contend with.

On June 9, 1944, the 332nd Fighter Group, along with the 301st and 302nd, escorted a huge number of bombers from the 15th Air Force to their targets in Munich, Germany. A total of 17 bombers were lost on the mission — but only two of the bombers downed had been accompanied by the Red Tails, according to Haulman.

The 15th awarded Davis the Distinguished Flying Cross, stating that he "so skillfully disposed his squadrons that in spite of the large number of enemy fighters, the bomber formation suffered only a few losses." Davis' strategic skill is seen today as a vital vanguard for Black excellence within the US military in the years that followed. He went on to become the US Air Force's first Black four-star general, per Britannica. His father, Benjamin O. Davis Sr., had performed a similar feat by becoming the first Black brigadier general in the US Army.

Prejudice dogged the Tuskegee Airmen throughout the War

Unfortunately, the racism against Black pilots as seen in the Hollywood depictions of their stories is far from fictional. It is worth remembering that the Tuskegee Airmen were still segregated from the rest of the US Air Force, despite, as Britannica claims, the NAACP opposing such a practice.

Despite their proficiency in the sky, white officers continued to disparage the performance of the Red Tails. "Colonel William Momyer of the 33rd Fighter Group opposed the continued combat role of the 99th Fighter Squadron when it was attached to his group," claims Haulman. These Black pilots were criticized fiercely by Momyer and others, although by as early as 1944, reports of their actions in their early missions proved them to be as capable and effective as their white counterparts.

The continuing segregation of civilian life at home in the US also served as a precedent for the treatment of Black pilots in the military, which led to grave consequences for those who fought for equal treatment at the military bases that were essentially their homes during World War II. Haulman gives the example of Colonel Robert Selway, who commanded the 477th Bombardment Group based at Freeman Field, who "attempted to enforce segregated officers' clubs at that base, and had many of the Tuskegee Airmen arrested for opposing his policy."

Comparing the Tuskegee Airmen to other groups is difficult

How well did the Red Tails really do? Despite wanting to make sports-like comparisons between them and other Air Force groups, analyzing them this way is unfair due to the high number of variables we have to consider. Fighter groups are often judged by the number of enemy planes they shoot down — hence the name. If this is the case, then the Tuskegee Airmen shot down considerably fewer planes than many of the other American fighter groups serving in World War II. However, as Colonel Davis noted, this was not their primary mission — their job was to get bombers safely to their enemy targets.

Haulman has unpacked several of the myths around the Red Tails' contested military records. Indeed, it is optimistic to expect that the accounts of what happened in the heat of war are ever going to be entirely correct. But between those who claim that the Red Tails never lost a single bomber and the belief that the missions they were given were purposefully assigned to them to limit their potential, some semblance of truth might be found. The fact is that 27 American bombers were lost under the protection of those pilots we consider the Tuskegee Airmen. However, across all fighter groups serving during World War II, the average number of bombers lost was, according to Haulman, 46 — almost twice as many. The Red Tails' defensive prowess perhaps explains their lower "hit rate."

The Tuskegee Airmen never had an ace

The bravery of the Tuskegee Airmen is perhaps best demonstrated by the story of Lieutenant Lee Archer, one of the group's finest and most fearless pilots. According to the History Channel, on October 12, 1944, he downed three German ME 109s in the skies above southern Hungary. Archer, as the wingman for Captain Wendell Pruitt, was returning to base in Italy from an envoy mission when the Red Tails met an enemy formation of Nazi fighters and chose to engage them head-on. Archer swiftly dispatched two enemy fighters tailing Pruitt before chasing a third Nazi to his doom despite taking a hit to his own left wing.

The History Channel states that Archer's actions that day brought his total kill count to five, but as with much of the legend of the Tuskegee Airmen, the actual story is still up for debate. No one questions that Lee Archer heroically downed three German fighter planes in a single day — however, Archer did not achieve the title of "ace," given to those pilots who shoot five or more planes down during service, according to both Johnson and Haulman, who place his count at four. As fitting as the story of the first Tuskegee ace would have been, it's not quite true.

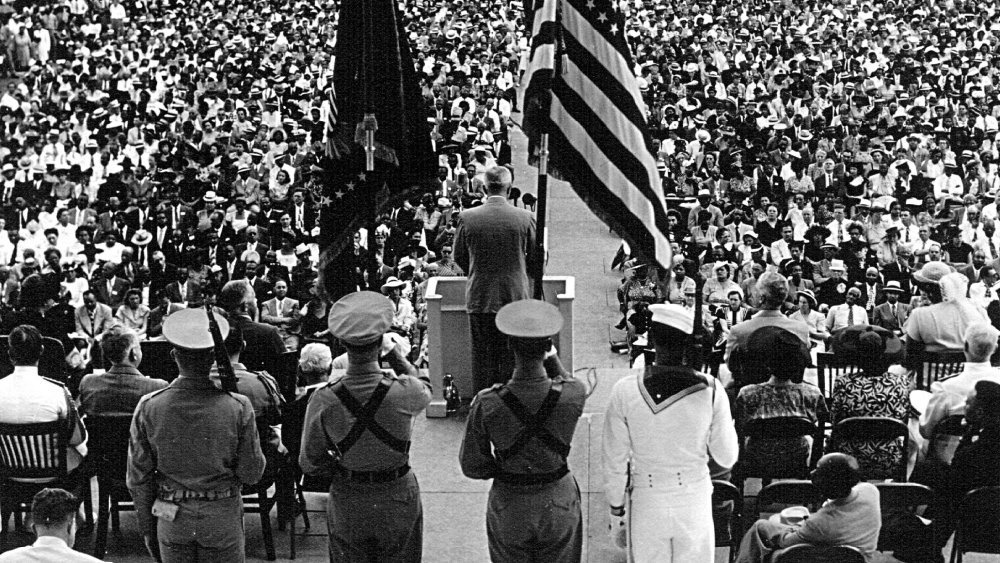

At war's end, the Tuskegee Airmen returned to a segregated America

Like Jesse Owens returning from the Olympics over a decade earlier, the distinguished pilots of the 332nd returned to the continued enactment of Jim Crow laws and a segregated society. Their combined achievements should have seen them welcomed back to the United States as national heroes. In addition to their impressive bomber escort record, the pilots today known as the Tuskegee Airmen received, according to Johnson, three Presidential Unit Citations, 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses, eight Purple Hearts, 25 Bronze Stars, and 1031 Air Medals. Four Soldier Medals were awarded to Captain Woodrow W. Crockett, the Red Star of Yugoslavia was awarded to 1st Lieutenant William W. Green Jr, and both the Legion of Merit and Silver Star were awarded to Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr.

However, segregation continued to be in effect in parts of the United States until well into the 1960s. As the organizers of the CAF Rise Above education program explain: "German prisoners of war were treated better than Black Americans. It would be decades before their war efforts were acknowledged or even widely known, and it could be said that even today many people do not know about the remarkable achievements of the Tuskegee Airmen. Misinformation, or lack of any factual information at all, is rampant."

The military was finally desegregated under Harry Truman

The Tuskegee Airmen showed commitment, determination, and courage to succeed against the odds and help to end segregation within the US military system, the same qualities that are needed to bring about change today. "They fought successfully against two enemies at the same time," says Daniel Haulman: "Nazi Germany, and racism among their own countrymen."

On July 26, 1948, around the time the Tuskegee "experiment," or "experience," as Theopolis W. Johnson calls it, was coming to an end, President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order to create the President's Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services, through which the government committed to making the US military racially integrated. Even then, there was ongoing resistance within the military itself.

Today, the achievement of equality within both the military and civilian spheres of American life is still ongoing, but the example set by heroes such as the Tuskegee Airmen shows that change is possible even in the darkest periods of American history.