The Messed Up History Of Mount Rushmore

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The iconic heads of four United States presidents loom over the Black Hills in South Dakota. It's a popular place for millions of people to visit every year. A family traveling through the plains might stop to check it out and take a photograph that'll be immortalized over the fireplace, or wherever people typically keep those types of photos. For many white Americans, Mount Rushmore is as fine a sight to see as any. To many Native Americans, not so much.

To the Great Sioux Nation, Mount Rushmore is the symbol of a dark, treacherous past full of stolen land, broken treaties, and a fierce fight to keep their traditional way of life in the face of an invading government. Each presidential face that was carved into the sacred Black Hills comes with its own sordid past. Each symbolizes unique slights committed toward Native peoples. Most Americans have little clue about the very real and messed up story of Mount Rushmore's past or how it has affected the indigenous people of the area into the present, and knowing the truth could forever change the way they look at the towering monument. But maybe that's a good thing.

The Black Hills were promised to the Sioux and Arapaho tribes

Before colonial Europeans showed up and decided that the lands of North America were theirs for some reason, indigenous tribes freely roamed, hunted, and shared the resources of the Earth through all of the future United States. The colonists weren't happy with sharing, so they started to take instead, pushing the native inhabitants from their homes and murdering most of them in the process. After a whole lot of fighting, the United States started to make treaties with the indigenous people that granted them portions of the land and some autonomy in the form of reservations. Of course, the US is a champion treaty-breaker, so most of these reservations were subject to change anytime the colonial government decided.

The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, according to Smithsonian Magazine, granted 60 million acres of land to the Sioux and Arapaho tribes in South Dakota while designating the Black Hills as open territory for any native tribe. The Black Hills were sacred to several different indigenous groups, so it made sense. The 1868 treaty is still being disputed today. The Sioux want the US government to honor their treaty since within 20 years of its signing, the United States had managed to steal most of the original land back. The Sioux were left with just 12.7 million acres under the 1887 General Allotment Act, according to Britannica.

Gold was discovered in the Black Hills

The first break in the treaty happened after gold was discovered in the Black Hills. General George Custer led an expedition to find the precious metal in the summer of 1874 specifically in those sacred hills. Since the gold-hunting expedition was meant to be in Native American territory, it draws a pretty specific conclusion: the US government was looking to break their treaty with the Sioux.

Custer's expedition was successful, according to Britannica, and this success led to an influx of white colonizers who were trying to strike a fortune the following year. Smithsonian Magazine puts the number of white miners at around 800, while Britannica estimates it was in the thousands. The Sioux weren't happy about this, as no one would be, and skirmishes broke out in the area. Prospectors and settlers were under attack, so the government passed a decree that forced the native people to stay on their reservation or be punished with military might.

Eventually, the skirmishes broke became war, and the Sioux got Custer back at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The US government responded by redrawing the boundaries originally set by the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The new boundaries "legally" granted the Black Hills to the US.

The Supreme Court granted the Sioux millions in reparations

It took about 100 years, but the United States finally admitted they'd done something wrong when they stole the Black Hills way back in 1877. In 1979, the US Supreme Court granted the Sioux reparations in the amount of $17.5 million, according to the Northern Plains Reservation Aid. The messed up thing about it was that they didn't apologize for taking the land. They simply decided it was wrong of them to forcefully take it and not pay anything for it. According to the Treaty of Fort Laramie, the government isn't allowed to buy Sioux land without the adult males of the tribe confirming the sale with a 75-percent majority vote.

Now, that $17.5 million the Sioux were awarded was in reference to the time the land was taken and has increased at five-percent interest since then. So, in 1980, that came out to a little over $100 million, but they never cashed the check. According to PBS, that number has grown further over the years, bringing it to over $1 billion in 2011. The check still wasn't cashed. "But that's so much money!" you might say. Yeah, maybe, but the Sioux just want their land back. It was, after all, illegally taken in the first place. The Sioux tribe's official stance is that the land was never for sale.

Six Grandfathers, a sacred mountain

The mountain that became Mount Rushmore had no name that the colonists knew of, or so it's said. In reality, the Sioux people called the giant, holy hunk of stone "Six Grandfathers." There seem to be conflicting accounts of where the Sioux name came from. According to Black Hills Pioneer, the name was in reference to the four directions plus earth and sky. The book The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings says the name came from a vision had by Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux holy man, and references five ancestors and himself as the sixth grandfather.

The name "Rushmore" came about from a joke. It wasn't actually supposed to be named that. According to Cabinet Magazine, a lawyer by the name of Charles Rushmore had visited the mountain and asked his guide what its name was. The guide replied that the mountain had no name, so they'd just call it Mount Rushmore from then on. And, unfortunately, they did. Well, not the native peoples of the area. They still tend to refer to it by its traditional (proper) name.

Rushmore began to receive calls once the monument was publicly announced. People wanted to know what fantastical things he must have done to find his name on such an epic landmark. Out of what we can only assume was embarrassment, he donated $5,000 to the project.

Mount Rushmore's Native American counterpart is also controversial

Because the Black Hills are sacred to the Sioux, defacing the Six Grandfathers is one of the many reasons why Mount Rushmore is a backhanded slight toward them. But, Mount Rushmore is getting a Lakota counterpart. That should appease everyone, right? No, it won't, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Since defacing sacred mountains is considered a no-no, you can see where some indigenous people would be less than happy to see another one get carved up, even if the carving is of a Native hero.

The monument in question is a towering depiction of the Lakota leader Crazy Horse. When we say "towering," we mean it — the monument is set to stand at 563 feet tall. That's over nine times taller than the heads of Mount Rushmore. The sculpture was designed by Korczak Ziolkowski, one of the sculptors who worked on Mount Rushmore, at the behest of Lakota chief Henry Standing Bear. The carving actually started back in 1948, but it's nowhere near finished. The end product is meant to show Crazy Horse mounted in all his glory. As of now, only an 87-foot-tall head stands for viewing. A mix of funding issues and environmental conditions are drawing out the construction, but it should be finished someday.

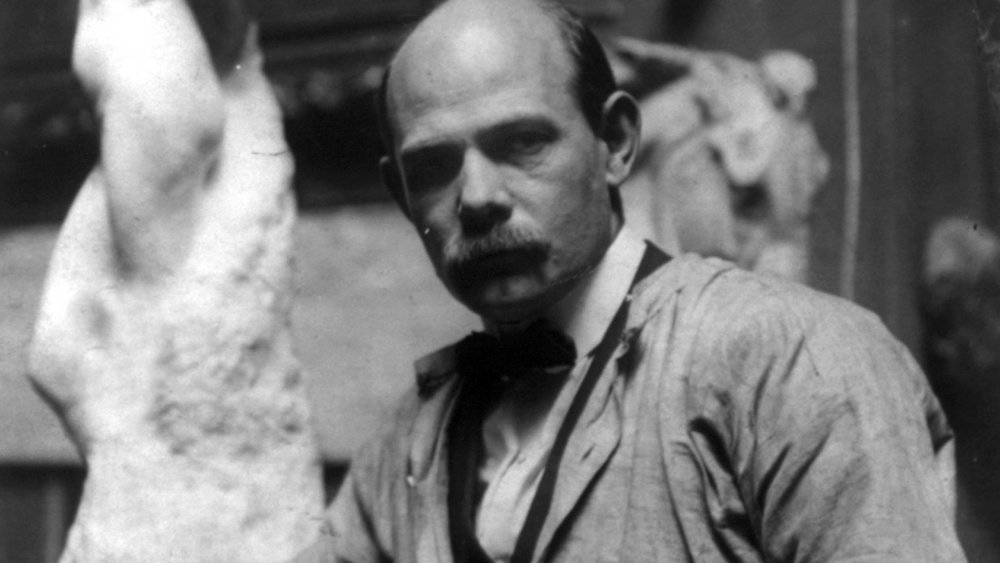

The guy who carved Mount Rushmore was a member of the KKK

The further into Mount Rushmore's history one digs, the more messed it up it becomes. The presidential monument seems to have been created just to insult the Native Americans who once inhabited the lands without restriction, or at the very least, it was poorly thought out. Unfortunately, Mount Rushmore's designer's ties to the Ku Klux Klan don't support the latter.

Gutzon Borglum worked on another famous monument before working on Mount Rushmore: Stone Mountain. If you don't know about the Stone Mountain carving, it's the largest Confederate memorial in the country. While working on Stone Mountain, Borglum made friends with the local Grand Dragon. According to History Collection, Borglum would become a member of the Klan on Stone Mountain and remain a member for the rest of his life.

Though it's argued that Borglum was only affiliated with the Klan to further his career, willing association with a white supremacist organization kind of makes anyone a bad dude. Other sources, such as Vice, argue that Borglum chose each of the presidents based on their role in "manifest destiny," which both makes sense when you look at each's history and is absolutely disgusting.

George "Town Destroyer" Washington

The first president holds the leftmost spot on the Mount Rushmore memorial carving, the center of the US one-dollar bill, and a controversial spot in the hearts of the indigenous people of America. It's said that Borglum picked George Washington for getting the American expansion started. Washington wasn't exactly anti-Native American, but he was definitely pro-white people.

The United States' number-one revolutionary general was known to trade with different Native American tribes and fight alongside others. He spent much of the French and Indian War interacting with various Native peoples and building respect for the Native warriors. In fact, according to George Washington's Mount Vernon, Washington would use many of the tactics he learned from the indigenous people while commanding revolutionary forces against the British. But Washington wasn't all sunshine and rainbows toward Native Americans. Only when it suited him.

The Iroquois had a name for Washington, and it had nothing to do with him being a founding father. They called him "Town Destroyer," you know, because he destroyed their towns. The Iroquois and the newly American Americans had been having conflicts for some time, which is expected when you start colonizing a land that already has people on it. Well, Washington ordered the total destruction of Iroquois settlements through upstate New York, according to US News & World Report. What a great guy to put on Mount Rushmore, right?

Thomas Jefferson set the groundwork for Native Amercian removal

We might as well explain why every president on Mount Rushmore was a messed up choice. We'll go left to right to make it easier to follow. Thomas Jefferson is known for many roles throughout early American history, from the man who drafted the Declaration of Independence to the guy who fathered several illegitimate children with a woman he kept as a slave. One thing he isn't as well-known for, but definitely did, is setting the groundwork for removing Native Americans.

Jefferson might have been the third president, but he was the first president to put forth broad policies to remove the indigenous people from the newly fought-for and purchased lands. He pushed further and further west, according to Indian Country Today, believing that the already inhabited lands belonged to white Americans because, um, magic, or something. Expanding American territories with the Louisiana Purchase is one of the reasons Bolgrum chose him to be on the Rushmore monument.

The third US president was talking about removing Native Americans before the US was even founded. He was known to find the indigenous people fascinating at different times of his life but ultimately decided that getting rid of them and obtaining their land was in the best interest of national security. He even devised a dubious plan to force the natives to sell their lands by driving them into debt via trading posts.

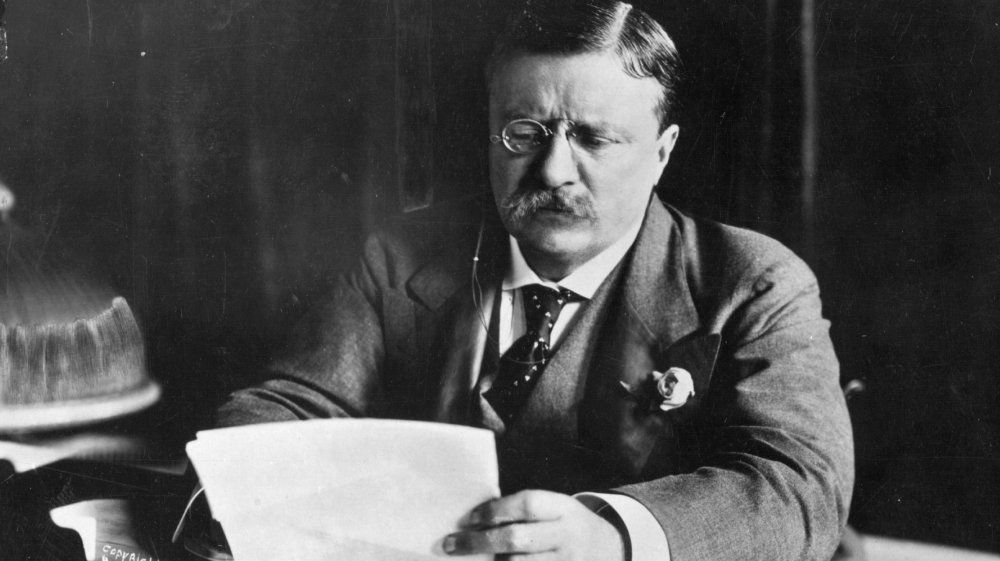

Theodore Roosevelt downright hated Native Americans

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt, 26th president of the United States, said some of the worst things ever said by a president. While giving a lecture in New York in 1886, Roosevelt talked about his "western view" of Native Americans where he described them as "fiendishly cruel" and claimed they were always attacking those poor settlers ... who stole their land. Roosevelt said that even "the most vicious cowboy" was nothing compared to a Native American. The most famous line from the particular speech is this one: "I don't go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every ten are, and I shouldn't like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth."

Yeah, that guy's head is displayed second to the right on Mount Rushmore, which resides on lands sacred to and promised to Native Americans. Pretty messed up, right? But, dear old Teddy wasn't all talk. According to Indian Country Today, Roosevelt systematically worked to displace Native Americans. He seized 230 million acres of land and placed it under protection in the form of national parks. He also outspokenly supported the General Allotment Act as a force to assimilate indigenous Americans, calling it "a mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass."

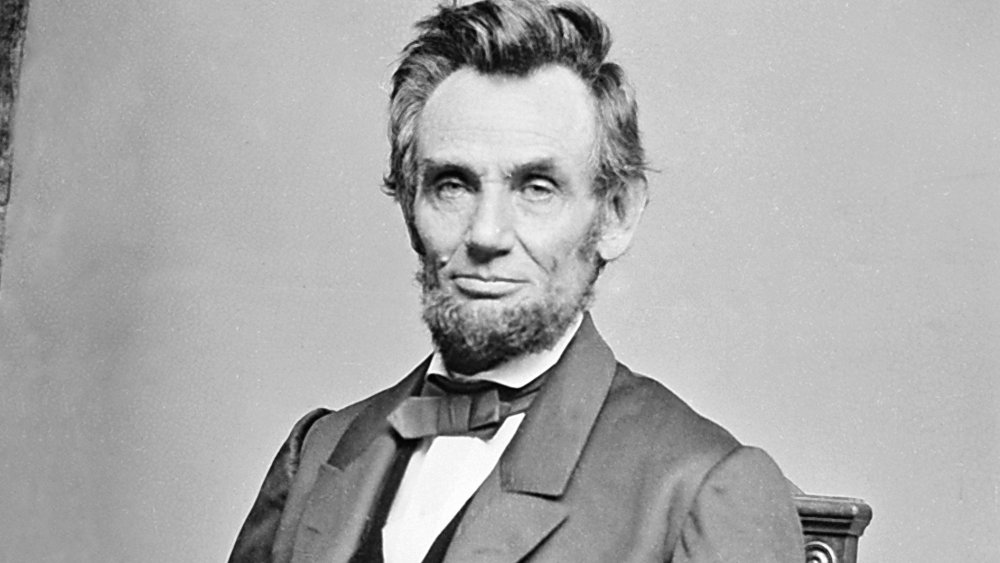

Abraham Lincoln hanged 38 Dakota men

We all know that Abraham Lincoln did great things for the United States. He was the commander-in-chief during the Civil War and issued the Emancipation Proclamation that freed people previously enslaved. To many Native Americans, though, Lincoln was far from the hero he's made out to be in the textbooks.

For starters, Lincoln issued the Homestead Act in 1862 that allowed any citizen to claim land as their own, provided that they never took up arms against the Union. The act took the land out from under the indigenous people who'd inhabited it for centuries. Within a few months, the Pacific Railway Act was put in place, granting land and loans to the building of a transcontinental railroad. With both acts, not only was land distributed to an invading government, but the traditional ways of the indigenous Americans would forever be disrupted by western culture.

More atrocities were committed directly that cost the indigenous people their lives, such as removing the Navajo and Apache from New Mexico via a 450-mile march. According to Washington Monthly magazine, around 2,000 members of these tribes would die before a treaty was established. Under Lincoln's command, 303 Dakota men were sentenced to death for the outbreak of the Dakota War. Lincoln did pardon most of the men but still ordered 38 to be hanged on December 26, 1862. Yet, most of his face is now on a sacred Sioux mountain.

Mount Rushmore brought millions to white-owned businesses while the reservation suffered

As you can imagine, 60-foot-tall presidential faces drew in a slew of tourism basically from the start of Mount Rushmore's carving. With tourism comes cash. The local economy was, and still is, flooded with millions of dollars every year, but the Native people of the land don't see it. From the first chisel-strike, white-owned businesses flocked to the area to set up shop, capitalizing on land that was promised to the Sioux, and according to Cabinet Magazine, that was the original purpose behind the monument.

Businesses prospered, which isn't bad in and of itself. The problem is that white-owned businesses profited off stolen Sioux land, while the Pine Ridge reservation, home to the Oglala Lakota, was suffering. Poverty was rampant then and continues to be today. The economic situation at Pine Ridge is one of the factors that led to the occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973, which you'd expect in an area that once had an unemployment rate of 89 percent. This isn't uncommon in reservations, though, and there are several institutional factors that help to keep reservations in poverty.

To put things into perspective, Mount Rushmore drew in 2.4 million visitors in 2017, injecting $177 million into the local economy. The average yearly income on the Pine Ridge reservation is around $9,000 per person.

The Committee for the Return of the Black Hills

The fight for the Black Hills, including the Six Grandfathers, continues today. It's part of the reason the Sioux have never cashed that big check the government gave them. They never intended to sell the hills, and they'd very much like them back. They were promised them with the Treaty of Fort Laramie, after all.

The Supreme Court totally agreed that the Black Hills were illegally seized from the Sioux. Of course, that wasn't until 1979. The court also decided that giving the tribe back its lands would be totally impossible because of time or some other lame excuse. Shortly after (1982), one representative of each tribe that made up the Great Sioux Nation got together to form the Committee for the Return of the Black Hills. They fought for a decade trying to get the Black Hills and part of the originally promised lands back under Sioux ownership, but multiple attempts were blocked at different governmental levels, according to Cabinet Magazine.

South Dakota representatives fought the Sioux's rightful claims tooth and nail. Senator Tom Daschle of South Dakota formed the Open Hills Association in 1990 specifically to fight any attempts by the Sioux to regain the Black Hills, according to Native American Roots.