The German Farmer Who Was Executed For Being A Werewolf

First off, it's important to note that the modern justice system is far from perfect. Innocent citizens are convicted unjustly, and the guilty are handed punishments disproportionate to their crimes. With that said, it is so important to hang onto the little victories ... like the fact that people don't still torture, behead, and cremate folks suspected of being werewolves.

For example, look at Peter Stubbe. The details of his life are thin on the ground, but in the late 1580s, Stubbe was living that agricultural life on a farm in Germany. His home was just outside of Bedburg, a town whose presumed slogan of "Don't Let The Bedburgs Bite" probably came under scrutiny when a series of decidedly werewolfy murders began to take place. According to Modern Farmer, the culprit, a shadowy and insatiable cryptid, was described as "strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like unto brands of fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharp and cruel teeth, a huge body and mighty paws." As the mutilated remains of missing women and children began to show up in fields and on the sides of roads, the locals took to traveling in large groups, sending out hunting parties to make like the villagers in a Disney movie and kill the beast.

Years went by. The monster wasn't caught. Then, in 1589, a team of trackers encircled something in a field. Something that they were sure was the Werewolf of Bedburg. Something suspiciously similar in shape and personality to Peter Stubbe.

Here, wolfy wolf

There's been some debate over the years regarding the actions which led to Stubbe's confession. Some accounts state that the farmer was tortured until he confessed to being a horrible lupine monstrosity, sated only by the blood of the innocent. Others believe that he was only threatened with torture. In either case, Peter Stubbe found himself at the wrong end of a 16th century Jack Bauer tête-à-tête and admitted to his heinous misdeeds.

In a colorfully written pamphlet from the following year, now online via the University of Pittsburgh, the method of Stubbe's unholy transformation was revealed. In his confession, he recounted making a deal with the devil at the tender age of twelve years old. In exchange for his eternal soul, Stubbe was granted a belt which would allow him to take the form of a great and indestructible wolf. Questions like "where's the belt now?" and "why aren't you using it to Hulk Smash your way out of here?" seemed to fall into the "problems for later" category. There was a werewolf to burn.

For his acts of debauchery, which reportedly included the seduction of a goodly Christian woman and the consumption of his own child, born of an incestuous relationship with his daughter, Stubbe was sentenced to a gruesome demise.

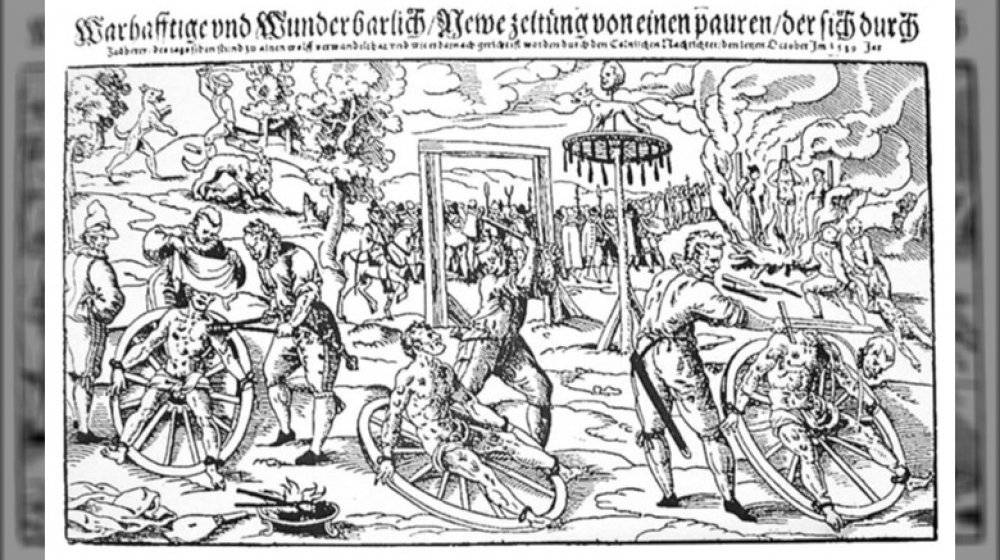

The Germans really knew how to get their money's worth out of an execution

According to the University of Pittsburgh's descriptions of the execution, the Werewolf of Bedburg was sentenced "first to have his body laid on a wheel, and with red hot burning pincers in ten several places to have the flesh pulled off from the bones, after that, his legs and arms to be broken with a wooden ax or hatchet, afterward to have his head struck from his body, then to have his carcass burned to ashes." Which, you know. That'll do it. The punishment was carried out on Halloween, 1589. Not wanting to waste a perfectly good people fire, and perhaps thinking that safe was better than sorry when it comes to ungodly lycanthropic abominations, the town also burned Stubbe's daughter and girlfriend. The belt was never found. The devil never showed up to testify for the defense.

Historians still debate the actual actions of Peter Stubbe, pondering whether he really was a serial killer. Maybe his instability led to clinical lycanthropy, a recognized psychiatric delusion involving the belief that one turns into a literal werewolf? At the time, though, the supernatural was an easy scapegoat, and perhaps Stubbe bought into it as much as anyone.

Or maybe a good time was hard to find in 1589, people are kind of the worst, and pulling a guy's skin off meant having something to talk about at dinner. Who knows.